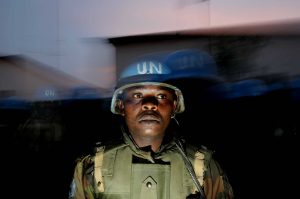

Poverty, to put it simply, is one of humankind’s greatest ills and despite various ways to quantify, analyse or measure it, the problem remains unsolved. With the world finding itself in unprecedented straits owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has not only claimed the lives of 4,000,000, but has revealed ominous and record-breaking poverty worldwide, humanity more than ever needs its leaders to come together and work towards effective solutions.

The UN initially committed to this duty in 2015 before COVID-19, where at the General Assembly its members set the ambitious aim of ‘no poverty globally.’ This was the first of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set to be achieved by 2030 ‘for a better and more sustainable future for all.’ 6 years on, amidst the harrowing COVID-19 pandemic, this article intends to evaluate the UN’s progress towards eradicating poverty and answer some key questions along the way:

- What is required to eradicate poverty worldwide by 2030?

- Has COVID-19 stifled progress?

- Is it time for a new approach?

What are the targets?

Here you can find the targets the UN set out to eradicate poverty globally by 2030. Now let’s break down the targets.

Target 1.1: eradicating extreme poverty

Before COVID-19, the UN admitted that 6 percent of the world would still be living in extreme poverty by 2030. The UN’s scepticism towards eradicating poverty will have been exacerbated with the COVID-19 pandemic, which according to the following statistics has made the UN’s goal even more unachievable. COVID-19 has:

- Pushed an estimated 71 million people into extreme poverty in 2020.

- Raised global extreme poverty in 2020 for the first time in over 20 years.

- Created bleak prospects: according to the World Bank, by the start of 2021, 150 million people would be living in extreme poverty

Target 1.2: reducing all forms of poverty

Before COVID-19, according to the SDG tracker (a useful tool created by the UN so everyday people can check the progress of the 17 SDG’s), a multitude of countries have either identified a rise of people living below the poverty line or recognised stifled progress with regards to citizens getting out of poverty. Some examples stand out:

- The proportion of people in South Sudan living under the poverty line increased from 65.60% in 2015 to 82.30% in 2017. An overall absolute change of +16.70% or 1,821,970 people.

- Thailand’s population living under the poverty line increased by 1.40% from 2015-2017. This means that there has been an estimated increase of 968,940 people living in extreme poverty.

COVID-19 has pushed a speculated 150 million people worldwide into extreme poverty, meaning the likelihood of achieving this task by 2030 is low, especially when compared to the progress made before its breakout.

Target 1.3: implementing social protection systems and measures

In 2016, an estimated 4 billion people did not benefit from any form of social protection.

An International Labour Organisation (ILO) report points out that between 2017 and 2019, 1.3 billion children were not covered by social protection, with several countries even reducing social protection for children. The countries most affected by a lack of social protection are located in Africa, Central America and South Asia.

Contrary to the prior two trends, COVID-19 has raised a fresh impetus upon the importance of social protection, with this sentiment being relayed by the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres: “The pandemic brings new awareness of the social and economic risks that arise from inadequate social protection systems.”

Yet, social protection spending has only increased for rich countries, whereas in low-income countries they were spending more on debt services and on average, the total per capita for social protection was as low as $4. Therefore, concentrated spending on social protection is required for developing countries for target 1.3 to be achieved. However, as the UN has not defined what an ‘appropriate social protection system is’, there is potential for the UN to claim success by manipulating the ambiguity behind this task to its advantage.

Target 1.4: equal rights to developmental opportunities

Target 1.4 has two primary criteria which gauge its success. The first is called indicator 1.4.1 which is ‘the proportion of population living in households with access to basic services.’ These basic services being drinking water, sanitation, electricity, and clean cooking.

In somewhat true UN fashion, both the target 1.4 and indicator 1.4.1 seem vague, with no transparency or defined guidelines as to what constitutes ‘basic’ drinking water, electricity, or sanitation. The UN’s confusing ambiguity has been reported upon broadly in academic circles and mainstream journalism, with common conclusions being that ‘SDG assessments are ambiguous and confusing.’

