Finland is a young country, but one with a heartbreaking history. In this photo timeline, which consists of 11 events showcasing 80 photos, we’ll guide you through the country’s tragic history with Russia.

The February Manifesto and the Russification of Finland (1899)

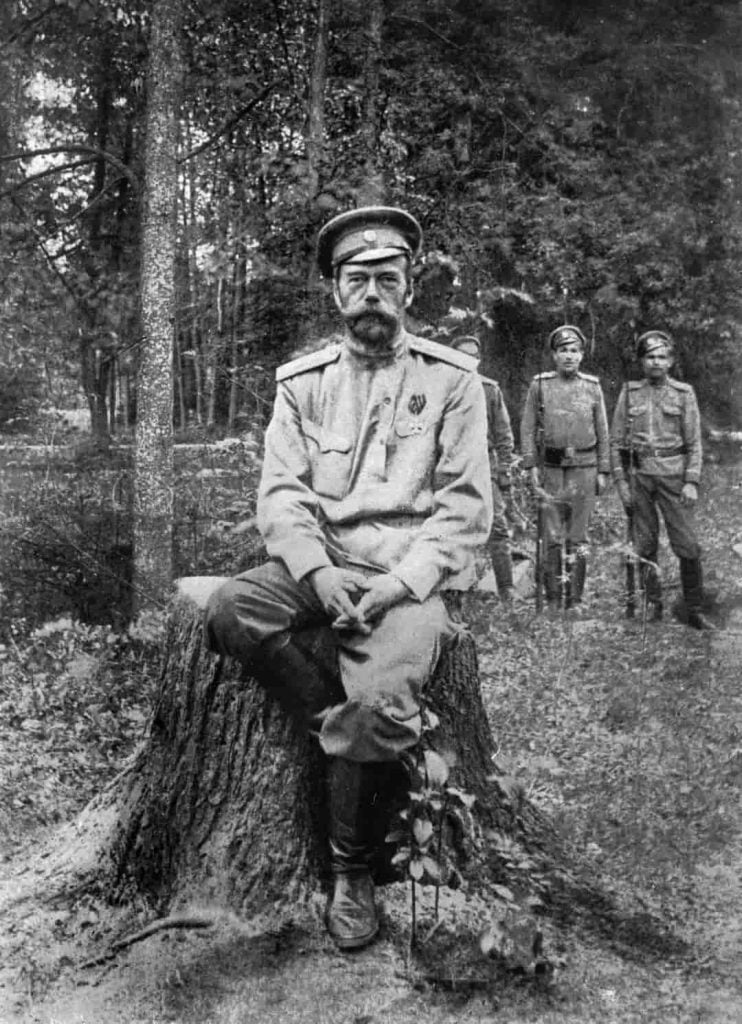

The February manifesto was part of the larger operation of the Russification of Finland during which Finnish territories were forced to align their cultures with that of the Russian empire. On the 5th of February 1899, Nicholas II of Russia, the Tsar of Russia, defined a new legislation order that asserted the imperial Russian government to rule over Finland without the consultation of the Finnish Senate.

Some of the articles of the legislation included: criminalising the act of subjecting followers of the Russian Orthodox church to the Lutheran church, placing even tighter Russian censorship on the Finnish press and subjecting the Finnish army to Russian rules of military service, essentially forcing Finns to serve in Russian units. The February Manifesto was soon followed by the Language Manifesto of 1900, which aimed to make Russian the main administrative language in government offices favouring the Russian minority that made up less than 3% of the Finnish society.

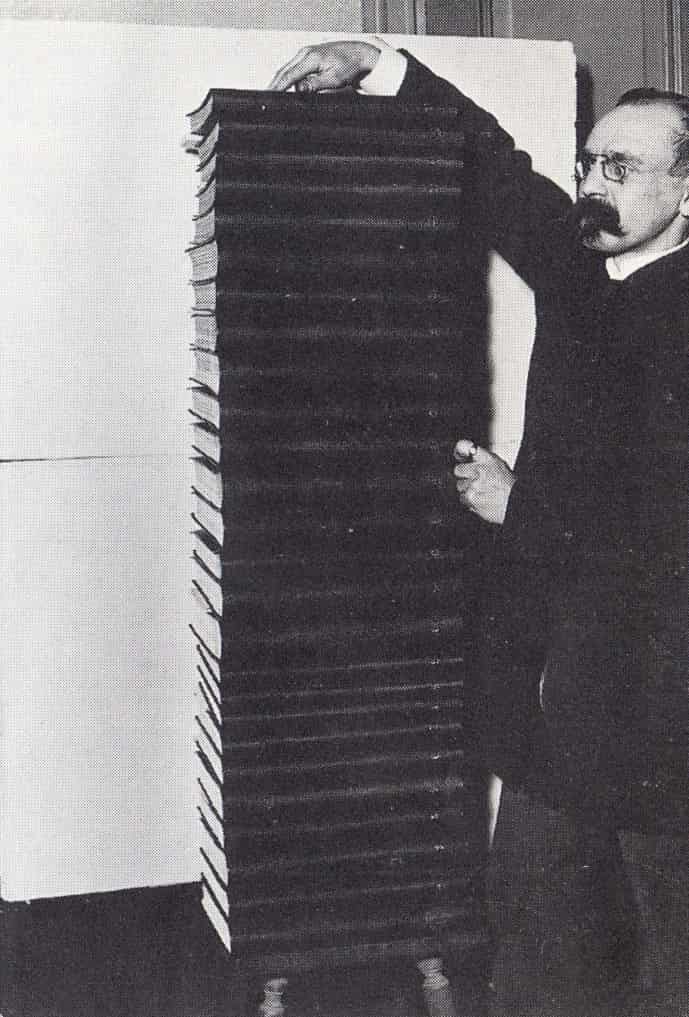

The Great Petition: Half a million protest petitions collected

The Tsar’s blatant attack on the Finnish autonomy was not left without a response. The move triggered an overwhelming response amongst many Finns that resulted in widespread civil disobedience and the collection of half a million protest petitions requesting Nicholas II to revoke the manifesto.

