Virginia Woolf and her tumultuous psychological hardships should be considered an essential cornerstone of modernist fiction.

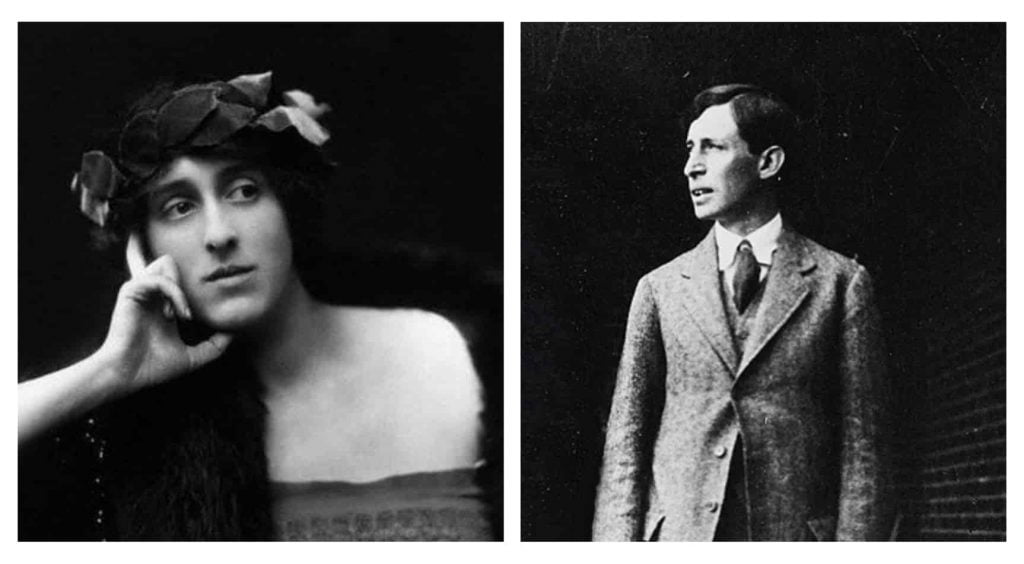

Early life

Virginia Woolf was born in London on the 25th of January 1882. Her father, Leslie Stephen, was an eminent Victorian critic and man of letters. He was the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. He was married twice. His first wife was William Thackeray’s daughter Minny.

After her death, he married Virginia’s mother, Julia Duckworth, who was also from an illustrious family. She was a widow and had three children from her first marriage. One of these children, George Duckworth, sexually harassed Virginia later on in life, devastating her psychological stability.

…there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind

Virginia had two brothers, Thoby and Adrian, and one sister Vanessa. Their childhood together was extremely happy until the first tragedy in Virginia’s life. In 1895 her dearly beloved mother, Julia, died suddenly. This tragic loss was to trigger her first nervous breakdown. She was helped by her half-sister Stella (Julia’s daughter from her first marriage), who attempted to take Julia’s place as a mother.

Unfortunately, the tragedy was repeated only two years later when Stella also died suddenly, causing Virginia to fall back into depression. In the meantime, she found no help from her half-brother who had already started tormenting her with his sexual advances.

At this point, Virginia was on the verge of a total breakdown. There was a metamorphosis in her character. She became sullen and introverted, her proverbial joie de vivre was lost forever. Then came the final blow. Her brother Thoby died of typhoid fever in 1906. There was no turning back for Virginia’s injured mental well-being.

