Who makes graffiti? Street children who vandalise walls or mysterious artists whose works are worth millions? You may be surprised to know these three historical graffiti.

My cultural background and my personal tastes have always made my interests oscillate (also for the purposes of research and study) between figurative and written art. There is a topic that thanks to certain dynamics of realisation and conception, allows me to combine these two main fields of interest in a single analysis: graffiti. In fact, in this “category”, the testimonies on the wall and the writing often merge into a single genre.

In our contemporary cultural and artistic context, there is a dichotomy in the perception that we have about the world of graffiti. On the one hand, we imagine mysterious artists whose works are worth millions, on the other we perceive street children who vandalise walls. There is rarely a middle ground in this perception. I am hardly ever particularly struck by this artistic medium in its contemporary expression, no doubt due to my own limitations.

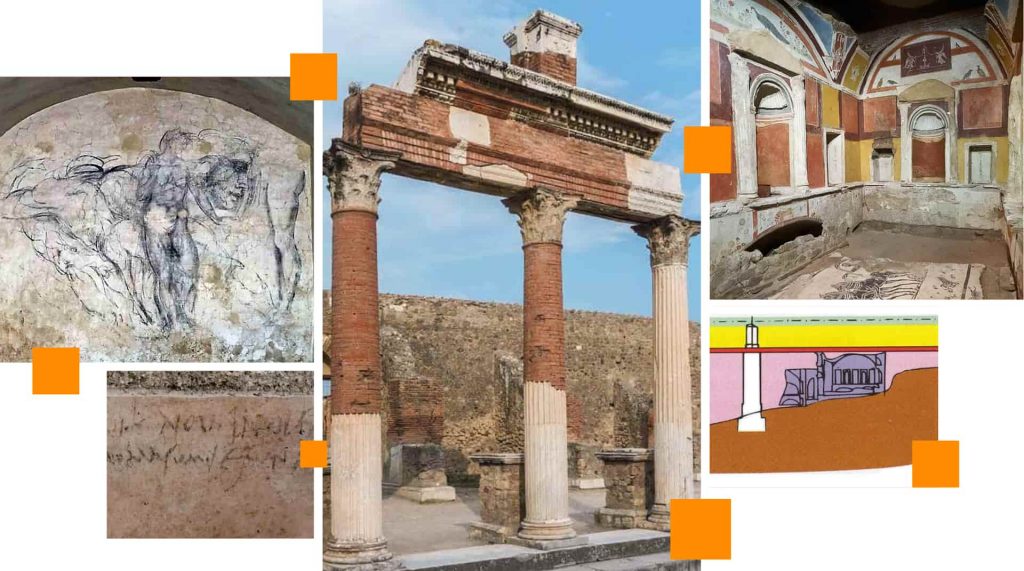

Graffiti at Vatican Necropolis

Yet the historical and artistic value of some graffiti is immense because it has proved to be fundamental both as an artistic testimony and as a historical documentary source. Thinking about it, graffiti is largely responsible for one of the most important choices of my life: my academic direction at university.

In fact, I decided on my course of study during the last year of secondary school when I had the opportunity of listening to the Italian archaeologist and epigraphist, Margherita Guarducci. She had the great merit of discovering the place of the burial of St. Peter in the area below the Vatican basilica. The discovery and identification of the saint’s relics took place in 1968, after many years of fruitless searches that jeopardised the credibility of the primacy of Rome in the Christian world.

The discovery was possible because Guarducci, as an attentive epigraphist, did not limit herself to an archaeological survey, but paid attention to testimonies that had, up to then, been ignored, namely the graffiti on a wall of the Vatican necropolis.

In an area known as wall G, there were many different graffiti with evident references to the figure of Peter, which even featured the letter P, the initial of the apostle’s name. This was created by fusing the key, a symbol that has always been associated with the apostle, to the graphic sign of the letter.