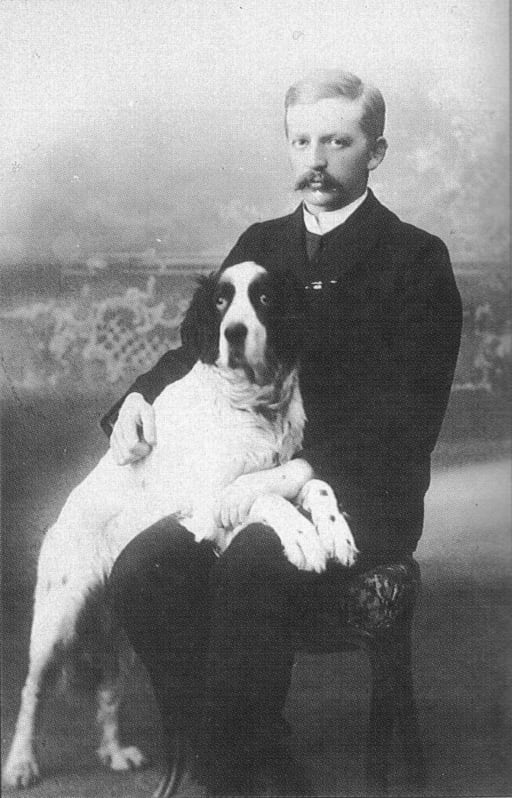

The assassination of Nikolay Bobrikov (1905)

Traitor!

Nikolay Bobrikov was an avid supporter of the Russian Russification project, which made him popular with the Tsar. In 1898, he was appointed as the Governor-General of Finland, the highest administrator and the military title of the Grand Duchy of Finland. Bobrikov, who had been influenced by the Russian conservative nationalist press, wanted to integrate Finland deeper into the rest of the empire so it was only natural that in 1903, because of his support and admiration of the Tsar he was given dictatorial powers by the Tsar to facilitate his Russification mission.

Despite his popularity with the emperor, Bobrikov was deeply disliked by the Finnish society. This inevitably led to his assassination by Eugen Schauman, a Finnish nationalist born in Kharkiv, in 1905.

The October Manifesto and the birth of the Finnish Parliament (1905)

The first Russian revolution began in 1905 and quickly spread through neighbouring Finland. Much like in Russia the revolutionary exasperation and ambitions were defused by the Tsar with the promise of sweeping reforms through his October Manifesto, which promised to guarantee civil liberties such as freedom of speech, the establishment of a broad franchise, and the creation of a legislative body in Russia (the Duma).

Women in parliament? Yes!

