“Indian” vocational and residential schools have a long history in the US and Canada, with each seeking to achieve the cultural extermination of indigenous peoples. Throughout the existence of these schools, an uncountable amount of sexual, verbal and physical abuse was inflicted upon these essentially kidnapped youth.

The Uncovering of Mass Graves in Canada and the United States

In May 2021, 215 bodies of children were found buried on Kamloops Indian Residential School grounds in Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada. Following the incident, the US Interior Department began their investigation of US schools and uncovered over nine graves of indigenous children at the Carlisle Indian Industrial school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, United States. What followed since has brought forth to the colonist public’s attention the systemic destruction of indigenous communities, cultures, and peoples.

All of this is something that Indigenous Nations have known since the schools` beginning in the 17th century. As it currently stands, about 1,308 unmarked graves have been discovered in Canada. While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates that there are many more amongst the 140 former Canadian residential schools. In the US, the Department of Interior has identified 53 burial sites and expects this number to grow with further investigations of the recognised 408 US boarding schools. These traumas and broken families, coupled with inadequate education, have left indigenous peoples at a systemically intergenerational breaking point.

Residential School Timeline (USA)

Efforts to eradicate indigenous culture in the US began early, with denominations of Catholicism and Protestantism creating missions focused on indigenous education starting in the 1600s. These missions, crafted to convert indigenous people into the Christian faith, burdened their students with unfair education and disproportionate labour. In time, the federal government would take control over these boarding schools beginning in the late 19th century. The following timeline reveals significant events and projects that contributed to the cultural genocide of indigenous peoples:

1631: Several missions began developing in the 1600s with the aim to convert indigenous peoples into the Christian faith and colonist society. One mission in Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts, was established by Puritan missionary John Elliot who used the mission to reach indigenous communities and encourage them to take on colonist ways of dress and lifestyle.

1655: From 1655 to 1697, Harvard University would run its own Indian College in Massachusetts. Harvard’s Indian College was also used for assimilation efforts into colonist culture and religion. In fact, John Elliot used the college and its students to assist him in his project of printing the first Bible in the New World. This written work would be known as the “Eliot Indian Bible” and was written in the Algonquian language (Natick dialect).

1754: Another mission was an antecedent of Dartmouth University, a renowned Ivy League institution, known as Moor’s Indian Charity School. Moor’s School was established in 1754 by Eleazar Wheelock in Connecticut (eventually moved in 1769 to New Hampshire), where the unenrollment of indigenous students increased due to excessive labour and corporal punishment.

1801: According to the US Department of Interior, the first Federal Indian Boarding school was established in 1801 in the United States.

1819: With the Indian Civilization Act Fund enacted on March 3, 1819, the federal government supported many Christian denominations to continue their efforts of indigenous cultural genocide in the United States. For $10,000+ a year, the government expected missions and institutions to introduce the “arts of civilization” to indigenous communities. The repeal of this act would take place in 1873.

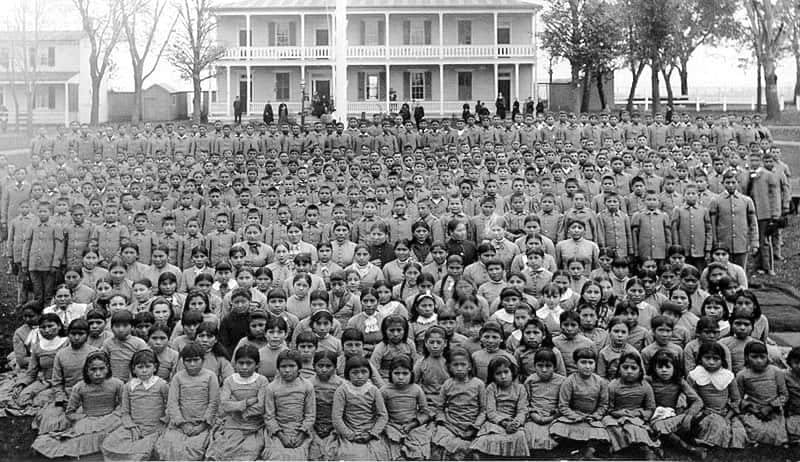

1879: A new system developed with the establishment of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1879-1918) in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It was marked by its significance as the first federal off-reservation residential boarding school and further influenced the systems in Canada and Latin America with its philosophy of complete assimilation through cultural genocide and strict military discipline.

Like the missions before, the Carlisle school stripped its students of their indigenous culture by implementing strict rules stating that each student was to take up a colonist name, clothing, the English language, the puritan religion and cut their hair. Maintaining ties to their culture was strictly prohibited, and students would face corporal punishment for breaking these rules. In some cases, older students were forced to physically punish younger students. The following statement is told by Sun Elk from the Taos Pueblo on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School:

“They told us that Indian ways were bad…we wore white man’s clothes and ate white man’s food and went to white man’s churches and spoke white man’s talk.”

