The Age of Self-Discovery was a milestone for the English poetry and novel that opened the doors for the intellectual creativity and innovation of 20th-century writers.

Literature during the Victorian Era identified itself with the ethical values of that society. The superficial optimism and bigotry of a self-righteous attitude forged a kind of literature that was condescending and emotionally wanting.

Apart from the few exceptions like Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, most of the production of that period lacked the emotional intensity or the daring experimentation of writers belonging to other periods.

The tide began to change during the last two decades of Victoria’s reign, when some writers sought a newer and fresher approach to literature.

The end of the century brought about writers like Oscar Wilde, who broke away from Victorian tradition through aesthetic and decadent models, or like Hardy and Conrad, who were close to naturalistic and existential themes.

It was, however, the First World War which triggered in man an awareness to see life as an abyss of incessant self-discovery. The trauma which the Great War had caused revealed new feelings and shattered traditional values and ideals.

The Poetry

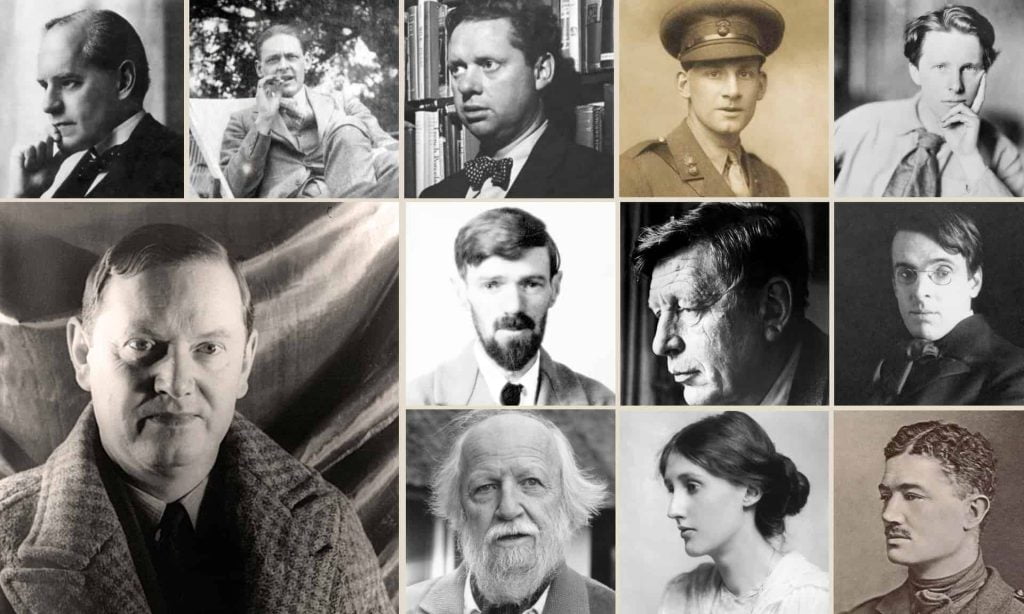

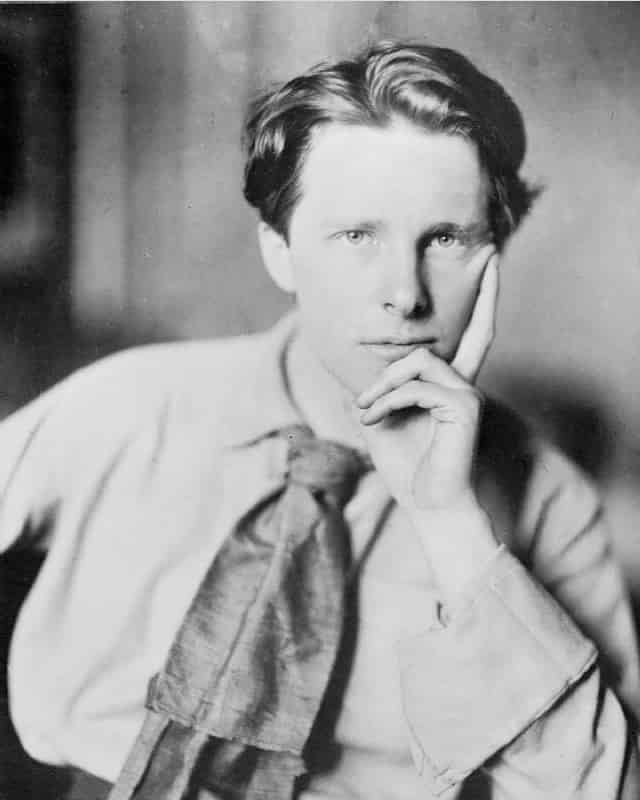

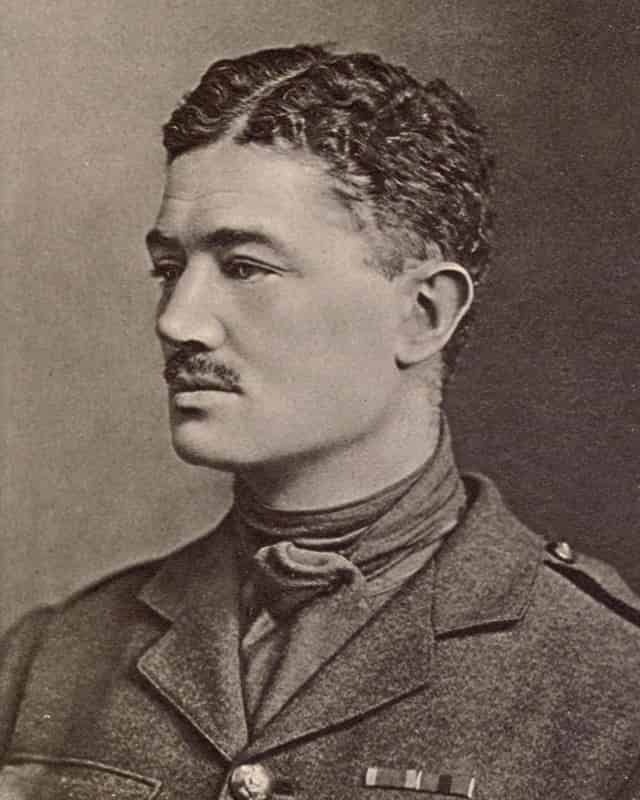

The direct fruits of the age of self-discovery were the war poets like Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke and Siegfried Sassoon. They expressed the disillusionment of those thousands of young soldiers who went to war with courage and heroism in their hearts and who ended up realising how insane and futile the war actually was.

In 1915 Rupert Brooke died, in active service, of blood poisoning on his way to the Dardanelles at the young age of 28. His poems and his extremely handsome good looks instantly made him the typical romantic hero of that generation. His Poem The Soldier seemed to have been prophetic:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England