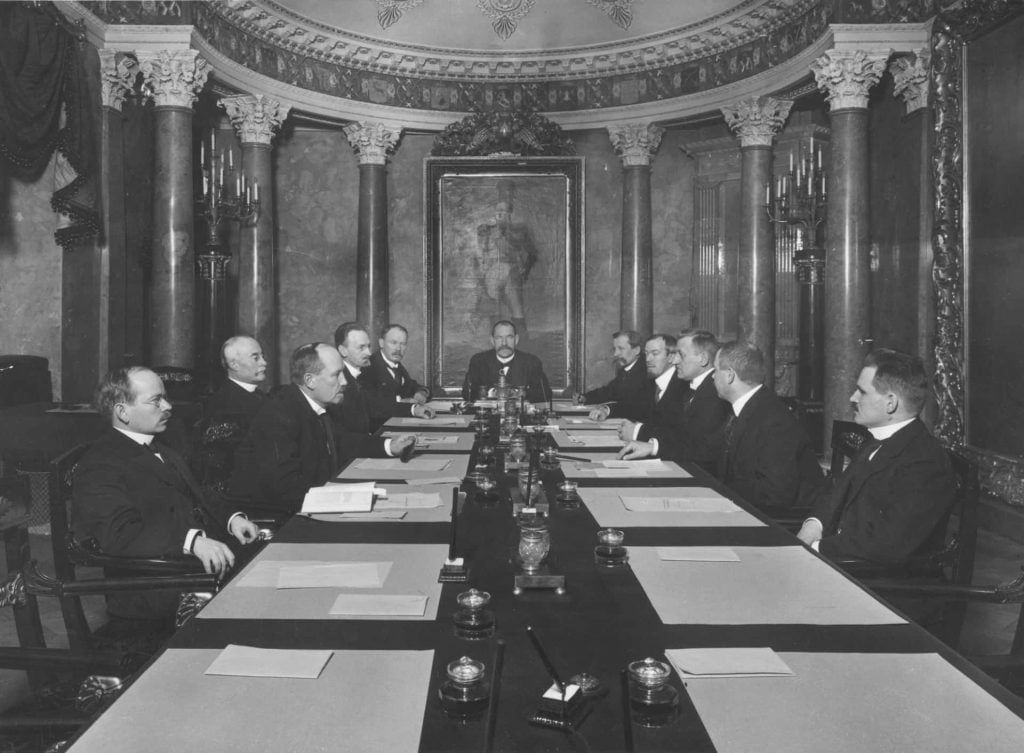

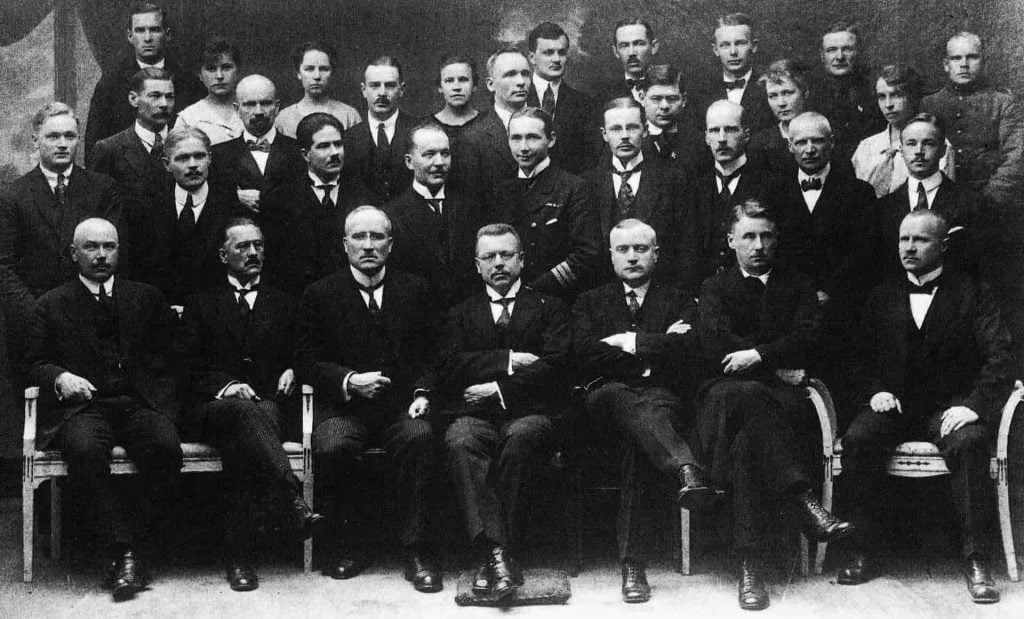

In 1906, Nicholas II proposed to replace the Finnish Diet with a modern, unicameral body. Universal suffrage and eligibility were implemented, making Finland the second country in the world to adopt universal suffrage. This gave the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of their wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, political stance, or any other restriction, subject only to relatively minor exceptions. Tsar’s proposals were largely accepted by the Finnish opposition as it resulted in the emergence of one million newly eligible voters.

The Parliament act of 1906 made Finland the second country, after New Zealand, to allow female citizens to cast their vote at the ballot box. After the first elections for the new parliament in 1907, the first Parliament had 19 female representatives.

Despite the momentous achievement, however, the Finnish Parliament remained neutralised by Nicholas II, a status that would continue until 1917 when Finland declared its independence.

Finnish independence from Russia (1917)

World War I brought Russia to revolution.

In 1917, Nicholas II abdicated on behalf of his son and drew up a new manifesto naming his brother, Grand Duke Michael, as the next Emperor of Russia. The abduction was widely criticised by the Russian Provisional Government as many believed that the future of government was for the people to will and decide, not the Tsar. Adding fuel to the fire, the Grand Duke brought 300 years of Tsarist autocracy to an end by declining to accept the throne, stating that he would take the throne only if that was the consensus of democratic action.

The end of the Romanov dynasty ignited hope in an independent Finland as many in Helsinki believed that the union between Russia and Finland had officially lost its legal legitimacy. Negotiations began between the Russian Provisional Government and Finnish authorities.

The Russian Provisional Government presented itself as an obdurate negotiator. Although the first drafts of the so-called Power Act, whereby the Finnish Parliament declared itself to hold all powers of legislation, aside from those matters relating to foreign policy and military issues, were relatively mild, the Provisional Government not only refused it but went on to dissolve the Finnish parliament completely.

However, it wasn’t long until the political sphere in Russia had shifted: The Bolsheviks, who were a Marxist faction led by Lenin, declared the right of self-determination, which included the right of complete secession.

On the 6th December 1917, the Finnish parliament adopted the Declaration with 100 votes against 88. Finally, Lenin’s Bolshevik government recognised the country on December 31.

The Finnish Civil War (1918)

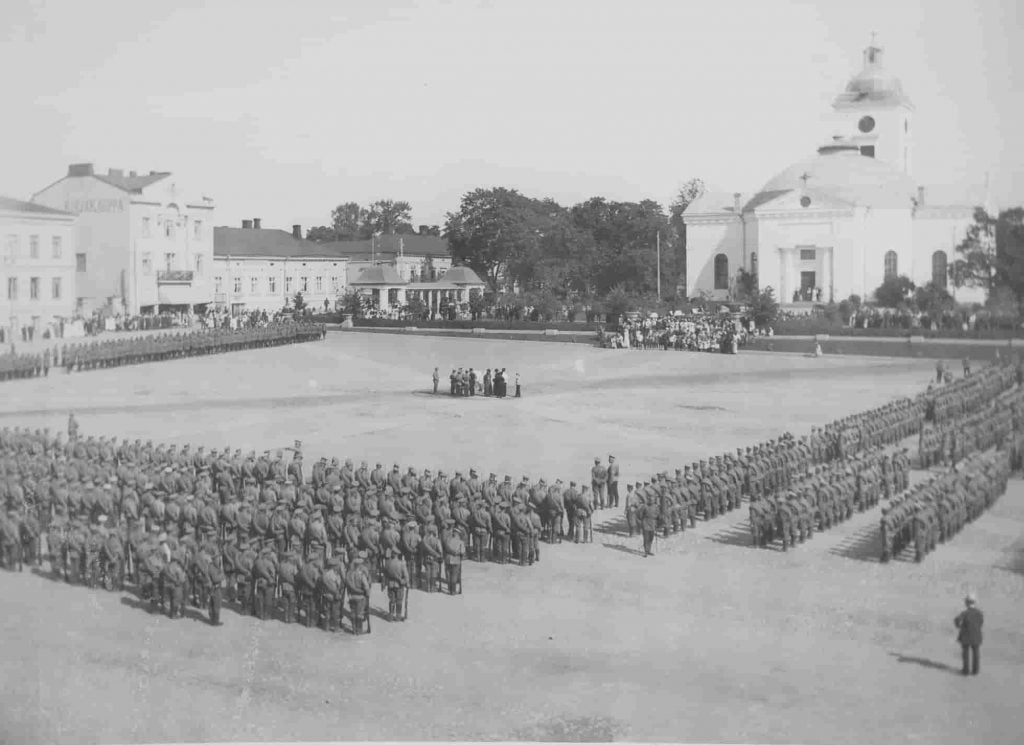

The beginning of 1918 marked the start of a new era for Finland. The collapse of the 300-year-old Romanov dynasty resulted in a power vacuum in Finland that led to a bitter civil war fought between the Reds, or labour movement, and the Whites or government troops.

