Citizenship is a construct, our primary duty is to humankind

Our silence is pernicious and yet we seem to not care; not when caring can threaten the comfort zones we have become so used to. Here are five points that will shed some light on the issue of migration.

The migrant problem

Anyone who has studied their history will know that migrations are what shaped the world as we know it today, both politically and ethnically. At times these migrations were peaceful. Often, they were predatory. At times they were gradual, spreading like an oil stain; often, they were sudden and quite alien, like a frenzied splash from a Jackson Pollock paintbrush. At times the end result was growth and a fusion of cultures; often, it was genocide. So we built walls of brick and paper to keep the undesirables out. Most of us belonged to those undesirables once, but that was a long time ago.

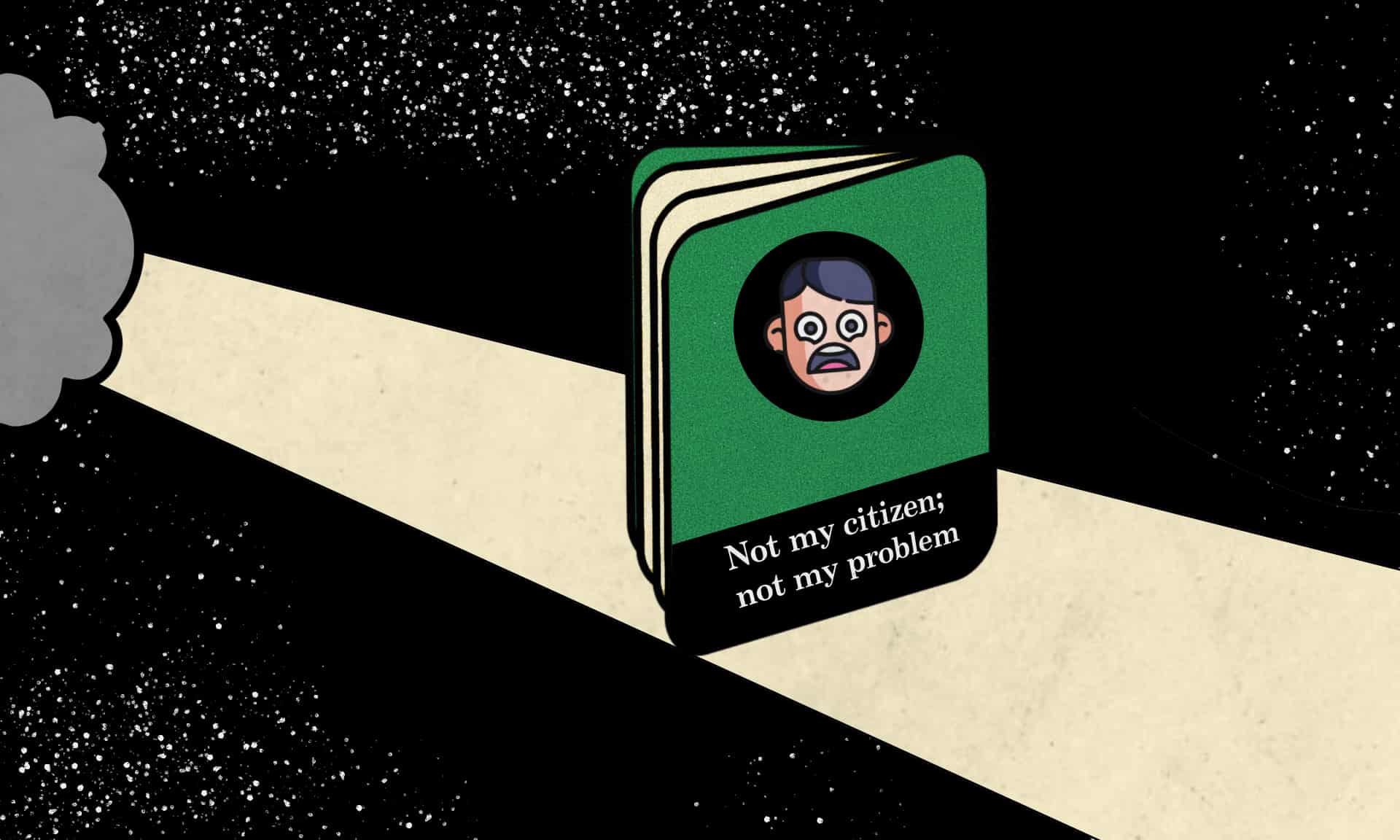

We are settled and comfortable now. The greedy with their ravaging hordes are not so much the problem any more. The main problem stems from the poor, persecuted and dispossessed and they are easy enough to keep at bay. Moreover, the general consensus is precisely that: “keep them out”. Indeed, the very countries that are most hostile to migrants and refugees are, more often than not, the very same that exploited or destabilised the lands that these people are fleeing from in the first place; but that too is history.

“We cannot afford to let these people destabilise our countries. The risk is too great. Let them rot in refugee camps. Let them drown in their desperate attempts to reach safer shores. Let them die of exposure and hunger at closed borders. Our duty is to our citizens, so damn them!”

Surely not? Surely we cannot be that cynical and heartless? The sad reality is that we are. Qui tacet, consentire videtur. Those hateful words above can only be heard in silence and the few who utter them are indebted to our silence, which is what amplifies the contempt and emboldens it. But should you have any doubts, just look to the ballot box.

See how gingerly moderate politicians have to tread to avoid any show of concern for migrants or refugees for fear of losing votes, while the right can stomp and demonise them quite brazenly. Most of us know how pernicious our silence is. The problem is that most do not care; not when caring can threaten the comfort zones we have become so used to.

More angles than a rhombicosidodecahedron

The issues surrounding the migration and refugee problem are countless and anyone who would make you believe otherwise is a fool or a liar.

The economic impact of migration, for instance, has so many variables, ranging from the economic and social makeup of host countries to the age, skills and trauma of the immigrant or refugee. In between, we find administration procedures, attitudes, culture clashes and a host of variables that makes evaluating overall impact anything but an exact science; while the pandemic certainly has not made the situation any easier to assess.

