The EU is a remarkable institution, but its callous exclusivity has risked making it a gentlemen’s club, whose head is very much up its own backside.

Many criticisms have been levied at the EU, a fair amount, as we shall see, may be justified, but most are part of that process that developing organisations with such a mighty mandate have to go through. All said and done, the benefits far outweigh the drawbacks, as Britain’s ever-increasing list of post-Brexit crises, on the one hand, and the eagerness of neighbouring nations to join, on the other, makes evidently clear. There is, however, one flaw that unless remedied as a priority, will risk making the Union a gentlemen’s club, whose head is very much up its own backside. Rude language, but the reality is far ruder. I am referring to the EU’s callous exclusivity, which I will refer to as its Golden Curtain.

The remarkable achievements of the EU

The vision that led to what is now the European Union was fuelled by a desire for peace and mutual security. It was never meant to emerge as a sudden transformation, from countries that were at each other’s throats to a jolly fraternity holding hands in a garden of earthly delights. As Robert Schuman, one of the main pioneers of the Union, said:

“Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity.”

Strengthening financial interdependence was one of the motivators of this solidarity, which explains why the European Economic Community (EEC), created by the Treaty of Rome in 1957, was one of the first milestones of the Union. It has gone a long way since then. Everything is easier now for EU member states: inter-community trade, travel, study, migration, shopping…

Even EU countries that have not adopted the euro are happy to be paid in euros. Everything is so easy and so easy to take for granted too, as many British people are beginning to find out. Of course, for people who sit in front of the television from dawn until dusk, these kinds of benefits mean little. The Union has moreover consolidated that solidarity that will make a war between EU nations almost impossible. Finally, to the chagrin of the Trumps and Putins of this world, it has created a powerful quasi-federation that can hold its own against other superpowers. What’s there not to like?

The darker side of the EU

As mentioned above, the EU has its fair share of faults. Some of these faults concern the governance of the institution, such as corruption and lack of transparency. In October 2012, for instance, there was a scandal involving the EU commissioner for health, John Dalli, who had to resign after an anti-fraud inquiry linked him to an attempt to influence tobacco legislation in favour of a fellow Maltese contact. The EU bureaucracy is also criticised for putting the needs of the private sector before those of its citizens.

Other weaknesses are linked to its structure which lacks a common language and a cohesive fiscal policy, leading to misunderstanding in the first instance and imbalanced financial dependability in the second.

One of the main problems of the EU, which impacts justice head on, is its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which was launched 60 years ago. Its main aim is to support farmers and affordable productivity in a sustainable and environmentally friendly way. These are noble causes, but as the saying goes, the path to hell is paved with good intentions. The agricultural policies have done more harm than good. They have encouraged overproduction and helped the meat and dairy industries become one of the main contributors to climate change. They have also penalised developing countries thanks to local subsidies that have made it difficult for them to compete, both within the EU and within their own borders as heavily subsidised imported goods can be cheaper than homegrown ones.

This said, the EU remains the world’s biggest importer of agricultural goods from developing countries and it is attempting to address the problem through such schemes as the 2001 Everything but Arms (EBA) programme, which removes tariffs and quotas from the least developed countries. The EU has also addressed other issues by creating the new CAP (A Greener and Fairer CAP), which was formally adopted on 2 December 2021 and is due to be implemented from 1 January 2023. The issues addressed here, however, are more localised, such as fairer payments of subsidies to smaller farms, a more equitable distribution of funds to member states, more stringent labour rights and a focus on gender equality. Also, sadly, animal rights don’t even get a look in, while the devastating effects of intensive farming are virtually passed over.

This is just a cursory view of the EU’s weaknesses and is by no means exhaustive, as my focus in this article aims to be that Golden Curtain mentioned in my introduction.