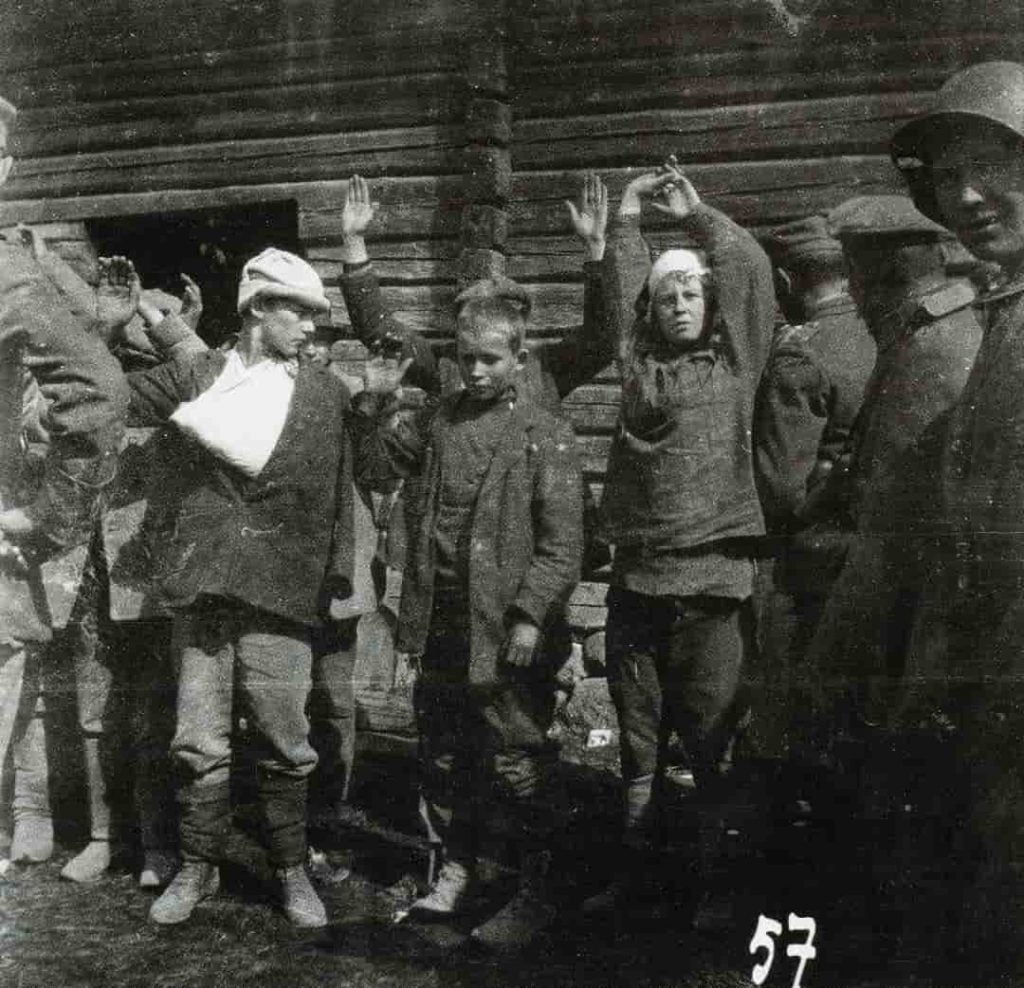

The Whites, who would emerge as the winners in this bloody conflict, were made up of the middle class and conservative state men and supported by the German Imperial Army. The Reds, on the other hand, were socialists, who were inspired and supported by an estimated 10,000 Red Russian soldiers, to replicate the success of Russia’s recent Bolshevik revolution.