The Bloomsbury Group

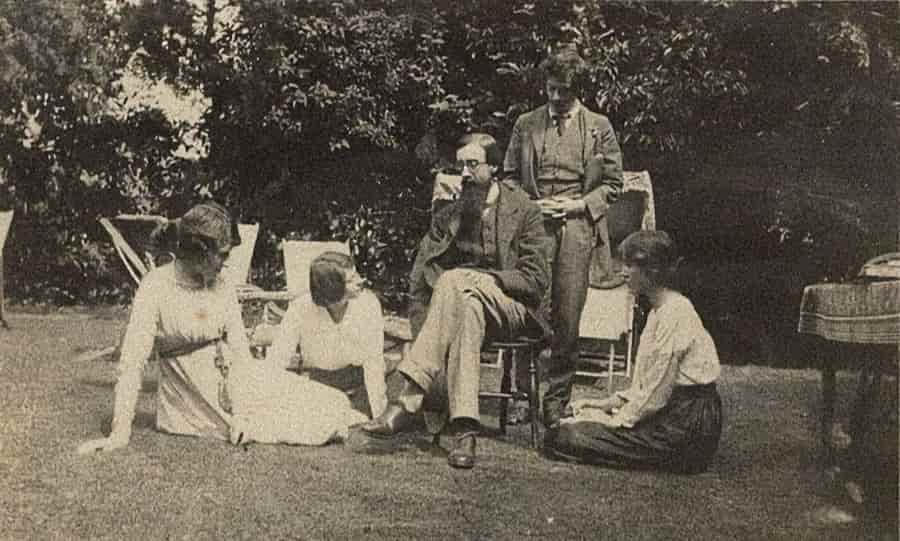

Virginia found great comfort in her sister Vanessa, whom she loved very much, and also in their new home in Bloomsbury. This home had become a fulcrum for intellectuals and artists who visited regularly. It was the beginning of the Bloomsbury Group, which was made up of outstanding personalities who broke away from Victorian convention in their quest for new styles in art and literature, and for a new nonconformist way of life.

Vanessa married the art critic Clive Bell, who had been a good friend of Thoby’s, and both helped promote the Bloomsbury circle. Bell wrote about the group: “they shared a taste for discussion in pursuit of truth and a contempt for conventional ways of thinking and feeling, contempt for conventional morals if you will”.

The group promoted modern French post-Impressionist painting, which outraged the straight-laced Edwardian public, still tied to the Victorian tradition of conservative ideas. The English painter who slowly helped change this narrow-minded attitude was Roger Fry, another Bloomsbury member.

Through the Bloomsbury Group, Virginia met her husband Leonard Woolf, who, along with her sister Vanessa, became her greatest lifelong friend. Virginia and Leonard had problems with their sexual relationship, which was scarred by Virginia’s psychological problems, caused by her half-brother’s sexual harassment in the past. However, their love went beyond mere physical attraction. She once told Leonard: “I feel no physical attraction to you [….] and yet caring for me as you do almost overwhelms me”.

Her mental health progressively deteriorated, but her husband stood by her through thick and thin. Virginia was becoming very well-known as a writer. By 1930 she had become very successful and had earned a lot of money from her books. Leonard was also a writer of note and wrote about the Bloomsbury Group and about his life with Virginia.

In this period Virginia also befriended Vita Sackville-West, who was a renowned homosexual. Their friendship was intense and emotional, but Virginia still stood by her husband and never left him. Sackville-West was jealous of Leonard and said about Virginia that she liked “people better through the brain than the heart”.

The beginning of the Second World War depressed both Virginia and Leonard. They both feared a possible victory of Hitler. Virginia’s depression, however, was far more serious. She could not bear the thought of going totally mad.

The one experience I shall never describe…

On the 28th of March 1941 while they were in their country home, Monk’s House by the river Ouze, she wrote to her sister and to her husband. To Vanessa she wrote: “I have gone too far this time to come back again. I am certain now that I am going mad again […] and I know I shan’t get over it”. To Leonard she wrote: “I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer. I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been”.

She then walked to the river and putting a large stone in her coat pocket, she jumped into the water to her death, which was to be, as she once said: “the one experience I shall never describe”.

Literary Career

Virginia Woolf proved to be a very competent writer by 1912, when she worked as a critic for the Times Literary Supplement. With her husband, in 1917, she established the Hogarth Press which published her works, and those of many other anti-traditionalist writers. Woolf wrote nine novels in all and also a great number of other works like short stories, essays, letters and diaries.

She wrote her first two novels in 1915 and in 1919. Both these novels, The Voyage Out and Night and Day, were plot-oriented and rather traditional in style. Her first attempt at experimental writing was made with Jacob’s Room which she wrote in 1922. The story is not revealed chronologically; it is understood through the reminiscences of the characters. These memories unfold the life of a young man and his experiences until his death in war.

1925 can be considered to be the turning point of Woolf’s style which, with Mrs Dalloway, marks her choice for the stream of consciousness, already experimented by Joyce in Ulysses and by Proust in A la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Naturally, the book was accepted with some resistance and a lot of curiosity.

“Virginia Woolf has taken fiction into new waters in Mrs Dalloway, using an experimental technique of directly recording consciousness, that ‘semi-transparent envelope surrounding us’, as she has called it”.

