A critique of traditional schooling and a vision of a more dynamic system for the future

As a child, one gets fed a lot of crap from one’s elders. Fortunately, not all of it is swallowed. “You’ll see! As you grow older, you’ll look back at your school days and you’ll remember them as the best days of your life!” Whether the many grownups who preached this believed it or not (it may have been true for some of them), I wonder how they could have possibly thought that these words could have been considered reassuring in any way. It is like telling a prisoner in a torture chamber: “You think this is bad, wait until they put you on the rack!”

My life has not been easy, by any standards, but my school days still stand out as a little hell on earth. I expect I am not alone in this assessment, although for some, school may be that one escape from an even more oppressive environment; or perhaps some students may just find the atmosphere at their schools friendly and inspiring. Still, this does not make traditional conveyor belt schooling systems good.

The curriculum, the resources and the methods are more often than not designed to churn out pawns that will fall into the various squares that society has prepared for them. Some may think themselves privileged enough to occupy positions that may be less restrictive: the bishops (educators, healers…), the knights (law enforcement, military…), the rooks (builders, entrepreneurs…), but ultimately it is all the same.

We are being processed primarily to fill in roles within society: the supply that will meet the demand. Sure, schooling needs to provide some of that, but not only does our current system focus solely on that, it often does so to the detriment of a holistic education that will bring the best out of every student. In fact, as Carl Sagan make clear in this little clip, schooling generally snuffs the spark out of us:

Some of the reasons why I hated school so much were personal ones. I was slow, I was a foreigner, I was sensitive… Nevertheless, in a decent schooling system, these peculiarities should not matter, because a good education should exploit every ounce of individuality as part of the didactic process.

Alternative schooling

Technology has brought significant changes to traditional schooling; on the one hand because students are learning about it and on the other because it has provided opportunities and resources that did not exist before. Apart from this, however, teaching methods and educational curricula have evolved ever so slowly, and rarely with the courage needed to dramatically reform the system for the better.

Home schooling has always provided a certain freedom that has offered wider opportunities, but the success or failure of this method is very much at the mercy of the mentality of the parents who are offering it.

Apprenticeships have also proved quite liberating. One would think that whilst unbound in one respect, apprenticeships are nevertheless quite limited regarding range on the other. Again, this would depend on the approach of those offering it.

The education of Renaissance artists, for instance, often depended on apprenticeships with established masters, and whilst these produced outstanding artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo on the one hand, on the other, these very artists were polymaths par excellence.

The Renaissance man and to a certain extent woman, in fact, who relied extensively on mentors, is almost synonymous with polymath.

More recently, alternative schools have been attempted with varying degrees of success. The early 20th century saw a number of these schools emerge in the West, inspired by educationalists like John Dewey and Maria Montessori. In Europe, for instance, Paul and Edith (Cassirer) Geheeb, founded the Odenwaldschule (1910 – 2015) in Germany, which offered students a high level of independence and flexibility. Also in Germany, A. S. Neill founded a similar school in 1921.

The school moved to England in 1924 and is still thriving today as the Summerhill School. It prides itself on its “free-range” environment that sets out “to make a school that would fit the child rather than forcing pupils to do what parents and educators thought might be best for them.” In 1927, philosopher Bertrand Russell and his wife Dora founded the innovative Beacon Hill School in England, which focused on learning through activities. The school, which was primarily Dora’s concern, was hounded by authorities and financial problems and eventually closed down in 1943.

A renewed interest developed in the 1960s, particularly with the Free School Movement in the US, but this soon declined with President Nixon’s conservative policies of the 1970s.

The problem with alternative schooling

Despite being on the right track, the problem with these progressive schools is that they operate in a bubble, which can leave students at odds with the mechanisms of the “real” world they are then obliged to interact with. Also, being private enterprises, these schools can prove to be expensive to run and therefore expensive to attend.

What is needed in order to achieve the best results, is an overhaul of the whole education system that would make all schools progressive while integrating them with national education systems.

Apart from flexibility and more autonomy, which are already being asserted, these progressive schools need a meaningful curriculum that reflects the changing world we are living in today. Moreover, we must get rid of the dead wood; this should include classrooms, rigid age discrimination and exams.

These proposals may sound outrageous, but perhaps close look may show that they are not as fantastical as they seem.

How to create a meaningful curriculum

Let us look at the compulsory subjects in the British National Curriculum, for instance, they consist of: Mathematics, English, Science, Design and Technology, History, Geography, Art and Design, Music, Physical Education, Computing and Ancient and Modern Foreign languages.

These subjects seem useful enough, but if we examine the actual syllabuses of each, we will see that there is much to be done.

Let us take Mathematics for instance. I expect we would all agree it should be there, but the syllabus is another matter altogether. How many of us really care or need to know at what point a train travelling at a certain speed and having left at a certain time will intersect with another train travelling at a different speed having left at a different time, after both trains had certain Herculean labours to overcome in the meantime?

Do we really need to torture children with problems of this sort or with calculus, trigonometry and complex algebra?

Once we have learned how to add, subtract, multiply and divide, as well as how to work out simple percentages, we would probably have acquired all the maths necessary for most professions and our day-to-day life. If one is mathematically inclined, or wishes to choose a career that would require a more detailed mathematical knowledge, all well and good: the option should be there, but imposing it on children who have no love or talent for it is nothing short of barbaric.

Brain Teasers, on the other hand, can be fun and they can help children develop their problem-solving skills more creatively, as can basic algebra and basic geometry.

