How Caravaggio's 'The Burial of Saint Lucy' Transforms the Divine into the Earthly

Caravaggio's portrayal, St. Lucy forsakes heavenly glory for a gritty burial scene, which reflects the artist's personal struggles and innovative use of light.

Breaking from iconic traditions

Both artistic and sculptural representations traditionally depict St. Lucy in celestial grandeur. She is often shown holding the palm of her martyrdom, which occurred in Syracuse in 304, in one hand, and a saucer containing her eyes in the other.

This iconographic element is a nod to her role as the protector of sight, although it bears no relation to the martyrdom she endured. The origin of this specific veneration is tied to her name: Lucy, or Lucia, derives from the Latin term ’lux,’ meaning light—an element naturally associated with eyesight.

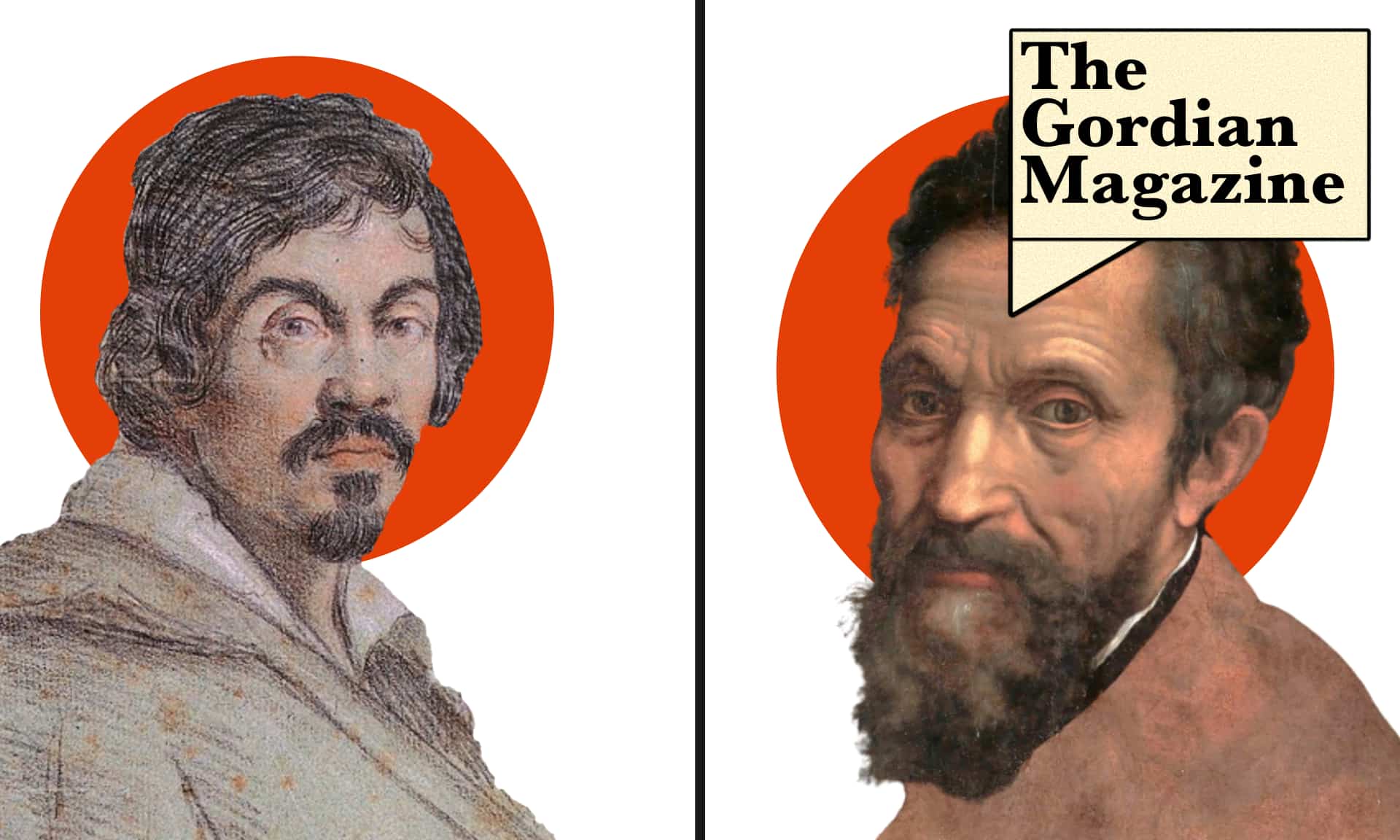

Breaking away from this established tradition is the Burial of Saint Lucy by Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio. Painted for a church dedicated to the saint from Syracuse, this masterpiece marks a stark departure as it presents St. Lucy not in heavenly glory but in the solemn moment of her burial.

