Despite relentless conquests, the struggle for Tibet’s sovereignty extends beyond the protection of its heritage; it’s a fight for the nation’s very spirit, enduring as the mountains that embrace it.

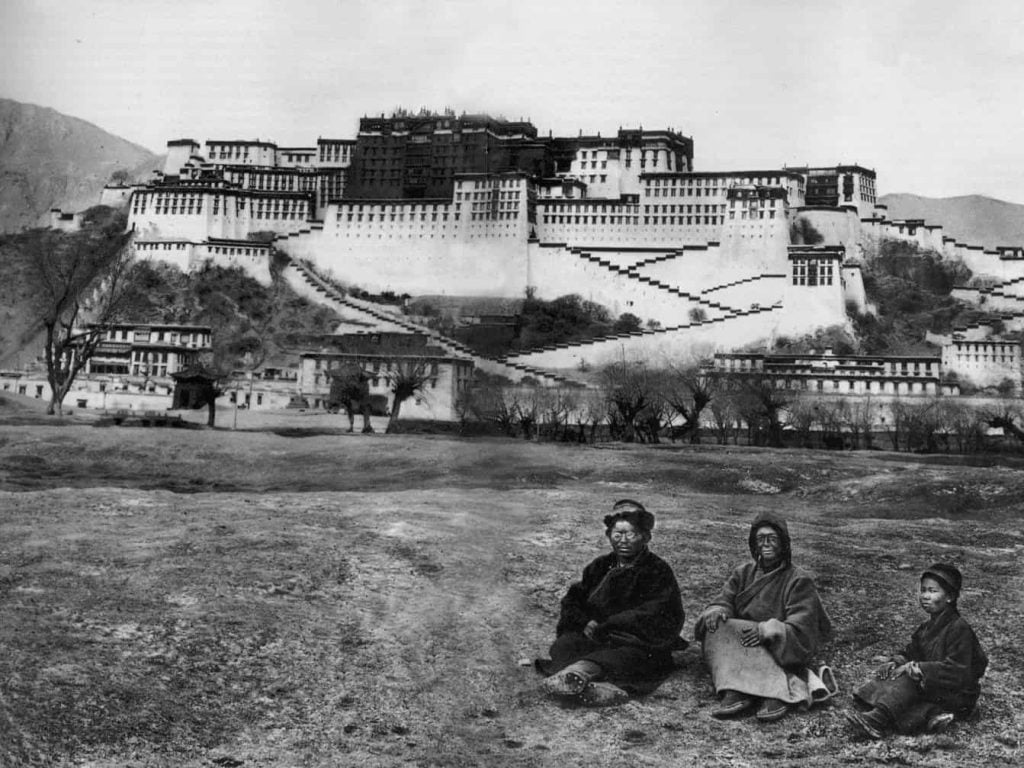

Shrouded in the mystique of the high Himalayas, Tibet presents a realm of stark duality. Its tranquil scenery and the hallowed quietude of temples whisper tales of deep-rooted spirituality. Yet, beneath this cloak of tranquillity, a spirited narrative of national identity and governance grapples with forces of external influence and internal doctrine.

