In this article, we will explore the three UN conventions that are designed to protect the laws of our seas: the UNCLOS, the ITLOS and ISA.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

In 1982, the third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted after nearly 26 years of attempts to replace the archaic “freedom of the seas” concept, which dated all the way back to the 17th century. The convention came into force in 1994 and established rules governing the uses of the oceans and their resources. Essentially encapsulating traditional rules for ocean use in a single instrument while also introducing new legal concepts, as well as addressing new concerns that arose with modern times. Some notable developments ushered by the convention include:

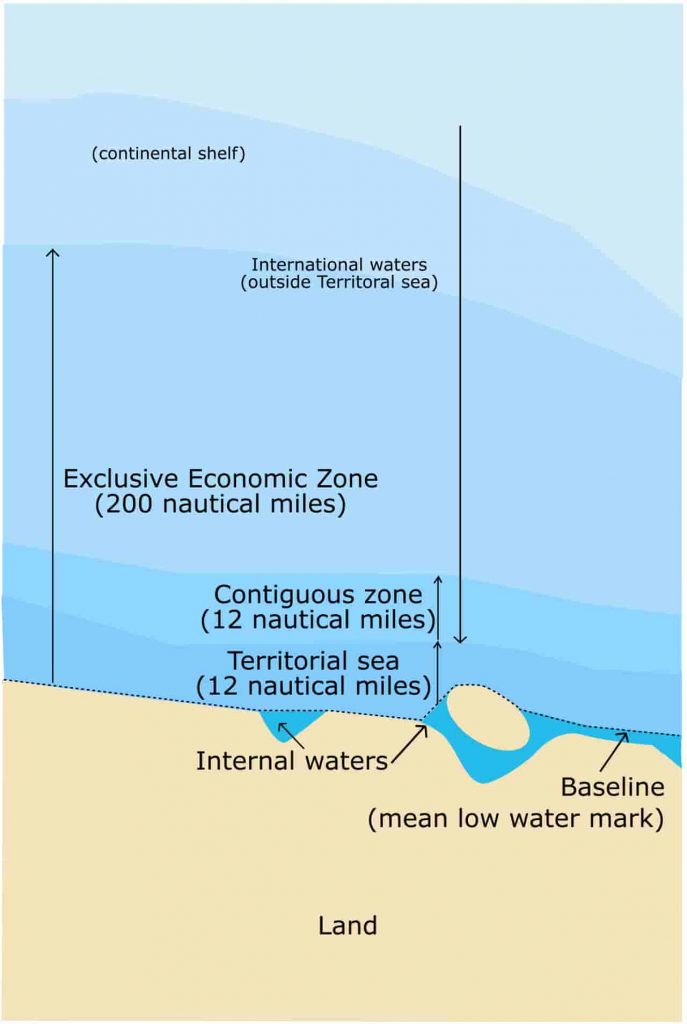

- The formation of 200 nautical miles of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) over which independent nationstates have the sovereign legal power to explore and utilise the sea.

- Anything beyond the EEZs is defined as the “high seas” and classified as the “common heritage of humankind”. (See the section about ISA).

- Introducing a 12-nautical-mile zone (about 22 Km) around coastal states, which the convention sanctioned as “territorial seas”. Within these territorial seas “innocent passage” of other ships including warships are allowed.

- Establishing a dispute resolution mechanism for nationstates (we will discuss this shortly in the section about ITLOS).

Of course, one can easily claim that the convention complicated, rather than simplified, maritime law and security. The introduction of the EEZs, one can argue, is certainly one of the complications of the convention.

Naturally, oceans don’t align with arbitrary borders that nations draw, in the case of overlapping EEZs, UNCLOS simply leaves the matter to be resolved by the nationstates themselves. Moreover, the EEZs end up favouring countries with the most coastal borders, such as the UK, France, Indonesia, Brazil and Australia. Many also argue that the division of the sea has no proportionality to the population of the country. This has left a country like New Zealand with a population of around five million with 4.1 million sq km while China, which has a population of 1.3 billion, with around 900,000 sq km.

At least most nationstates are signed to the convention, right? You will be glad to know that the majority of the UN’s member states have signed onto UNCLOS. To date, the convention has been signed by 189 UN member states plus, the UN Observer state Palestine, the Cook Islands, Niue and the European Union, so 193 signatories overall.

Most large military powers, including the permanent members of the UN Security Council – besides one, which has not yet ratified it – are signatories to the convention. I know what you may be thinking: It’s the same country that claims ownership over everything within its “nine-dash line”, stretching from Taiwan to Malaysia. No, it’s not China, but rather the United States.

