Dive deeper into the history and symbolism of early Christian art with our analysis of the ancient Nativity Fresco in the Catacombs of Santa Priscilla, Rome.

Over time, I have learned that when it comes to art it is not necessary to be original at all costs, I simply understood that I have to write what I think, in the way and in the times that most belong to me.

I certainly would not try to be original and captivating during Christmas, a time that most of all tells us about traditions and the need to go back to basics.

It is precisely this simplicity and expressive spontaneity, combined with my personal need to go back to the origins, that guided me in choosing the nativity that we will examine as a symbol of this Christmas: the one preserved in the catacombs of Santa Priscilla in Rome, which it is the oldest scene reproducing Mary with the newborn baby Jesus that has come down to us.

Catacombs are underground tombs used by early Christians for burials and rituals. The catacombs that house this fresco are named after Priscilla, a woman from the Acilii family, also mentioned in Roman martyrology for having donated land to the Christian community so that catacombs could be located there.

The catacombs of Priscilla, which were dug out between the 2nd and 5th centuries, are certainly the best known of all the underground early Christian cemetery environments. They are also the ones with the most martyrs and pontiffs buried there. Precisely because of this significant presence in antiquity these catacombs were called “regina catacumbarum”.

The paintings that decorate the walls of the numerous tunnels (the catacombs extend for more than thirteen kilometres) are varied. Some frescoes, although deprived of their original religious meaning, recall the ancient pagan tradition; others instead testify quite explicitly to the Christian cult and the Old Testament.

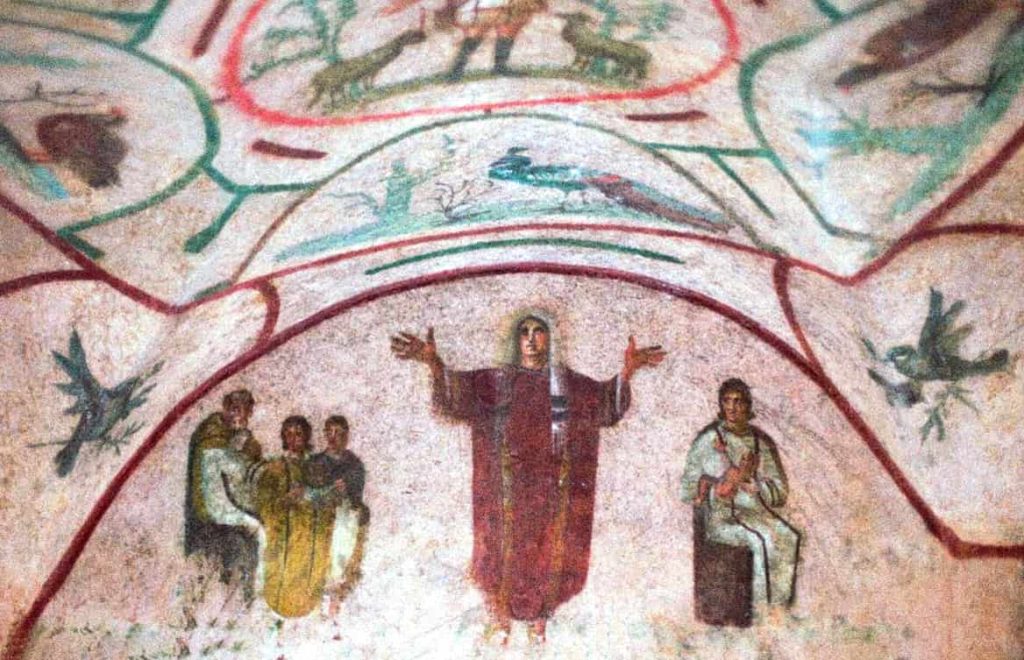

The fresco reproducing the nativity is on the ceiling of a niche that housed the body of a martyr; therefore a burial that was certainly very popular in antiquity.

The position of this niche in the initial part of the cemetery and the drawing and painting characteristics of the fresco, suggest a dating that places it within the first half of the third century.

Although part of the drawing has been lost, all the elements and subjects that help us to identify and read the scene are evident, including some natural decorations such as branches and flowers that frame the subjects.

Mary and her child

On the observer’s right we see Mary seated with her Child in her arms. The Virgin’s robe, a short-sleeved tunic, recalls the style of Pompeian paintings, even the natural process of colour degradation seems to evoke the nuances of Campanian paintings.

Mary is depicted with her head covered by a veil, a symbol of divinity or consecration to divinity. Despite the state of conservation of the fresco, we note a gesture of the subject exempt from subsequent intellectual and theological settings.

Mary affectionately supports the little one in her arms like any mother, without symbols or movements typical of later depictions that suggest an awareness, or at least a premonition, of the Passion.

The child is depicted with his torso flexed to give an idea of movement. This twist, together with the mother’s caring attitude, removes the static nature of the scene.

The Orans

The person standing in the middle, depicted in the “orans” posture, is thought to represent a consecrated virgin who was buried in this tomb. The scene in the background to the left is believed to depict her consecration to a life of virginity. The figure is holding a veil and is being admonished by the bishop, who sits in a cathedra and is assisted by a deacon, pointing to the Virgin Mary as a model for her life.