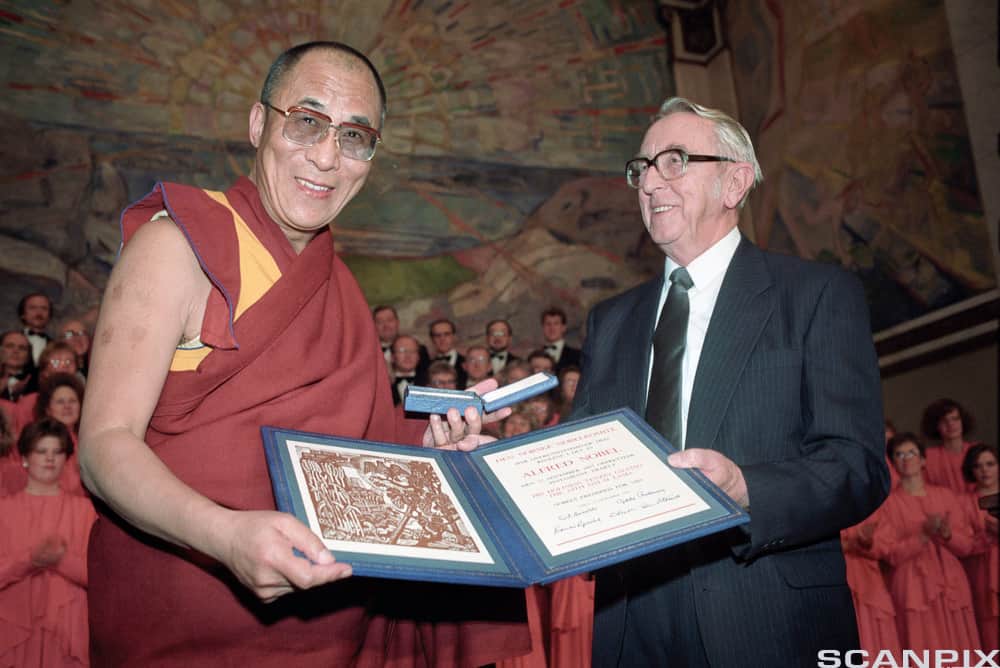

The story of Tibet is not solely one of idle meditation; it is equally about active engagement in the arduous task of nation-building. Here, the Dalai Lama stands not only as a spiritual zenith but also as a symbol of the unyielding campaign for cultural and political self-determination. This is a journey into the heart of an aspiring nation, where the pursuit of peace is as much an internal journey as it is a political quest.

From Mongol rule to the Qing dynasty

The historical backdrop of Tibet spans from Mongol rule to the Qing dynasty. Featuring a range of actors from the incursive Mongols to the remote Manchus, Tibet created its own history. During the 13th and 14th centuries, Tibet first engaged significantly with external powers, initiated by the Mongols who introduced a layered governance structure, transcending the conventional conqueror-subject dynamic. Tibetan leaders displayed diplomatic finesse, trading political allegiance and spiritual blessings for Mongol protection. This strategic barter allowed Tibet to maintain a level of autonomy, even as the Mongol Yuan dynasty increasingly adopted Chinese customs and administrative practices within their broader empire.

However, the lustre of this alliance waned as the Mongol Yuan dynasty, beleaguered by onerous taxation and class strife, entered its decline. The heirs of Kublai Khan, the Yuan dynasty’s founder, sinicised and estranged from their nomadic roots, lost the support of other Mongol dominions. Coupled with natural disasters, these factors signalled the dynasty’s end, enabling Tibet’s reclamation of autonomy.

From the mid-14th century onwards, Tibet enjoyed nearly 400 years of de facto independence, navigating through political fragmentation. It was during this period that the Dalai Lama emerged as a pivotal figure, with Mongolian patronage, particularly from leaders like Abtai Khan, who championed the Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. This sect, distinguished by its scholarly rigour and monastic discipline, established the Dalai Lama as a spiritual and political linchpin, laying the foundations for governance that intertwined religious leadership with secular authority.

Fast forward to the 18th century, the Qing engagement marked a nuanced chapter of influence, where Tibet’s theocratic leadership, while respected, was subtly overseen. This arrangement persisted until the Qing’s early 20th-century demise, which catalysed Tibet’s pursuit of heightened sovereignty and the continuation of its nation-building journey.