Although the US was pivotal in establishing the convention, to date, the country’s senate has refused to vote for the US to ratify it. Many Republicans continue arguing that UNCLOS threatens their “national security” by interfering with US’ ocean military operations and hindering seabed mining corporations by imposing “unnecessary” environmental regulations. This leaves the United States, without the moral authority when it comes to lecturing countries, like China, regarding the laws of the sea. Besides the US, there are also some countries that have not signed, nor ratified the agreement. Some of these are: Turkey, Israel, Kazakhstan, Peru, The Holy See, Syria, Tajikistan and Venezuela.

Who supervises the convention and what powers does it have? UNCLOS is not overseen by the United Nations Secretary-General. Supervision of the convention falls under the job description of the Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS) of the Office of Legal Affairs of the United Nations. Regarding what powers the convention realistically has, UNCLOS does have a tribunal, but that’s a whole other can of worms. Let’s open it, shall we?

The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS)

Created and established by UNCLOS in 1994, The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea consists of 21 judges selected through a secret ballot by participating states. Binding settlements through an arbitration panel or an international court is one of a number of procedures that signatories are presented with when attempting to resolve competitive interstate issues. Some of the other mechanisms for resolving differences include:

- Bilateral negotiations,

- Non-binding third party settlements such as good offices and conciliation,

- Mediation.

Throughout its history, ITLOS ruled on several high-profile cases. One of these relates to the disputed territory of Diego Garcia.

The UK versus Mauritius case

In spite of the fact that the Chagos Archipelago received its independence in 1965, the UK refused to accept the decision. In true colonial spirit, it proceeded to deport all of the 1,500 residents of its largest island, Diego Garcia and set up a US/UK military base. The UK stripped the island of its name and called it British Indian Ocean Territory. In 2019, the ITLOS, later backed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the UN General Assembly ruled that: “The United Kingdom was under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago”. To no one’s surprise, the UK government immediately made it clear that it would disregard the verdict.

The Netherlands versus the Russian Federation

Another story relates to the Arctic Sunrise, which was the name of a vessel operated by Greenpeace. In 2013, after it became clear that Gazprom, a Russian state-owned company, who was in charge of the oil extraction in the area, was not prepared to deal with a spill linked with oil extraction, Greenpeace and the Arctic Sunrise staged protests against the Prirazlomnaya oil rig. However, the situation escalated after three crew members of the vessel attempted to board the platform. The Russian coast guard responded by seizing control of the ship and detaining all the crew. All 30 activists were initially charged with piracy, which could have carried a sentence of fifteen years of imprisonment, however, the charges were later downgraded to hooliganism, which carried a lesser sentence.

The Netherlands subsequently brought the case to the ITLOS demanding the immediate release of the activists and the Arctic Sunrise. Even though the Netherlands’ claim was supported by fact and law; Russia refused to participate in the tribunal as it saw the matter as one relating to its own internal law. On November 22nd, the ITLOS decision dealt a blow to the Russian Federation, ordering Moscow to release the Arctic Sunrise and its activists. The Russian Federation refused to follow the verdict, another hammer blow to the authority of the court. Nevertheless, the crew and the Arctic Sunrise did end up being pardoned during the celebration of the 20th anniversary of Russia’s post-Soviet constitution.

The Philippines versus China case

The Arctic Sunrise Case shares a lot of similarities with the case of Philippines versus China, who claims 90% of the South China Sea. The tribunal’s Arctic Sunrise decision was closely watched and scrutinised by China’s leaders who also refused to participate in an UNCLOS challenge brought by the Philippines over maritime claims in the South China Sea.

The ITLOS ruled that “although Chinese navigators and fishermen, as well as those of other states, had historically made use of the islands in the South China Sea, there was no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or their resources.” The tribunal concluded that there was no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources within the sea areas falling within the ‘nine-dash line’. In 2016, China’s government refused the tribunal’s verdict.

You may be sensing a pattern by now. As you can see, within the last decade alone, three of the signatories to the convention refused to accept the ITLOS ruling. This exposes the weakness of the Court in as much as it depends on goodwill and the willingness of the parties involved to comply with the rulings.

This does not mean that the court is useless. The ITLOS does have a number of successes, but this is only because both parties decided to accept the court’s jurisdiction and compromise. The United Nations is no stranger to kangaroo courts and decisions at the ITLOS, the ICC and even the ICJ will continue to be disregarded as long as there is no mechanism to enforce international law. Well, what can be done? Here are some solutions toward comprehensive global justice.

Now, how is the United Nations prepared to save our oceans from the greed of corporations and what does UNCLOS exactly mean when it says that “high seas” are classified as the “common heritage of humankind”?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA)

Technically made up of the EU and 167 countries, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) was established by UNCLOS itself in order to regulate, organise and control through licences and contracts with companies and governments, all mining explorations.

