In a world beset by rising nationalism and a chronic disregard for global responsibility, could a world constitution steer us towards peace and prosperity?

First Contact

Isaac Newton famously said: “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Sadly, society is where it is today because most people have stood on the shoulders of ogres. The past sticks to us like shit on a shoe and we have become so accustomed to the foul smell, that rather than scrape off the dung, we wallow in it.

Picture this: planet earth in the 21st century, but one that had never witnessed the advent of humankind. Then, suddenly, it is discovered by an alien species much like our own. Before long, the planet is plundered, ravaged and abused. Life forms are enslaved, tortured and killed for entertainment, fashion and culinary delights, their habitats destroyed; forests are cut down; and rivers and seas polluted beyond recognition, as are the skies. Finally, having exhausted every possible resource, the alien species moves on, like a plague of locusts, to its next quarry.

Apart from two crucial differences, our reality is more or less the same. The obvious difference is that, as the saying goes: “There is no planet B.” The second difference is that our exploitation was not sudden. If it were, we may have been able to recognise it for what it was: the vilest abuse of power and disregard of all responsibility. We built our own hell brick by brick, cheered on by tradition, by religion and by a chronic reluctance to stop, reassess and change course.

Though tragic, that is still just half the picture. At least the alien species mentioned above did not violently turn on itself in the process of its exploits: we regularly do. Nations turn on nations, people turn on people, rulers turn on citizens. As for the laws we instituted, they help. However, as the sixth century BCE Scythian philosopher, Anacharsis, said, reflecting on Solon’s precepts: “These decrees of yours are no different from spiders’ webs. They will restrain anyone weak and insignificant who gets caught in them, but they will be torn to shreds by people with power and wealth.” One could add that nations barely even notice them.

Where to begin?

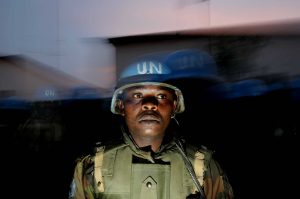

As we will discuss later, a global constitution would address all these problems. To date, however, all we have are laws, international laws and the UN Charter. Nevertheless, judging from the state of the planet today, one does not have to be a genius to realise that these are far from effective in fostering peace and respect for the planet. By its very nature, national or local legislation is limited in relation to global issues.

International laws, on the other hand, are always watered down by national and corporate interests, even when faced with life-threatening issues like climate change or disarmament. Moreover, the collective will to enforce them is tepid at best; while some of the more comprehensive pronouncements, such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), are vague and not even legally binding.

This leaves us with the UN Charter. Adopted in 1945, the Charter was a missed opportunity to establish a firm framework for global governance while at the same time respecting the individual leanings of nation states. It could have been developed as a global constitution with inviolable ethical norms that all member states would have had to adhere to, or face forfeiting their membership if they did not.

However, while the UN Charter highlights the main objectives of the United Nations, such as the maintenance of international peace and security, the promotion of human rights, the development of friendly relations amongst nations, and the cooperation required in solving international problems, it does so as a sort of wish list for the organisation as a whole to strive towards. Its focus, therefore, is setting out the parameters, structure and functions of the UN, including the General Assembly, the Security Council, the Secretariat and other specialised agencies.

The virtues of a constitution

If we examine constitutions from a national point of view, we can easily conclude that they are an asset, despite certain shortcomings. Unlike general legislation, national constitutions are formal documents that establish the fundamental principles, structures and operations of a state. They typically outline the rights and freedoms of individuals, the powers and limitations of government institutions and the processes for making and enforcing laws. They are generally secular in nature, designed to provide a framework for governance that applies to all citizens regardless of their religious beliefs. Constitutions are therefore the guiding principles on which specific laws should be founded.

Owing to the sophisticated and structured nature of a constitution, some nations have evolved without them. In fact, the first known written constitution is generally believed to have been the Constitution of Medina, which was drafted as late as the year 622 CE (or 1 AH – After Hijra) in the city of Medina (then known as Yathrib) in present-day Saudi Arabia. Unlike Sharia law, it was a social and political contract between various tribes and groups in Medina, including Muslim and non-Muslim communities and its purpose was to establish peace, stability and cooperation amongst the diverse population of the city.

The United Kingdom is a prime example of a country or political entity without a written constitution. Instead, its constitutional framework is based on a combination of statutes (laws), common law principles, court decisions, and constitutional conventions that developed through the course of its history with some notable and defining events such as the Magna Carta of 1215, the English Civil War in the 17th century and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Whilst the absence of a rigid, codified constitution provides flexibility for the UK’s political system, there are inherent dangers in the freedom it allows Parliament, which can pass laws without constraints or accountability to ethical norms.

In June 2023, the Scottish Parliament published its proposed constitution for the eventuality of an independent Scotland, titled: Creating a modern constitution for an independent Scotland. First Minister Humza Yousaf’s presentation of the Paper highlighted, among other points, the flaws in the UK political system due to its lack of a constitution:

“This makes it a global outlier among modern democracies. For example, all member states of the European Union have written constitutions. Not having one, and relying on Westminster supremacy has real consequences. We’ve spent the last decade looking on as the UK Government undermines constitutional principle, after constitutional principle, with very little that anyone can do about it to challenging them or holding them to account. That would not be possible in a country with a codified, written constitution that sets what the rules are, and importantly, and crucially sets out what people can do to ensure governments and politicians adhere to them.”