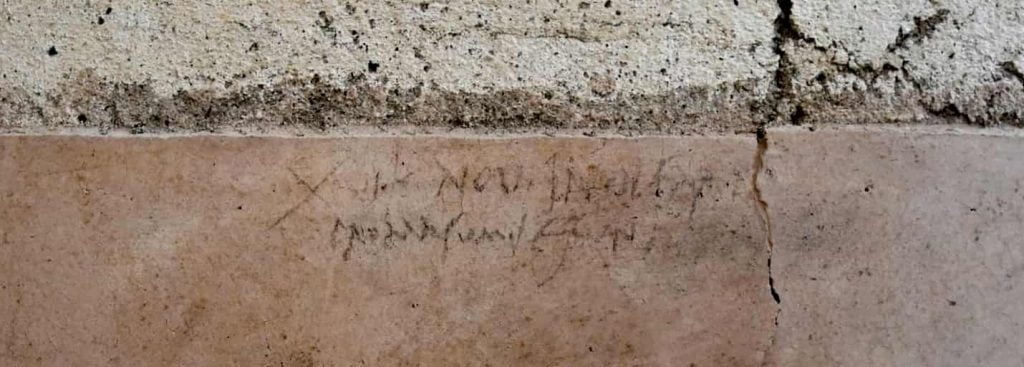

Apart from the repetition of this initial, the graffiti that most of all had the merit of leading to the archaeological discovery, was the phrase ‘PETR … ENI’ which could be translated both as Peter is here, or as Peter in peace (Petros en irene).

Similar writing is not only present at the tomb of Peter, but is generally found at the burials of various saints. Often graffiti was engraved on the walls of cemetery areas, both to indicate the very presence of the saints buried there, and to testify to the individual faithful who had prayed in that sacred spot.