With assimilation being a focal point, Pratt heavily limited all visits and the returning of Carlisle’s students to their families. To further minimise community contact, Pratt developed an “outing” program. In this program, rather than sending students home, Pratt placed students with white families for the summer and during the school day, where they would serve as maids and farm labourers. Furthermore, students would make earnings, although many received little, if any, of their wages and white families heavily took advantage of these children.

Under the care of Pratt and other Carlisle staff, students experienced poor living conditions rooted in discrimination. These indigenous children were not just overworked and ill-fed but had been abused mentally, physically, and sexually during their enrollment. In many worse cases, students died under these horrible conditions, and others never returned home at the end of their time at Carlisle. While Pratt envisioned that indigenous communities would successfully conform to colonist mainstream ways, his efforts left his students as strangers to both their indigenous communities and colonist society.

1890s-1900s: Mission schools began to decline and schools directly controlled by the federal US government grew into the 1900s.

1893: (March 3) Congress would order the withholding of rations to Indigenous Nations and families who refused to send their children to boarding schools. Following this time, the federal government would kidnap and remove children from their reservations and send them to off-reservation schools without parental consent.

1898: Official document Rules for Indian Schools Service issued 1898, which consisted of the requirement that all instruction and conversation within the institutions were to be conducted only in English. A total of 262 rules are stated within the book to share how non-reservation, reservation, and day boarding schools shall operate in order to successfully assimilate indigenous children.

1918: The Carlisle Indian School eventually closed down in 1918, but its harsh philosophy continued to grow in more than 24 US federal off-reservation schools modeled after it.

1928: Beginning in the 1920s, many schools saw a decrease in federal funding and rations of food and clothes were significantly cut. A Meriam Report titled “The Problem of the Indian Administration” was published in 1928 and detailed the poor conditions of residential boarding schools in terms of health, sanitation, finances, and poor staffing.

1930-1960: Indigenous students attending public [State] schools in the US began to increase in the 20th century, with about 900 students attending public schools in 1909 to nearly 48,000 attending public schools in 1932. The number of indigenous children attending public schools continued to grow into the following decades, and unenrollment from boarding schools increased as well.

1960-1969: Boarding schools began to shut down across the nation with the inhumane treatment of indigenous children catching public attention and condemnation by several activists. In 1969, the indigenous education program was reformed and developed over time into the modern education programs run by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) today.

Present: Currently, the US lacks the proper programs to collect the experiences and stories of the indigenous peoples who went to these residential schools. Due to this, the US Department of Interior has declared a mission to investigate and address the harm in these schools, and revitalise the indigenous culture and language through the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative beginning back in June 2021.

Residential School Timeline (Canada)

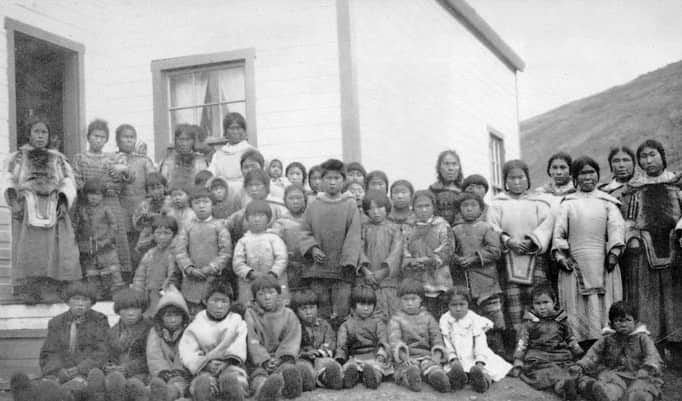

Like the United States, residential schools were established as an arm of the colonial institution and began in the 1600s. Initially, these schools, which forcibly removed children from their homes, were administered by the various Protestant denominations and Catholic churches through their missionaries. In Canada, federal involvement in the operation commenced in the 1840s.

1830: Jurisdiction of Indigenous Affairs for applicability to law and regulation was transferred from the military to the governors of Upper Canada (British) and Lower Canada (French). The policy change signified a shift in external relations with First Nations, Inuit and Métis to assimilation into Canadian society and territory.

A couple of the reasons this came to be is the aftermath of the War of 1812 between Upper/Lower Canada and the indigenous Confederacy against the United States. The Confederacy disbanded in 1813. Despite being instrumental in the war’s victory, indigenous peoples were thereafter seen as an inconvenience to the colonial government. Since no Confederacy or tribes were recognized (at least in practice, since the Royal Proclamation of 1763’s wampum belt exchange had differing cultural interpretations) under the colonial establishment’s Treaty of Westphalia, Britain could incrementally take indigenous territory. Hence why the transition from international to domestic jurisdiction in 1830 facilitated this shift.

