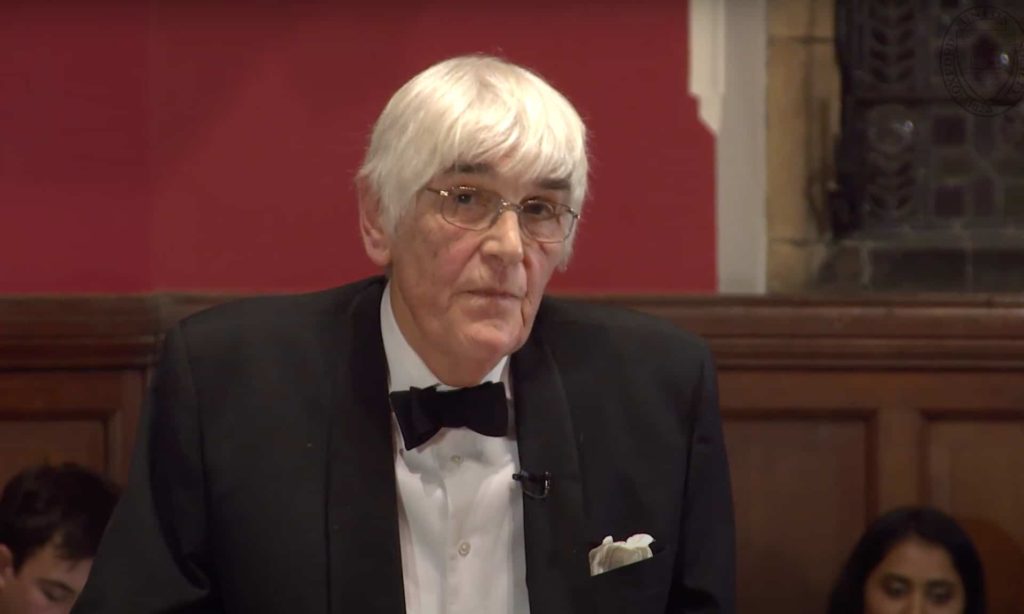

Last week Edward Mortimer, the chief speechwriter for Kofi Annan, passed away at the age of 77. He was described as “one of the lively minds surrounding the Secretary-General, given license to think and experiment at a time when the future of the United Nations was being written anew”. We wish his friends and family our deepest condolences.

Today, however, we would like to point your attention towards a peculiar speech he made to the Oxford Union in 2017 defending why the United Nations is not a failing institution.

Mr. Mortimer did acknowledge that the UN had its faults, but instead decided to debate why the UN was essential for the modern world. Standing at the Oxford Union’s dispatch box, he argued that the UN possessed a special and unique legitimacy because of its universal membership. Although he did acknowledge that this is an airy-fairy and abstract statement, he went on to deliver quite a wacky speech.

1. The “there is a unique legitimacy about the UN” argument

To prove this so-called “international legitimacy”, Edward Mortimer tells a story about the Iraqi invasion in 2003. Following the Coalition Provisional Authority’s refusal to democratically hand over power to the sovereign government, Ayatollah Sistani, an influential Iraqi Shia cleric, asked for the assurance of the United Nations that the new government would be elected by the Iraqi people.

He continues by describing a meeting in the basement of the United Nations headquarters, which included Paul Bremer, Ahamd Chalabi and Abdul Aziz Al-Hakim, amongst other key figures in the Iraqi government, where the participants did everything, short of “getting down on their knees” to Kofi Annan, to convince him to send someone to reassure Sistani.

This he points out is “what legitimacy is about”. Later, he claimed that there is no other organisation that can provide that.

Although Edward Mortimer may have a point when he refers to the profuse and diverse members of the UN, many of whom have floated pretty much all forms of decency, he leaves the listener with one giant question.

With the Security Council at its heart, isn’t the UN’s raison d’etre the maintenance of international peace and security? So how come, two of its permanent members, the UK and the US found themselves invading Iraq?

2. Let’s not pretend the Security Council is not part of the UN

When in March 2003 the US hawkishly declared that “diplomacy had failed” and that it would proceed with a “coalition of the willing” to rid Iraq of weapons of mass destruction it so desperately (and of course falsely) insisted it possessed, everyone in the UN was powerless.

This is the first hole inside Edward Mortimer’s argument. The Permanent members of the Security Council have been tasked with an extraordinary mission: to preserve international peace through upholding international law and regulations. But looking back at the UK/US coalition that led the destruction of Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and, by proxy, Yemen, amongst many other places, the US and the UK seem less concerned with maintaining “International law”, but rather keen on upholding an attitude of “might makes right”. Adding China and Russia (two other permanent members of the UNSC) to this coalition of chaos takes this gangster “law,” rule on an international level.

Was 2.4 million Iraqi deaths worth it?

Many may argue that the Iraq invasion violated the UN Charter as well as UN Security Council Resolution 1441, others may insist that the war was perfectly justified as the law of war authorises the use of force in the case of “self-defence”. Many however seem to hail the invasion because it got rid of the Iraqi dictator Sadam Hossein. To all those subscribing to this thesis, however, I liked to ask one question: was 2.4 million Iraqi deaths worth it?

In the case of Iraq, the UN’s failure to fulfil the promise of promoting peace and security and protecting human rights offers a clear example of how ineffectual the organisation can be. The ICC, the ICJ, the Security Council, amongst other UN bodies, were all powerless to stand up and hold the US and the UK accountable for their war crimes.

Eventually, various UN agencies did what they could to help Iraq. In August 2003, for example, at the request of the Iraqi government, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) was formed. However, by now, all of this felt less like peace maintenance and more like cleaning after the US and the UK.

The demented logic Mortimer chooses to ignore…

You may be thinking that surely within a large organisation like the UN, there must be someone to turn to. Well, good and bad news: As outlined in Article 39 of the UN charter, there is someone that can rule on the legality of the war, but brace yourselves, it’s, surprise, surprise, the UN Security Council, a place paralysed by the uncontrolled vetoes of the very accused. This is precisely the kind of demented logic that Edward Mortimer chooses to ignore.

Needless to say that to this day, all five permanent members of the Security Council continue to get away with their self-interested agendas, without being subject to any sanctions or prosecution.

3. The “International law must not be breached” argument

Mr. Mortimer finishes his speech by saying that voting against the UN would issue a trump card for authoritarian rulers who are reluctant to accept the idea of international law. Again, taking a closer look at the Security Council’s resolution over Israel and Syria should make clear what countries hold themselves above international law.

Of course, it is likely that Mr. Mortimer speaks to those who think there is no place for the UN in today’s world. If this is indeed the case, he is absolutely right in insisting that the idea of the UN is quintessential to a unified world. However, not everyone who thinks the UN is a failing organisation does so with the intention of abolishing multilateralism and international law.

UN-aligned thinks the world of the United Nations’ goals and ambitions, we truly do. We believe that they are vital to promoting international law and human rights and effectively combat the climate catastrophe. We do not however think the current structure is fit for the challenges of the modern world. Read our manifesto to see where we stand.

Much like Edward Mortimer let us work towards a better United Nations, but this time, one that is founded on clearer ethical principles. Join UN-aligned to discuss and debate what this organisation could look like.