Read this article in Italian (Leggi questo articolo in italiano) →

Over the last few centuries, economics has been dominated by a doctrine of perpetual growth. The prevailing idea was that there were no limits to how much we could exploit the earth and its resources. Today we know better, but sadly, we still behave as though we did not. As Kate Raworth states in her book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist (2017), the citizens of the next few decades are being cultivated in a mindset that is obsolete for the 21st century as it is “rooted in the textbooks of 1950, which in turn are rooted in the theories of 1850.” This, she points out, is proving to be a veritable disaster.

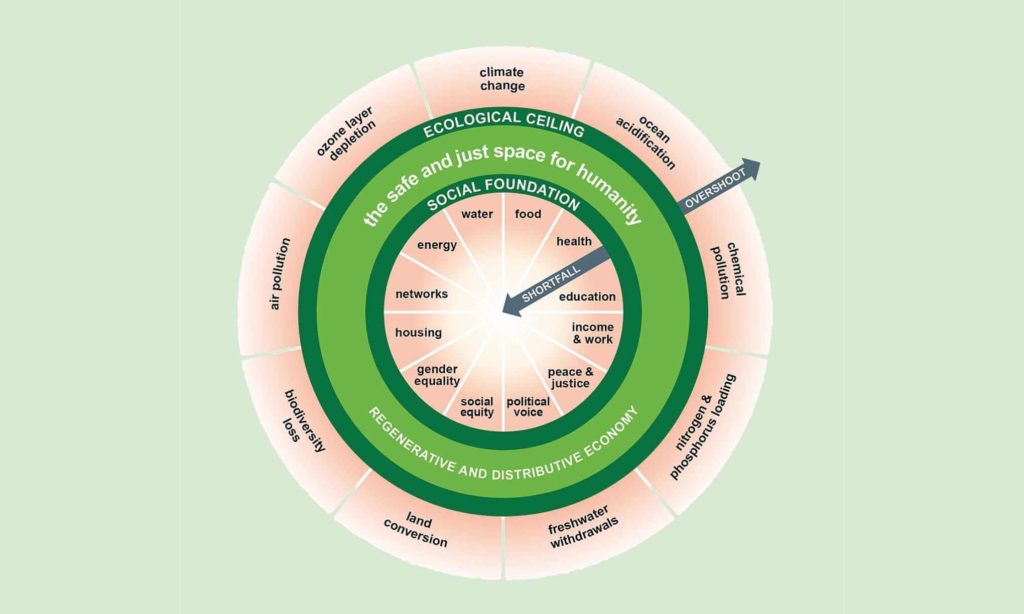

Kate Raworth first introduced her visual representation of what a healthy economy could look like in a 2012 OXFAM discussion paper titled: A safe and just space for humanity: can we live within the doughnut? The doughnut represented the safe space where humanity could thrive sandwiched between its inner and outer limits, namely our social and planetary boundaries:

“Achieving sustainable development means ensuring that all people have the resources needed – such as food, water, health care, and energy – to fulfil their human rights. And it means ensuring that humanity’s use of natural resources does not stress critical Earth-system processes…”

Raworth’s 2017 book develops the idea further. On the one hand she highlights how past economic theory has failed to grasp the full picture, while on the other she cautions that the picture is not a static one and as such requires a flexible and evolving approach. The seven “ways” she explores are simple, well researched, grounded and achievable.

1. Changing the goal

Raworth’s first point concerns Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which is generally accepted as the standard measure to assess value created through the production of goods and services in a country during a certain period. “GDP is a cuckoo in the economic nest” as a measure of progress because it tends to throw all other considerations out of the nest. Moreover, since its introduction 70 years ago, it has bound economies to a never-ending race. Indeed, the momentum of unbridled growth provides governments with certain perks, such as the increasing of tax revenues without the need to resort to the unpopular move of raising taxes, and the reduction of unemployment (Okun’s Law). However, the collateral damage is not worth the price. Onwards and upwards in no longer a fitting metaphor for the economy: “Instead of pursuing ever-increasing GDP, it is time to discover how to thrive in balance…” Reining in indiscriminate growth in order to preserve our social fabric and planetary equilibrium is not a luxury, but a matter of survival. The image presented by the doughnut highlights the boundaries that need to be respected in order to ensure stability wellbeing.

Though simple, this image requires effort and creativity to thrive, as well as the consideration of other factors, such as population, distribution, aspiration, technology and governance. GDP does not even come close to securing this safe and just space:

“In a few decades’ time we will look back, no doubt, and consider it bizarre that we once attempted to monitor and manage our complex planetary household with a metric so fickle, partial and superficial as GDP.”

2. Seeing the bigger picture

Seeing the bigger picture involves transcending limited economic models that distort a clear perspective. Paul Samuelson’s Circular Flow diagram, for instance, presents a rolling economic picture that appears “closed and complete”, as one dynamic feeds into another. In reality, however, it is “utterly flawed” and misleading as so many factors are left out of the equation:

“It makes no mention of the energy and materials on which economic activity depends, nor of the society within which those activities take place…”.

