How Michelangelo’s "Fruit Basket" captures the fleeting essence of life

In Caravaggio's 'Fruit Basket', a mere wicker basket and its contents emerge as a profound meditation on life, light and the passage of time, showcasing the artist's early genius.

I have always postponed examining the canvas: the “Fruit Basket” for various, and undoubtedly futile, reasons. The first and foremost relates to the subjects, or rather objects to be examined. In fact, the absence of any human presence seemed to me to be an almost insurmountable hurdle in my search for feelings, in contrast to the various subjects depicted by Caravaggio in his other works. Moreover, the setting of the canvas also initially blocked me, because it lacked the obvious theatricality of Merisi’s Roman works.

To overcome the various elements that inhibited me, I had to revisit, as if it were the first time, not so much Merisi’s artistic production, but his training. In fact, this canvas, created between 1597 and 1600, marks the arrival point of the painter’s artistic education and mirrors the environment in which he grew up, including the realistic elements of the Lombard school and clear references to the style of Giorgione.

Despite his young age, Caravaggio immediately demonstrated that he had not only internalised the teachings received but also that he had surpassed them. Indeed, all the technique learned in his years of training was immediately put into practice with originality and extraordinary audacity.

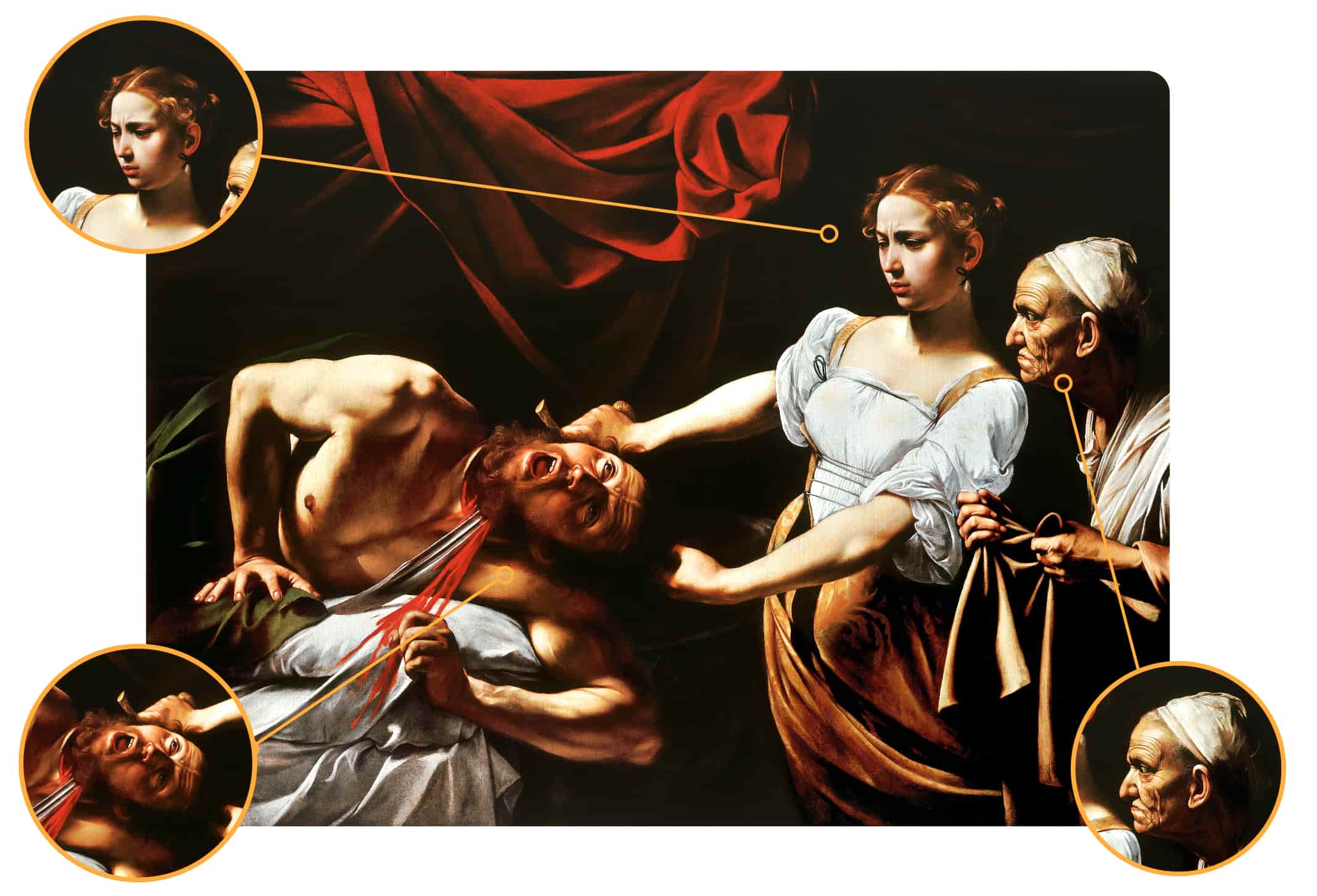

The Lombard tradition of depicting subjects through direct observation, however, is put into practice with a clear and new interpretative reference to the frescoes of fruit baskets from the Roman era. Nevertheless, Caravaggio did not limit himself to copying the ancients; he went further by interpreting the tradition of the past through his own artistic language, which is characterised by a new and personal way of setting the light and transforming it into a fundamental element that underlines the strong features of his work.

In this case the light is channelled to underline and enhance the mastery of the weaving of the wicker basket and its protrusion, compared to the supporting surface, a trick that gave the basket a three-dimensionality never seen in the ancient works of the classical age. This established a sure starting point for Merisi’s canvas.

Just as in the artist’s later production, here too the light enhances the beauty and indeed the dignity of humble things: a wrinkled leaf, a bruised apple and the blush of the grapes. It is as if the beauty of the various fruits is evident, but not idealised. This is because the type of beauty that Merisi wanted to exalt in the fruits, and which he will then portray through his characters, is not crystallised in time, but rather lives in the inevitable flow of time itself, which in its progress leads towards death.

This celebration of life and death, enhanced by the light, shadow, colour and three-dimensionality of the fruit basket, already contains the profound mystery of the art and the vision of life that Caravaggio would later shout to the world in the production of his artistic maturity.