Santa Lucia Alla Badia Church, the home of Caravaggio’s ‘The Burial of Saint Lucy. Photo: Zde/Wikimedia

Personal struggles shape art

Considering that Caravaggio’s presence in Syracuse is documented shortly after his departure from Malta, where he had taken refuge following his death sentence in Rome, the work was almost certainly created in 1609.

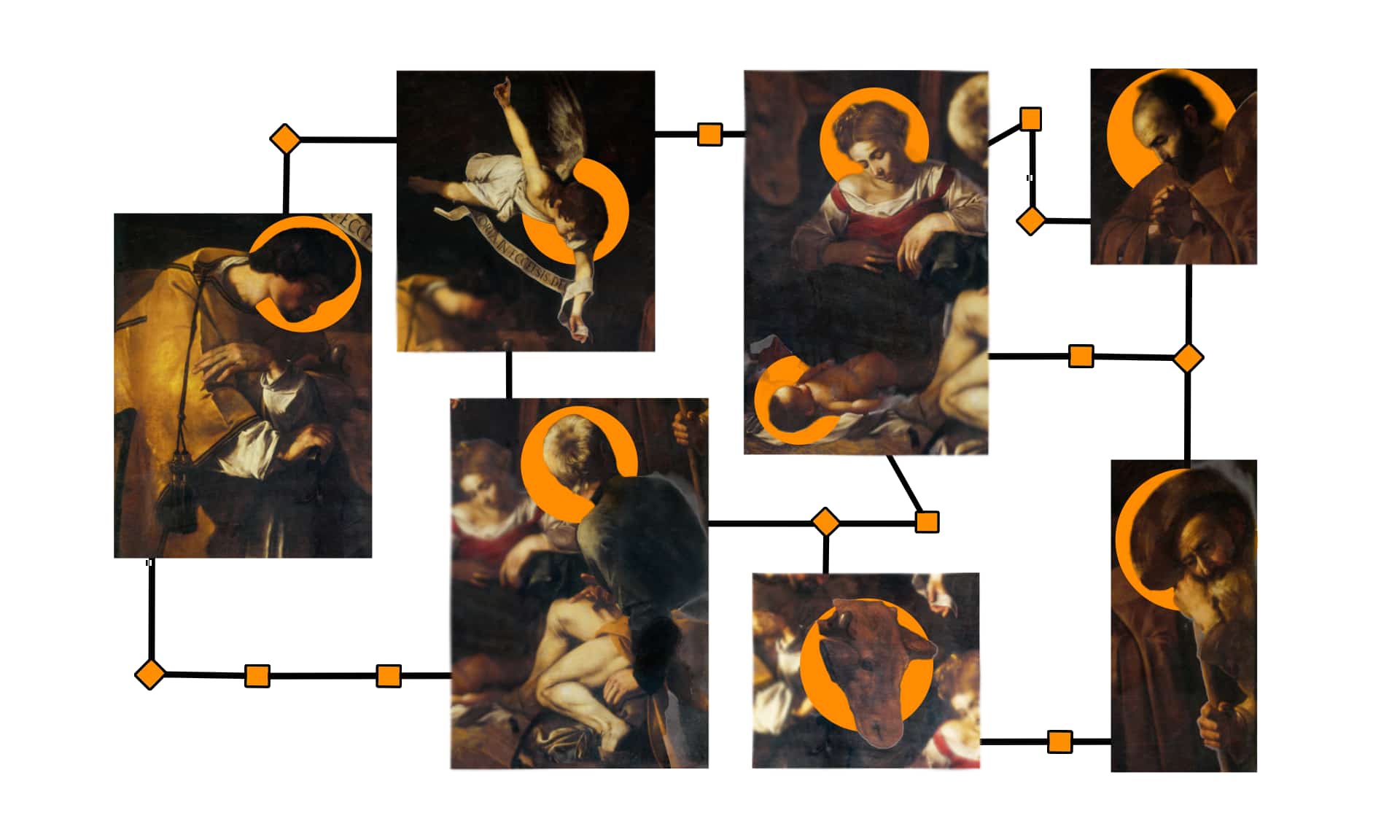

This period coincides with a particular moment in the artist’s life, in which the dramatic evolution of his complex personality is widely witnessed in his final works, in which he actually overturns his own vision and conception of artistic construction.

In this canvas, every single scenic or technical element testifies to and amplifies the strong inner turmoil of the artist. The artist is fully aware of his death sentence, and makes death, in particular the