Graffiti at Domus Celimontana

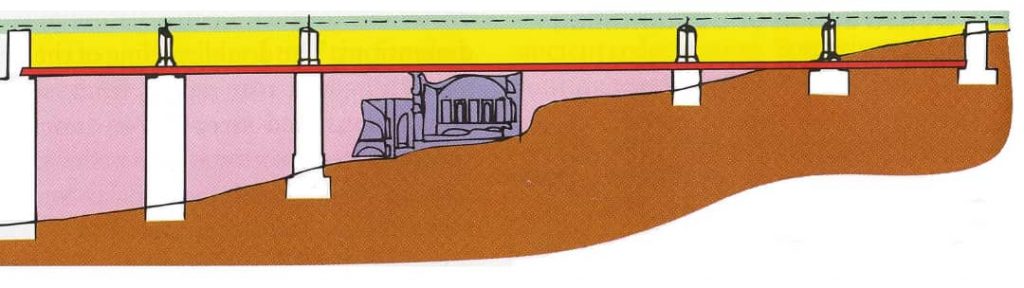

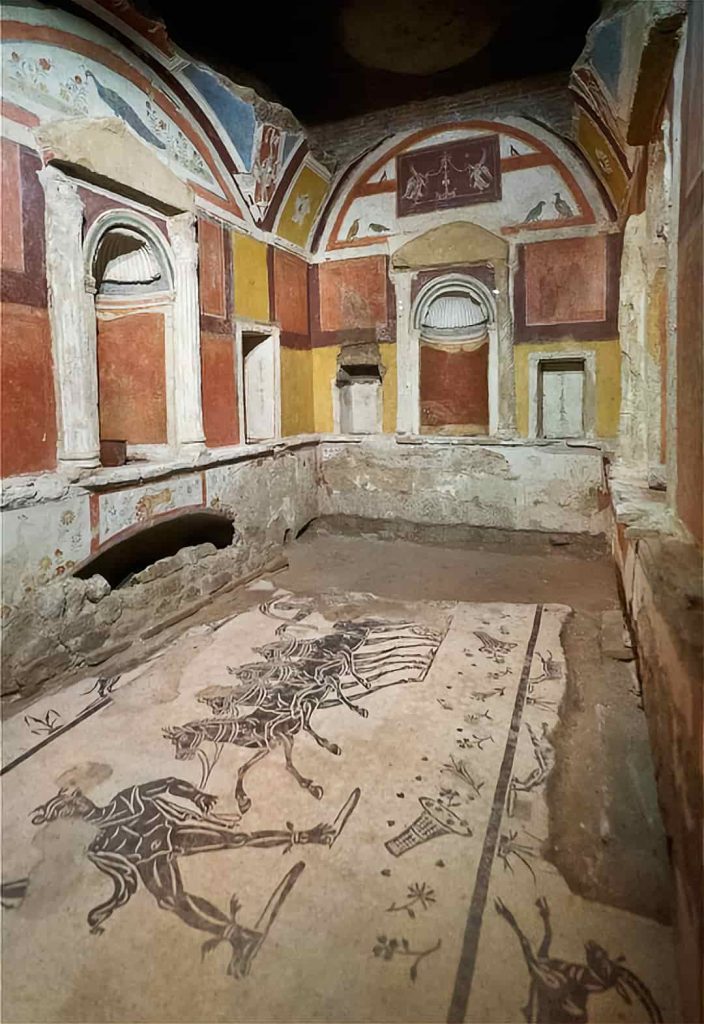

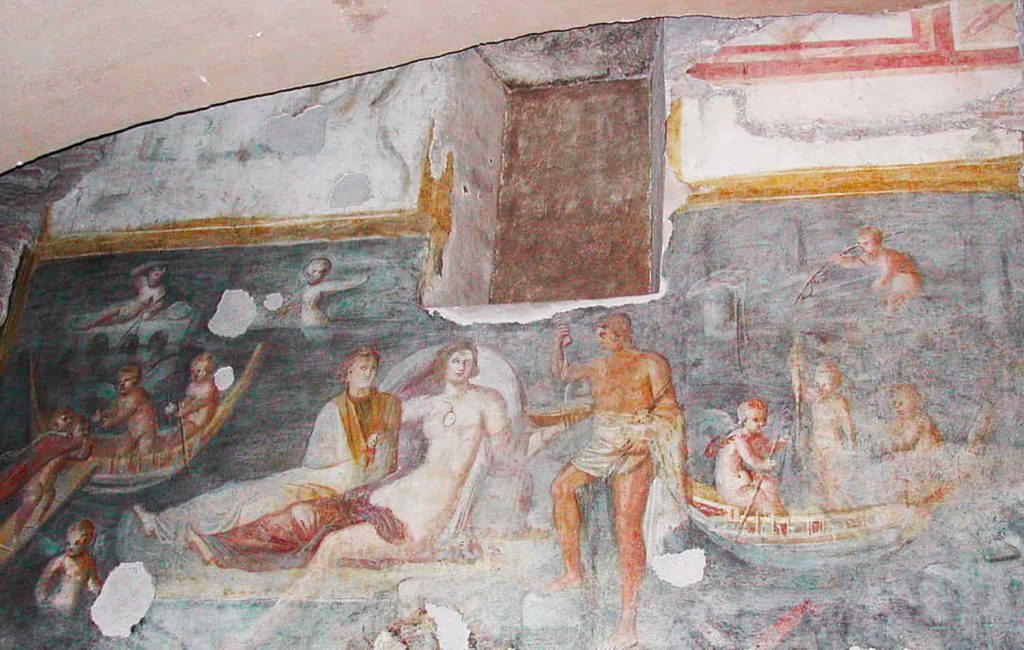

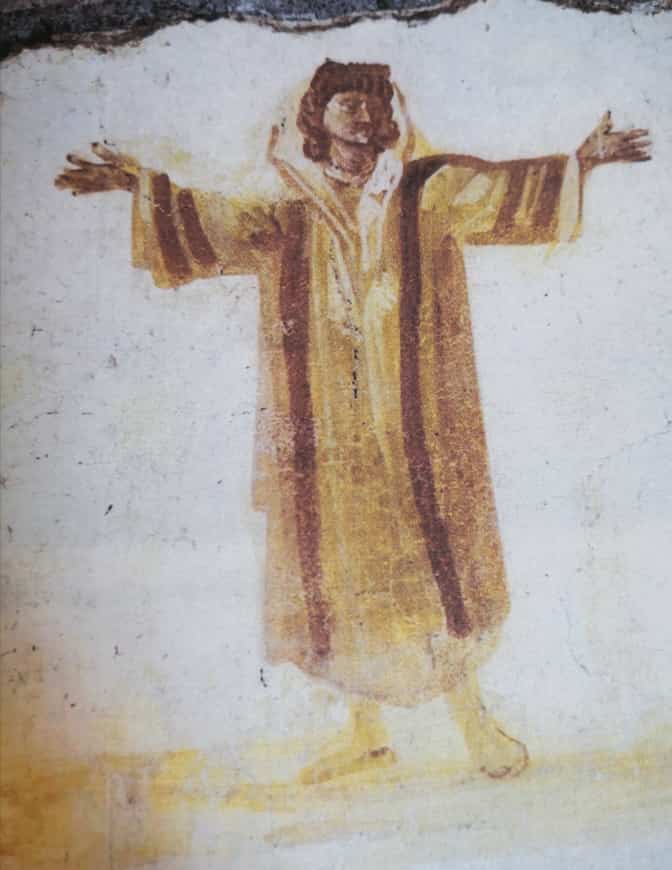

As I progressed in my training, I often encountered and examined the world of graffiti. For example, while researching my degree thesis on the Celimontana house of Saints John and Paul in Rome, I was able to delve into a study of the graffiti preserved inside the Roman house discovered beneath the church.

In the Celio house, the walls contain various carvings. Some simply bear the name of the faithful who frequented the house after the fourth century, such as Rufina and Ursa. Others are verbs typically used by the early Christian community, like orate and vivas.

Near the Hall of the Praying Person, also in the Domus del Celio, we find fairly common religious graffiti depicting a boat, which symbolises the soul. Other graffiti can be found along the stairs leading to the cell of the house. These were of great help in identifying the place where the two martyrs, John and Paul, were buried.

Along the wall that runs along the stairs of the aforementioned cell (confessio), some faithful of the past had drawn notches side by side to testify to their presence in the place of worship. The signs thus engraved testify not only to a simple presence, but to the repetition of the pilgrimage of the faithful to obtain with greater certainty the grace requested of the venerated saint, or to obtain forgiveness for sins committed.

Next to these graffiti that testify to the historical and anthropological transformation of the period of early Christianity, there are others etched by pagans who looked at and lived this transformation with hostility and distrust.

The Titulus as a safe haven – Case Romane del Celio

Among the many that belong to this context, it is impossible not to name the graffiti known as the ‘Blasphemous Crucifix of the Palatine’ with Christ represented with the body of a man but the head of a donkey, or the lesser-known graffiti found in the taberna of the villa of Domitia Lucilla in Laterano, in which a fishbone with a human head represents a clear and ironic reference to one of the most ancient Christian symbols: the fish.

Graffit at Pompeii and Herculaneum

What we have examined so far highlights graffiti as witnesses of historical passages or moments in time. However, these scratches on the wall are by no means isolated historical sources. They fall within the meaning of “alternative documentary sources” because they amplify the official historical evidence reported by contemporary historians.

On the other hand, graffiti can be raised to primary documents when the less durable ones have been destroyed, as in the case of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The events experienced in these cities, victims of the destructive fury of the eruption of Vesuvius, have been admirably reconstructed thanks to the conservation of many testimonies that tell us about the life of the cities before the eruption.

We are talking about archaeological testimonies and written accounts, recorded not on paper but right on the walls of the homes that were involved in the eruption. This is because what was the main cause of the demise of these cities, paradoxically, was also the cause of their survival over time.

