Read this article in Italian (Leggi questo articolo in italiano) →

“Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there!

He wasn’t there again today,

Oh how I wish he’d go away!”

The above quote from Hughes Mearns’ poem, Antigonish, could so easily allude to sanctions. They are full of sound and fury, and yet, they signify nothing concrete, but rather an absence of something. Of course, sometimes, a lack of something can have devastating effects: if you stop my air supply, for instance, I am dead. Sanctions, however, are very limited in what they can stop, because what comes from outside one’s borders was not there in the first place, like the man upon the stair.

Though countries may have become used to foreign luxuries like oil or pistachios, at the end of the day they can soon learn to do without them again. Take at Cuba, for instance, which has been under US sanctions since 1962! As for exports, well nations could find more creative means of adapting what they have, or diversifying their produce. At the end of the day, it is never a bad thing for a country to be self-sufficient; everything else should be considered a bonus. Nevertheless, sanctions are a lot more complicated than this, so let us take a close look.

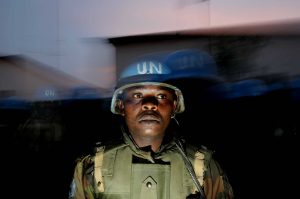

Sanctions are defined as “an official order… taken against a country in order to make it obey international law.” The United Nations (UN) considers itself the sole legitimate authority when it comes to issuing international sanctions against a rogue State, although any country can decide to impose sanctions unilaterally. Some, like the US, do this and additionally threaten other countries or independent agents with dire consequences if they do not comply with their sanctions regime.

In order to ascertain whether sanctions are a useful tool in the furthering of justice and world peace, we need to ask the following questions:

- What do they hope to achieve?

- What do they entail?

- Whom are they hurting?

- Have they proved successful?

- Is there a better option?

What do sanctions hope to achieve?

The aim of sanctions is simple: compliance. You either play by the rules, or you are out of the game. This is fair enough as long as the rules are just; and for this, we need sound international laws and the will to implement them. The February 1 coup in Myanmar goes against international law; that much is clear. However, the will to impose international sanctions on the military regime has been missing. The reasons for this are the same embarrassing power games played at the United Nations.

China and Russia love dictatorial regimes and since they are two of the five permanent members of the Security Council, they made sure that the resolution that was passed against Myanmar was as toothless as possible. China continues to assert that the situation there is an internal matter. This highlights an important factor in the mechanisms of international laws: they need to be worth more than the paper on which they are written.

Fortunately, the UN is not the only player. New Zealand, for instance, was quick to respond to the situation in Myanmar and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced strict measures against the coup leaders with relative speed the week following the takeover.

The US also sprung into action with an executive order targeting coup leaders signed by President Biden on February 11. The EU is also heading in that direction, though in a typically more ‘Entish’ fashion. Nevertheless, compliance does not seem to be on the agenda in Myanmar, whatever democratic institutions may throw at it.

What do sanctions entail?

Sanctions go back centuries. In 432 BCE, for instance, Pericles issued the Megarian Decree, which put a stranglehold on the Megarian economy through restrictive measures that included barring Megarians from harbours and trading hubs throughout the extensive Athenian Empire. The sanctions had been introduced as a punitive measure relating to the City State’s desecration of the Hiera Orgas, a precinct considered sacred to Demeter. Nowadays, the emphasis is on forcing a change of policy or regime, but the methods are more or less the same, though perhaps more targeted.

The sanctions policy of the European Commission offers a concise description of what is involved with regards to aims and methods:

“Restrictive measures (sanctions) are an essential tool in the EU’s common foreign and security policy (CFSP), through which the EU can intervene where necessary to prevent conflict or respond to emerging or current crises. In spite of their colloquial name ‘sanctions’, EU restrictive measures are not punitive. They are intended to bring about a change in policy or activity by targeting non-EU countries, as well as entities and individuals, responsible for the malign behaviour at stake.”

It breaks down its methods as:

- arms embargoes

- restrictions on admission (travel bans)

- asset freezes

- other economic measures such as restrictions on imports and exports

Arms embargoes are straightforward, as are restrictions on admission and asset freezes which are also specific, targeted and generally fair. The issue is always with the fourth point which regards economic measures. Restrictions on imports and exports, for instance, is a double-edged sword because trade goes both ways. Often, self-interest makes these kinds of sanctions impractical. Take Germany’s dependence on Russian gas as an example (Nord Stream 1 and the controversy over Nord Stream 2). How many ‘Crimeas’ or ‘Navalnys’ would we need for this trade agreement to buckle?