beheading to which he was sentenced, an element that is not only conceptually unavoidable but also indispensable in his artistic production.

Evolution of light and shadow

The space in which the burial scene is set has nothing in common with the “full” and dense spaces of his Roman works.

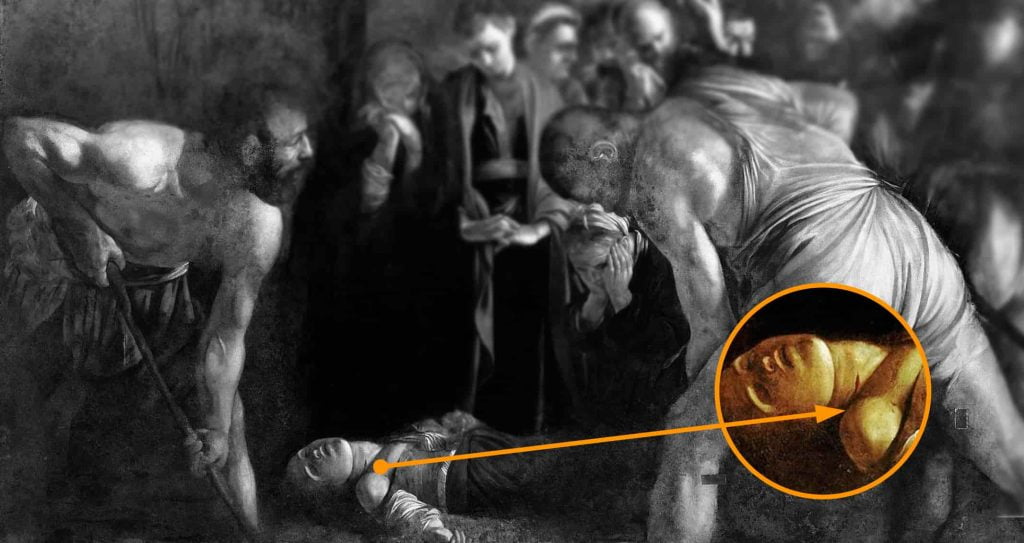

The environment is deliberately empty, both to fully convey the idea of the arcosolium of the catacombs present at the site of Lucy’s martyrdom and to focus the observer’s attention on the protagonists of the painting, all positioned in the lower part of the canvas.

As in the case of ‘Conversion of Paul’, where immediate attention is directed more at the horse than the saint; here too, the gaze falls more on the two men positioned next to her body, busy digging the grave that will receive the young woman’s corpse.

