People and nations may disagree, they may commit crimes, but these antagonisms can be resolved in countless ways. Why war?

“When I see all my kingsmen, Krishna, who have come here on this field of battle, life goes from my limbs and they sink, and my mouth is sear and dry; a trembling overcomes my body, and my hair shudders in horror. My great bow, Gandiva, falls from my hands and the skin of my flesh is burning; I am no longer able to stand, because my mind is whirling and wondering. And I see forebodings of evil, Krishna. I cannot foresee any glory if I kill my own kinsmen in the sacrifice of battle. Because I have no wish for victory, Krishna, nor for kingdom, nor for its pleasures. How can we want a kingdom, Govinda, or its pleasures or even life, when those for whom we want a kingdom and its pleasures, and the joys of life are here in this field of battle, giving up their wealth and their life?” (Translation by Juan Mascaró)

Pathetic excuses

These are the words of Prince Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita to the god Krishna, who was standing by his side as the opposing armies prepared to engage in battle. On my first reading of the Gita, many years ago, I imagined that Krishna would reply something to the effect of: “Well done, Arjuna! War is a nasty business, leave it well alone…”

Instead, his words trigger a mild scolding followed by the profound philosophy the Gita is famous for. Indeed, as Putin’s barbarous war on Ukraine once again demonstrates, we have to stand up for our rights and combat evil whenever it threatens us. This self-defence is a duty as well as a right. However, war is a complicated affair and things are not always clear cut as one nation trying to dominate, exploit or occupy another country or part of it, particularly with regards to civil wars which tend to be more idealistic. The reason why men chose to engage in wars (and yes, it usually was men) were manifold: murder, theft, abductions, invasions, insults, greed, religion, power-lust…

The most crucial issue, however, is not what provokes the conflict, or how to resolve it, but how the conflict is conducted. People and nations may disagree, people and nations may commit crimes, but these antagonisms can be resolved in countless ways. Why war?

If my neighbour brazenly repositioned the garden posts to misappropriate some of my land and I killed him for it, I would end up in prison or worse. If, however, one country goes to war against another for a border dispute, which results in thousands of deaths: that is fine.

The problem is that it is not fine; not by any standard. In the dawn of civilization, life was cheap. People would kill people as a means to an end and those who chose to mind their own business and focus on creating happy communities were often the victims of the more predatory kind of human being. Even then, however, there probably existed an awareness that a line had been crossed and intensive purification rights were common amongst primitive societies for those who had shed blood in war.

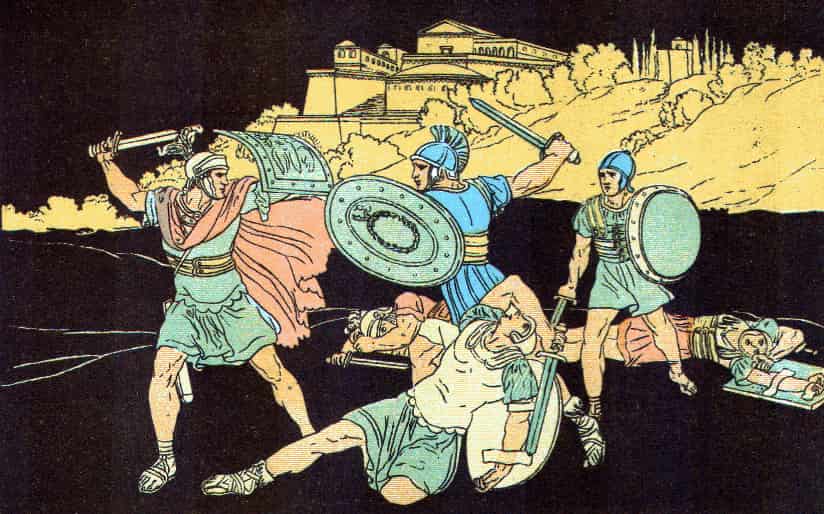

What we can learn form the story of the Horatii and the Curiatii

The story of the Horatii and the Curiatii would indicate that even the ancient Romans, with all their love for Mars, understood the horrors of war and sought better solutions. The story, as recounted by Livy, tells of the Roman king Tullus Hostilius’ war with the Latin city of Alba Longa. In order to avoid the ravages of war, the two parties agreed that the conflict should be settled by a fight to the death between the Roman Horatii triplets and a set of Alban triplets, known as the Curiatii.

