In memory of Rita Angela D’Alessandro, a beacon of love and generosity...

If talking about what you don’t know well is frightening, trying to convey to others what you have studied for a long time with enthusiasm and passion is disorienting, because you proceed with the constant feeling of not saying everything or at least not saying enough.

Years ago, when I was still a university student, I was deeply impressed by Christian archeology not only as a matter of faith, but because when art is placed at the service of any kind of religion or religious thought, it generates artistic phenomena that involve social edification. Among the various topics covered during the lessons, one in particular remained with me: the tituli.

The Titulus as a safe haven

The term titulus generically indicates the plaque placed outside the houses of ancient Rome on which the name of the owner of the dwelling was recorded in the genitive. Regardless of this specific meaning, the term titulus in the context of Christian archeology refers to a broader historical context, namely, that of the persecutions of the original Christian community. We are therefore talking about a phenomenon that, while continuing to exist over time, developed mainly up to 313, the year of the Edict of Constantine which made Christianity the official religion of the empire. During the persecutions, the faithful, for obvious reasons, had to meet secretly in order to carry out their rites.

Due to an incorrect cinematographic representation of this historical period, I have often found that many imagine the celebration of these rites to have taken place in catacombs. This completely inaccurate idea is to be dispelled because these environments that nowadays appear as hypogea, were, in the period of persecutions, mixed outdoor cemeteries mainly frequented by pagans.

Gathering in those places would therefore have had the same effect as giving one’e self up to the authorities. Although many speak of acts of religious fanaticism during the persecutions, the cases of voluntary surrender to the Roman authorities were, in fact, really limited, because in most cases the instinct for survival prevailed. Precisely for this need for security and protection, the faithful began to gather in places that they perceived as safe, such as the private domus (villa) of wealthy Christians.

These homes of the wealthiest Christians usually benefited from large spaces, often equipped with large gardens that sheltered the living quarters from public view. This level of privacy and lack of direct visibility from the street was not possible in the usual housing quarters of most Romans: the insulae. These were a sort of modern condominium that mostly housed apartments and commercial places, which left them more exposed and visible to the people who frequented them.

The domus made available to the community of the faithful began to be identified with the name of domus ecclesiae or titulus.

Through the acts of the synod of 499 we know that in that period twenty-nine of these tituli were registered in Rome. Historical references to the name of these structures remain today, but hardly any architectural elements bearing witness to the ancient houses. This is because with the end of the persecutions, the need to perform these cults clandestinely inside such homes no longer existed. The faithful, who could now meet publicly, financed the passage and transformation of the tituli into real public places of worship, which over time were transformed and expanded into magnificent basilicas.

Santi Giovanni e Paolo al Celio

Despite this transition from domus ecclesiae to basilica, or perhaps because of it, an ancient titulus has survived in Rome and it is opened to the public. It has remained almost entirely intact thanks to the structural changes it underwent at the time of its transformation into a basilica, which created a sort of time capsule.

It reveals aspects of everyday life of the pagan period and other signs that testify to the owners’ conversion to Christianity. This titulus Bizantis sive Pammachii, that is, the house of Byzante and Pammachio, is also known in the field of Christian archeology as the Celimontana house of Saints John and Paul.

The peculiarity of this title is that it was immediately a very popular place because it was there that two soldiers of the Jovia Legion, brothers Giovanni and Paolo, were martyred and buried. According to hagiographic data, the two were killed on the night between 26 and 27 June 363, by order of the apostate emperor Julian. After their death, the house became the property of the Christians Byzante and Pammachio who made it available to their fellow believers. It was frequented for the performance of rites, but above all in order to pray near the burial site of John and Paul.

Over time the flow of the faithful became so numerous that it was necessary to construct a larger basilica which was built by cutting the upper part of the Roman house and integrating it into the new and larger structure. Today, the new basilica, just like the ancient titulus, stands on the Clivio di of Scauro in Rome. Starting from the pavement of the basilica, in the late 1800s, the archaeological remains of the ancient church house were brought to light, which we can still admire today.

The surface of the ancient third-century domus is enormous, as is the number of finds that have come down to us. For obvious reasons, it will not be possible to examine them all. I will focus mainly on the examination of some subjects depicted on the walls of a room known by the experts of ancient art as the “aula dell’orante” (the hall of the praying one).

This choice is not due so much to aesthetic factors as to the interesting elements that testify to the transition from a pagan domus to a titulus.

