Powerful women: The story of Artemisia Gentileschi and her 1639 self-portrait

The Artemisia, also known as the mugwort flower, is a symbol of gratitude, the leaves of the plant give energy and certainly have nothing to do with addiction to absinthe, a substance obtained from them, which generates addiction when associated with alcoholic substances. Gratitude is the feeling that each of us should have towards every artist. Here, we can also grasp the energy and strength in art through historical information referable to a great woman and artist: Artemisia Gentileschi.

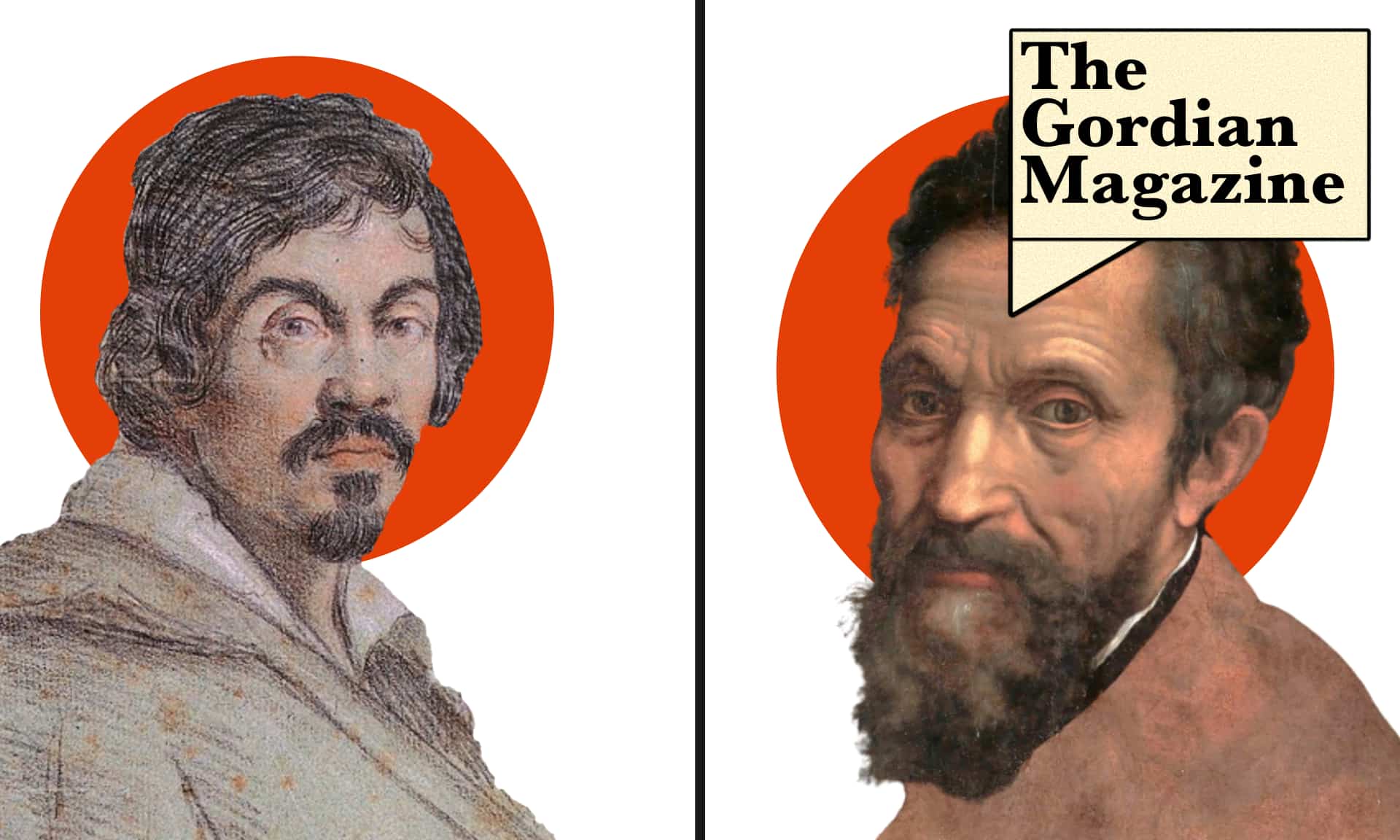

As I did with Carvavaggio, whose history I found it necessary to trace, I will do the same with Artemisia who was herself a painter of the Caravaggesque school.