Tempting as it may be, however, unravelling the minutiae of the migrant problem is not necessarily how we will find the solutions we are looking for. I would like to focus on five points relating to migration that I hope will shed some light on the issue, starting with some of the causes and moving on to some of the solutions.

1. Triggers to migration

When grandmama fell off the boat… Very nearly taking note of migration

Personal triggers, like boredom, curiosity and not fitting in, are singular events that do not rattle the various establishments of the “civilised” world, though they can easily result in individual hardships. A gay man committing suicide because he was barred from moving to another country, while having been victimised at home, is projected as tough luck, rather than a symptom of a flawed international system.

These people are not considered in the statistics. However, 82.4 million people are. That is the number of forcibly displaced people in 2020 according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). When masses are involved, the issues are not that easily swept under the carpet, but even here, much will depend on how we define “forcibly”.

People fleeing war, civil unrest, famine, natural disasters and catastrophes of a similar magnitude easily qualify. Those hoping to escape oppressive regimes, debilitating corruption, shrinking economies and limited resources generally do not. Of course, this does not mean that the people who are “lucky” enough to be defined as legitimately displaced are therefore party to a host of benefits from the international community that would make their lives bearable. It just means that those that are not are even less likely to receive help and are often treated with even more contempt.

2. Nipping the problem in the bud

The best help would be to aim at the source of the problem so that people would not feel the need to flee their territories en masse in the first place. When the problems are natural, this should not be that difficult because the world as a whole does have enough resources to cover the needs of humanity and it could do so many times over if we managed our production and consumption more wisely; by getting rid of all the waste that is linked to the meat and dairy industries, for instance.

Building a more equitable world and sustaining it, even in the face of disasters, is well within our possibilities. Of course, this may not be the case for much longer if we keep abusing the planet at the current rate.

The doomsday clock is only 100 seconds to midnight for a reason.

Still, in this scenario, we will all need to be displaced, only that there will not be anywhere for us to go. When the problems are political, however, the answers are much harder to find, particularly since superpowers are often at the root of the problems to start with. The tragedies in Syria, Yemen, Myanmar and Palestine, for instance, are all tied to the machinations of one superpower or another that are exacerbating the situation. Nevertheless, countries do not necessarily need an outside force to incite them to self-destruct or become a nightmare for a proportion of their citizens.