Remember, according to UNCLOS, each country could only explore and exploit an area within 200 nautical miles of its coasts to mine. If a country, corporation, association or even private individual wants to exploit the high seas, or as the convention calls it “humanity’s common heritage” they need to ask for a permit.

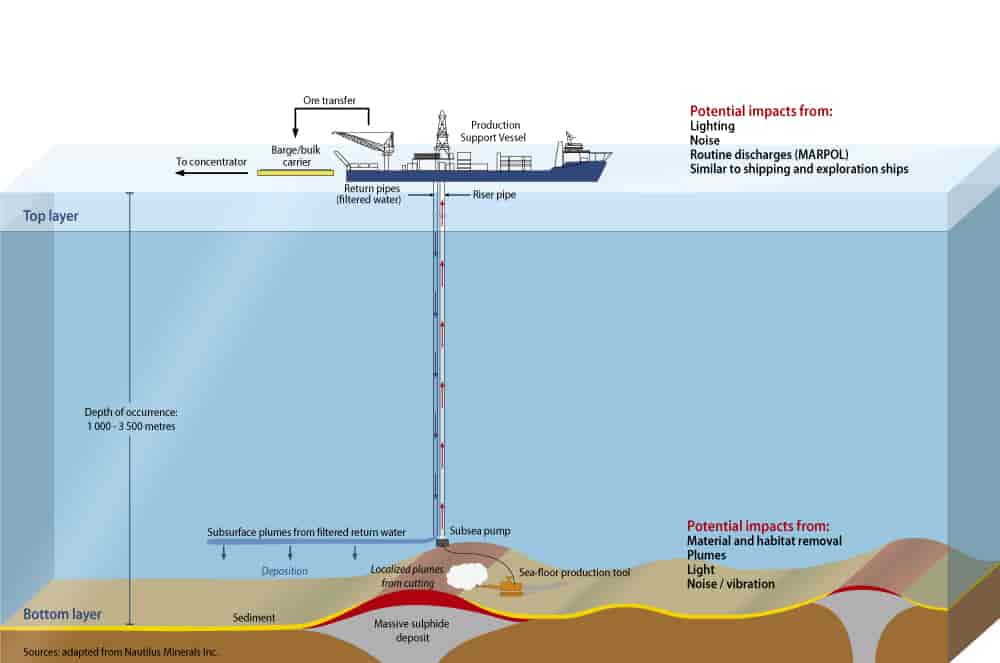

This was the case with Nauru and The Metals Company (TMC). Earlier this year, scientists and environmentalists warned of a massive ecological tragedy that could result from planned deep-sea mining in Nauru, where the Nauru Ocean Resources, a subsidiary of the Canadian firm TMC, wanted to mine the nodule-rich region.

But all should be well. Isn’t the regulatory body supposed to protect our seas, you know, like the police would? Well, sadly, more like corrupt police.

There are no specialised environmental or scientific evaluation groups vetting new contract applications. Once an application is sent to ISA, it is processed by the body’s Legal and Technical Commission (LTC), which consists of only 30 members, most of whom work directly for contractors with deep sea mining projects. But surely they can’t just approve every application: Get this: to date, the body has a 100% record of approving cases. Oh, did I forget to mention that each application costs half a million dollars?

When the General Assembly of the UN approved the budget for the body, it stated that the shared heritage should be dealt inline with “the growing reliance on market principles”. This should have been the first giveaway: since when has the market cared about humanity’s shared heritage?

Chasing the unassuming treasures under the sea may seem attractive, but being the kind of self-interested pieces of garbage we humans are, we rarely think about the consequences of our actions and how they affect our environment. The concept of mining the sea is not an issue by itself. After all, getting our nodules, which we use for our battery-powered electronics, out of the sea, could be more sustainable than onshore mining. Fishing our resources out of the deep sea could potentially solve climate change.

The problem here is that we are quite literally dealing with uncharted waters. While corporations claim that they are meeting the need to transition to a more sustainable economy, many scientists and activists worry about the irreversible impact deep sea mining could have on our ecosystem.

Luckily, the World Congress of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has, through a non-binding vote, declared that it is attempting to ban deep sea mining. It also plans to appeal against the Nauru and TMC case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. To whom? Oh!

As yet, there is no proper Global Ocean Treaty that aims to seriously protect the “common heritage” of the High Seas. Those that do exist, really do anything but protect this heritage. There is no doubt that there are many well-intentioned people working for the UN, but most regulations regarding our seas are skewed towards a flexible or soft treaty that gives priority to economic exploitation over environmental concerns.