The role of Buddhism in governance

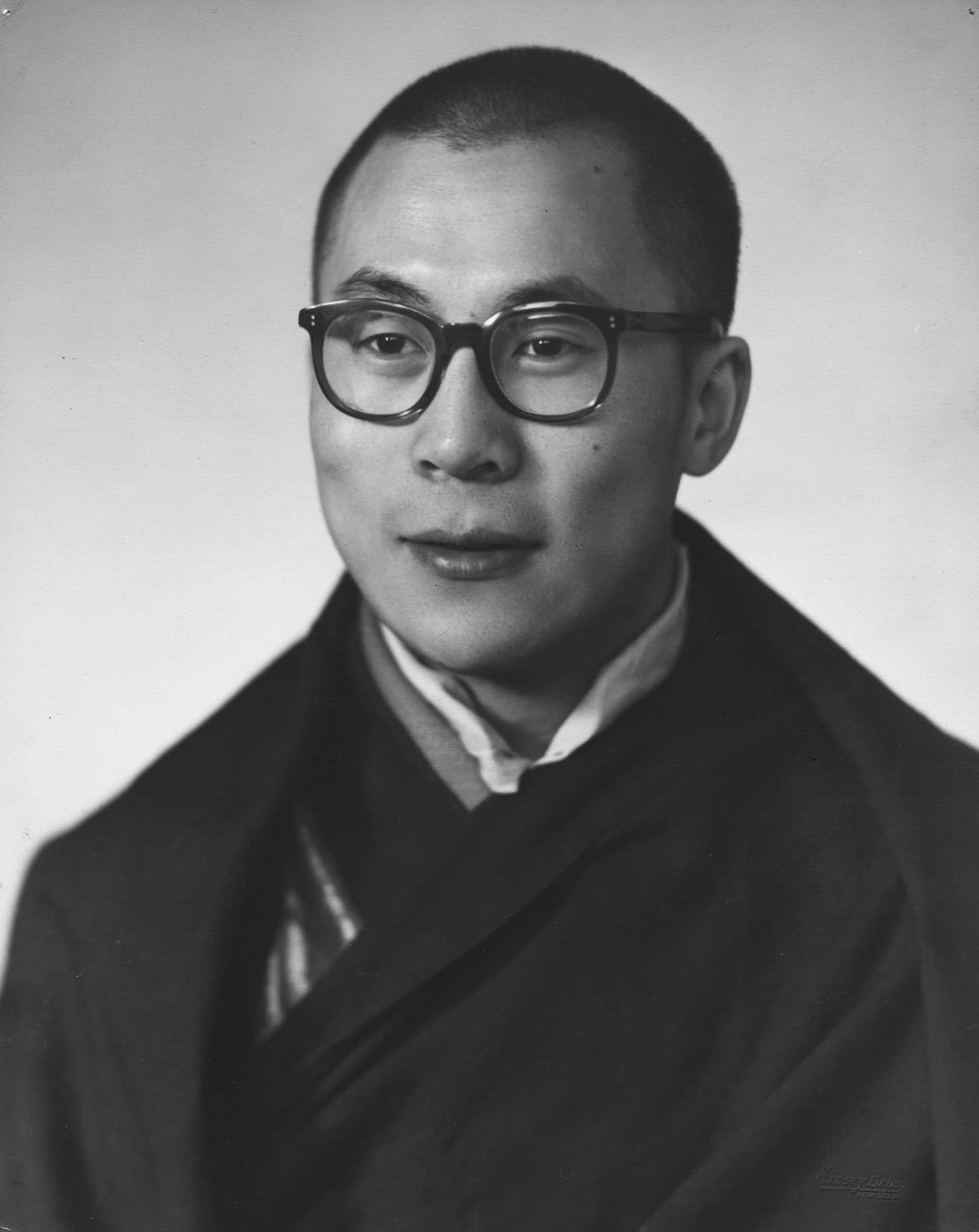

Tibet has maintained a strong link between its Buddhist principles and political leadership. The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, rose to eminence not through a political ceremony but through spiritual recognition, honouring the Tibetan Buddhist conviction that Dalai Lamas are reincarnated. These figures are venerated as the human form of Avalokiteśvara or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of compassion and Tibet’s guardian deity.

At this confluence, the Dalai Lama embodies both spiritual sway and secular authority, bestowing upon Tibet a distinctive form of statehood. Monasteries, vibrant hubs within this system, serve not solely as sanctuaries of faith but also as centres for learning, health and civil administration, all infused with Buddhist philosophy. With the Dalai Lama at the forefront, this theocratic foundation has sculpted Tibet’s cultural and philosophical identity.