Another young poet, Julian Grenfell, had also written a prophetic poem which was published in The Times the same day he was killed in battle in the dreaded trenches in France. His poem Into Battle cried:

If this be the last song you shall sing,

Sing well, for you may not sing another.

Other soldier war poets who were killed were Edward Thomas, Isaac Rosenberg and Wilfred Owen. War was the essence of their poetry. Owen wrote:

“My subject is war and the pity of war… The poetry is the pity”

Thomas wrote about the horrors of the war through his memories of the tiny English country station Adlestrop, on a hot summer’s afternoon. Rosenberg had published Night and Day in 1912 and had written a type of poetry which could be termed as confessional. He was killed in France in 1918. Wilfred Owen, who is probably the most well-known and widely read war poet, was also killed in 1918. He wrote the memorable lines:

“My friend, you would not tell with high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori”.

The most famous war poet who survived the Great War was Siegfried Sassoon. He lived to the venerable age of 81 During World War One he was known as Mad Jack because of his daring solitary expeditions. He was the first poet to express his disapproval and disgust of the horrors of the war.

He wrote of “the unreturning army that was youth” and of “the simple soldier boy” who shot his brains out. This type of writing really shocked the English patriots of his society.

Sassoon’s best poems which expressed his feelings against the war were collected in Counter Attack and Satirical Poems. Later in life Sassoon could never forget the tragedy of the First World War, and wrote nostalgic autobiographical works which were very touching.

