After our overview of post-war British drama with a survey of the Theatre of the Absurd, let us now look at another important literary movement that developed after the end of World War II.

The end of the war left a sense of discontent and disillusionment, especially with the younger generation. As society developed into a more affluent capitalistic and class-conscious structure, the younger generation became aware that the poorer classes were being exploited and this prompted them to voice their anger. A new class of writers, known as the Angry Young Men, came into being. They were expressing their anger through various literary genres, in particular through prose and drama.

The term, taken from Lesie Paul’s Angry Young Men, described all those playwrights, poets and novelists who expressed their anger and sarcasm against the emerging social friction between classes. The novelists who best captured this sense of frustration were undoubtedly Kingsley Amis, Alan Sillitoe, John Braine and David Storey.

As regards drama, the most significant playwright who represented the Angry Young Men was John Osborne, who we shall be taking a closer look at. Two other playwrights worthy of mention are Arnold Wesker and John Arden.

Wesker dealt with the discontent of the working classes with his politically motivated productions. He focussed on the problems of the individual by showing that each person’s troubles were actually triggered by the flaws of society, rather than by individual weakness. John Arden, on the other hand, dealt with the wider issues of postwar society. His best work was certainly Musgrave’s Dance (1959), which was influenced by Brecht. Arden studied the intricate nature of war and peace in light of the changing society.

John Osborne: life

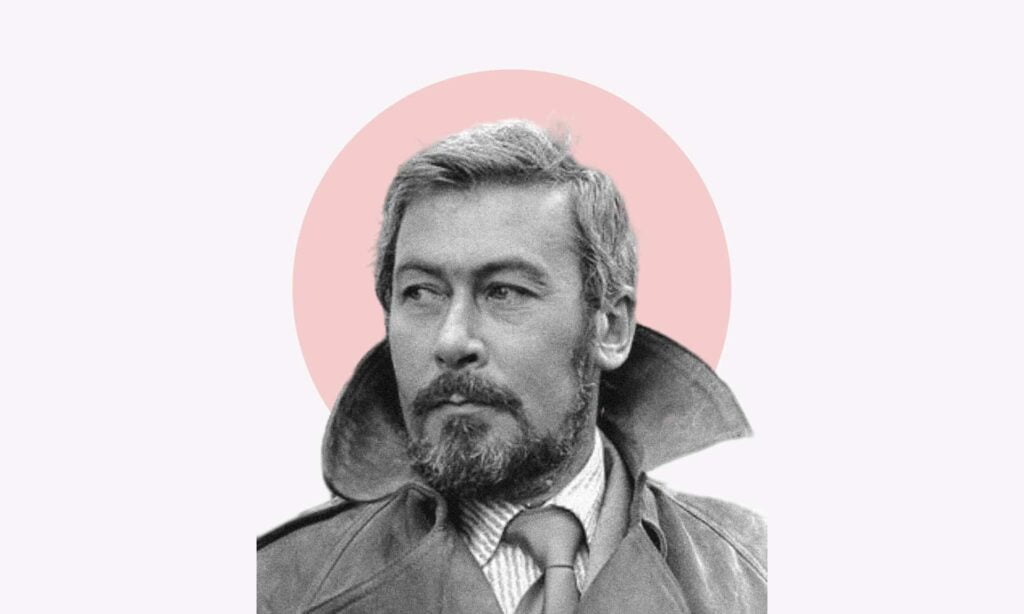

John Osborne was born in London in 1929. His father was middle class and worked as a copy-writer while his mother, a barmaid, was of a lower class. John Osborne was therefore brought up in a type of social stratum which did not belong to any specific class. He was not able to identify either with the middle class or with the lower class and so grew up in that strange condition of constant struggle to reach an acceptable respectability. This social limbo into which Osborne was introduced from childhood affected his work as a playwright. The changing situation of post-war England was tangible. The Labour government introduced the Welfare State and the younger generation began to reject the conservative values of the past.