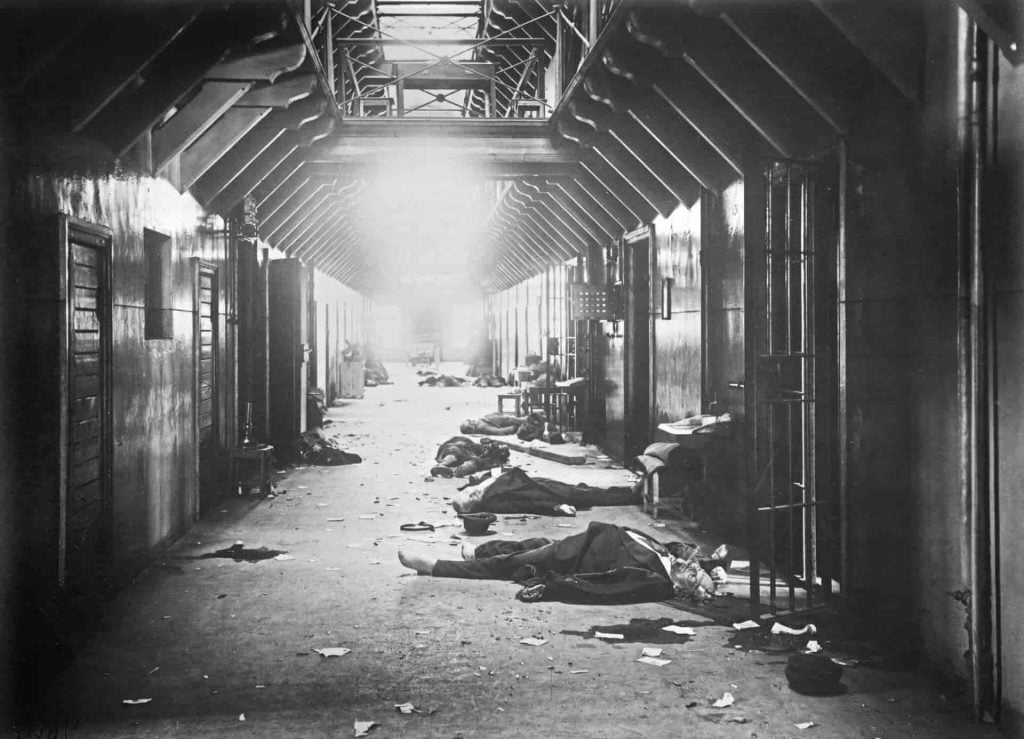

Blood everywhere…

The clash between the two factions of the society became inevitable after Svinhufvud, who was in charge of the Finnish senate after the country’s independence, made clear that it would make no concessions to the socialists and subsequently authorised its own White Guard to act as a state’s official security force to establish law and order.

The Finnish civil war was mainly fought in four key cities. These were the battles of Tampere and Vyborg, which were won by the Whites, and the Battles of Helsinki and Lahti, won by the Red guards and the German troops respectively.

It is believed that by the end of the war almost every working-class family had a direct experience of suffering or death at the hands of the Whites. It is estimated that around 12,500 Red prisoners died of malnutrition and disease in camps. In total, about 40,000 people died in the conflict.

The conflict eventually resulted in a German hegemony.

East Karelian uprising and the treaty of Tartu (1921)

Today the region of Karelian is divided between northwestern Russia and Finland. However, owing to its complicated history, the region of Karelian has an important historical significance for Russia, Finland, and Sweden, therefore, socially labelling the territory, as either one of these three nations would like to do, would be like fitting a square peg in a round hole.

The border question relating to East Karelian remained unsettled between Russia and Finland after the war. During the 1920s, the region was in official control of the Bolsheviks. Moreover, Many in Eastern Karelian were also tired of the Bolshevik regime’s false promises of respect for their autonomy.

In 1920, after the British troops, who occupied Karelian as a part of the Viena Expedition, departed, Karelian ethnic nationalists arranged a meeting in Ukhta and decided that White Karelia should become an independent nation. The Red Army, however, suppressed this uprising and in the Summer of 1920, the Temporary Government of Ukhta fled to Finland.

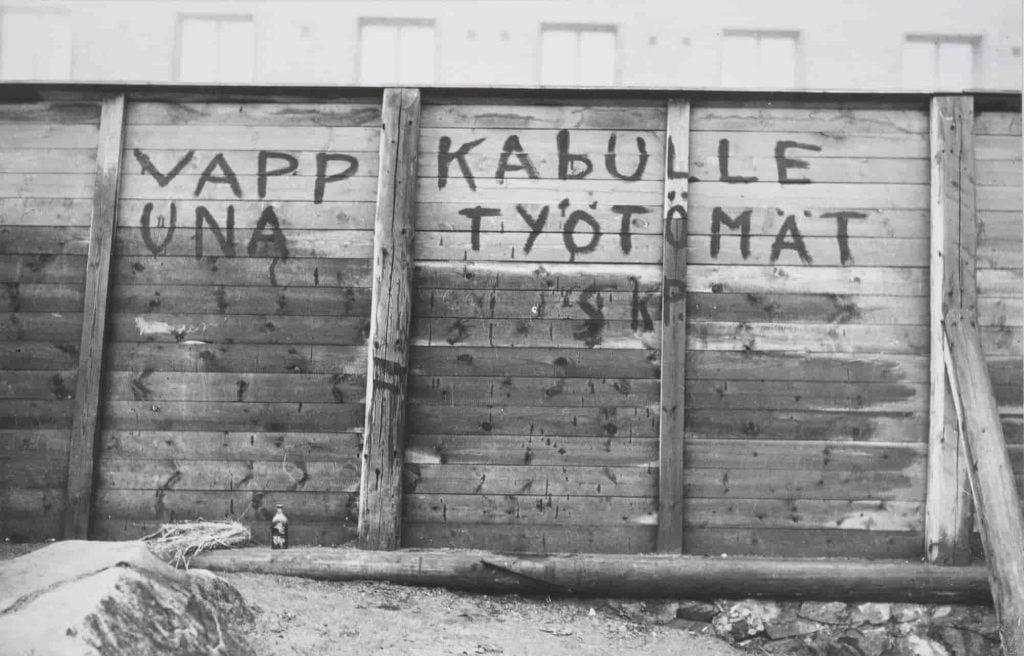

We must help our Baltic friends

The uprising eventually escalated into a military conflict in late 1921. Having finally gained their national independence, many Finns felt that they had an obligation to help other Baltic Finns to attain the same. Although the official Finnish support of the uprising was passive, the conflict caused a notable regression in Finnish-Russian diplomatic relations.

The conflict ended in March 1922 with the signing of the Treaty of Tartu in Tartu, Estonia whereby Finland agreed to leave the joined and then “occupied” areas of Repola and Porajärvi in East Karelia.

The treaty was eventually violated by the Soviet Union in 1939 when it invaded Finland during the Winter War.

Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact (1932)

The Bolshevik’s involvement in the Finnish revolution, Tsarist policies of Russification and ongoing Soviet efforts to foment unrest in Finland, all contributed to the growing mistrust between the two nations. Moreover, during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the Soviet Union could not handle additional threats from neighbouring countries.

To address this mutual distrust the Soviet Union and Finland signed a ten-year non-aggression pact in 1932. The pact obligated both parties to respect each other’s borders and exercise neutrality during conflicts. Moreover, in the case any disputes arose, both parties of the pact promised to solve them peacefully and neutrally.

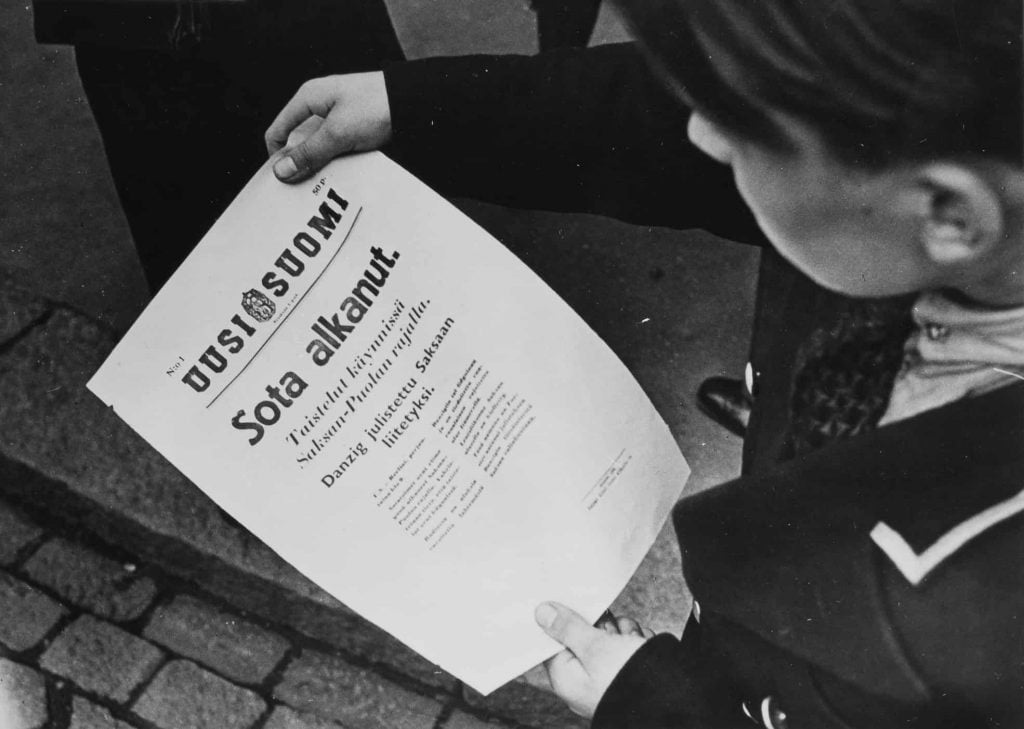

Soviet Union invades Finland during the Winter War (1939)

Russia has always had quite a reputation when it came to planning “false flag” attacks for invasions. In 1939, on the outskirts of the Second World War arena, the Russian village of Mainila, which was close to the Finnish border, was targeted by shelling. The attack fabricated by the State Security of the Soviet Union (NKVD) quickly escalated.

As per the rules of the Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact, Finland proposed a neutral investigation into the incident, but the Soviet Union refused and broke diplomatic relations, which would later develop into the Winter War.

The underlying cause of the Winter War was obvious: the Soviet Union was concerned about Nazi Germany’s expansionism. The Soviets demanded negotiations with Finland, however, the Finnish government’s guarantees that the country would not side with the Germans were not accepted by the Soviets, who wanted Finland to cede small parcels of territory. In particular, parts of the northern shore of the Gulf of Finland, from which they could prevent hostile forces from entering Leningrad.

Finland was neither tempted nor fooled by the Soviet Union’s proposals. The understanding in Helsinki was that accepting such unreasonable demands would jeopardise the country’s neutral status and risk its territorial integrity.

The Winter War was a Soviet war of aggression — Boris Yeltsin, the first President of the Russian Federation

However, the Soviet determination to achieve its national security goals led the country to war with Finland, which it invaded in 1939, three months after the outbreak of World War II.

The war unfolded in one of the coldest winters in recorded history with temperatures as low as -43 degrees Celsius (-45 Fahrenheit). Despite possessing superior military power, the Soviet Union suffered terrible losses and initially made little progress. By the end of the war, on the Russian side, about 150,000 troops lost their lives while an additional 188,000 were reported wounded. On the Finnish side, the bloody war resulted in more than 25,000 dead and about 43,000 wounded, a significant number considering that at the time, the population of Finland amounted to only 3.5 million.