The governments in Iran and Venezuela, for instance, have been managing to implode quite nicely without the need of external forces, which of course still give a helping hand. Sometimes, it is not even the governments, but the narrowmindedness of the majority of the population itself that is the problem.

Theocracies spring to mind, but democracies can be quite as bad, particularly when people vote in right wing extremists that persecute minorities. Here, the long-term solution to these problems is an international world order such as the one UN-aligned proposes that will address these issues. In the meantime, however, as much international pressure needs to be exerted in order to minimise the abuse. The obvious broker here would be the United Nations, but as I have made abundantly clear in my book, Unravelling the United Nations, the UN has failed in its mandate. So, each nation, or block of nations, should do what can be done to pressure countries to comply with moral standards that respect human rights.

3. Getting rid of the refugee camps

As things stand, there is a need for temporary stations, but turning these into permanent camps is as bad as sentencing people to life imprisonment or forcing them to spend the rest of their lives in the transit lounge of an airport. This is the opposite of help. It is, in fact, preventing people from moving on and helping themselves.

Writing for The Gordian, Jihan Khaled Alassad, a Syrian refugee living in a camp in Southern Lebanon, has covered many of the hardships refugees face. In one of her journals, she states:

“To live in a camp means that all your days are the same, as if the hour hand is fixed in its place and refuses to move. Nothing changes except the weather conditions around us…

There is nothing different in my days, repeating themselves to tell me that I will remain a hostage to their misery and pain.”

No one should be forced to live in a camp for more than a few months, weeks is bad enough. The refugee camp is half a bridge; a jetty sticking out of a flat earth over an abyss. It is not a sign of our evolution, but a testimony to our selfishness and ignorance.

