Emerging from the vibrant tapestry of Iranian culture, Samira Ghafori and Anahita Ahmadi shape clay into powerful narratives of resilience and personal evolution.

The whirling hum of the spinning wheel, the rhythm of skilled hands modelling shapeless clay and the mesmerising transformation in the kiln: the world of pottery is one of patience, resilience and creativity. And within this sphere in Iran, two exceptional women, Samira Ghafori and Anahita Ahmadi, are shaping more than just clay.

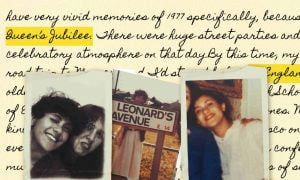

Samira, an artist who started young, had her destiny intertwined with pottery before she even knew it. Her early fascination with the craft was born out of playful experimentation that evolved into a lifelong commitment.

Today, she is not only an accomplished artist with a considerable social media following, but also an avid advocate for the art form. As she puts it, “Touching clay took me to a world where I enjoyed the process more than the outcome.”

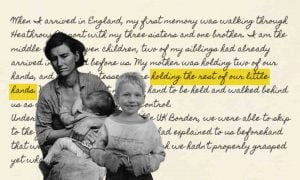

Anahita, on the other hand, navigated through a more labyrinthine path to pottery. A woman of many talents – from makeup artistry and mountain climbing to kickboxing and bodybuilding coaching – she grappled with societal pressures.

“Practising art for a woman was as worthless as playing with flowers in the backyard,” she reflects on the norms she defied. Yet, it was in this art form she found solace, turning to pottery as a healing balm following the death of her son. Now, through her Instagram channel, she shares her artworks with a growing audience.

Inspirations Carved in Clay

Inspiration can come from the most unsuspecting corners. “I can’t deny that observing artworks was inspiring for me,” Samira admits. The simple, often overlooked elements of nature and life captivate her. “The smallest things that others pass by easily preoccupy my mind for a long time. Simple things like tree trunks, birds, fish, human anatomy… engage me for hours, months, sometimes years.” Samira describes her artistic journey as a form of time travel, one where she can create her own timeline with what she has observed.

In contrast, Anahita’s inspiration springs from a more ‘domestic’ and personal source. After losing her son in 2019, Anahita turned to painting as a calming solace. “I spent several uninterrupted months drawing paintings,” she shares. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic stirred up her childhood interest in pottery, and with the world at a standstill, she turned to social media to learn from Japanese artists.

However, the most surprising of Anahita’s inspirations comes from her playful interaction with her pet cat, Bebber. “One of my biggest inspirations is my cat,” she fondly reveals. The playful feline had a knack for knocking over her pottery, a quirk that instead of causing annoyance, fuelled Anahita’s creativity. “One morning one of my works broke beautifully, and, now, my biggest inspiration for my recent works is from Bebber’s work.” Anahita is even planning an exhibition to showcase these “broken pieces,” a metaphor for the blows life can deal us, and the beauty that can still be created from them.

From nature’s subtleties to a playful cat’s spirit, Samira and Anahita find inspiration. Yet, in conservative Iranian society, it is often courage and resilience that carve their path, especially for many women.

Women Defying Iran’s Artistic Norms

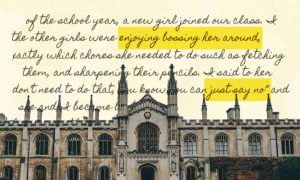

Despite the art scene being male-dominated, both artists have been resolute in their pursuit. Anahita, whose familial background was unsupportive of her artistic aspirations, shares her challenging journey.

“I was born in a family unfamiliar and estranged from art. In their view, a female artist was akin to a prostitute,” she says with frankness. “As a child, I was very passionate about painting and pottery, but practising this art as a woman was seen as worthless. For Anahita, being a single mother necessitated a focus on income, which led her to pursue a career in makeup.

Samira’s experience in the field also reflects a resilience and determination in the face of societal expectations. “This does not hold true for art,” she proclaims, rejecting any notion that gender could be a barrier in her artistic journey. “I am an Iranian woman, and no challenge is significant enough to even mention. If I decide to do something, I will do it, and neither society’s conditions nor anyone else can stop me.”

However, this resolve is part of a larger picture. “Despite more female pottery producers, the field remains largely male-dominated with insufficient support for women entrepreneurs,” Anahita points out. Yet, “… with the right support, women could confidently step into management roles, leading transformative changes in handicrafts”.

Imprint of Iranian Influence

Iran’s pottery tradition, steeped in rich history, serves as a broad canvas of inspiration, with each artist drawing uniquely from this cultural expanse. Samira, when discussing the influences on her work, regards the historical heritage of Iranian pottery with deep reverence. “Iranian pottery is incredibly rich,” she muses, expressing admiration for the ancient pottery from the archaeological sites of Sialk and Shush, which dates back to the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. “From north to south, my country is filled with remarkable pottery and ceramic works from every historical era.”

Anahita, too, finds a profound connection to her roots, but through a subtly different lens. She is captivated by the symbolism that graced the ancient vessels of her forebears.

“The simple or wavy lines are more than mere decorations; they symbolise life-giving streams and running water. Animal figures, be it goats, lambs, horses, cows, or birds, echo the harmonious coexistence between humans and domestic animals. The figure of the wild boar serves as a forewarning, a stark testament to the havoc it wreaked on ancient crops.” She further uncovers the profound resonance of celestial symbols like the snake and the sun, integral motifs that vividly painted the narratives of a long-gone era. “These varied patterns embody deep concepts, reflecting the perspectives, beliefs and rituals of our ancestors,” Anahita explains.

Yet, these symbols, while inspiring, are not directly observable in Anahita’s work. “Although these patterns inspire me, I don’t use them in my works,” she confesses. Instead, her pottery speaks a different language – the language of glaze. “The glaze reveals the mood and conditions within,” she admits.

Moulding Tomorrow’s Artists

“Iranian artists are under sanctions and cannot sell their works on the global market,” Samira candidly shares, highlighting a critical obstacle. Due to restrictions on global platforms like Etsy, Artsy, Shopify, Twitter and YouTube, Iranian artists face significant hurdles in showcasing their work to a worldwide audience.

As a result, “our pottery is leaning towards marketable works because artists need a good income to make ends meet,” Samira notes. Economic pressures often force artists to sacrifice their artistic vision for more marketable works. Samira expresses concern that this drive for marketability could suppress creativity and artistic integrity. “Many talented artists are forced to put aside their artistic visions,” she laments.

Anahita shares lessons from a life marked by resilience and exploration. Despite societal norms that dismissed her artistic aspirations, and balancing single motherhood with financial survival, she consistently found solace and expression in art. “Art stems from love and is the result of internal pressure, bursting into eruption,” she shares.

In response to a request for advice to emerging female artists in Iran, Samira’s humility is evident. “I’m too small a force to advise anyone,” she demurs. Nonetheless, her tenacity and steadfast dedication to her craft are inspirational in their own right. “Perhaps one day, I might serve as a role model, and others will come to understand that if we remain true to our spirit on our artistic journey, we can never truly lose.”

“I think we need to champion the recognition and encouragement of broader female participation across all domains,” says Anahita. “The presence of women in pottery has a history as old as human history itself, and women continue to play a significant role in this field, even if they remain largely unknown.”