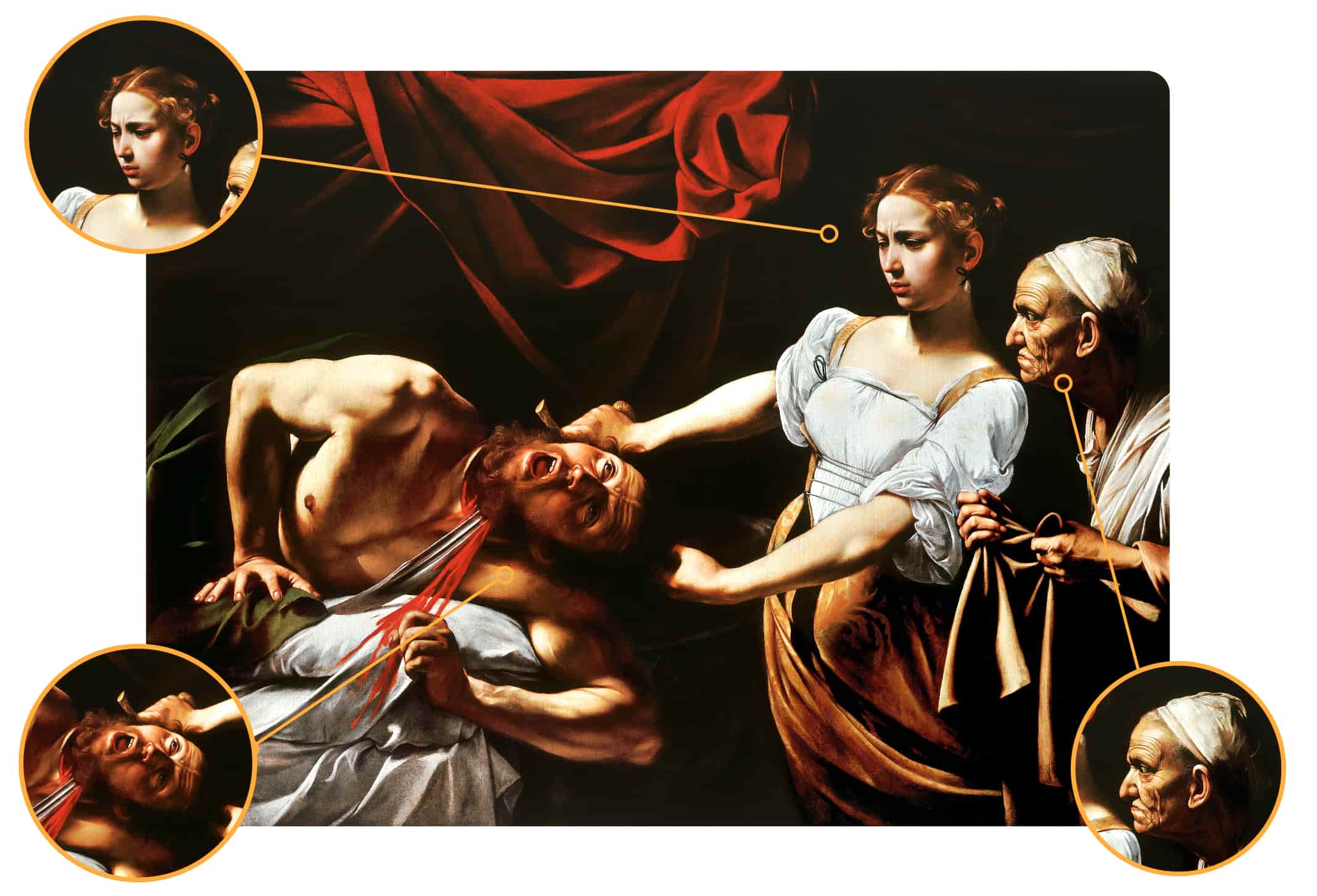

Two men dig a grave, seemingly detached, as Lucy appears with a near-severed head from a stab in the throat.

Lucy, killed by a stab in the throat (jugulatio), appears with her head almost severed by the force of the blow, ending up, albeit less conspicuously, among the many severed heads obsessively depicted by Caravaggio in the last years of his life.

The two men mechanically perform their movements without the slightest emotional participation, just as had already happened in the Roman painting depicting the martyrdom of Peter, where the executioners seem focused only on the material operation of raising the apostle’s cross, without an awareness, or at least cognisance, of their act.