The praying figure

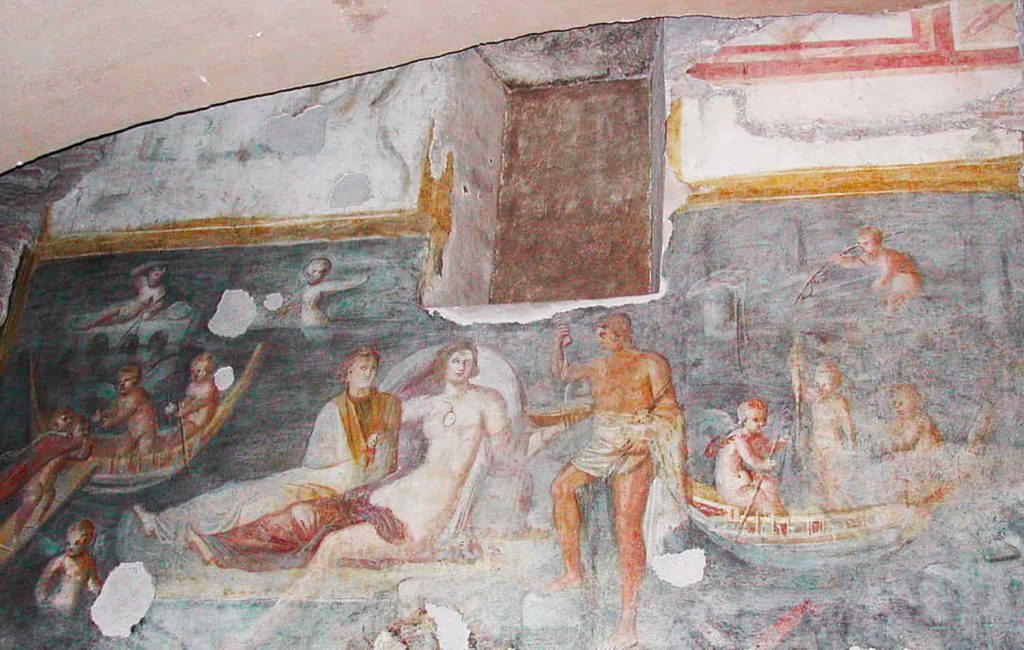

The lower part of the walls of the room, as often happened in the domus of ancient Rome as a means to evoke luxury and wealth, is frescoed with panels reproducing faux marble. The upper section, which was partly cut at the time of construction of the basilica, presents various interesting subjects. The pictorial decoration as a whole follows the curvature of the roof of the vaulted room.

The various spaces are divided by linear drawings, that is by red bands, which delimit the various spaces that host subjects of various kinds: philosophers with parchments and inkwells, animals next to a vegetable candelabra, imaginary animals, masks and fauns surrounded by leaves and flowers. These subjects have little in common with the Christian culture traditionally associated with the house, which is instead testified by the presence of the praying person; a figure who is usually represented in cemetery environments.

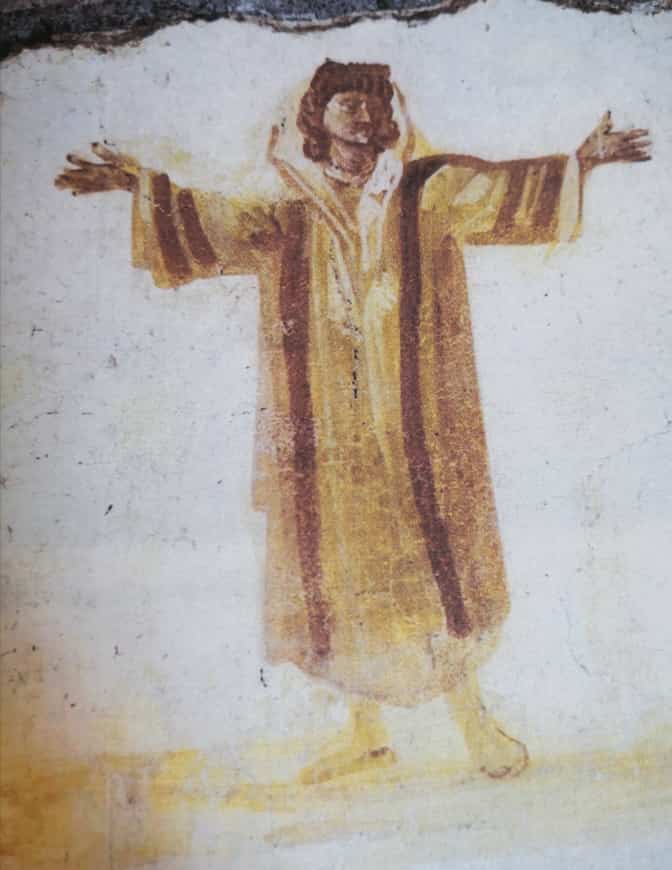

The praying person depicted on the vault appears dressed in a yellow Dalmatic toga, rigidly hung from the body to form a cross. The only dynamic element in this fresco is represented by the foot of the praying figure that appears to be about to dance, thus representing the joy of the soul that has achieved eternal salvation.

As indicated above, the figure of the praying person is often placed near burial sites and for this reason it could make us think of a private portrait of a deceased. In reality this drawing reproduces a woman with open arms. In the Christian context, this is a symbol of the soul, traditionally represented as a female figure. The outstretched arms and body of the woman evoke the cross and automatically associate it or the whole household to Christianity.

This habit of reproducing the soul with feminine features is actually a legacy of the pagan world where there is no lack of frescoes in which the body of the deceased is undoubtedly male, but the soul welcomed into the kingdom of the afterlife by Mercury is represented instead by a female figure.

Humanity at its best

The presence of the praying person, undoubtedly associated with pagan elements, contains the message that most struck me in the study of this period. Namely that in a moment of crisis and fear like the one experienced during the persecutions, arrogance and religious fanaticism did not prevail.

The testimonies of elements now perceived as culturally distant were not destroyed and there remained the harmonious coexistence of different cultures and ways of feeling.

The other lesson comes from the very nature of the tituli. During a time of great danger, people could offer hospitality to others, without prioritising their own safety and effectively exposing themselves to the risk of being betrayed in the event of the capture of other members of the community. The home, that even today represents our secure, sacred place, where we can shut ourselves up away from others, was transformed into a safe place for everyone.

For this very reason, this is a truly sacred location, far from personal selfishness and representing ideals that are purer and deeper than faith.