Collateral damage

Once again, arms embargoes, travel bans and asset freezes are more likely to be fair, in as much as they can target governments and individuals with relative precision. Of course, sometimes, ambitious athletes or other civilians may be caught in the crossfire. Economic measures, however, are quite another matter. It is unlikely that the likes of Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un or Hassan Rouhani will ever go hungry.

It is the people in the street that suffer, like the Venezuelan entrepreneurs and their employees who can no longer keep their businesses going, or the carpet weavers in Iran who are blocked from selling their laboriously created goods abroad. These are the people sanctions are meant to help, but the ones who bear the brunt of the measures.

Despite this, many of these victims may well welcome the measures imposed on their country because they show that the world is listening, while at the same time, sanctions may give them hope for a better future. Encouraging optimism alone, however, would not be a valid enough reason to warrant the imposition of this suffering on so many people. Sanctions have to work. If not, they are primarily a punishment, but one that hurts the wrong people.

So, do sanctions work?

Often, they do not. The Megarian Decree, for example, was actually one of the causes that led to the Peloponnesian War, which Athens lost. More recently, after Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations voted 50 – 4 to impose sanctions on Italy. However, restrictions on oil imports, which could have ground the Italian war machine to a halt, was exempted because Britain and France were afraid that such a move would throw Mussolini into the arms of Hitler… We all know how that story ended. We can see the same hesitancy today in President Biden’s stopping short of imposing sanctions of Saudi Arabia for its human rights abuses in case it turns to China or Russia.

Sometimes they do work. The general consensus is that they were instrumental in ending South Africa’s apartheid regime. In 1962, the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1761 called for sanctions on South Africa. This was not a Security Council resolution and therefore it was not binding; nevertheless, it could not be ignored.

By the mid-eighties, calls for sanctions had become louder and despite the resistance of US President Ronald Reagan and UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who did not want to alienate an anti-communist ally (or so they said), sanctions were passed by both governments.

These were not isolated incidents. By oppressing its own people, South Africa was being increasingly ostracised by the rest of the world. Awareness was growing at every level. More and more shoppers were boycotting South African goods, and companies, including many universities, were beginning to disinvest, triggering a capital flight. On top of all this, South Africa was at war with three of its neighbours. Apartheid was officially ended in June 1991 and the first multiracial elections followed in April 1994. Sanctions worked, but they were part of a much bigger picture.

Just another tool in the box

So yes, sanctions can work, given the right conditions, but they are by no means a panacea, particularly in our polarised world where big players are always happy to welcome a rogue State into their fold, or play the rogue themselves. South Africa did not have that luxury. Its fascist policies could hardly allow it to flirt with the Soviet Union or Communist China.

Also, as we have seen, vested interests often take the bite out of sanctions, or stall them altogether. Besides, as nations are relearning to be more and more self-sufficient, sanctions are becoming less and less effective. No doubt they can help, but they have to be a part of a bigger onslaught. For a country to simply slap sanctions onto a State and then get back to business is as good as saying it really cannot be bothered to deal with the problem.

Something more reliable is needed

If we lived in a federal world order, the solution would be simple: police action. If your neighbour decided to beat his wife and torture his children, you would call the police and they would arrest the culprit. If your local council decided to ignore national law by starting to incarcerate citizens in order to steal their properties, the national government would step in and restore law and order. If the State of New Jersey decided to issue a law that allowed it to kill anyone over retirement age, the federal government would intervene and punish the culprits.

There are no complications. There are two reasons for this. First, the overriding law; second, a police force powerful enough to stop the transgressions. A federal world order could ensure States were ultimately answerable to international law and small enough to be brought into line should they flout international law. This is the type of world order UN-aligned is striving for. There are, however, some essential provisos:

- International law must promote human rights, animal welfare and environmental protection.

- International law must focus solely on essentials so that individual States have the flexibility to legislate as appropriate to protect and develop their respective cultures.

- The people responsible for upholding international law have to be rigorously selected to ensure compliance and impartiality.

- A police force capable of intervening when a State begins to oppress its citizens, damage the environment or abuse other life forms.

A tall order, especially because it would require national governments to willingly hand over power to an overriding authority. Nevertheless, in a way, that is exactly what happens when states join to form a federation. Also, in a more limited way it is what states agreed to do when they chose to join the United Nations. The tragedy was that the UN was flawed, as my recent book, Unravelling the United Nations, highlights. So, the tall order may not be that tall after all, We just need to believe it is possible and work towards it, Then, perhaps, sanctions will become a thing of the past and the man upon the stair will finally go away…