1841: After being a professor at Oxford, Herman Merivale, one of the foremost scholars of his time pertaining to the “Native Question,” gained the permanent position of Under-Secretary of State for the Canadian Colonies. He sought to “civilize” the American “Indian.”

The most notable work of his career was the creation of four policy solutions to the aforementioned “Native Question”: 1. Extermination (by death or enfranchisement), 2. Slavery, 3. Insulation (reserves) 4. Assimilation.

1842-1844: The Governor General’s Commission Report officially proposed residential schools with the forced separation of the child from their family, and mandated the proliferation of Indian Status. (Note, this was the highest position in the executive branch of government in Canada – even above the Prime Minister – and served as the mouthpiece to the monarch.)

It should be noted that to this day, Indian Status remains in effect. Status made peoples in Canada hold only one legal category, either Indian or Citizen, each with its own swath of repercussions. Indian Status comes with its own rights and benefits, such as certain tax exemptions and sustenance hunting unburdened by tagging efforts of conservation authorities.

1846: The Indian Affairs Superintendent at the General Council of Indian Chiefs and Principle Men said, “It is because you do not feel, or know the value of education; you would not give up your idle roving habits, to enable your children to receive instruction. Therefore you remain poor, ignorant and miserable. It is found you cannot govern yourselves. And if left to be guided by your own judgement, you will never be better off that you are at the present; and your children will ever remain in ignorance. It has therefore been determined, that your children shall be sent to Schools, where they will forget their Indian habits and be instructed in all the necessary arts of civilized life, and become one with your white brethren.”

1857: The Gradual Civilization Act was enacted. The Act forced any “Indian” man over 21 to lose their Indian Status if they (a) could speak, read and write either English or French, (b) were of good moral character, and (c) were free from debt.

1879: The Nicholas Flood Davin report stated, “Indian culture is a contradiction in terms…they are uncivilized…the aim of education is to destroy the Indian.”

1885: Traditional “Indian” ceremonies are declared illegal in Canada.

1892: The Canadian Government and Christian Churches enter a formal agreement for religious organizations to operate the schools. The pupils would be Status and non-Status Indians, Métis and Inuit children. The children were referred to as “inmates.”

1892-1948: Under the threat of possible prosecution and fines, the Canadian Government coerced parents into sending their children to residential schools. Parents were forced to sign custody over to the school’s superintendent/principal.

Priests, “Indian agents,” and police officers kidnapped children from their homes and communities. The authorities then transported these children to residential schools large distances away to discourage potential escapes.

1928/1933: The provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, respectively, legalized the sterilization of any “inmate” of residential schools. It frequently occurred to whole groups of indigenous children as they hit puberty.

1945: It was illegal until now for “Indians” to attend public schools

1948: The mandatory attendance of residential schools is put to an end, but the schools remain in operation.

1960-1980: Commonly referred to as the 60s scoop, children were kidnapped without their communities’ and families’ knowledge. Government officials and social workers did this based on cultural inferiority and that indigenous peoples could not adequately provide for children. Once the Children’s Aid Society had abducted the children, they were placed in the foster care system or up for adoption to non-indigenous homes. A predominant number of adoptions were to locations outside the originating province, with many also being sent to Europe.

1996: The final Canadian Federal Indian Residential School shuts its doors and is soon after demolished.

The Intergenerational Trauma of Indigenous Nations

Intergenerational trauma affects not simply individuals but their entire communities. Through colonialism and cultural assimilationist practises, components integral to indigenous cultural identities have been lost to time. Such a disconnect between an indigenous person and their cultural heritage proves to be an additional obstacle to overcome. The following sections unravel statistics of prevalent issues among the indigenous Nations exacerbated by the abusive conditions within residential schools in the Americas:

Suicide Rates

Such a disproportionate amount of barriers are present amongst indigenous Nations that suicide is the second leading cause of death for indigenous youth from 15 to 24 years old. Statistics reveal that an estimated 37.2% of indigenous adults with a parent who attended a residential school had thoughts of committing suicide.

These percentages of suicide can, in part, be attributed to the trauma endured by indigenous students in residential boarding schools who experienced malnutrition, corporal punishment, overcrowding, and overall neglectful conditions. The traumas experienced, especially during childhood formative years, play a significant role in lifelong behaviours. Thus, the kidnapping, abuse, and deaths beholdened by a majority of the indigenous population have significantly impacted residential school survivors and their descendants.

Substance Abuse

The experiences indigenous children have undergone during the residential boarding school era have also contributed to high statistics of substance abuse within the indigenous community:

“Drug use was by and large the most prevalently perceived health problem regardless of location, with only Northern Inuit populations not ranking this as so. That is, overall, 58% of [indigenous] respondents noted this to be the most important health problem.”