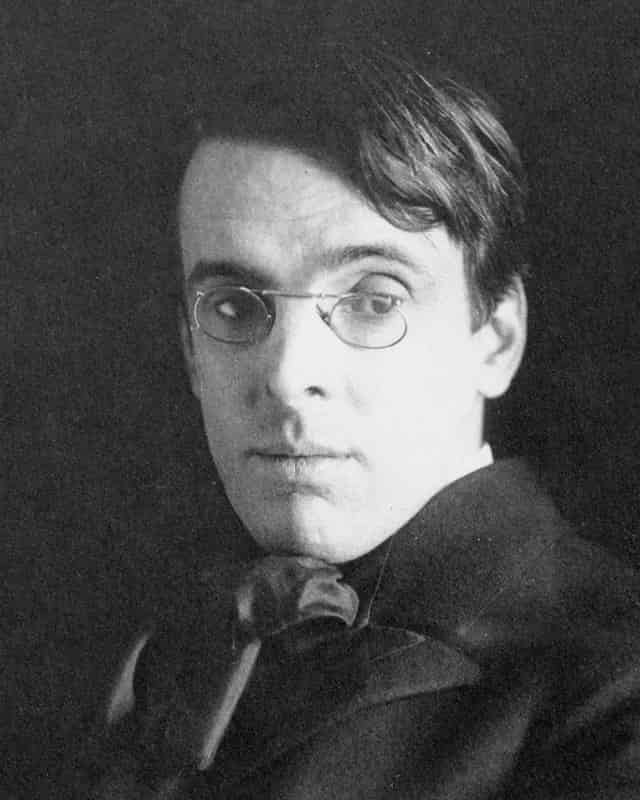

Generally, however, post-Victorian poetry stemmed mainly from two major traditions: the symbolists of the late 19th century and the metaphysical school of the late 16th century.

The symbolists

On the one hand, the former school of poetry, whose main founder was Eitienne Stephane Mallarme, expressed its poetic inspiration through intuitive and suggestive expression.

The poets represented their ideas through symbols associating images, feelings and emotions with specifically invoked elements. One of the main poets belonging to this group was Dylan Thomas.

Read more: Towards the Third Millennium: UK literature after the Second World War

Thomas’ work was complex and difficult to understand. It was not, however, intellectually complex. Its difficulty lay in the elaborate and obscure imagery and the allusive style. Dylan Thomas was considered to be a new romantic as his themes were generally based on romantic notions of love, nature and humanity. His poetic structure was always musical and mellifluous.

Another poet who was influenced by the French symbolist movement was William Butler Yeats. His poetry owed a great deal to Mallarme, Baudelaire and Verlaine. Yeats, who has become one of the leading 20th-century poets, used a great deal of obscure imagery and symbols.

His work revolved around theories, philosophies and mysticism. His mystical side developed in the light of his studies on William Blake, whose works he admired greatly.

The metaphysical school

On the other hand, the latter school of poetry, whose main founder was the 16th century poet John Donne, created a poetry of terse, almost scientific analysis.

Read more: Your Full Guide to John Donne’s Life, Career & Poems

Metaphysical poetry was intellectually difficult and very down to earth in its creative expression. The precise and scientific imagery of this literary school went against the romantic vision of life. The analytical and anti-romantic conceits used by the Metaphysical Poets were paradoxical comparisons which equated a potentially romantic idea, emotion or situation to something down to earth, factual and precise.

The main exponent of this school in the 20th century was undoubtedly Thomas Sterns Eliot, whose rebellion against 19th century romanticism and Victorian convention was the essence of his poetic output.

Read more: Your guide to T.S Eliot poems

He was the neo-metaphysical par excellence. Examples of the anti-romantic similes are his comparisons between “the evening” to “a patient etherized upon a table” found in The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, or between the typical human emotion of anxiety to “a taxi” waiting impatiently, found in The Waste Land.

Eliot’s reaction to the contrasting years of bloodshed and aloofness was more existential, focusing on the lack of values and meaninglessness of life.

He managed to capture the feelings of futility, senselessness and degradation of his contemporary society. He looked at the past by highlighting the grandeur of its simple values, ideals and artistic creativity. Through the exaltation of that grandeur he managed to focus on the aridity and dullness of his society.

Another poet whose experimental creativity helped revitalise the art of poetry was Wystan Hugh Auden. He, too, felt strongly about the emptiness of his society but his work had a more socio-political slant, focusing on themes like the Spanish Civil War and Nazism.

Auden was considered to be one of the Progressive Poets of the 1930s and his fame was secured from his very first collection published by Eliot’s publisher, Faber & Faber, in 1930 and simply entitled Poems.

The Age of Self-Discovery was really quite a turning point for poetry. The art of writing poetry found fertile ground for innovation and experimentation in that post-Victorian society, which had had enough of convention and tradition. The devastation of the Great War and the declining values of an increasingly sterile society did the rest.