Chronicle, Dec. 1925

To the Lighthouse (1927)

In 1927 Woolf wrote To the Lighthouse. The first part of the book describes one day in the life of a large family and of other characters on holiday in the Hebrides. Mr and Mrs Ramsay, the main characters, mirror Virginia Woolf’s own parents and the relaxed atmosphere of her childhood prior to her mother‘s death. One of Mr and Mrs Ramsay’s eight children, James, wants to go to the nearby lighthouse, however, due to the bad weather he cannot.

In the second part of the book, there is a time-lapse. We learn that two of the Ramsay children had died earlier. Mrs Ramsay also died suddenly, leaving an unbearable void. The atmosphere is totally different. The third part recounts the events of one day, but ten years later. The family return to the house in the Hebrides with some friends. Mrs Ramsay’s spirit pervades their emotions of nostalgia and James can finally go to the lighthouse which remains steadfast in the unravelling of their lives.

Orlando: A Biography (1928)

One of Woolf’s most original books is Orlando: A Biography written in 1928. The book is about Orlando, who lives across time and sex gender. He lives through different centuries, changing from man to woman. The story focuses on the universal qualities of the human being who, according to Woolf, should be considered for the existential qualities which transcend time and gender. The novel is also an enigmatic way of recounting her relationship with her female friend Vita Sackville-West. Orlando was an instant success selling over 6000 copies.

The Waves (1931)

The Waves, which she wrote in 1931, was also successful, even though it initially encountered tough criticism. This novel was more like prose-poetry, depicting a very sad picture of existence through a life-span of a group of friends and their introspections and mental associations.

The Years (1937)

The last novel which was published in her lifetime was The Years (1937) in which she abandoned total experimentation for a more traditional approach. Between the Acts was published just after her death in 1941, and with this novel Woolf again blended prose with poetry, focusing on the performance of a pageant.

Virginia Woolf also wrote innumerable short stories, essays and letters not to mention her extensive diary, written between 1915 up to the day she died. The diary was published posthumously in 1953 as A Writer’s Diary.

Style and Themes

“How to impose significance on the flux?

In a sense, the whole subject of Virginia Woolf’s novels is this very question: when one thinks in the abstract of a typical Virginia Woolf character one seems to see a tiny figure on tiptoe eagerly grasping a butterfly-net alert to snare the significant, the transcending moment as it flies.”

This description of the works of Virginia Woolf, written by Walter Allen in The English Novel (Pelican, 1975), is a perfect portrayal of the essence of Woolf’s artistic achievement. The characters she created always overcame the general obscurity of the haphazard train of events, perceptions and emotions, by becoming essential pieces of a mosaic, which eventually disclosed the essence and inherent meaning of the whole picture.

Woolf managed to reach that “meaning” not by a traditional development of the novel, which needed a well-constructed plot and a conventional character study, but rather by recording, as she herself wrote in 1919: “the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall” and by tracing “the pattern, however disconnected and incoherent in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness”.

She was, in this respect, utterly against conventional realism, which she called materialism. She was in controversy with Arnold Bennet, who was the writer of Anna of the Five Towns (1902) and of The Old Wive’s Tale (1908). Bennet was closer to the naturalists like Zola, and also to the realism of Balzac and Turgenev.

Two typical characteristics of Virginia Woolf are her use of the stream-of-consciousness technique and the interior monologue. However, she never reached the literary heights of James Joyce, whose works were intellectually more intricate and wrought.

Arnold Kettle wrote in The Pelican Guide to English Literature (Pelican, 1973): “Joyce is a far bigger figure than Virginia Woolf – his work bristles with an intellectual and moral toughness which hers lacks”. Woolf’s characters are also not as universal as those of Joyce. They all belong to a specific upper class and basically follow very similar psychological standards. They are, nonetheless, unique and exceptional creations. Through their disconnected and incoherent development Woolf majestically manages to capture the essence of their existence.

Virginia Woolf’s prose style is vibrantly figurative and symbolic. Her symbols, like the sun, the night or the sea, are never banal. They are intelligently manoeuvred and woven within her use of the stream-of-consciousness. The language she uses is powerful in its imagery and in its technical adaptation to the mood by blending different patterns, such as short uneven sentences into longer descriptive ones.

The works of Virginia Woolf and her tumultuous psychological hardships should be considered together as an essential corner-stone of modernist fiction.