This is a serious problem because putting our faith in these models “has taken us to the brink of ecological, social and financial collapse.” Raworth offers a wider perspective including unpaid work that often makes everything else possible.

3. Nurturing human nature

One of the main criticisms against the Doughnut Economy is that a dramatic change of human nature would be necessary for it to work, as people would have to “magically” cease to be acquisitive and competitive (Branko Milanovic). The fact is that Raworth is far from naïve in this respect. She nevertheless rightly points out that “human nature is far richer”. Portrayals of people as self-interested, calculating and inflexible become self-fulfilling prophecies. Indeed, human integrity is easily eroded. Simply encouraging people to see themselves as consumers rather than citizens, for instance, can produce very detrimental results.

The price had gone, but the guilt hadn’t come back

One of Raworth’s examples of how human values can be easily undermined concerned an experiment at a school in Israel. Fines were introduced when parents turned up late to pick up their children, but instead of reducing lateness, it increased it, as parents saw the fine as a sort of payment. When the experiment was terminated, the late pickups rose further still: “the price had gone, but the guilt hadn’t come back. The temporary marketplace had, in essence, erased the social contract.” The same erosion takes place when financial incentives are used to promote decent behaviour. Inversely, cultivating human nature and emphasising trust in the community and pride in one’s cultural heritage produces very positive results.

4 & 5. Getting savvy with systems and designing to distribute

In order to progress in the right direction, it is necessary to abandon “economy’s elusive control levers” and start focusing on an “ever-evolving complex system.” Economics is a very particular sort of science, it ticks differently. When Alfred Newton lost his savings to the 1720 South Sea Bubble he lamented: “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men…”. An effective approach, therefore, involves keeping a finger on the economic pulse.

This system must also be inclusive. Sadly, economics is still cavalier about its moral obligations and well over two thousand years behind medicine when it comes to “honouring the ethics of its own profession.” These obligations should involve service to human prosperity, respecting the autonomy, engagement and choices of communities, minimising risks and working in a spirit of openness, and ongoing evaluation. In a word, recognising that inequality is not an “economic necessity” but “a design failure.” History has taught us that economic growth will not reduce inequality by itself; it needs to be managed:

“Today’s economy is divisive and degenerative by default. Tomorrow’s economy must be distributive and regenerative by design.”

6. Creating to regenerate

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

And here’s the hub: people power. Our author highlights how the trickle-down economy just does not work. The Kuznets Curve (ꓵ) which predicts that developing market forces first increase inequality but then decrease it, is a myth. Only last year, another OXFAM Report, titled Time to Care, confirms the fact: “Economic inequality is out of control. In 2019, the world’s billionaires, only 2,153 people, had more wealth than 4.6 billion people.” Despite the facts, however, the powerful few cling to the fallacy. Many people actually believe that rather than offering protection, hard earned policies like minimum wages and labour unions are barriers that need to be dismantled. As Upton Sinclair put it: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” Equally worrying is that the Kuznets illusion is being applied to other issues, such as the environment. Even if the Environmental Kuznets Curve were true, Raworth points out, the reality is that it would not be a solution as we would not survive its peak.

Several regenerative ideas are put forward. These include taxing non-renewable resources rather than labour, giving people a stake in robot technology, tiered pricing (higher prices for non-essential use) and redefining money so that rather than gaining value for sitting pretty, it actually lost value over time. Positive initiatives are, of course, taking root all over the globe, many of these, Raworth explains, also involve open-source technologies and ideas. The COVID-19 crisis we are facing just goes to prove how devastating patents can be. Big Pharma has recently blocked developing countries from producing their own vaccines even though the companies in question cannot even keep up with demand and honour their commitments. Letting people die is not what progress is about. What is required is an economy that is regenerative by design; one that overcomes the take-make-use-lose throwaway dynamics:

“This century needs economic thinking that unleashes regenerative design in order to create a circular – not linear – economy, and to restore humans as full participants in Earth’s cyclical processes of life.”

7. Being agnostic about growth

What Raworth means here is weaning ourselves from our addiction to growth and approaching it cautiously:

“Today we have economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive: what we need are economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow.”

This last statement sums up the vision; one that is certainly within our reach despite humanity’s current collision course. Tokenistic or half-way measures, however, are no longer enough. More stringent measures are needed than those that even organisations like the United Nations propose. Nevertheless, the question we need to ask ourselves now is not “how on earth?”, but “why on earth not?”

An optimistic vision and a workable one

“Doughnut Economics sets out an optimistic vision of humanity’s common future: a global economy that creates a thriving balance thanks to its distributive and regenerative design.” UN-aligned endorses the Doughnut Economy. Its benefits are clear and its flexible roadmap a safe trajectory for the foreseeable future. Kate Raworth’s book is easily available and you can also watch her explain the Doughnut Economy herself by tuning in to her TED Talk: A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow.

No doubt, implementing the necessary changes will not be easy, particularly when monster industries (like the meat and dairy industries) will need to be targeted, but the only other alternative is destruction, pure and simple.