I believe that the environment, and precisely the events in the history belonging to each of us, determines and conditions our individual way of feeling and living; often, if not in most cases, these traces remain silent, hidden from the eyes of most. In art, however, these same traces find form and a loud voice, telling us about intimate and personal aspects of those born with the gift of knowing how to speak about themselves through this medium.

Portrait of Orazio Gentileschi by Lucas Vorsterman

A painter of the Caravaggesque school, Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593 to Prudenzia Montoni and Orazio Gentileschi, and she died in Naples around 1656. The father figure, the only parental figure of reference after Prudenzia’s premature death, was fundamental in Artemisia’s artistic and personal training. The man, originally from Pisa, was a painter.

Orazio’s style at the beginning of his career was quite devoid of character and originality. Only once he moved to Rome was the artist able to find and above all to manifest his own way of expressing himself, strongly influenced and inspired by the unconventional painting of Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio.

Nowadays it is simple, if not obvious, to admire Caravaggio, but at the time Merisi’s bold choices were not always understood and working like him, or rather in his style, was not so conventional; in a Rome full of contradictions, divided between tradition and innovation, following the road inaugurated by Caravaggio meant having courage. Orazio embarked on this new pictorial path by modifying and enriching what was his initial style, involving the young Artemisia in this new artistic journey.

Early training

Orazio personally took care of the artistic education of his daughter, allowing her to cultivate her personal ambitions beyond the tight meshes that harnessed the lives of women of the time. The painter, recognizing Artemisia’s artistic qualities, brought her closer to figurative art, first teaching her how to master the “materials of the trade”, then by encouraging her how to familiarise with famous works by asking her work from drawings. Finally, he allowed his daughter to intervene directly in his own canvases.

We do not have extensive documentary sources on Artemisia’s artistic training; to tell the truth we have almost nothing that documents these first years of study and exercises of technique. However, a proud letter from Orazio, written in 1612 to the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, makes us understand that at that time his daughter already had adequate skills to express herself in art with maturity and mastery.

Raped and abused by her teacher, Agostino Tassi

Agostino Tassi

Another certain fact about Artemisia’s formation is linked to what is certainly the most traumatic and well-known event in the young artist’s life. As already mentioned, Orazio was well aware of the artistic value of his daughter, for this reason he decided to send her to perfect the pictorial techniques at the studio of one of his friends, the painter: Agostino Tassi. This man, despite having artistic abilities, was known above all for his angry character, which, however, had never directly revealed itself towards Orazio Gentileschi, who was sure of the man’s loyalty and feelings of friendship. He therefore did not hesitate to entrust the young Artemisia to him in order to improve her technique.

Unfortunately, the true nature of Augustino manifested itself precisely towards the young woman who, after refusing the painter’s advances, in 1611 was the victim of violence by the artist who was supposed to be her teacher. Artemisia was actually a victim of Augustino in more ways than one, because after having raped her, he promised a reparatory marriage in order to continue to frequent her.

Only in 1612 Artemisia and her father Orazio discovered that Agostino was already married and that therefore marriage was out of the question. Doubly wounded in his honor, Orazio, together with his daughter, denounced Tassi’s violence to Pope Paul V.