The Novel

Like poetry, the novel was also in need of new dynamic energy by the end of the 19th century. Since Defoe, Richardson or Fielding, the development of the novel had been steady, but not particularly adventurous in the innovation of style and structure. Tradition and convention were the basis of the Victorian novels which, although having fresh and interesting elements regarding content, were always standard in the presentation of their stories.

The Age of Self-Discovery instilled a creative urge within the novelists to discover not only their existential position in a life, emptied of sound ethical values and tradition, and marred by the ruthless massacre of a futile and senseless war, but also to discover new means of self-expression. The early 20th century development of the novel, which was linked to this revolt against tradition, is often termed ‘modernism’.

Modernism and the stream-of-consciousness

The two giants who really shook the pillars of convention in the world of the novel were James Joyce (1882-1941) and Virginia Woolf (1882-1941). Their tools of innovation were the Stream-of-consciousness and the interior monologue.

The use of the stream-of-consciousness technique is by far the literary device which added new dynamic freshness and vigour to a genre which was long due for renovation. This technique actually belonged to the world of psychology.

The psychologist William James, brother of the American author Henry James, had used the term stream-of-consciousness to describe the haphazard gushing of emotions, memories, thoughts and perceptions which take place within us without following a logical or chronological order. William James explained this in The Principles of Psychology (1890). His theory was that a confused succession of memories and feelings could be suddenly brought on in one’s mind by external stimuli like music, perfumes or even just a banal action.

The distant music of a familiar song could, for example, remind you of an incident which had happened years earlier while listening to the same song. In your mind those memories, and the emotions linked to them, mingle with the present situation. In your mind, past, present, mixed emotions and perceptions simultaneously unravel.

This kind of experience is psychologically inherent within man and therefore the most daring experimental writers found that it should be transferred to the world of literature.

Basic external realism, they believed, did not really capture the true essence of life.

Structural events in a novel were seen to be limiting, while the turmoil and haphazard development of the mind’s random flow of thoughts and emotions were, on the contrary, seen to be the true complex reality of man and his world.

At first, the novels written with this technique were very difficult to understand and seemed to make no sense. However, once the reader grasped the objectives of the author, the picture as a whole became coherent. A perfect example of the brilliant use of this literary device is Ulysses, written by James Joyce.

This is the story of a man’s day in Dublin. It is one of the first great mythopoetic novels of the 20th century. The first pages of the book will confuse the reader, who may find the novel extremely difficult to understand, but once the reader appreciates the fact that the book does not focus on external plots and intrigue, but rather on the exploration of the intimate psyche of the characters, the value of the novel becomes apparent.

The work provides a masterful glimpse into the stormy enigma of the human mind. It reveals psychological reality and paves the way to a greater understanding of life in general.

Joyce also exploited the interior monologue, which is the pouring out of a character’s thoughts and feelings, usually expressed by the character himself/herself. Sometimes, however, the interior monologue is recounted by a narrator in the past tense. Whichever way it may be, this device is a splendid way of opening a door into the mysteries of the character’s intimate soul and mind.

The works of Virginia Woolf added a personal touch to the stream-of-consciousness and interior monologue with the introduction of the “she/he thought”.

Read more: Unlocked and Unbolted – Virginia Woolf’s Life and Works

Woolf completely rejected the traditional concept of the novel. Her belief was that a novel should “record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall (…) trace the pattern, however disconnected and incoherent in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness.”

She believed that novels should not “preach doctrines, sing songs, or celebrate the glories of the British Empire.” Her novels most certainly did not. They explored the inner labyrinths of the mind and soul of her characters with profound lyrical intensity mixed with a virtual scientific interpretation.

Her brilliant Mrs.Dalloway, for example, described one day in the inner world of Clarissa Dalloway. It is a deep analysis of three major characters who reveal their innermost perceptions and feelings through Woolf’s acute sense of experimentation with the characters’ train of thoughts. Her lyrical musicality and rhythm is characteristic of her work and blends well with her stream-of-consciousness technique.

The best example of this union is found in The Waves, which is a very poetic development of the lives of a group of friends from childhood to adult life.

Virginia Woolf formed a group called the Bloomsbury Group, named after the residential London district where the friends and writers used to meet in 1906. All shared similar artistic and intellectual interests. A member of this group was Edward Morgan Forster (1879- 1970) who wrote the memorable novels Howards End (1910) Maurice (1913-14) and A Passage to India (1924).