The systemic abuse within the residential schools and missions stemming back to the 17th century, while not solely the root of the matter, is significantly responsible for the harm inflicted on Indigenous Nations over time. In a 2014 report, elders reported that high rates of alcoholism could be traced back to patterns of traumatic historical events and repetitive discrimination against indigenous peoples. Hence, the Indian Residential Boarding school era serves as a reminder of historical loss and a duration of inhumane treatment, which has unfortunately led to further struggles for Indigenous Nations.

Crime Rate

Individuals are not born criminal in nature, but are formed through experiences and adversity. Crime can be seen as a means to an end by entire communities who do not have alternative methods of attaining desired outcomes like proper nutrition. From many different introductory points, crime becomes ingrained in the ways of life of many disenfranchised groups and can be intergenerational in nature. This phenomena is evident in that, according to Statistics Canada, 63% of indigenous women have experienced physical or sexual violence in their lifetime compared with 45% of non-indigenous women.

With historical trauma and loss rooted in discrimination, Indigenous Nations and peoples impacted by the experiences of the Indian Residential Boarding school system have dealt with concerning disparities. The lack of governmental action to ensure the physical and mental well-being of indigenous peoples has unfortunately led to struggles with alcohol, poverty, health-care, and mental health among other concerns.

How are Canada and the United States Reconciling?

United States

US Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, issued a Federal Boarding School Initiative on June 22, 2021, following the discovery of 215 mass residential schools graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in May 2021. The investigations seek to identify all US boarding school sites, the names and tribal identities of students, burial sites of indigenous children, and share the impacts and experiences encountered in US boarding schools through the perspectives of students’ descendants.

The first volume of the 102-page report was delivered to Secretary Deb Haaland in April 2022, stating that from 1819-1969, investigations discovered that 408 boarding schools operated across 37 states, “including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii,” where at least 53 burial sites were uncovered.

Moving forward, the report suggests conducting a volume II of the investigation, where it seeks to gather more historical data pertaining to Federal Indian Boarding schools and its attendees, fund efforts to revitalise indigenous languages across schools, promote indigenous health research, and create a Federal memorial to “recognise the generations of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children that experienced the Federal Indian Boarding school system”.

In May 2022, the DOI Secretary supported the volume II recommendations by launching “The Road to Healing” tour that would seek to share and record the stories of Indian Residential Boarding school students and their descendants across the nation. With the funds of 7 million dollars, Volume II will continue its work through 2022 into 2023 to unravel the burial sites of indigenous children, address key impacts of the Federal Indian Residential schools on indigenous peoples from the United States, and revitalise indigenous culture and language.

Canada

The foundation of Canada has shifted after the discovery of the unmarked graves in 2021. Regular folk continually have open conversations across the country about the genocide on these lands. However, the discourse among the general Canadian populace about reconciliation is being facilitated by mainstream media, which, over a year and a half after the discovery, still covers First Nations-centric and reconciliation topics. Some individuals can be found flying the orange All Children Matter flags associated with the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation all the year-round. The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was established in the wake of the unmarked grave discoveries. The ability for people to plead ignorance on the inhumanity perpetuated systemically has considerably receded. This reduction is from the widespread acknowledgement of events, regardless of political stripes.

Although the discoveries only further affirm the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2007-2015, the culmination of these events inspires a new society. There is a long way to go before reconciliation can, if ever, be reached, but it is necessary for the livelihoods of each Canadian that this route is traversed.

The Government of Canada has supported the availability of ground penetrating radar for First Nations communities to use if they so desire. For example, the Trudeau Government provided $1.44 million to conduct these preliminary investigations to Williams Lake First Nation. Fiscal support for indigenous communities has amounted to almost half a million Canadian dollars in total.

Aside from the financial support provided to address the residential schools, the Government of Canada has been far more provisional for long-term investments benefitting indigenous communities and peoples. The Government has also expedited its response because of public pressure to address the boil water advisories affecting solely First Nations. Many of these advisories have been in place for decades and signify the lack of clean drinking water available to a substantial demographic of the Canadian population. Since the Trudeau government was first formed in 2015, 135 long-term water advisories have been lifted, but 31 are still in effect in 27 communities.

Despite the present acknowledgement of the adversity that Indigenous Nations have faced, fiscal support, and cultural recognition of this horrendous history, are the only way to ensure that needs are met. Moreover, these results have to be delivered consistently. A short-term attempt at making amends with indigenous communities is the worst response to these events that Canada and the United States could possibly make, since these are existential threats, not passive ones.

- The following article was written on the uncoded territories of the Algonquin and Gabrielino-Tongva peoples. It was written from the perspective of the colonist public; no views within this piece necessarily reflect indigenous peoples nor First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities.

- This article covers sensitive topics about the Indigenous Nations and peoples in Canada and the United States. If at any time you are experiencing distress over this topic and you are an indigenous person in the US or Canada please call 1-866-925-4419.