4. The other half of the bridge

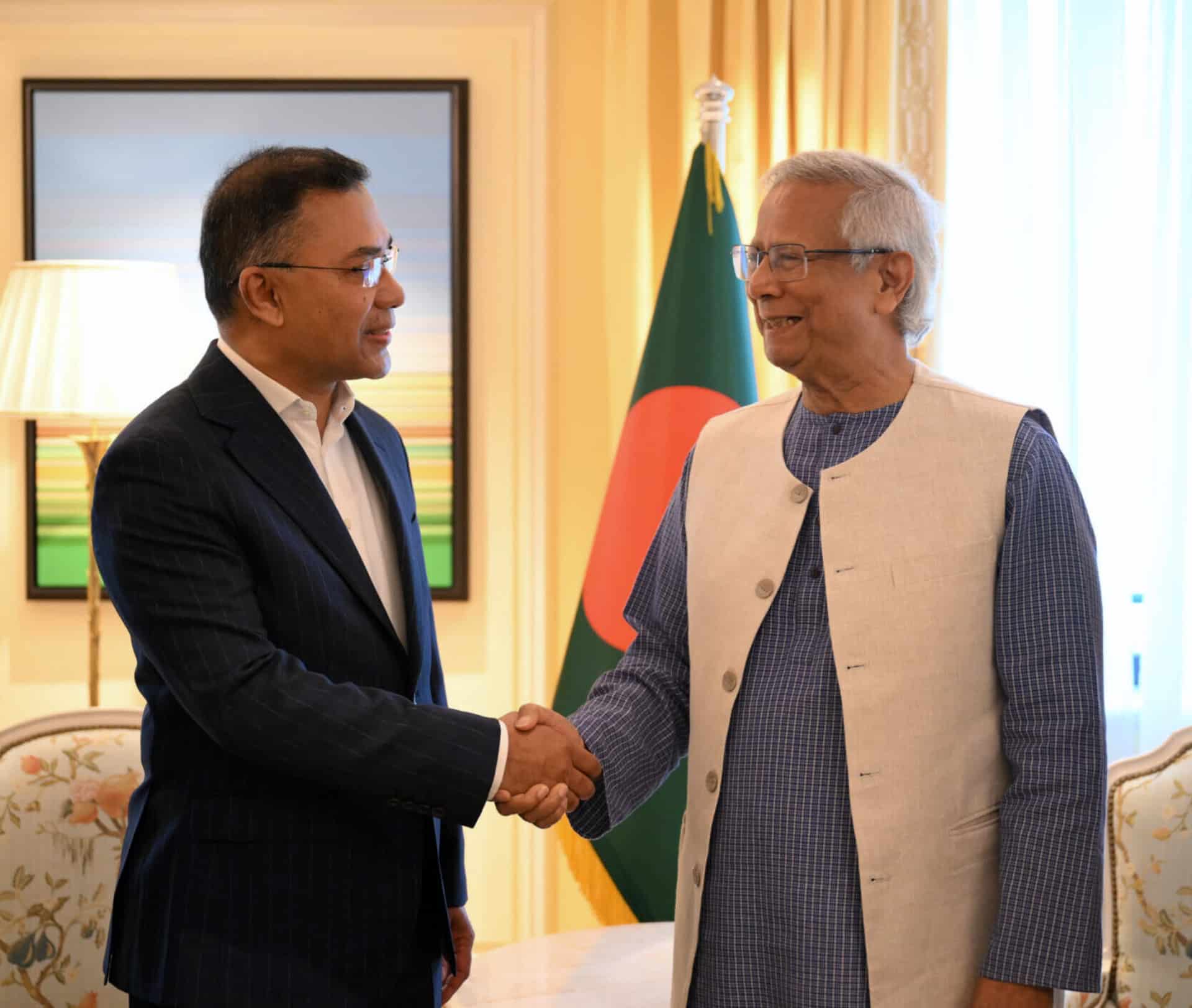

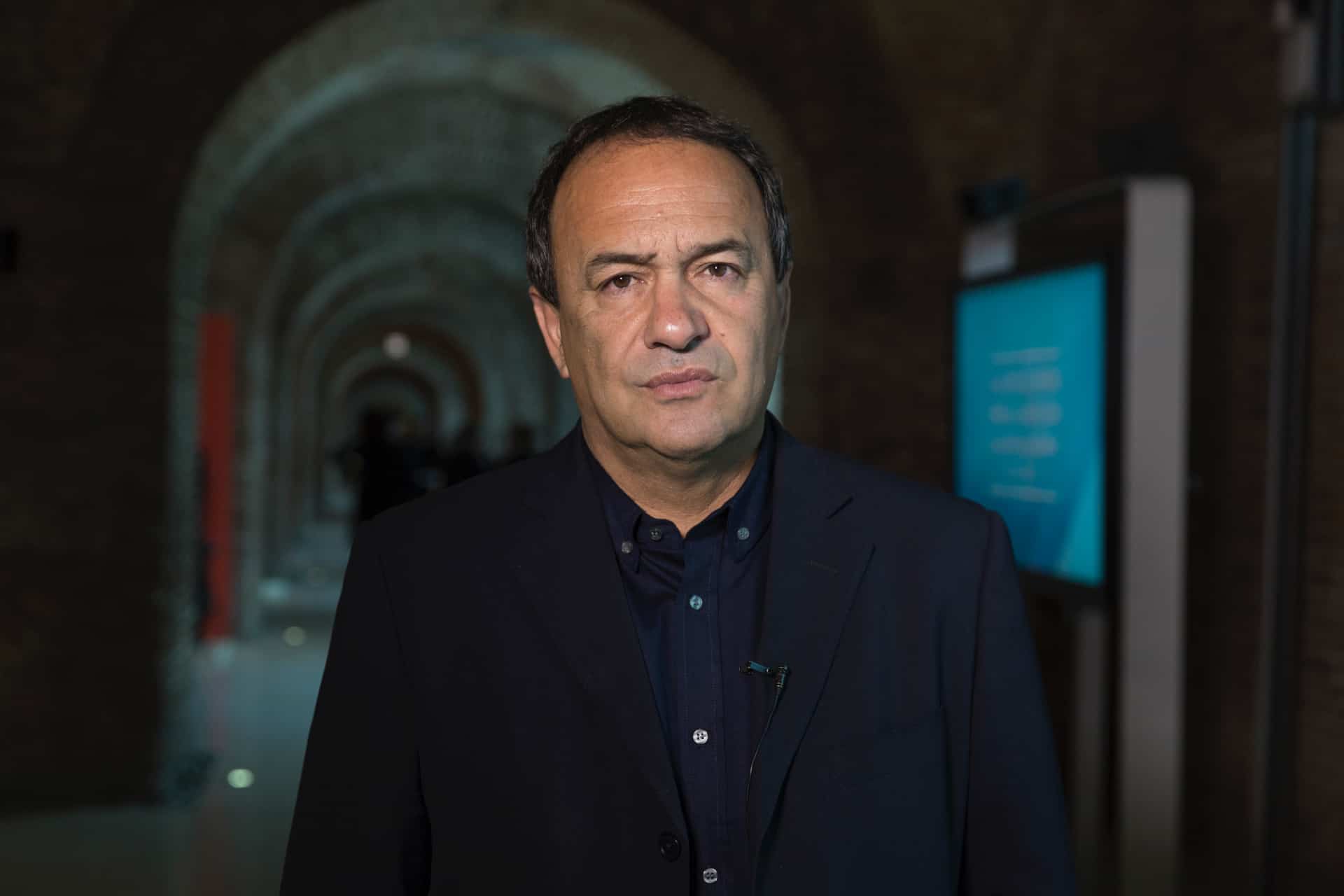

Domenico Lucano was declared as UN-aligned Person of the Year. Photo: Carlo Troiano

No country wants to be overrun by a tsunami of immigrants, but with sound management that never has to be the case; and sadly, the authorities know it. The story of Domenico Lucano, the pro-refugee mayor of Riace, who revitalised the languishing Italian town and made it a showcase of prosperity and integration and was hailed in 2016 by Fortune magazine as one of the world’s 50 greatest leaders, is all the proof one needs.

On the 30th September 2021, Lucano was sentenced to 13 years in prison for abetting illegal migration. His “crimes” included awarding waste collection contracts to companies that were set up to help migrants look for work and arranging a marriage of convenience to help a Nigerian woman escape prostitution and find legal work. After his conviction, Lucano told reporters:

“I spent my life chasing ideals, I fought against the mafia; I sided with the last ones, the refugees. And I don’t even have the money to pay the lawyers … today it all ends for me. There is no justice.”

These are the very people who could save the world and we are putting them behind bars. There are so many small towns around the world that are becoming abandoned. There are empty homes that can be filled, schools that can spring back to life, markets that can become a vibrant splash of colours again, but we prefer desolation to planning; pettiness to generosity; half bridges, to humanity.

5. What’s in it for me?

There have been a number of studies about the economic impact of immigration. Germany has proved particularly useful as a case study owing to Angela Merkel’s relatively open policy towards refugee immigration at the beginning of her mandate. Initial studies seemed optimistic about the effects, though later ones began to be a lot less so.