Of course, as “a standard below which no government should ever fall” (Yousaf), constitutions need to focus on inalienable rights and responsibilities.

Caveats when drafting a constitution

Before highlighting the benefits that a global constitution would bring, it is worth noting some of the pitfalls when drafting constitutions in general. The first is the danger of being too specific. The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, for instance, is a typical example of a flawed constitutional element. The Second Amendment states: “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” Whilst the right to self-defence is a fundamental human right, the conclusion that this could involve every idiot being armed to the hilt, is not.

Another danger stems from complacency. As the above point highlights, as we evolve, so will our constitutions need to, in order to keep pace. This is particularly relevant in today’s rapidly changing world with new threats and opportunities, like Artificial Intelligence, emerging with increasing frequency. Hence, it is important for constitutions to include an amendment process that outlines the procedures and requirements for updating the constitution. This may specify the majority or supermajority needed for amendments and any special procedures for constitutional revisions. Often this revision would involve a referendum or similar proceedings.

Sadly, in the past few years we have seen how autocrats all over the world have exploited and manipulated such processes to change their country’s constitutions in order to give themselves even more power: Erdogan (Turkey: 2017), Xi (China: 2018), Sisi (Egypt: 2019), Putin (Russia: 2020), Japarov (Kyrgyzstan: 2021), Saied (Tunisia: 2022) … The trend is alarming.

Whilst no constitution is entirely immune to challenges or attempts at usurpation, maintaining a healthy democratic system is fundamental to upholding the principles and values enshrined in the constitution. Safeguards should include separation of powers, checks and balances, the protection of fundamental rights, unhampered media and, most importantly, popular participation, education and engagement. Points that have been carefully eroded by the above-mentioned despots. The rights our forbearers fought for at such a huge cost are often being squandered by apathy and an addiction to bread and circuses. In other words, we need to be vigilant, or our nation may be next, if not already compromised. Trump’s words following Xi Jinping’s power 2018 grab spring to mind: “Maybe we’ll give that a shot!”

The Global Constitution

So, having said all this, it is clear that a global constitution can help by setting a standard below which no nation should fall. These standards will cover human rights, an international rule of law, mechanisms for resolving conflicts peacefully, a framework for global governance, and common standards and regulations in areas such as trade, environmental protection and public health. All these areas require global approaches and solutions.

If human rights were human, then they would have to apply to everyone; everywhere.

Let us take human rights, for instance. If human rights were indeed human, then they would have to apply to everyone; everywhere. Currently, we live in a world where only national rights exist. If you are gay in Uganda, they can legally kill you for it; if you are a migrant fleeing war on your way to Europe, they can let you drown. Of course, some human rights are legally abused everywhere, like infant male circumcision, which to date is allowed in every country on the planet, or unreasonable travel restrictions, which often leave people trapped within their own borders for their whole lives.

A global constitution can clarify human rights and stipulate that they should be universally protected. The obvious problem is that consensus by all nation states would be impossible in our current situation. Most countries are happy with rigid borders; many relish in criminalising LGBTQ+ rights; some are determined to brainwash their people into a quasi-vegetative subservience… A lack of consensus, however, will never make abuse right.

This therefore begs the question: Who then will produce such a constitution? Just as religions sprung from ideals, despite the recognised establishment, and irrespective of whether people wished to follow them or not, so now the ethical vision has to present itself in its own right. Waiting for the powers that be to agree on a set of inviolable norms, would mean waiting forever, but having the vision there, a vision that gradually attracts people of good will and eventually nations, is the best chance of jolting the course of events.

The good news is that much of this groundwork has already been done. Academics have been writing about global constitutions for years, while a number of organisations with substantial global membership are dedicated to this and have produced drafts that only need updating and refining. One such constitution is The Constitution for the Federation of Earth, developed by successive constituent assemblies over the course of about 23 years, from 1958 to 1991. As well as UN-aligned, organisations that have been focussing on a global constitution include the Earth Constitution Institute, the World Parliament and the Young World Federalists.

Some nation states have toyed with the idea of accepting such constitutions, but backed off for one reason or another. The solution is for all these organisations to pool in together and become a force to be reckoned with. Only then will we achieve more visibility and clout.

As the global constitution becomes increasingly established, the holy grail of enhanced global citizenship can then be achieved, emphasising the rights and responsibilities of individuals as members of the global community. This should promote global values, such as tolerance, equality and sustainable development, and encourage individuals to engage actively in global issues.

A global constitution is not a silly and unattainable utopic vision; on the contrary, it is the only vision that can stop us from our current ominous trajectory and from humanity tearing itself apart. As Albert Einstein wisely noted: “There is no salvation for civilisation, or even the human race, other than the creation of a world government.”

- If you have any ideas on how we can build a united front for the promotion of a global constitution that cannot be ignored, please get in touch with us.