Empowering continents and ensuring lasting peace – a case for permanent continental members at the UN Security Council

Perhaps the greatest impediment to world peace is the United Nations Security Council itself. This is felt by the power of the mighty veto held by each of the five permanent members.

The image of the Security Council is that of a “club of superpowers” each prioritising its own national interests over the other. In the rule of the jungle, realities of realpolitik assume total precedence where “might is right decision theory” rules supremely.

This has reduced the rule of international law to arbitrary geopolitical gerrymandering. This is the legacy of the Security Council, but can it be saved, let alone reformed, to make a better world possible?

History of Security Council Reform

Reform of the Security Council was not truly prioritised until the end of the Cold War as the international community transitioned from a bipolar world to a multipolar one. The most significant push for reform began in 1992 under the tenure of Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali by proposing an expansion of the Security Council’s membership.

Beginning in 1996, the Italian sponsored “Uniting for Consensus,” also known as the Coffee Club, proposed adding new permanent members of G4 nations to include Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan to the Security Council.

Little time was wasted to counteract this proposition by non-G4 nations. Under Islamabad’s leadership, Pakistan would replace India, Mexico, Columbia, and Argentina were to replace Brazil, and Japan would be exchanged for South Korea.

This was proposed to break the Global North’s monopoly of power on the Security Council by affording “deferential preferentiality” to rapidly developing nations in the Global South.

In 2005, Kofi Annan proposed his “2005 Plan” to increase permanent Security Council membership to 24 nations including the existing club of five.

As an adherent to Annan’s philosophy on Security Council expansion, Ban Ki-Moon acknowledged the need to increase membership as something long overdue to better reflect the multipolar diversity of the world during his tenure as secretary-general.

This has given rise to Security Council outsiders questioning the “propositional feasibility” of such solutions against the backdrop of our increasingly estranged multipolar reality.

Do they go far enough or are they simply uninspired solutions designed to tease and appease more increasingly assertive nations eager to even the geopolitical playing field?

Security Council alternatives

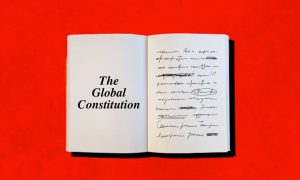

Why not explore the “supranational possibilities” for geopolitical union as defined by continent?

Instead of five permanent members defined by national interest, there would be eight permanent continental members. A new and reformed Security Council would be represented by continental blocs turned supranational unions for purposes of maximising equilibrium in the actual distribution of international law.

This project would be hatched under a centralising focus to deny the possibility of war or military aggression between nations.

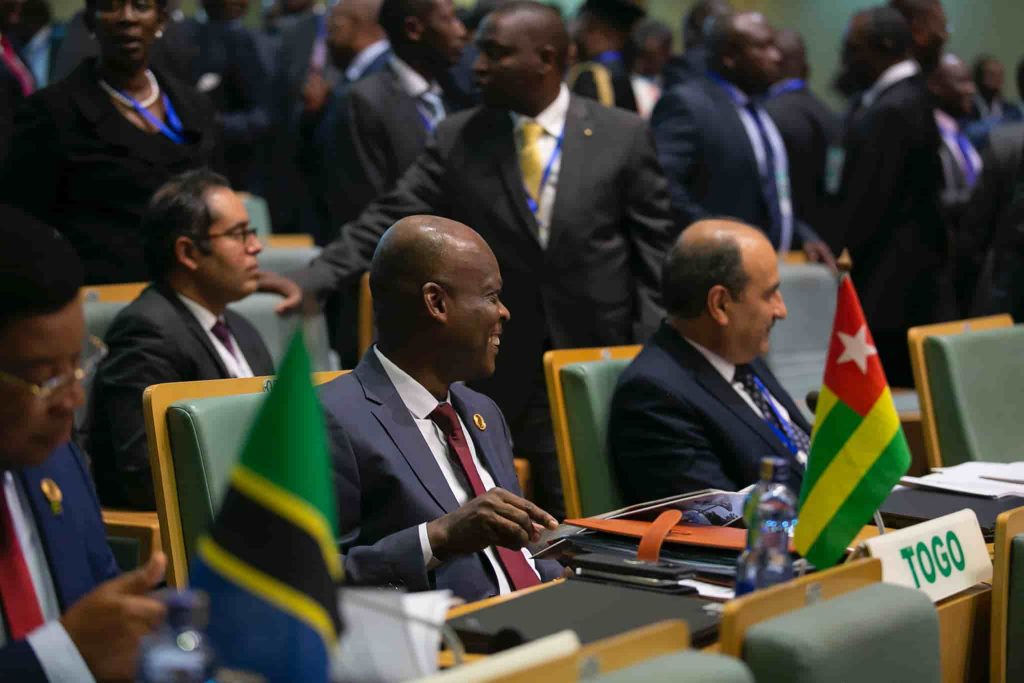

The inspiration supporting the architecture for “supranational continentalisation” is derived from the European and African Unions respectively in addition to the Union of South American Nations.

Considering the vast ethnologic diversity and geographic enormity of Asia, two supranational unions would be required to represent the continent explaining why a renewed and restored Security Council would have eight permanent members.

At present, the Asian Cooperative Dialogue and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations are Asia’s continental equivalents to supranational unions.

Although arguably counterintuitive, Antarctica would be represented on a rotating four-year basis by nations with the greatest foreign assets on the continent. This would be measured by metrics of scientific research, economic activity, and military defense as defined by spheres of influence.

Considering most nations active in Antarctica are already world powers, the supranational body overseeing the continent would work separate from their counterparts already on the Security Council.

Civilianise governance instead of militarising it

Rather, they would be represented by a leading scientific agency specialising in Antarctica from the relevant national superpower holding the rotating seat to diversify interests at the council to avoid overlap between more traditional spheres of diplomatic and military influence.

For example, Washington could entrust the United States Arctic Research Commission to represent Antarctica under such “associative supranational premises.”

The thinking is to inspire a diversification in supranational governance in underrepresented and marginalised areas to effectively civilianise governance instead of militarising it.

This experiment can determine if a separation of “supranational powers” is possible when applied differentially beyond foreign policy maxims at the Security Council.

By recognising supranational organisations like the European Union as traditional state actors, while serving as permanent members of the Security Council simultaneously, the next great evolution in international relations can be achieved delivering a more representative and balanced world of global governance.

Nonetheless, it may prove necessary to reinvent the wheel considering controversies and low confidence in existing supranational organisations like the African Union.

This new existential basis for the Security Council can possibly exceed capacities and known capabilities of pre-existing supranational organisations designed primarily to be “continent centric.”

Thus, propositions for a potential “African Geopolitical Union” can be considered as a templated standard for such an experiment made in the name of supranationalism at a renewed Security Council for a restored United Nations.

As always, the task of sourcing leadership for such supranational organisations will prove challenging if not preventative or downright exhaustive, but the end results may definitely prove worth it in the long run.