The man on the left

This feeling of dynamism is almost completely missing in the character on the left of the observer. I am referring to a male subject, depicted in a lateral position, pointing to the child Jesus and his mother. Although the subject appears somewhat static, a different pictorial purpose has been achieved here.

The man is portrayed with such proportions compared to those of Mary as to be distant from her and is useful in as much as he adds a different dimension to the story. In fact, this male figure suggests a prophet in the act of announcing, prophesying, the advent of the Messiah.

It is not easy to speak with certainty of the identity of this man, scholars have proposed various hypotheses and the one that is certainly the most plausible is the one that identifies him with the prophet Balaam whose very interesting story is present in the book of Numbers.

Balaam was a good man, chosen by the king of Moab to curse and block the Jewish people on their way to the Promised Land. The man tried to cast the curse three times without success and ended up becoming a prophet instead.

The part of his prophecy that appears to be alluded to here says: “I see him, but not now, I behold him, but not closely: a star rises from Jacob and a sceptre rises from Israel” (Numbers: 24.17).

The “far” position with respect to Mary and the hand stretched out to indicate a star, placed right above the Virgin and the child, seems to confirm the identity of the prophet with Balaam. The conceptual complexity of the prophecy goes hand in hand with the simplicity of its pictorial representation. What the prophet saw was drawn, nothing more, nothing less, without hidden symbols or concepts.

The Epiphany

The star presented by the scriptures to indicate the birth of the Messiah is also present in another fresco in the catacombs that depicts another moment that has always accompanied the paintings that celebrate this particular period of the year: the Epiphany.

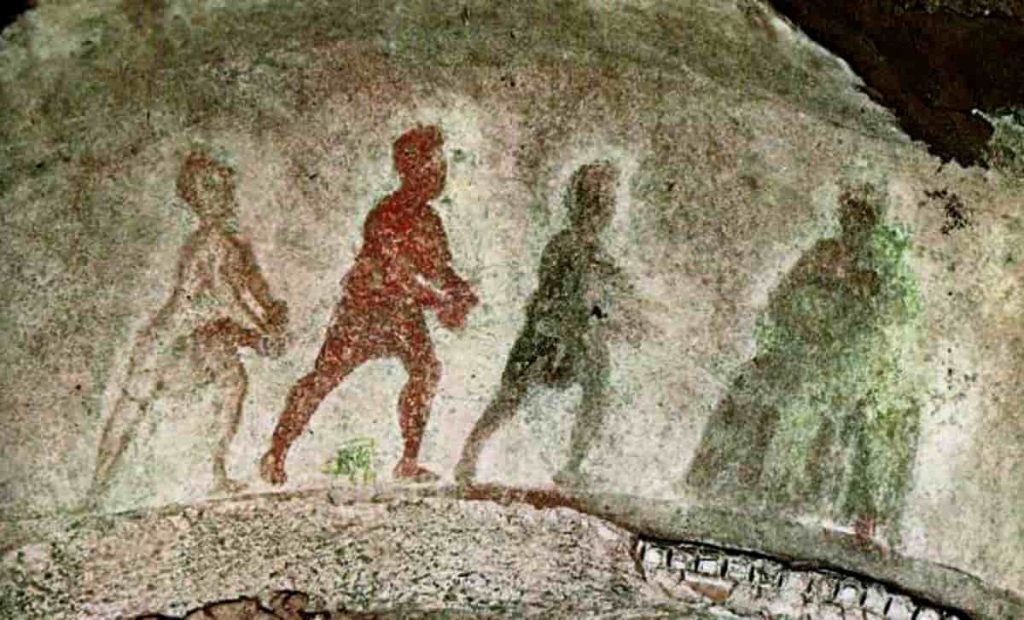

In the area of the catacombs of Priscilla, known as the “Greek Chapel”, in the upper part of a cubiculum made to house sarcophagi, this interesting representation can be found, dating from between 200 and 250.

The fresco is really very simple, but at the same time detailed enough to offer, also in this case, a good indication as to the passage of the scriptures from which the artist of the Magi was inspired.

Arrival of the magi

The scene of the arrival of the ‘magoi’ does not present the usual elements we have come to expect. The three wise men arrive on foot, each subject depicted with disarming simplicity, still retaining its own precise identity, which is also represented through a differentiation in the colour of their clothes.

The distance between the Magi and the Virgin and Child is minimal, a clear sign that the journey of the wise has now come to an end. The three can approach, with a path that proceeds from left to right, to deliver their gifts to the king they have been looking for from so far away.

The star that guided them on their journey, which nowadays is almost completely faded, is depicted right above the newborn and his mother.

The simplicity of the scene does not correspond to the artist’s lack of knowledge of the characteristic and characterising elements of the event as is recounted in the Gospel of Matthew.

The detail of their eastern provenance, for instance, is rendered through the introduction of a particular headdress, typical of the oriental tradition, namely, the Phrygian headdresses that the three are wearing.

This element, just like in the case of the identity of the prophet, does not distract attention from the overall reading of the scene.

The Universal Message of the Frescoes

The understanding of both frescoes is immediate, there is no question of not having grasped what has been seen, because the message that was conveyed is roughly universal.

It is obvious that the reading was reserved for fellow believers, but the symbolism of the elements is not cryptic, it is simply an accessory to what is the purpose of art.

Regardless of the styles or the historical periods in which it is channelled, art has always one primary purpose, that is, to share messages and give emotions.