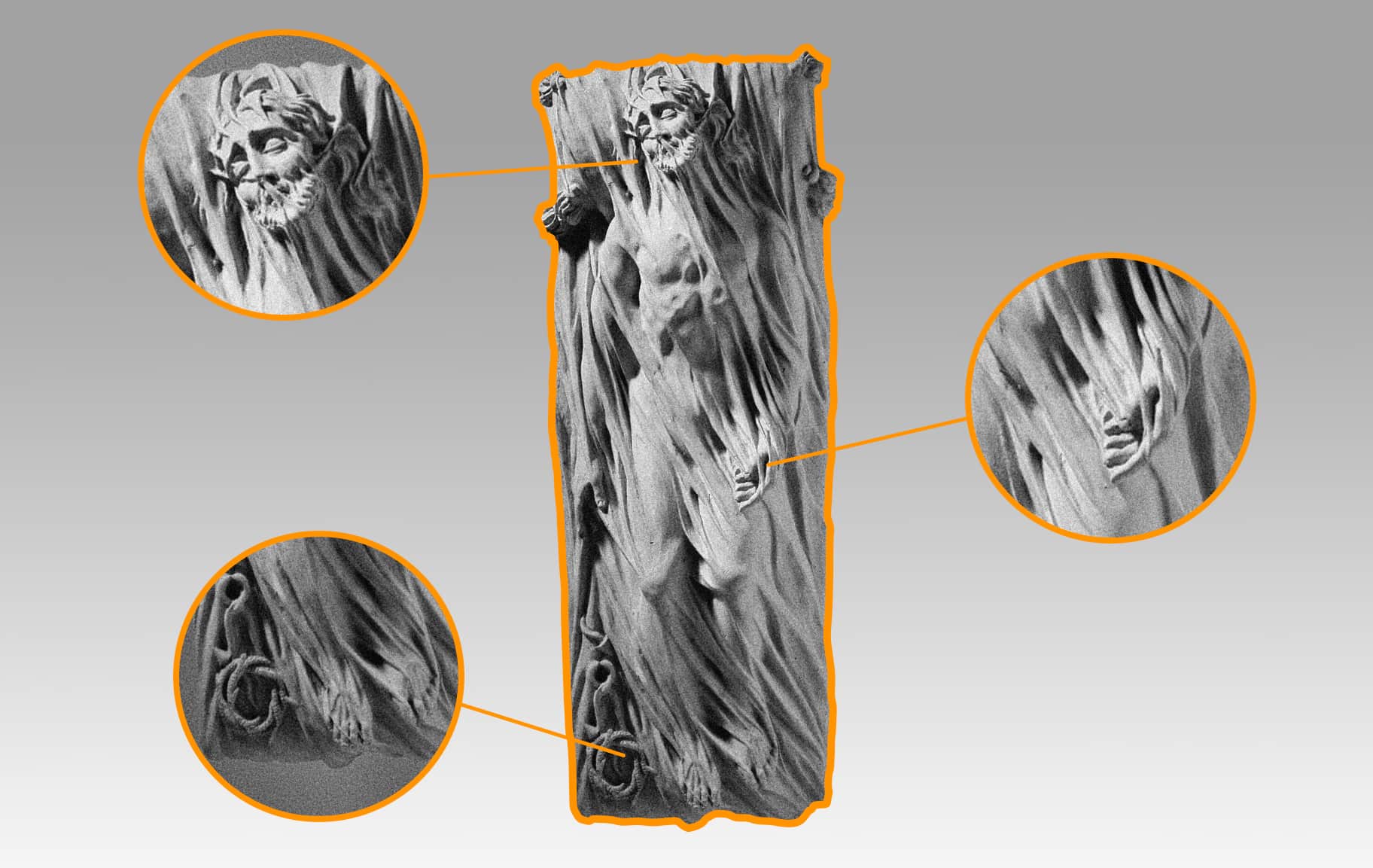

The young woman courageously submitted herself in court to all the humiliating evidence requirements that were demanded at that time for victims of such violence. Artemisia, strong in the support of her father, but above all driven by great will and determination, managed to overcome all the humiliating bureaucratic processes that tended to judge women more harshly than the real perpetrators of the crime. She thus demonstrated also in her private life the same strength that can be seen in the women protagonists of her paintings. During the trial, the young Artemisia also had to prove the validity of her accusation by being subjected to physical torture, especially to the hands.