During the battle, the Horatii wounded all three Curiatii, but two of the Romans had died in the process; so, in order to avoid fighting all three Curatii at the same time, which would have meant certain death, Publius, the remaining Horatius, began to run across the battlefield to entice the Albans to chase him. The ploy worked as the remaining brothers were separated from each other owing to their different speeds and he could thus dispatch them one by one. The Roman victory was respected by the Albans, but only for a short while. Moreover, having crossed that line and tasted blood, it only took minutes or hours before Publius killed again. No sooner did he get home, in fact, than he murdered his sister who had been distraught at the death of one of the Curatii who was her lover.

The forbidden fruit brought death into the world because the forbidden fruit was choosing death. No matter how we try to contain it numerically or through treaties and conventions, once we say killing is okay, we have crossed that line. Should we be surprised that Eden is not Eden any more when we stain it with blood? The rivers that flowed in Eden are the same, only now they reek of man-made death. For too long have we accepted the horrors of war, glorifying soldiers who we send to kill other soldiers, and, as Putin’s armies continue to prove, civilians. It does not have to be this way.

A gladiator in a Roman arena, may know that he has to fight to the death, his or his opponent’s. The is self-defence, even though his rival may be as innocent or as guilty as he is. It is often the same with soldiers killing each other. However, the gladiators or soldiers are not wholly to blame. They are often just pawns. The real culprit is the one or ones who create the rules of play.

When international law did not exist and a tribe chose to attack another, defending one’s rights was an act of self-defence, which, in legal terms is defined as “justification for inflicting serious harm on another person on the ground that the harm was inflicted as a means of protecting oneself.” (Britannica)

Now, we have international laws that legislate against the worst atrocities of war, although at present they offer no guarantee that they will not be flouted by a given party. The problem we face is, therefore, two-fold. On the one hand, our laws only cover the “worst atrocities” as though the lives of soldiers were worthless; while on the other, the will or means to enforce them is wanting.

No more soldiers

Soldiers should become a thing of the past.

As long as the word and institution exist, people will be sent to kill and be killed according to accepted rules of play. As I will explain below, we do not need them. Soldiers are people too, often young people at the mercy of older people who care little about their welfare and would sacrifice them for useless causes linked to antiquated ideas of nationhood or religion; sometimes simply as fuel to inflate their own petty egos.

Moreover, should they survive, they will often carry the scars, mutilations or trauma of war with them for the rest of their lives. Many lose all sense of decency, becoming a curse to any they can wield power over, killing, raping and torturing as they go along. They are simply taking the rule that killing is acceptable to the logical conclusion in the arena of war and sometimes beyond.

In my own lifetime, when witnessing unjust wars, like the 2003 invasion of Iraq, I often heard shocking statements like “well now that our boys are on the front, we should support them!” What absolute rubbish! The only way to support them is to bring those men and women home. Yet we are obsessed with the old lie: “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.”, which translates as “it is sweet and proper to die for one’s country”.

Wilfred Owen and the war poets do a good job at exposing that lie. Siegfried Sassoon’s poem Suicide in the Trenches does it poignantly and concludes:

“You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.”

Hence, first and foremost, it is the rules of the game that need to change. Legalised killing must never be an option during conflicts.

An international police force

International law has been broken; it is the international community’s responsibility to deal with it

What we need is an international police force that will deal with violations of international law as national police in truly democratic states deal with people or gangs who break national laws. Yes, this self-defence may involve violence, but it will always be a case of the international community protecting against violent aggression.

Putin is currently breaking international law, and even though it is hardly sufficient, he is allowed to get away with it as though it were only Ukraine’s problem. Yes, much of the international community is supporting Ukraine with sanctions and arms, but almost as though we were doing it a favour. International law has been broken; it is the international community’s responsibility to deal with it.

I am not saying that this will be easy. The United Nations has tried to go that way and mostly failed because of its dominance by world superpowers. Moreover, nations sometimes struggle to deal with drug cartels and other organised crime, so a rogue nation may also prove a challenge, as the might of the Russian Federation could, even if it were confronted by a global police force. Nevertheless, the answer is not to let the gangs or aggressive nations run riot or to fight them on their own terms. At the end of the day, no matter how complicated an issue is, with robust and enlightened international laws, violent conflicts will always be a matter of crimes countered by law enforcement, that is, police operations and justice. No nation will be left to bear the brunt of evil alone, as Ukraine is having to do at the moment.

Finally, should such a police force be able to interfere with sovereign states when these states are oppressing and killing its own people, like the junta in Myanmar? If Texas started to behave that way, the federal US government would. So, why not? Justice has no borders.