The Golden Curtain

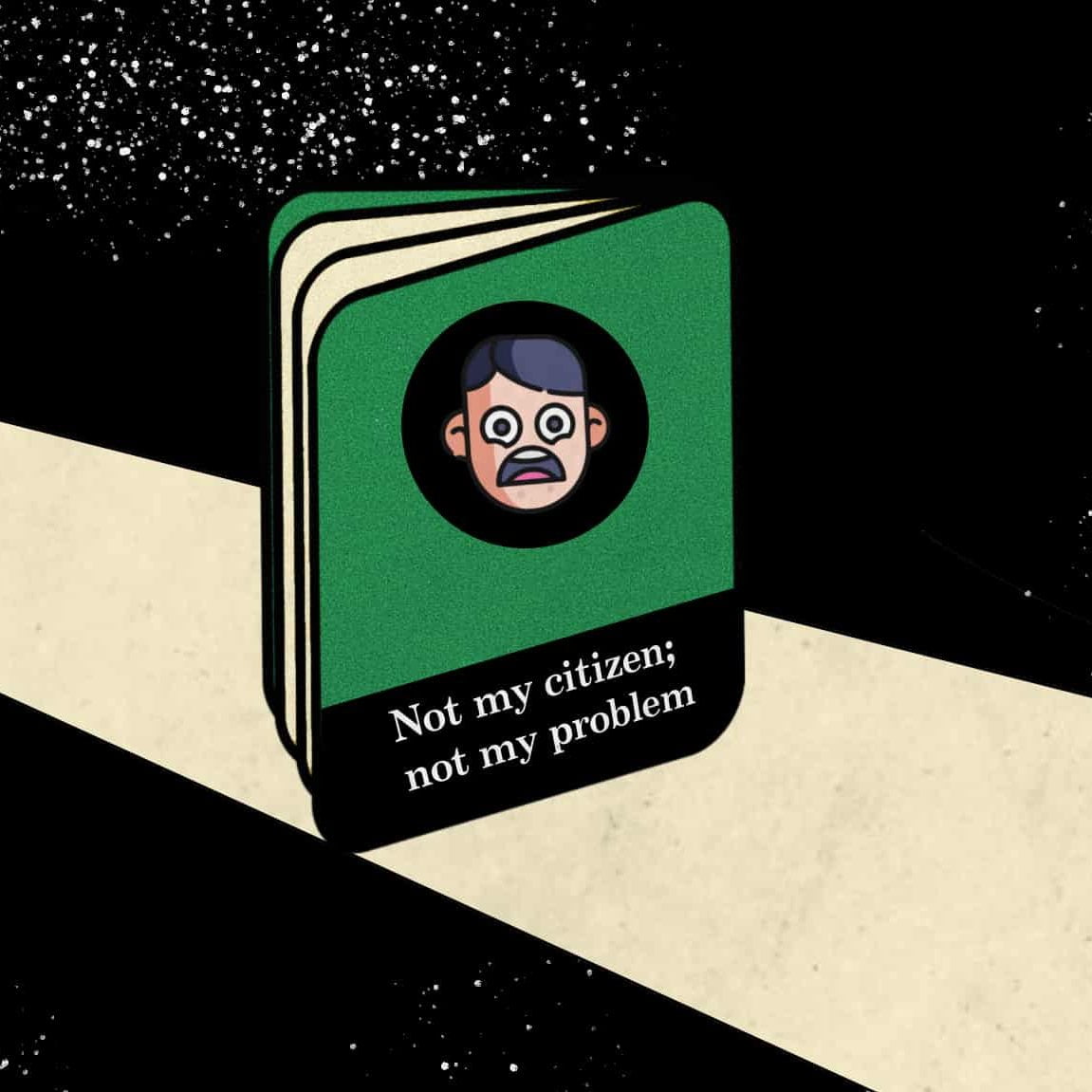

In some ways, the EU is like the Soviet Union. The latter erected the dull Iron Curtain: a political barrier supported by its military might, to seal itself off from Western interference and ideologies, while keeping its citizens firmly in. The EU has erected a glamorous Golden Curtain: a comfort zone, supported by its military might, to seal itself off from foreign interference and ideologies, while keeping other’s citizens firmly out. In this context, we can speak of three categories. The first consists of nation states wishing to join the Union; the second is made up of asylum seekers and migrants who are seeking refuge or a living in an EU member state; while the last involves individuals who simply want to visit one or more EU countries.

EU membership

At an EU summit in Brussels on 23 June 2022, Ukraine and Moldova were granted EU candidate status. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its aggressive posturing added a touch of urgency to these applications. Georgia’s candidacy, however, was deferred owing to outstanding issues, while no progress was made regarding the application of the Western Balkan states, some of which are still going through turbulent times. Joining the club is not easy and even the privileged candidate states may have to wait a long time before their membership process is completed. This is fair enough.

A rogue member could undermine the institution from within, so caution and prudence are quite justified. One need only observe how Turkey’s President Erdogan is behaving in NATO, to understand that certain guarantees are preferable when admitting a member who will then wield substantial power within the organisation. Nevertheless, all the guarantees under the sun cannot safeguard against political erosion within a country. Hungary, for instance, is leaning further and further to the right and it may only be a matter of time before its position in the EU will be untenable. Still, at least the EU is doing its best here. Sadly, this cannot be said with regards to the next two categories.

