Exploring the concept of the ‘New Soviet Man’ and how a modern-day equivalent could promote world federalism and overcome nationalism.

As an old millennial having experienced childhood in the nineties, my generation grew up with the quintessential strongmen movies personified in protagonists like Rocky Balboa, Ivan Drago and Apollo Creed, as seen in the Rocky franchise.

In Rocky 4, Dolph Lundgren portrayed a rather intimidating antihero; an opponent more machine than man. My generation remembers a world before it was possible to Google our curiosities away into the ether of the internet. Exposure to the world in terms of different cultures, languages and ways of life was primarily derived from movies like Rocky 4. Ivan Drago, Rocky’s deadly opponent having killed Apollo Creed in the boxing ring, seemingly revisited the literal definition of the New Soviet Man.

Based on Marxist-Leninist propaganda officially sanctioned by the Soviet Communist Party, the New Soviet Man was described as the quintessential man of the future. He was a selfless, educated, healthy and iron-willed true believer of the Soviet Communist Experiment liberated from the primitive superstitions of the past.

Komsomol pioneers were taught to emulate the image of the New Soviet Man as a high example of what it meant to be civilised in the atomic age. The imagery associated with such a patriarchal figure was assumed to be culturally eternal: the existence of the Soviet state depended on raising New Soviet men to achieve world communism.

The lowering of the Soviet flag for the last time on December 25th, 1991 reminded us that any ethos for civilisation cannot be achieved by totalitarian propaganda alone. What was the New Soviet Man beyond an existential allegory of perfection that contradicted the very existence of the empire it was supposed to serve? This begs a digressive question: what came first, the nation or the idea that bore it into a conceptual reality? Is ethnology the science of matter-of-fact anthropological realities evolved over geographic circumstance and sociological happenstance?

The United States and the former Soviet Union shared one existential commonality: they were both superstates based on a diabolically opposed blueprint of ideas. The idea of a nation is validated by its supporting philosophy of civilisation.

The end of the Cold War created a multipolar geopolitical power vacuum. It rapidly became evident that a world of superimposed unilateralism is one where realpolitik is applied in lopsided absolutes. The tribalisms of antiquity are representative of the nationalisms of today. It is for this reason that we have global governance, but no world federalism.

Historians often argue history repeated is history forsaken. Perhaps the repetition of history can be seen as an opportunity to get history right? The question is: is the United Nations too big to fail? How many activists prospecting United Nations reform have proposed a glasnost and perestroika parallel to Cold War history? To many, the United Nations is seen as an organisation of working disconnects and literal contradictions where eager diplomats seek to make self-serving zero-sum legacies passively.

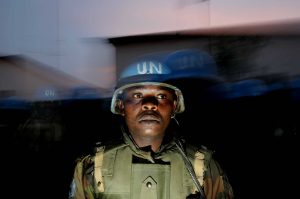

The United Nations could restore relevance and credibility to generations X and Y by offering a consciousness of ‘supracultural awareness’ to the abysmal war cries of nationalism. How can world federalism be sustained as a multicultural reality under the auspices of a ‘New International Man?’ Is there such a thing?

In many ways, Greek mythology is illustrative of man’s hopes, desires and sufferings. Each deity of ancient polytheistic Hellas subscribes to an allegorical attribute of human nature. One of the most recognisable Titans is Atlas. He is no God. He is an eager everyman bearing the weight of the world on his shoulders with hopes of high posterity.

A New International Man is an equal-opportunity civilisation builder.

The New International Man sees no divisions in nations. He only sees peoples, cultures and the infinite potential of man to build a world that could be as opposed to what it has become. He is not an empty-headed ideologue disconnected from reality. He is a big picture thinker and centenarian planner. Beyond history, he views our future as our common heritage. He is dedicated to eliminating weapons of mass destruction, biological and chemical warfare. He sees peaceful potential for everything, but is no pacifist, realising force is at times necessary to maintain peace. His mightiest sword is the pen. He believes every race, nation and culture of the world has new international players to add to the perpetual discourse of world peace.

Yet, can world federalism become a cultural phenomenon personified in the idea of the New International Man?