This model of government has not been without its detractors. Critics, including those from the People’s Republic of China who seek to justify their rule, have labelled it as a feudal structure dominated by monastic elites. Such perspectives argue that it curtailed political and religious diversity, leading to periodic sectarian tensions. Nevertheless, the Tibetan government-in-exile maintains that Tibet harbours an innate capacity for self-reform and argues that, in the absence of external interference, an alternative historical path could have unfolded.

The advent of Chinese rule in the twentieth century heralded a significant ideological transition within Tibet. The introduction of a secular, communist system by the new authority was a striking contrast to the spiritual and theocratic fabric that had long been the cornerstone of Tibetan identity.

The rise of the Chinese Communist Party

At the waning of the 1940s, Mao Zedong’s Communist Party seized control, compelling the People’s Liberation Army’s advance into the mountain stronghold of Tibet. With its modest defences and lack of global allies, Tibet stood exposed to the relentless march of Chinese dominion. The Chinese incursion into Chamdo in 1950 elicited Tibet’s plea to the United Nations via El Salvador, only to meet a chorus of strategic silence. India advocated for peace talks, whilst Russia, the United States and the United Kingdom echoed China’s sovereignty claims over Tibet. The international community’s unequivocal stance left Tibet’s appeal adrift in a diplomatic abyss.

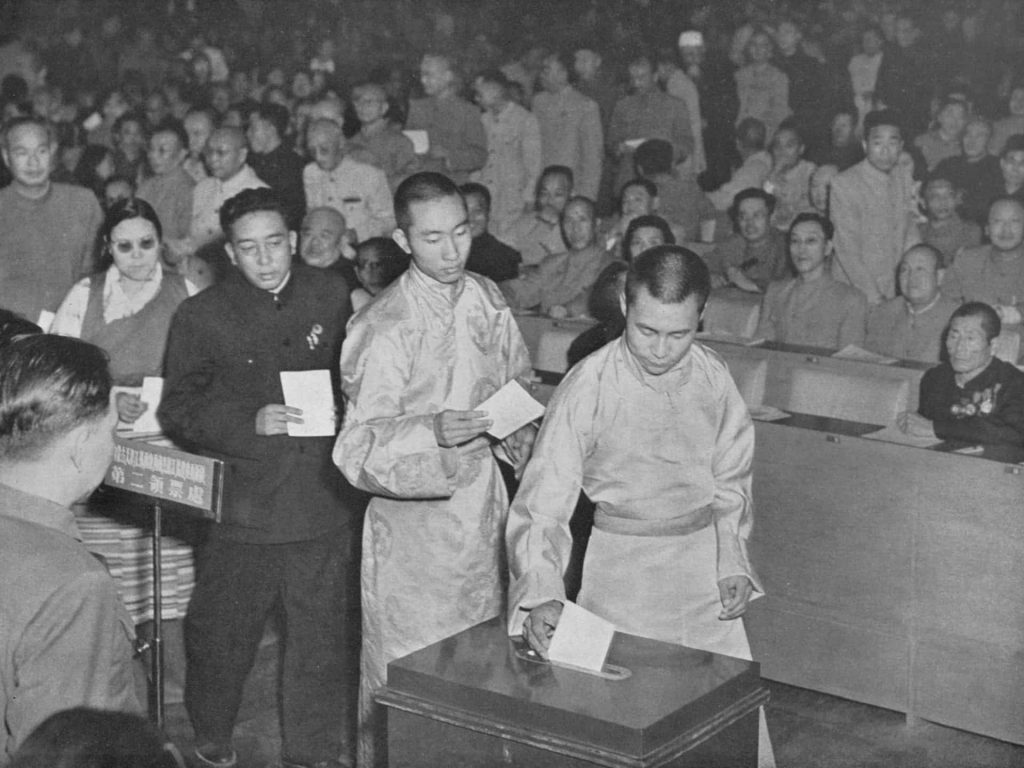

Amidst this international recognition of Chinese sovereignty, the Seventeen-Point Agreement was forged, signalling the end of Tibet’s nation-building aspirations. This agreement, promising autonomy but enforced by Chinese oversight, effectively dismantled Tibet’s sovereign structures. It absorbed Tibet’s military into China’s, transferred international negotiations to Beijing and mandated that any Tibetan reform occur under a Chinese-led committee. Thus, the agreement laid a complex foundation that complicated Tibetan self-identity and nationhood.