Read more: Edward Morgan Forster: Life and works

These novels portrayed vivid pictures of the well-to-do English society, focusing on the depth and psychological development of the characters.

Other authors of that period who studied the upper-class English society were John Galsworthy (1867-1933), who wrote The Forsythe Saga (1906/21), and Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966), whose most famous works are Decline and Fall (1928) and Brideshead Revisited (1949).

Evelyn Waugh’s insight into man’s psychology was quite astounding. Sebastian in Brideshead Revisited has mesmerised many readers. The young aristocrat’s soul-searching quest for self-fulfilment and understanding was a perfect picture not only of the type of society he belonged to but also of human psychology in general.

Another author who delved into human psychology was William Somerset Maugham (1874-1965). His type of experimentation lay in his studies of the complexities of human sexuality. One of his best novels, Of Human Bondage (1915), is a painful attempt to come to terms with his own bisexuality. The clubfoot of Philip, the protagonist, is a symbol of how Maugham viewed his own ‘crippled’ sexuality.

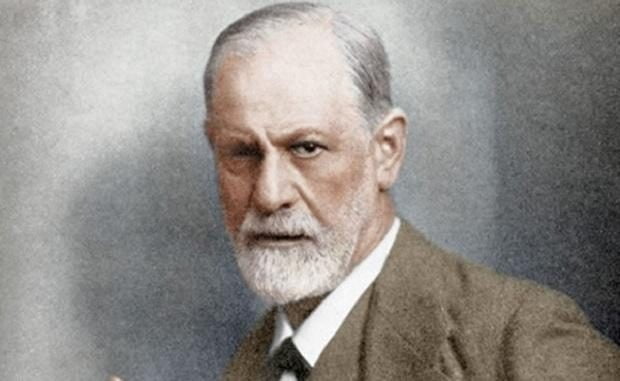

Freudianism in literature

During this period some novelists were also picking up their inspiration from Sigmund Freud, who gave dreams and sexuality a new important position in a psychologically based vision of life. Freud didn’t think much of the surrealists, but their leader André Breton got his inspiration from him.

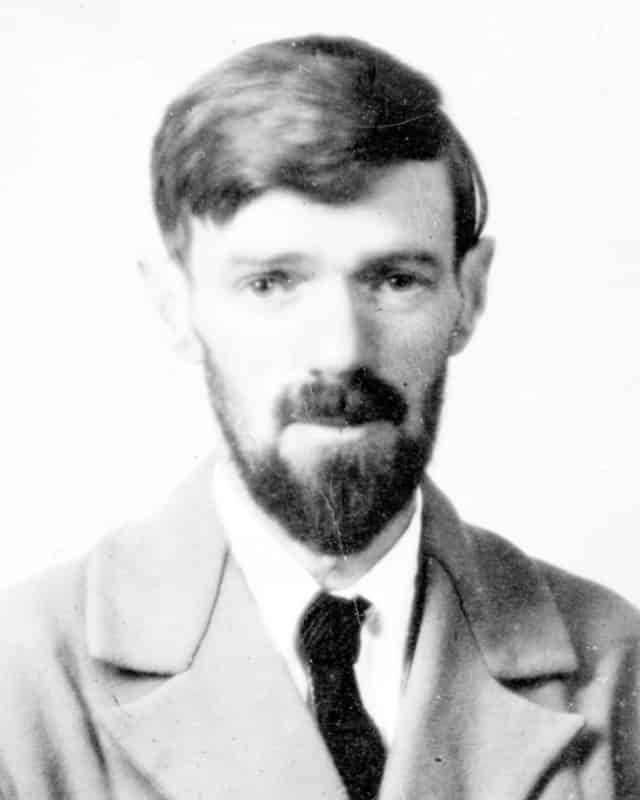

Together with Freud’s view on the world of dreams came his view on traditional morality. His works on psychoanalysis and his studies on sex inspired, in particular, David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930) who believed in instinct rather than logic.

Read more: David Herbert Lawrence – The Freudian who hated industrialisation

His books, like Lady Chatterley’s Lover, shocked society. Many of his books were censored and rejected as obscene. Lawrence believed that sex between man and woman was ruined by the intellectualisation and logical analysis of it. This type of “sex in the head” as he put it, interfered with instinct and therefore with ultimate happiness.

