The UN defines torture as cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment which deprives individuals of their basic human needs to the extent that it inflicts harm. Solitary confinement clearly reaches this bar, stripping prisoners of their rights to socialisation at the cost of their mental health.

Solitary confinement often achieves fewer goals than keeping prisoners under control more quickly and satisfying a perverse need to see pain inflicted on those deemed criminally responsible, with little regard for the consequences. In doing so, the prolonged use of solitary confinement contravenes many national statutes. These include the 8th Amendment to the US Constitution, the Nelson Mandela Rules put forth by the UN, China’s Prison Law and European Prison Laws. In 2011, UN Special Rapporteur for Torture Juan E Mendez claimed that in many cases, it breaks international law, and he has called for a ban.

What is solitary confinement?

Solitary confinement is the practice of keeping people, most often prisoners, alone for the vast majority of their day, with minimal social interaction or stimulation. Researcher Sharon Shalev describes the conditions in her 2009 book ‘Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Solitary Confinement:

- Cells are typically slightly bigger than a typical lift, comprised of a bathroom and sleeping area

- People are held in these cells for between 22.5 and 24 hours a day, only allowed out once a day to walk up and down a small corridor alone

- There are no group activities at all and very few rehabilitative programmes

- Limited visitors, in many cases none for years, and then only thick pane of glass

In 1955, the UN adopted the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. These created guidelines about how prisoners should be treated and were expanded in 2015 to become ‘Nelson Mandela Rules’ in celebration of one of the most celebrated prisoners of all time. The rules dictate that solitary confinement should only be used in circumstances where it is the last resort.

UN Special Rapporteur Juan E Mendez has stated that ‘solitary confinement is a harsh measure, contrary to rehabilitation’ – the purported aim of the penal system. He claims it can amount to torture, should not be used for more than 15 days with any person, and should not be used at all in the cases of minors or those with disabilities. In cases where it is used, authorities should follow a set of guiding principles for safeguarding.

Despite this, solitary confinement is used widely globally. A 2016 UN report found that most countries that use solitary confinement do so punitively. One of the most prolific users of solitary confinement in the world, the US, has between 80,000 and 100,000 prisoners in solitary confinement at present.

What are the consequences of solitary confinement?

12 times more likely to die

Its consequences are stark and, in many cases, permanent. American prisoners who experienced one placement in solitary confinement were 17% more likely to experience premature death of any kind and 55% more likely to commit suicide than similarly matched prisoners. For prisoners who had experienced multiple placements in solitary confinement, the risks more than doubled, with a suicide risk of more than 129%. In the first two weeks after release from prison, a person who has undergone solitary confinement is 12 times more likely to die than somebody from the general population.

One of the most significant casualties of solitary confinement is a loss of identity. Personal identity is, in part, defined by social interaction and where a person sees themselves fitting in the broader social order. People who are kept away from other people do not have these parameters to define themselves within, so they lose the sense of who they are. In many cases, they lose their sense of being all together and begin to question if they even exist.

Sturt Grassian examined the psychological impacts of solitary confinement, identifying that it induced a novel psychiatric illness. The symptoms of this illness were similar to those of anxiety (panic attacks, intrusive thoughts, hyperresponsivity to typical daily stimuli) but also included: overt paranoia; problems with impulse control; and difficulties thinking, concentrating and remembering. This collection of symptoms is distinct from any other mental illness and impedes the capability of a prisoner to function anywhere outside of solitary confinement.

