Unveiling the emotional tension in Caravaggio’s ‘Judith and Holofernes,’ a dramatic narrative of good versus evil comes to light through distinctive stylistic elements.

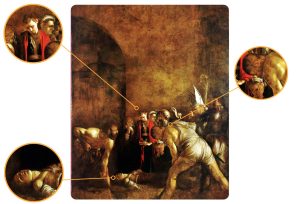

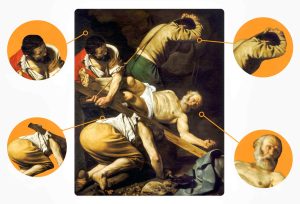

The repetition of distinctive stylistic elements helps art scholars, when necessary, to identify and recognise the authors. In the case of Caravaggio, the most frequent distinctive elements are different: the stroke of the drawing; the choice of the same models for the various characters; the way of interpreting the colours; the contrast between shadow and light…

Yet what in my eyes makes Caravaggio’s hand truly unmistakable, even more than the presence of these objective stylistic elements, is the emotional tension that shines through the faces of the characters who, in most cases, tell us about the eternal conflict between good and evil that has always accompanied man.

This internal battle is the element that shines through in the gestures and faces of the work “Judith and Holofernes” by Caravaggio, also known as Michelangelo Merisi. The canvas was created between 1598 and 1599 on commission from Count Ottavio Costa, Merisi’s patron for a period.

The theme of the painting certainly does not stand out for its originality compared to what was the artistic panorama of the period. In fact, several artists, before and after Caravaggio, have recounted the deeds of the Jewish widow Judith who, to save her people from foreign domination, did not hesitate to kill the Assyrian leader Holofernes by beheading him while asleep, after having gained his trust.

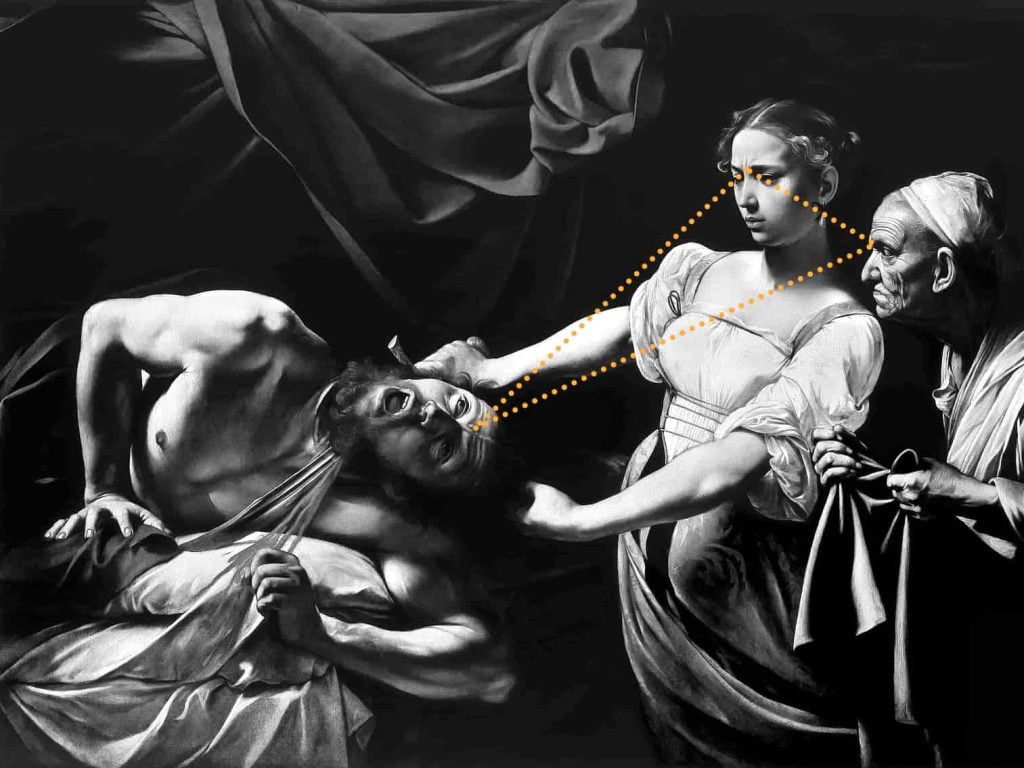

This canvas depicts the most dramatic moment when the biblical heroine, armed with a scimitar, a weapon chosen by the painter because of its oriental origin, begins to cut off the head of the Assyrian enemy. Beside her, as a witness to the scene, is her servant Abra, ready to collect the sad trophy of the severed head in a basket covered with a cloth, which will then be delivered to the Jewish people.

The dark background, as in other cases, is used here to underline the drama of the moment. The background shadow is interrupted only by a light source coming from the left. The colours chosen, to contrast with the darker areas, are shiny and animated to enhance the physical as well as the interior characteristics of the three painted figures.

The triangular construction, which perfectly balances the scene, sees a Holofernes able to support himself on his arms despite the power of the blow received. In his eyes you can still read the pain and amazement in front of the strong and decisive gesture inflicted on him by the woman who, thanks to her beauty and the power of her prayers, had deceived him and the Assyrian people.

In the centre of the painting, Judith, depicted with a white dress and uncovered arms, completes her plan of death and salvation.

The decisive movement of her arms clashes with the expression on her face, which tells us about her contrasting feelings: pride and disgust because she is aware of the strength and consequences of the gesture she first planned and then carried out.

Next to Judith, Abra’s features are very different from those of her mistress; she is old and devoid of beauty. The style of the drawing, the different choice of skin colours, testify not only to the age difference between the two women, but also to the different depth and nobility of their feelings.

The various cloths depicted in the scene, which serve different functions, are so soft and delicate, that they seem real. We see them as Caravaggio saw them, choreographer and set designer of scenes even before embarking on his paintings. The cardinal red drape that overlooks and encloses the action narrated is the same one used later in the painting of the Death of the Virgin, confirming the scenic construction prior to each of the painter’s works.