These ‘procedures’ could have ended her career, but the painter was able to resist the pain with courage, until Tassi was sentenced in November 1612.

In reality, the painter did not actually serve his sentence, but paradoxically continued the “popular trial” against Artemisia, who the day after the conviction of her rapist was in fact forced to marry a man, chosen for her by her father, to try to save her reputation as a woman and a painter.

Moving to Florence marked a new chapter in Artemisia’s life…

After this last act against her, Artemisia Gentileschi chose to leave Rome and her father, and together with her husband moved to Florence. When she arrived in Tuscany, she finally saw the recognition she deserved, becoming part of the Medici circle of artists chosen by Cosimo II to give prestige to the culture of the city. Florence was also important for expanding Artemisia’s personal connections and she became friends with Galileo Galilei and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Thanks to the latter, she also managed to get in touch and then to be admitted to the Academy of Drawing Arts in Florence.

While Artemisia’s fame increased, her family’s assets decreased due to her husband’s debts and the economic situation became so serious that it pushed the family to return to Rome. The welcome she received made it clear to everyone that Artemisia’s artistic value was finally recognized in Rome, but the painter did not stay long in the city; she made numerous trips that took her to Venice, Genoa, England and above all to Naples where finally began to feel at home. It was in Naples that Artemisia died, most likely during the terrible plague that struck the city in 1656.

Not only a painter, but a champion of women’s rights

Past and even contemporary evaluations have focused excessively on the personal stories of the painter, partly leaving out the artistic value of the woman.

I believe it is essential to continue talking about Artemisia Gentileschi while highlighting her value as a painter. Focusing excessively on the personal stories of the painter does not do her justice. Artemisia was not only a champion of her own rights or women’s rights, she was, for most of her life, an artist who found herself fighting with great determination to be recognised and valued as a painter on the same standing as her male colleagues.

I want to say that if it is true that Artemisia fought to have her rights as a woman recognized, it is equally true that she fought with equal determination to continue living on art and as an artist, to the point of not hesitating to leave Rome, her city of origin and training.

Just to underline and emphasize the role of Artemisia as a painter, I decided not to talk about her through the numerous heroine protagonists of her paintings, but through the examination of a self-portrait completed in 1639 and currently preserved in London at Kensington Palace.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, analysis

A self-portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi completed in 1639 and currently preserved in London at Kensington Palace.

In this painting created for Charles I, the woman is portrayed as the essence of painting in an allegory that celebrates this art. The image presents an idealised Artemisia, where she has deliberately transformed her own appearance and colours.

In fact, the woman depicted on the canvas has black hair, not auburn like Artemisia had, gathered at the bottom in a rather disordered way. Her fair-skinned face is not turned towards the audience, but rather towards a canvas she is working on, and therefore her features are not visible to the observer. The only “charming” element in the painting is represented by a long gold chain hanging from the woman’s neck, from which a mask-shaped medallion hangs. Her right arm is raised, holding a brush in the act of painting, while with her left hand she holds other brushes and the palette.

The three-quarter pose of the woman’s figure suggests that Artemisia had to use two mirrors in order to create this self-portrait. In her visible features, we can clearly detect the physical resemblance and attitudes of the female characters that populate her paintings. What also appears evident to me here, even more than the similarity of features, is the setting of the hands, common to all the women designed by Artemisia; heroines who manage to escape their executioners and obtain justice These heroines are driven by a force that is not only interior, but also physical and one that acts precisely through skilled, strong and industrious hands.

Despite the obvious points of contact with other figures she painted, in this allegory Artemisia also represents herself in her “nakedness”, revealing her true essence to the world, ceasing to be Artemisia the woman, in order expose the very essence of painting as well as the profound and tumultuous creative process that was within her.