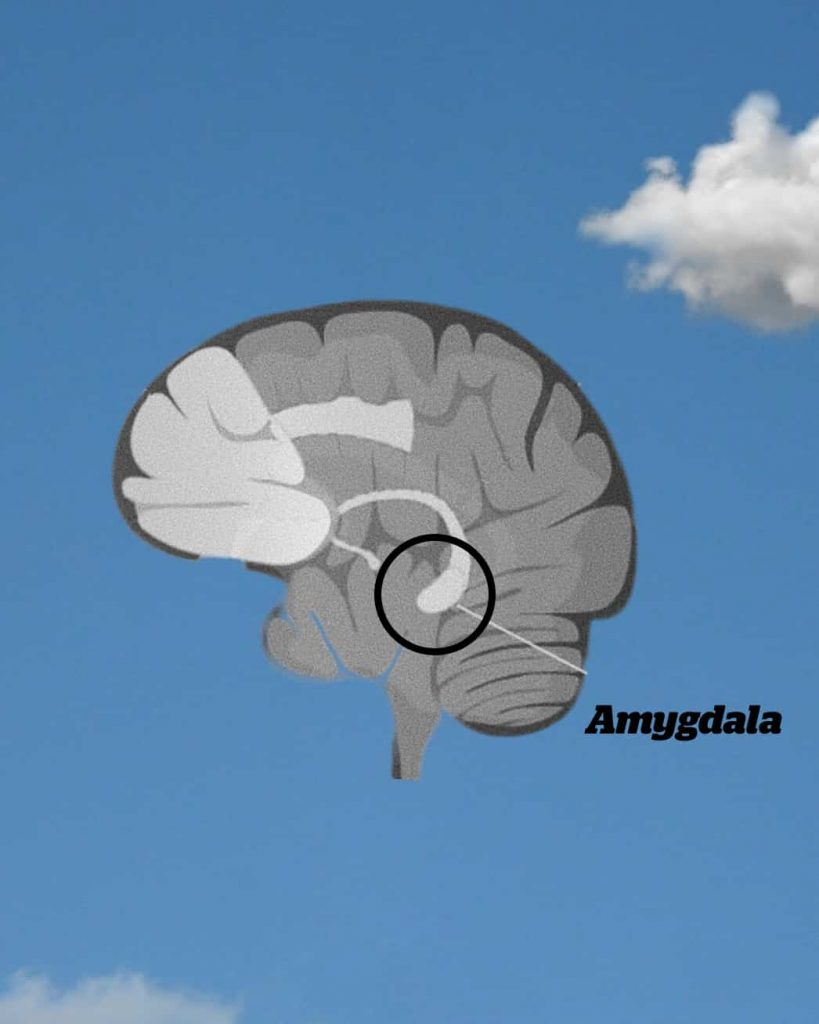

Robert King was part of the Angola Three, a trio of men who were kept in solitary confinement for twelve years after being convicted of killing a fellow inmate. His state eventually overturned his conviction. Whilst investigating the impacts of solitary confinement on King, researchers found permanent neurological damage. King has lost several cognitive faculties, has an impaired memory, and now finds it difficult to navigate his surroundings. He experienced psychosis and changes in how he experienced external stimuli. Much of this damage is indicative of damage to the hippocampus, the area of the brain that is involved in memory, spatial orientation and emotional regulation.

These findings are consistent with the work of neuroscientist Richard Smeyne, who found that after just one month of solitary confinement, neurons in the sensory and motor regions of the brain shrunk by 20%. On the other hand, the amygdala (the area of the brain responsible for fear and anxiety) increased its activity in response to solitary confinement.

Likely, as a result of this illness, the risk of reoffending is higher for prisoners in solitary confinement. The risk of reoffending in all crimes is around 15% higher for prisoners who have experienced solitary confinement. It rises to approximately 25% higher for violent crimes. These discrepancies are hardly surprising when considering that many of the symptoms characteristic of solitary confinement syndrome are risk factors for offending. Research has demonstrated that low impulse control, intrusive thoughts and overt paranoia may increase the likelihood of violent criminal behaviour, as a detachment from reality forces a person to interpret others’ behaviours as threatening when not intended.

Solitary confinement is torture. Very few say it better than Charles Dickens:

‘I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore the more I denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.’

It is inhumane and harmful to the highest degree, comparable to even the most heinous physical tortures. The UN must work harder to prevent its use globally, regardless of the power its main perpetrators have over the organisation. Anything else is negligent.