Thanks to the perfect conservation of the finds encapsulated by the blanket of ash and lapilli, the excavations of the areas adjacent to Vesuvius have given us a faithful glimpse of the life of the centres before the eruption of 79 AD. All the findings that took place in this excavation area allow us to understand the daily habits of the period, many of which are told in the numerous writings on the walls of the city buildings.

Reading these graffiti is really interesting from both an anthropological and historical point of view, because they enrich our perception of daily life within Roman cities without the filter of official stories.

Among the many secrets that the inhabitants of the past have told us by writing them on the walls of the cities, what has turned out to be fundamental for the purposes of study and research is an inscription that was found in the Regio V of Pompeii.

This inscription reads: “XVI ( ante) K(alendas) Nov(emberes) in (d)ulsit”; in other words: “On October 17 he indulged in food in an immoderate way”.

This date recorded in the graffiti speaks of the sixteenth day before the Kalends of November, effectively shifting the date of the eruption from 24 August to 24 October 79 AD. Historians, while still expressing themselves with caution, have begun to evaluate this until recently unknown graffiti with particular historical interest.

What has been said so far does not always include the name of the author of the writings or drawings and, when it does, it does not greatly enrich our knowledge of the person who hides behind the graffiti.

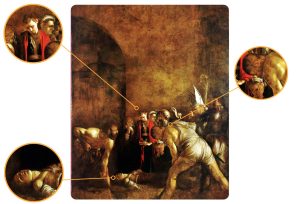

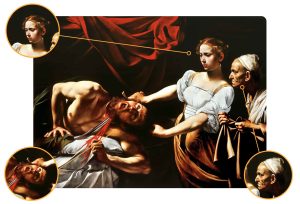

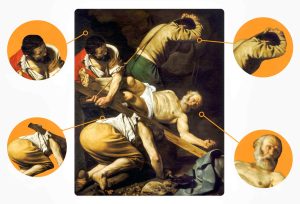

Graffiti at Medici Chapels (Michelangelo)

Taking a considerable time jump compared to the facts just mentioned, however, we find a series of graffiti that enrich our knowledge of a decidedly well-known character. I refer to those preserved in the area below the Medici Chapels in Florence, more precisely inside a secret room whose access was hidden from the outside, which tells us about an almost unknown aspect of Michelangelo.

In this environment, in 1530, the artist hid for about three months to escape the revenge of the Medici family who were in exile after a popular revolt during which Michelangelo had sided with the rebels. In this narrow space, (we are talking about a small room of seven metres by two), Michelangelo filled his time with art rather than with solitude, creating charcoal drawings reproducing new interpretations of old works and conceiving new ones.

On the walls, we find a head of Laocoon, a reinterpretation of Leda and David, bodies found on the walls of the Sistine Chapel and probably a self-portrait of the artist, who is folded in on himself, certainly challenged by this forced stay.

Not all scholars agree in attributing these drawings to Buonarroti, but the type of stroke, the natural pose and the sensation of movement of the body of the subjects drawn on the walls make me lean towards a Michelangelo’s attribution of graffiti. The need to communicate and express oneself, which is the basis of every “traditional” work of art, is also the basis of graffiti that testify to a life, told through the only means available to their author.

Notwithstanding that I am against the censorship of thought and that I believe that every expression of the self deserves space and attention, I cannot understand some nuances of metropolitan graffiti, though I am perfectly aware of the particular nature of many graffiti of the past.

Pompeii itself has given us strong and colourful attacks, for personal or political reasons, against some people of the city. It has even presented us the rates of brothels, but next to these more immediate and impetuous manifestations of human life, it has also transmitted writings that are real jewels. I refer to phrases created to disclose and celebrate feelings through carefully chosen words as if they were poetry.

My perplexity about some graffiti is not the result of false and sterile respectability. I firmly believe that everyone must be aware that what we express through drawings or graphic signs reveals nothing less than our true and intimate nature. We must therefore choose with deep awareness what we want to convey about ourselves and the means through which to express it, remembering that… ‘Scripta Manent’.