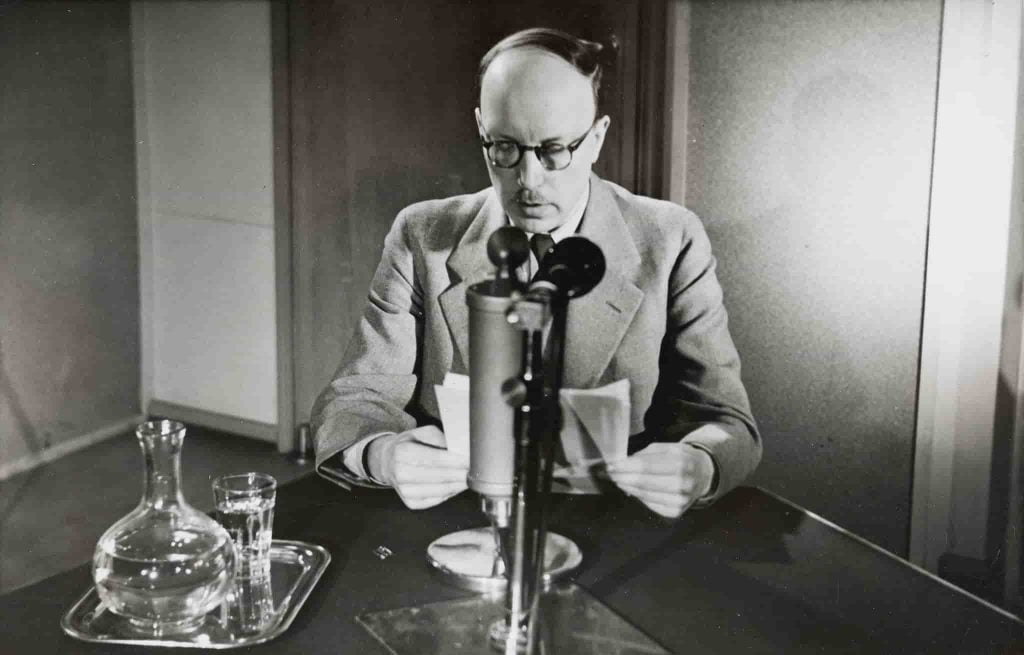

In 1939, Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany called Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The pact was made fun of by many Finns. So when during a public broadcast, the Soviet’s foreign minister of the time, Vyacheslav Molotov, declared that bombing missions over Finland were in fact airborne humanitarian food deliveries for their starving neighbours, many Finns saw an opportunity. The name Molotov Cocktails was coined for an improvised explosive bomb, which meant “A drink to go with the food.”

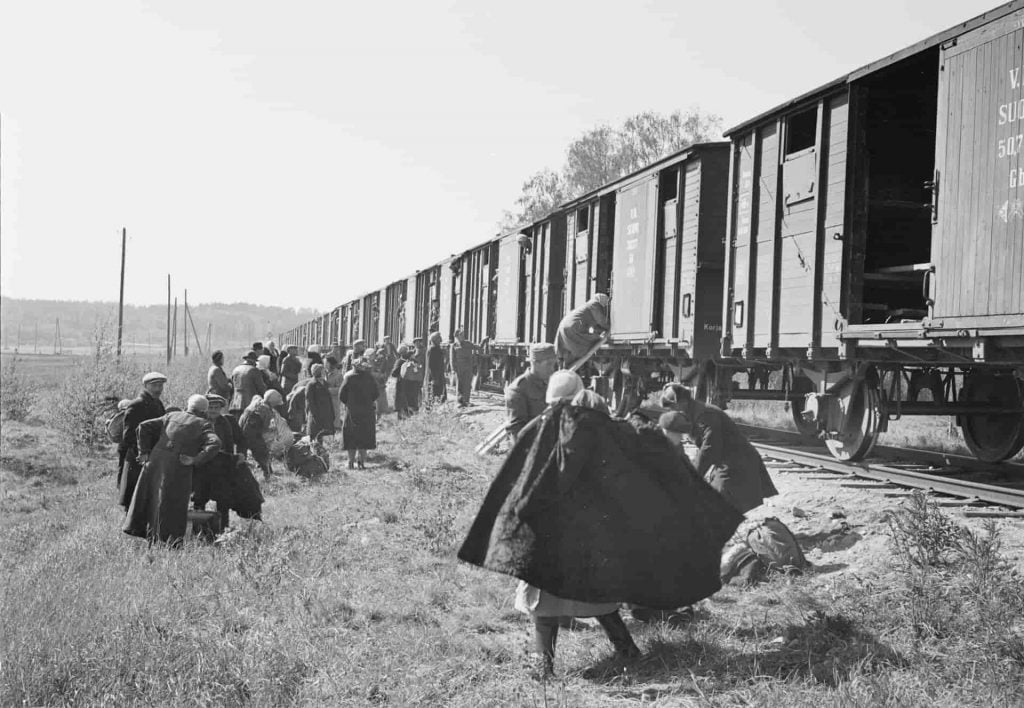

Despite the incredible resistance and great sense of humour, Finnish troops could not last long. By early March 1940, the Finnish army was on the verge of total collapse. The only option for the country was now to agree to the Soviet terms, which were encompassed in the Peace of Moscow. As per the terms of the peace deal, Finland ceded 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union. This included Finland’s second-largest city, Viipuri. One-eighth of Finland’s population lived in these ceded territories; this meant that nearly all of them lost their homes.

The Continuation war and Finnish support of Hitler (1941)

During the succeeding months after the Winter War, the Soviet Union’s meddling in Finnish politics and its unreasonable demands, most of which were not even called for by the Peace of Moscow treaty, grew. This convinced many Finns of a continuing desire from the Soviet Union to suppress and control them.

Moreover, after the fall of France, Hitler wanted to destroy what he saw as Stalin’s “Jewish Bolshevist” regime. He, therefore, saw Finland as a staging base for his forthcoming invasion of the Soviet Union. Finland, too, had enough of the Soviet’s demands and saw this as an opportunity to recover the ceded territories it had lost during the Winter War.

This was a marriage of convenience. German troops arrived in increasing numbers and by the beginning of 1941, the Finnish military was prepared to join the Germans in the invasion of Russia. Finland however, knew that if the country were to appear as the aggressor, it would have been political suicide. Therefore, it waited three days after the Soviet attack on its aerospace from which German planes took off. This gave Finland the pretext it sought for the attack.

In June 1941 Finland became co-belligerent of Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union under what was called Operation Barbarossa. Less than a few months later, Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia, two Winter War concessions to the Soviet Union, had been reclaimed by Finland. By August, Finnish troops had even reached the prewar boundaries.

The Russians are attacking? Join the Nazis! The Nazis are losing? Join the Allies!