Subsequently, the 10th Panchen Lama, traditionally integral to confirming the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation and the second most prominent figure in Tibetan Buddhism, expressed his public endorsement of the agreement, while the Dalai Lama offered his acknowledgement with reservations. However, the semblance of accord was fleeting, as disparities between the promised self-rule and the reality of Chinese control became evident, undermining the agreement’s foundation.

The tumult of 1959, with its brutal suppression of the Tibetan revolt and the mass casualties it wrought, exposed the profound rifts within the region. The unrest precipitated the Dalai Lama’s escape to India on 3 April of that year, inaugurating the Tibetan diaspora and transforming Dharamshala into a sanctuary for those fleeing Chinese rule. The Cultural Revolution, starting in 1966, marked a crusade against ‘counter-revolutionary’ elements, a purge that razed monasteries and sought to erase Tibet’s cultural identity, prioritising Mandarin and diluting local customs.

A pinnacle of this cultural domination was Beijing’s interference in the selection of Tibet’s most sacred leaders, the Dalai and Panchen Lamas. The disappearance of the 11th Panchen Lama, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, following his endorsement by the Dalai Lama in 1995, throws into sharp relief China’s iron grip on Tibet’s religious heart. Invoking the Qing Dynasty’s golden urn lottery, a ritual that randomly determined the selection of significant lamas by drawing lots from a golden urn, Beijing insists on its right to direct these sacred choices, reinforcing its sovereignty despite the contentious nature of Tibet’s absorption into China.

A peaceful nation in the making

Peace stands as the cornerstone of Tibet’s aspirations for nationhood. The Dalai Lama’s Middle-Way Approach offers a vision of self-governance within the framework of China, aiming to protect Tibet’s cultural and spiritual identity while respecting Chinese sovereignty. This vision seeks an equilibrium, with Tibetans overseeing their own laws and safeguarding their environment, and the Dalai Lama leading the dialogue with China. Yet, China perceives this as a cloak for separatism, a challenge to its territorial integrity.

The resilience of the Tibetan people, however, serves as a counterpoint to this impasse. Tibetans have harnessed their profound cultural and spiritual beliefs to maintain a steadfast, peaceful opposition. As they navigate through an era where digital platforms break barriers, their cause gains visibility and resonates with a global audience. The diaspora, too, plays a pivotal role, casting light on injustices and rallying support across continents, thus creating a bridge between the domestic struggle and international advocacy.

Yet, international engagement with the Tibetan cause is characterised by a complex and often inconsistent stance. Western support, most notably from the United States and the United Kingdom during the more strategic Cold War period, was ephemeral and, upon closer examination, more self-serving than supportive of Tibetan self-rule. The United Nations, for its part, finds itself paralysed by the interplay of international politics and China’s assertive presence, resulting in a conspicuous silence that mirrors the prevailing international disposition—a reluctance to upset the status quo and formally recognise Tibet’s sovereignty aspirations.

Against such a backdrop, Tibet’s narrative weaves through the corridors of power and into the annals of heritage and belief. The possible cessation of the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation line is not merely a religious watershed; it is a potent symbol of Tibet’s unfolding story. This potentiality poses an existential question for Tibet’s identity, hinting at a future unmoored from religious tradition, an identity possibly reimagined through the lens of secular modernity.

The story of Tibet, while anchored in history, remains dynamic, embodying the nuances of peaceful nation-building in a world frequently swayed by military might. The Tibetan approach offers an example of peaceful resistance and cultural resilience. The outcome of Tibet’s pacifist struggle will stand as a testament to the power of nonviolent action, potentially setting a precedent for other emerging nations.

Tibet’s evolving journey speaks not only of preserving its own cultural heritage but also of sustaining a principle: the enduring nature of a nation’s soul, as steadfast as the mountains that embrace it.