The data provided to the aforementioned SDG tracker only adds to the perplexity of monitoring the UN’s progress towards this specific goal. Data is only available up to 2016, which makes it hard to ascertain the progress achieved by countries in 2021 amidst the pandemic. Nevertheless, even with the limited data set, common trends, such as those in central Africa, indicate stagnation and limited access to basic services, meaning further investment is required.

Indicator 1.4.2 ‘securing tenure rights to land’, is even more confusing and vague, with no data available to check the UN’s progress. External research and data show that progress towards giving the poor and vulnerable land ownership is limited. Land Portal (an extremely established foundation dedicated to global land governance) has denounced the UN for lack of progress five years into its plan, where persistent land insecurity, land evictions and threats to land-rights defenders remain rife.

Data and statistics show that land has remained in the hands of the richest:

- Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population

- South Asia and Latin America exhibit the highest inequality with the top 10% of landowners capturing 75% of agricultural land

- Top 10% landowners in Africa, China and Vietnam capture 55-60% of available land.

Target 1.5: providing the poor and vulnerable with safeguards

Target 1.5 comprises many different indicators to gauge its success and provides more defined criteria such as the first indicator ‘reducing the number of deaths, missing persons and directly affected persons attributed to disasters.’

The overall trends that the SDG tracker provides seem to be in the UN’s favour with reduced death rates from natural disasters and less direct economic loss. Yet, most data available ends in 2017. In pre-COVID times, up to $23.6 billion were lost to Natural Disasters worldwide in 2018, meaning work still needs to be done.

Additionally, classifying COVID-19 as a natural disaster, as it has been in Pennsylvania, makes achieving this goal even more unlikely for the UN. Catastrophic consequences include:

- Over 4,000,000 deaths worldwide

- Women losing $800 billion globally

- A loss of $4.8 trillion to the US economy

- 79.5 million people displaced by COVID-19.

Targets 1.A (mobilising resources for developing countries) and 1.B (creating sound policy frameworks)

It is hard to gauge the progress of targets 1.A and 1.B since 2015 using the UN-based SDG tracker due to incomplete data.

However, according to the SDG tracker and other sources, government spending on essential services like health have increased. 2018 was a particularly prolific year, with global spending on health reaching $8.3 trillion (10% of global GDP). Nonetheless, these statistics were primarily from richer countries, and poorer countries are still struggling health-wise.

Additionally, COVID-19 amongst richer member states has seen spending on essential services skyrocket, with the UK for example putting an extra £63.4 billion towards health. Also, the US’s economic stimulus bill was a whopping $1.9 trillion.

By contrast, poorer countries are still being hit the hardest. Thus, without the investment, infrastructure, or resources to battle the financial implications of COVID, they will be stuck in an economic downturn for decades.

So is the UN is failing to eradicate poverty?

The overarching conclusion from this brief analysis is that COVID-19 has stifled progress for the overall goal of eradicating poverty once and for all by 2030. Yet, even before the COVID era, governments across the world were still projected to fail in achieving the UN’s targets by 2030, with some countries, such as South Sudan, spiralling into further poverty. This poor progress is especially surprising when considering the success of the UN’s Millennium Development Goal 1.A (2000-2015), where it achieved the halving of the proportion of people whose income was less than $1.25, 5 years before the deadline of 2015.

Additionally, by acknowledging that it would fail to eradicate poverty by 2030, the UN not only leaves a bitter taste, but an overall distrust in its problem-solving abilities. The UN’s failure calls for scrutiny with regards to what they did wrong and what is needed in the future to make sure the same mistakes are not repeated.

What went wrong?

This section of the article will concisely pitch main criticisms towards the UN’s limited progress towards achieving its first SDG.

1. SDGs are not legally binding.

- This is problematic as there isn’t any risk, penalisation, or potential sanctions imposed upon countries that fail to achieve the goals. This bodes the question whether the UN is genuinely 100% dedicated to achieving these goals.