What is missing from the curriculum: However, what is equally problematic with the above curriculum is what is not on the list: Citizenship, Human Rights, Environmental Protection, Self-care, Cooking, Government (including taxes and the legal system), Budgeting, Film Appreciation, Driving, Job Hunting (and work skills, like teamwork and punctuality) …

These subjects are more likely to impact our lives and the lives of others than knowing what turns litmus paper blue or red, and yet we pass over them glibly.

It is all well and good to learn about the Black Death, but when our pandemic came along many people ended up behaving like idiots, simply because they just did not have a clue on how to act in real life situations.

No Classrooms! But what instead?

Let’s make schools theme parks for learning

Ideally, I would have opted for abolishing schools altogether, but they would have to be replaced by a range of easily accessible community facilities that would establish educational spaces in a whole range of public and private concerns: museums, hospitals, police stations, train stations, libraries, factories, government buildings, science labs, conservatories, observatories, farms, offices and so on.

Apart from the space and facilities, the mechanisms would also need to be in place so that children could learn without jeopardising respective operations. The teacher would become the conductor and the whole of society the performers. One could look at it as an unlimited apprenticeship scheme, subsidised by taxes, or rather a reduction of them. Such a scenario would take time and vision to materialise however, therefore, abolishing classrooms would seem like a good first step.

So schools can stay for now, but classrooms should go. In this scenario, schools would need be converted into learning spaces with science labs, mini-museums, theatres, art studios, music rooms, calligraphy rooms, reading rooms, gyms, computer labs, virtual travel arenas – as much like a holodeck as possible, supported by tour guides (history and geography teachers), games rooms (which would include a range of mathematical learning tools and challenges), language labs, kitchens, cafes, greenhouses and allotments.

Various artists, artistic enterprises and small businesses could be offered space within these buildings subject to an agreement that they would offer tutoring services that would be audited for quality assurance purposes.

In these revolutionary spaces, the closest thing to traditional classrooms will be conference rooms for various kinds of workshops. In other words, schools would become theme parks for learning.

No rigid age discrimination

As students develop, so will their interests and one of the main challenges will be to stimulate and educate children taking into account their different stages and abilities.

Learning how to read and write, for instance, will have to take place early on in a child’s education, while something like driving and work skills would be more appropriate for older children. Nevertheless, the system that mainly operates at present, where children are herded into classrooms strictly according to their age is solely of benefit to the institution, never to the pupil.

Student A may be several years ahead in music and a few years back in science: so be it!

Some children develop faster than other children and they may develop some subjects faster than other subjects. They should not be held back for the sake of the institution. This would require ongoing assessment and timely and coordinated booking of facilities. Periods should also take into account children’s limited attention span and though roll-on roll-off lessons would require too many staffing resources to be feasible, shorter lessons should be considered where appropriate.

Nevertheless, much of the learning will be self-managed and therefore these study periods could be self-regulated. The main point here is that age should never be a barrier to learning and progress.

No exams

If you have stuck with me so far, you will probably be wondering how such an individualised education could possibly be effectively assessed. The answer is simple: through portfolios. Every so often, children would have to present their portfolios which will evidence what they have done for that period. There would be a credit system and clear instructions on what would constitute evidence for each subject. The system would not be that different from the National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) that provide work-based learning qualifications in England.

There will be a quota of credits for limited mandatory subjects as well as quotas for optional ones. Subject selection can be linked with university entry requirements or specific professions that students can progress to directly.

By the end of one’s schooling, a student should have attained the required number of credits. Flexibility regarding the duration of one’s schooling therefore should also be considered: for instance, finishing two years before or two years after the standard time. Apart for being a fairer and more accurate method of assessing a student, the tyranny of examinations that have led children to suicide and breakdowns will be terminated. By allowing for more flexible school days and times as well, the drudgery of homework could also be eliminated. Of course, the devil is in the detail and there is no time for that in this short article, nevertheless, just as work-based learning has proved effective with the NVQ framework, so should a parallel school-based system work, given the proper thought, funding and support.

Making it happen and making it work

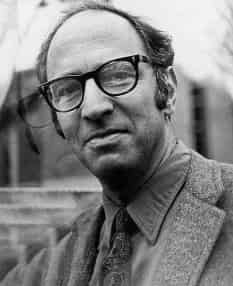

American philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn, had coined the term paradigm shift in his 1962 book The Structures of Scientific Revolutions to highlight the difference between “normal science” and revolutionary science, which often needs a generation in order to become accepted and take root. According to Robert Anton Wilson, when it comes to politics, religion and economics:

“Time-lags of centuries, or even millenniums, are common there.”

When it comes to education, we have waited millennia already. This paradigm shift is needed now. Technology has taught us how to run before we properly learned how to walk. This is dangerous, partly because of the war games that are being played out on the world stage, and, perhaps more crucially, because the world is going up in flames while we fiddle in a semi-stupor.

Money is not the problem. If we look at the budgets of developed countries, education is up there at the top with health and defence; and a progressive system of education as the one described above should not cost that much more than the current flawed one, especially once the necessary facilities are put into place. Moreover, making credits available from the private and public sector from the start could reduce costs. Students could also be registered with more than one school, so that neighbouring schools could specialise in specific subjects so that state of the art equipment would not need to be duplicated. The system itself could also work well in poorer countries, even though the resources necessary to maximise efficiency may take longer to materialise. Making use of the public and private sectors here would therefore be particularly helpful.

There is so much more to say about education and so much detail I have had to omit regarding the above proposals, but I think that I have said enough to introduce the idea of a paradigm shift in the way education is provided.

Significant change for the better, however, will not happen by voting for the same old idiots. Now is the time to be more courageous. Now is the time to help UN-aligned push for better institutions. Be part of that change by supporting us.