Politically, Great Britain found itself in a situation which was no longer one of supremacy. The two superpowers which had emerged from the Second World War were the United States and the Soviet Union. Osborne later focused on these themes of Post-War social turmoil and changing values. He had left school early and was plunged into that society in the deep end, at first working as a journalist for trade papers and then as an unsuccessful actor. However, it was his experience as a theatre actor which helped build his craft as a playwright. His sense of stage, movement and drama blended with his sense of social struggle and awareness. These ingredients contributed to the overwhelming success of his first major production, Look Back in Anger (1956). Many successful plays, TV scripts and film scripts followed. Together with director Tony Richardson, Osborne founded a successful film company which brought him international recognition. He died in 1994.

Literary Career

Look Back in Anger, released in 1956, was most certainly Osborne’s first successful play. It was not, however, his first. In 1950 when he was just over 20, he wrote, in collaboration with Stella Linden, The Devil Inside Him and in 1955 together with Anthony Creighton he wrote Personal Enemy. Two of his later plays, Epitaph for George Dillon, written in collaboration with Creighton, and Paul Slickey, a musical play, were also written before his successful Look Back in Anger.

In 1957 Osborne released The Entertainer, a play about a music-hall comedian, Archie Rice, who becomes an alcoholic due to his inability to feel successful. His failure seems to reflect the failure of English society in general. The play was later made into a successful film production. In 1961 he wrote Luther, a historical study on rebellion, based on the life of the Protestant leader Martin Luther King. Inadmissible Evidence (1964) was probably Osborne’s most successful play after Look Back in Anger. The story was about a solicitor whose disdain for society slowly projected him into complete isolation. Other plays produced during the 1960s were Plays for England (1962), A Patriot For Me (1968), and The Hotel in Amsterdam (1968).

In 1960 Osborne wrote the successful TV play entitled A Subject of Scandal and Concern and in 1970 he continued with his TV plays, releasing The Right Prospectus and Very Like a Whale. A year later he wrote West of Suez and in 1972 A Sense of Detachment, two plays which were accepted very well by the critics. In 1981 the first volume of his autobiography A Better Class of Person was published.

Style and Themes

Social Injustice is one of the major themes in the works of John Osborne.

The term Angry Young Men was coined in the wake of his Look Back in Anger. Osborne attacked the complacency of the English and the society that had developed after the war. The main character Jimmy Porter exemplified human suffering and the social struggle which afflicted the youth in that period. The angry young men were those who belonged to the lower classes, but who were given the chance to exploit a complete formal education; neo-intellectuals who reacted to the old conservative standards of class distinction with strength and disdain.

Another characteristic of Osborne’s work is his intricate study of the generation gap which created the dichotomy between the stable values and national greatness of the past, and the social protest and declining importance of Post-War Britain.

Osborne’s style is innovative in many respects. The structure of his plays reversed the traditional settings and conventional parameters of post-war English drama by doing away with classical theatrical methods. The structure followed the basic three-act play created by the French dramatists Eugene Scribe (1791 – 1861) and Victorien Sardou (1831 – 1908). Osborne did away with flashbacks and created a circular development in the progression of his story. In Look Back in Anger, for example, the setting in the first act is identical to the third act, a fact which underlines the repetitive nature of daily routine. Apart from the social sense of frustration in Osborne’s plays, which marked a break from the traditional themes belonging to pre-war Britain, the language was also a uniquely distinctive innovation. Whereas the language up to that point was created for the upper-class theatregoers, polished and somewhat erudite, Osborne’s characters used slang, colloquialisms and the everyday simple language of the middle and lower classes.

As mentioned, Osborne had worked in the theatre when he was a young man as an actor and it was this experience that helped create in him that acute sense of stage and theatre. His works of drama managed to exploit those essential theatrical elements that helped portray man’s relationship with the society he lived in and with himself, through the interaction of characters and events.