- Also, the process puts unneeded pressure onto national governments that lack finance, infrastructure, and proper initiatives to achieve these goals. This is the case because the UN puts the onus on governments, irrespective of their abilities, to take ownership and establish frameworks to achieve these goals.

- The SDG’s not being legally binding and the vagueness associated with them reiterates problems of ambiguity as governments are left to their own devices to draft what constitutes as successful.

- The lack of a coordinated legal framework promotes nationalism over universalism. Top-down legislation from the UN which would take into consideration national resources, could put everyone on the same collective page instead of leaving countries to their own devices, which may spark competition instead of collectivism.

2. Growth does not reduce poverty

- Despite worldwide economies rapidly growing, like China and India, over 700 million people still live in extreme poverty

- Using GDP to solve poverty is not sustainable or effective and shows the failure of the UN to pursue more creative and challenging solutions.

3. No accountability for the UN’s action which increases poverty

- Human rights practitioner Philip Alston condemns the world’s leaders and the UN for failing to tackle extreme poverty during COVID 19 and believes ‘poverty is a political choice’. He calls for further accountability from the UN.

- The UN has failed to oversee and retain strict global corporate tax rates, which have fallen from 40.38% to 24.18% in 2019.

- It took the G7 rather than the UN to institute the historic global tax reform of 15%.

- There is no accountability from the UN for abusive trade agreements which see liberalisation of global markets at the expense of the poor.

4. Misunderstanding of poverty

- Academic scrutiny debunks the idea that $1.25 would be enough for people to get out of extreme poverty

- Studies suggest that $5 per day is required for people to break away from poverty; if this were the case, the poverty headcount would rise to 4.3 billion people.

These criticisms raise concerns regarding the UN’s dubious actions, which poses questions of what is needed to eradicate poverty.

How to eradicate poverty.

The answers are simple enough when it comes to eradicating poverty, but it would involve hard effort, incentives and overall impetus from the UN, which at this time it are not showing.

Both Former World Bank Group President, Jim Young Kim, and Victoria Kwakwa, Vice President of the World Bank for East Asia and Africa, suggest investing more in human capital at earlier ages. As this will mould future generations to be resilient against global shocks, displacement, and climate change. Other expert-backed solutions include:

- Fairer redistribution of wealth

- Develop strong social protection systems

- Investment in infrastructure and services for long term growth and sustainability

- Holding the rich to account.

Despite UN, World Bank or WHO experts suggesting solutions, we as a world are nowhere near completing the first SDG of eradicating poverty. This calls for introspection of what humanity could achieve under a new world order that was dedicated towards humanity, not greed. This is the ethos of the ambitious and alternative United Nations called UN-aligned. The world under their guidance would make the aim of eradicating poverty more realistic and not a pipedream, as it is under the current tutelage of the UN.

What can UN-aligned do better?

UN-aligned promotes a series of solutions aimed at eradicating poverty once and for all, which not only correlates with expert-based solutions, but enshrines humanity at its core. This precedent is unlike previously disclosed UN policy, which cherishes greed in the form of archaic growth-based initiatives and trade liberalisation imbalances to eradicate poverty, which rather exacerbate the problem further and perpetuate the financial status quo. Some policies proposed by UN-aligned to eradicate poverty include:

- Eradicating poverty outright

- Limiting money hoarding

- Working towards a fairer distribution of wealth

- Nationalising banks

- Ensure governments’ role in upholding their nation’s infrastructure

A future where the world order prioritises humanity over greed looks promising and this is one of the foundations of UN-aligned. Humanity pulling together can eradicate poverty once and for all, while the UN’s lack of progress towards this goal means that we, humankind, should search for other solutions instead of blindly following its lead. UN-aligned is one of these solutions.

If you nod in agreement with these principles and desire further information about the UN-aligned cause, check out Adrian Liberto’s book ‘Unravelling the United Nations Argead Style’ which highlights the UN-aligned cause in greater detail. Additionally, to show your support you can become a member of the cause.