The dystopian and utopian

Later on in the century, from the 1930s onwards, came the dystopian novel. The dystopian novel, that is the anti-utopian novel, highlighted the dangers which could be awaiting man in the future with a frigid and perfect society void of any human values.

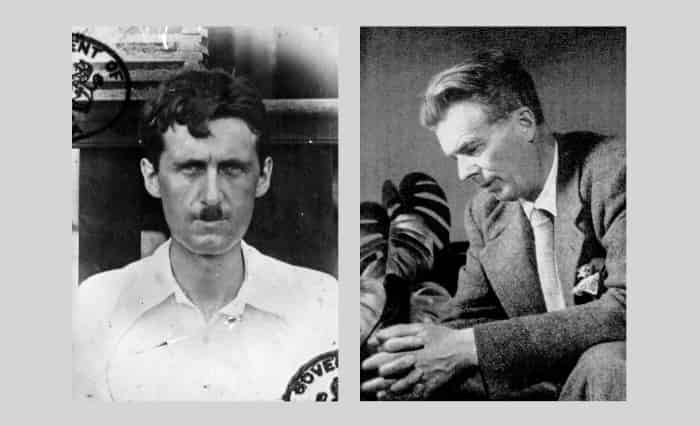

The word utopia, in Greek meaning nowhere land, refers to a book written by Sir Thomas More (1478-1535), in which the author presents a perfect society. The book written in 1516 describes an ideal world in which everything is perfect. The dystopia, in Greek meaning bad place, highlights the negative and dangerous qualities of a would-be perfect society. The two main writers who chose this genre were Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) and George Orwell (1903-1950).

Brave New World, written by the Aldous Huxley, was obviously a clear example of dystopia. The scientifically perfect society of the Brave New World reflected the dangers of its cold and empty human values.

George Orwell, on the other hand, expressed the dystopia by focusing on totalitarian regimes and their despotic society. Nineteen Eighty-Four is a perfect example of this type of totalitarian world, in which Big Brother kept a vigilant watch over everybody. Individuality in this world became a crime and people were seen as mechanised dummies:

His head was thrown back a little, and because of the angle at which he was sitting, his spectacles caught the light and presented to Winston two blank discs instead of eyes. What was slightly horrible, was that from the steam of sound that poured out of his mouth it was almost impossible to distinguish a single word. (Nineteen Eighty-Four).

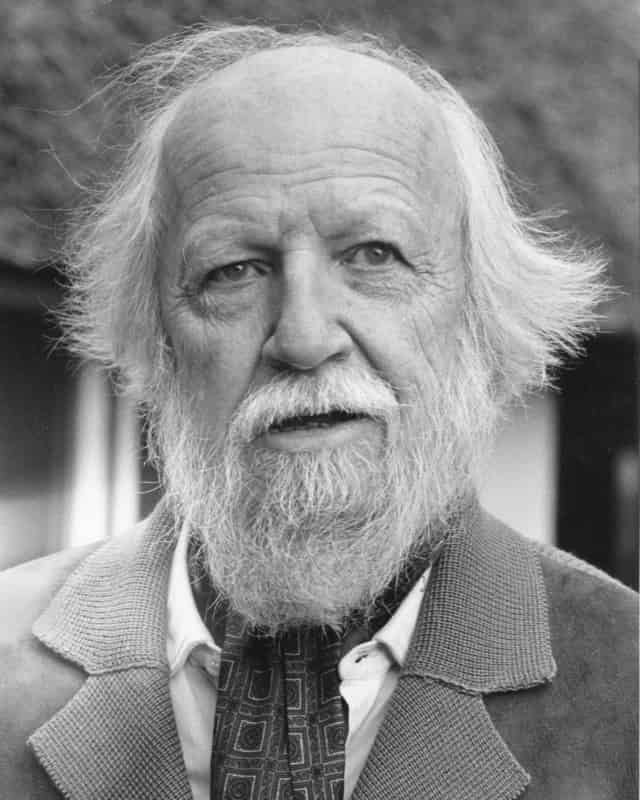

The dystopian novel was also present after the Second World War in the 1950s with William Golding’s, The Lord of the Flies.

All in all, it can safely be said that the Age of Self-Discovery was a milestone for the English novel. The new techniques and experimentation established a new relationship with literature.

The doors, which had long been ajar, were finally opened for the intellectual creativity and innovation of the 20th century writers.

In the next issue we shall be surveying the development of drama during this period.