There was mounting pressure from the Allies for Finland to end its association with the Nazis. In July 1941, the United Kingdom signed an agreement of joint action with the Soviet Union, which led the British government to present Finland with an ultimatum. Finland refused to comply and Brittain, together with the rest of the Commonwealth, declared war on Finland. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill later sent a private letter to Mannerheim, the then President of Finland, which expressed how “deeply grieved” he was that he had to declare war on his country.

Soon Finland found itself in a corner. After the failure of the Battle of Moscow, all German ambitions for a fast victory against the Soviet Union were crushed. Moreover, the Soviet counter-offensives in December 1941 largely ended the German threat. Under such circumstances, there was no other way to end hostilities between Finland and the USSR, but to sign a peace agreement.

The terms of the peace between Finland and the USSR required the Finns to expel German troops in Finland through Lapland into Norway (The Lapland War). This was a sad and dreary episode as Finnish soldiers were compelled to fight their former comrades-in-arms.

The casualties of World War II amounted to about 86,000, three times the losses the country suffered in the civil war. In addition, about 57,000 Finns were permanently disabled. The bloody war also left 24,000 widows, 50,000 orphans and one and half million refugees from Lapland and other parts of Finland. Adding insult to injury, as part of the peace negotiations with the Soviets, Finland was obliged to pay the reparations worth $300 million, which amounts to more than 6 billion US dollars in 2022.

Finland’s partnership with the Nazis remains a dark stain on the history of the country. Nevertheless, despite Finland’s support of Hitler’s ambitions, Finland refused to allow Nazi anti-Semitic policies to be exercised in Finland. Jews and Jewish refugees were not only welcomed in Finland but, in one of the most outré events of the war, fought alongside Hitler.

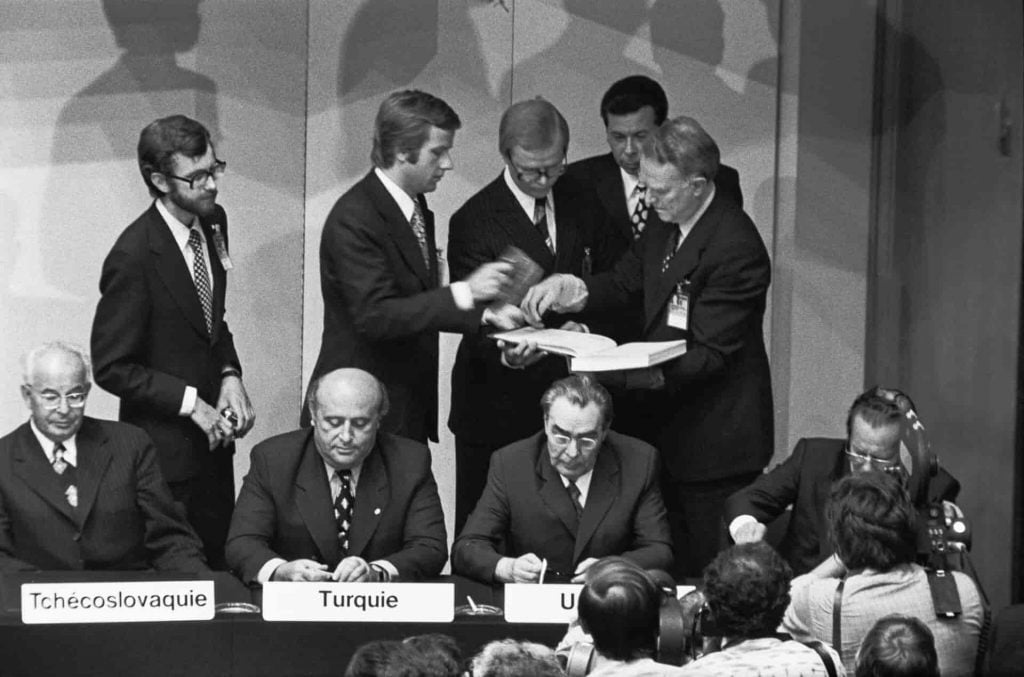

Finlandisation becomes synonymous with neutrality (1960-1990)

Finland’s relationship with the Soviet Union was permanently altered by the war. In 1948, Finnish and Soviet delegates signed the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance. The agreement, named “Paasikivi–Kekkonen” was part of a new foreign policy doctrine that was developed by president Juho Kusti Paasikivi and followed to the point by his successor Urho Kekkonen. .

The strategy, which had neutrality at the heart of it, ensured the survival of Finland as an independent sovereign, democratic country located in the proximity of the Soviet Union.

This meant that Finnish newspapers and politics had to change their attitudes to match the values of what the Soviets were thought to favour and approve. During this time, for example, reprinting and distribution of “anti-soviet” materials were prohibited.

This forced neutrality lasted until 1985 when Mikhail Gorbachev came to the Soviet leadership scene, which led to the USSR’s subsequent dissolution in 1991. Once the Soviet-Finnish Mutual Assistance Pact was replaced with treaties on general cooperation and trade, Finns found themselves on an equal footing with Russia. However, Russia continues to present an imminent threat to the country’s security.

Finland sends application to the biggest military alliance in history, NATO (2022)

The 2022 invasion of Ukraine which resembled those of Hitler during the Second World War, made it clear that if it comes down to it, Moscow and its insane ruler, could and likely would attack Helsinki.

This was a turning point for the Finnish government. Traditionally, due to the long-standing neutral policy towards Russia, a majority of Finns had long opposed membership in the union.

After Russia’s invasion, however, support for Nato membership soared to 76%. This led Finnish President Sauli Niinistö and prime minister, Sanna Marin, to declare that they would apply for NATO membership without delay. After the Finnish government’s proposal was approved in parliament by 188 votes to 8 in May 2022, the next day, the country submitted its official application to NATO in Brussels.