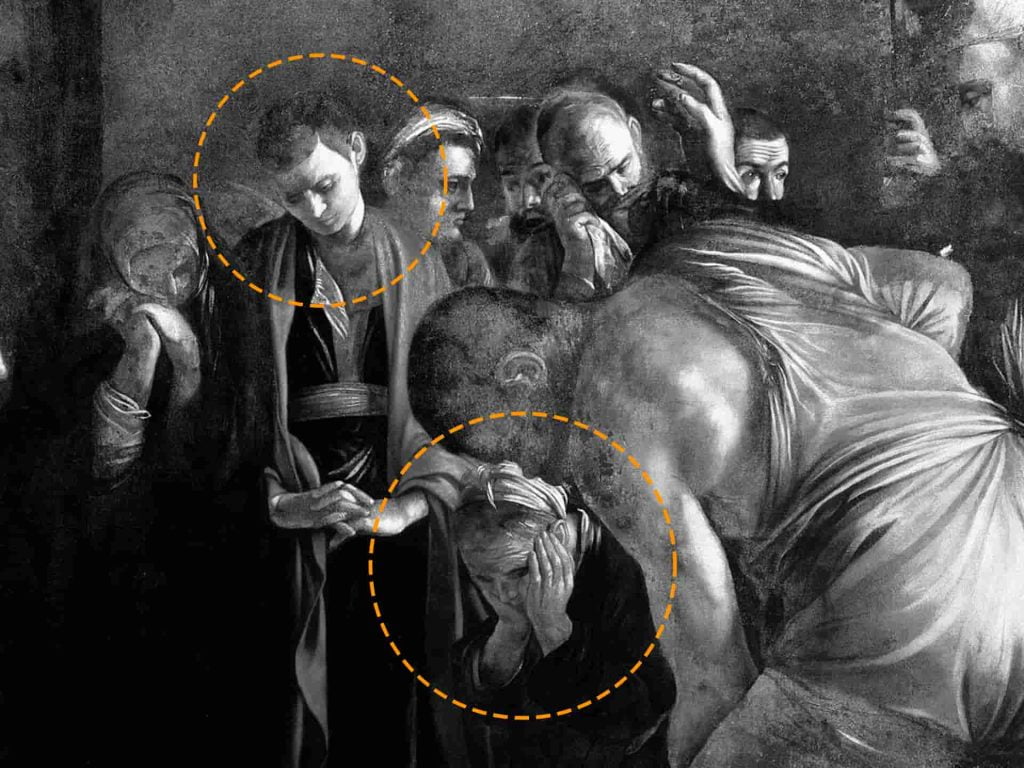

In the Syracusan canvas, rather than expressing pain, the characters surrounding the blessing bishop display a calm displeasure mixed with resignation. The feelings appear so superficial that they cause most of the characters to lose their individuality and definition in the composition.

The only person who seems to experience genuine grief is an elderly woman, kneeling beside Lucy’s body, who, in disbelief and dismay in the face of the saint’s violent death, has her hands on her face, with a gesture very similar to one already proposed by Caravaggio in a female figure present in the scene of the ‘Beheading of the Baptist’.

Elderly woman displays genuine grief amid stoic onlookers, mirroring a similar pose in Caravaggio’s ‘Beheading of the Baptist.

Caravaggio, always free from any pre-established schema, only cites himself in his works of artistic maturity. Hence, Lucy’s body, devoid of vital strength, is depicted without the serene composure, ideal and idealised, of the martyrs present in the works of other artists, but with the exposed shoulder and the same abandonment, the same dramatic truthfulness of the Virgin in the canvas ‘Death of the Virgin’.

Just as the events of the artist’s private life reveal more than one Caravaggio, his works exhibit the same versatility. It is as though within a single man, a single body, several souls and personalities find space, capable of generating beauty and death with the same intensity.

Caravaggio, in his art, never looks outside himself but draws from his own soul, his own feelings, his own art. Each of his paintings not only tells the stories of its characters but becomes a clear reflection of the evolution of the author’s character and experiences.

Caravaggio’s flight and torment are not only manifested in the repetition of beheading scenes, but also find expression in the new way of presenting and perceiving light, the principal element and guiding thread of his entire artistic production.

Unlike his earlier art, where light and shadow were clearly separate, here they blend together. This shift in lighting style mirrors Caravaggio’s personal struggles, creating an atmosphere where life and death feel equally present.

Compared to the Roman works, the light in his last works loses intensity, becoming dramatically and inexorably rarefied, as if it were no longer distinct and opposed to darkness.

In Caravaggio’s early works, shadow and light, even if clearly defined and in a certain sense distinct, were at each other’s service. In the artist’s final works, however, these same elements become one, merging into a single entity, where it is not evident where the shadow gives way to light.

This is much more than an expressive technique; it is the reflection of a soul where the immediacy of life and the absolute certainty of death coexisted with equal strength and urgency.