A recent study by Gerrit Manthei from the University of Freiburg, is once again evaluating the phenomenon in a positive light:

“By applying the model [Cobb–Douglas production function] to current immigration data from Germany, this study finds that refugee immigration can lead to long-term per capita growth in the host country and that the growth is higher if refugee immigrants are relatively young and have sufficiently high qualifications.”

What these studies do not show however, is what the impact could be if things were done differently; say, a la Lucano. Doing things differently means an ongoing evaluation of our laws in order to ensure that they are fit for purpose.

This may seem like a tall order, but at the end of the day, laws are an imposition on our freedoms and if they are to stand, they must do so on their continuing merit, however laborious assessing this may be. This will have the added benefit of making our legal system leaner, a reform which is long overdue.

All this said and done, however, there is an even more important issue at stake here; namely one of decency. Even if the influx of immigrants proves challenging and financially unrewarding, we have a moral obligation to do what we can to help these people in need. We are not talking about whether it is more or less profitable to import potatoes or turnips. We are dealing with human beings in dire straits whose lives and well being depend on our position to be able to help. The means are there, the willingness is generally not.

Indeed, welcoming those in need will therefore involve a drastic change of attitude from those of us living in our ivory towers. As voters we will keep putting pressure on politicians to adopt ever more stringent policies to keep these undesirables out. We will keep on plundering the planet, slaughtering animals and turning our backs on those in need without a thought about our human dignity and our responsibilities. We will keep on until forced to change by pandemics, climate catastrophes and bloodshed…

Or we can wake up and start taking control.