The EU on asylum seekers and refugees

Whilst the EU’s focus should be on how to assist as many migrants as possible in a dignified and humane way, its obsession seems to be on how to keep them out. The budget for the EU’s migration and border management has rocketed. Frontex, the EU border and Coast Guard Agency has been increased by 194%, while overall funding for law enforcement, border control, military research & development and operations has increased to a whopping €43.9 billion, which is over 30 times higher than funding allocated to rights, values and justice. These funds also cover the strengthening of third country operatives to deal with migrants and refugees and stop them in their tracks. A recent guide, co-published by Statewatch and the Transnational Institute called: At what cost? Funding the EU’s security, defence, and border policies, 2021–2027 paints a grim picture of the tightening of borders that were already unwelcoming to start with. In its conclusion it states:

“The funds will significantly strengthen the internal and external security machinery of the EU and its member states, reinforcing both their repressive and aggressive powers. Police databases and information networks; intrusive counter-radicalisation policies; border surveillance technologies; detention centres; migration “hotspots” such as those already-established in Greece and Italy; weapons research; the development of security and military technologies; and an increased number of military operations will all receive increased financial backing through these budgets. These goals are being cynically pursued with comparatively little additional funding for human rights organisations and activism...”

Meanwhile, images of refugees being beaten by Greek border guards or left to freeze to death by Polish ones are recent enough, as is the repeated story of Malta ignoring distress calls from migrants at sea. People are dying, people are being abused. Does the EU really believe these people are worth less? Or is it too frightened of voters in national states to do the right thing?

The situation is not much better for those who make it in. They are confined to their point or country of entry and kept in limbo for months awaiting judgement. If they manage to reach another EU country, according to the Dublin 3 Regulation, if found, they are soon returned to the original EU one. Moreover, the situation is complicated by there not being an EU level agreement on quotas for hosting asylum seekers. Individual states are touchy about the subject as a welcoming stance can spell disaster at the polls. This should make it all the more imperative for the EU to take control. Even though the EU can also be vulnerable to hostile voters, as a block it is in a better position to pursue inclusive policies and to educate the xenophobic elements of the public that human rights are not just national rights.

The Golden Curtain is just as rigid as the Iron one.

Rejection rates for those waiting at camps to see whether they have been granted asylum can also be very high. In 2021, for instance, the rejection rate for asylum seekers in Italy was 56%, with the highest rates for people from Tunisia (92%), Bangladesh (85%) and Egypt (84%) and the lowest rejection rates for people from Afghanistan (3%), Somalia (4%) and Venezuela (6%). The full picture is along those lines and can be viewed on the Asylum Information Database.

Of course, If you just want to move to an EU country for cultural, economic or other reasons, you clearly do not stand a chance unless you are ridiculously rich or meet other genteel requirements. Working visas can be more flexible, but only if your particular skill is in demand. So all said and done, the Golden Curtain is just as rigid as the Iron one.

Visiting the EU

According to a European Parliament Fact Sheet:

“In 2018, the ‘travel and tourism’ sector directly contributed 3.9% to EU GDP and accounted for 5.1% of the total labour force (which equates to some 11.9 million jobs). When its close links with other economic sectors are taken into account, the tourism sector’s figures increase significantly (10.3% of GDP and 11.7% of total employment, which equates to 27.3 million workers).”

With such high numbers, one would think that visiting an EU country was easy. Well, yes, if you are affluent or from an affluent country, but if not, you are more likely to hit your head on the Golden Curtain than land your feet on a red carpet. The statistics are bleak and can be found on the Schengen Visa Website.

The average rejection rate for the issuing of a Schengen visa for all states in 2021 was 13.4% with Sweden, Norway, France and Denmark being most likely to turn down a request. This percentage may not seem that high, but it is averaged out by “westernised” applicants from countries like Australia, Canada and Japan. It is also worth noting however that visa applications at a particular consulate, will not necessarily be submitted by nationals of that country.

Sticking with Italy as an example, in the case of its consulate in Ghana, 57.92% of applications were rejected. We are not talking about immigration here, just holidays, business trips or the like. Rejections from consulates in India, Morocco and Nigeria were also high, but it is interesting to note the difference between respective consulates:

India

- New Delhi: 45.80% rejection rate

- Kolkata: 22.21% rejection rate

- Mumbai: 14.59% rejection rate

Morocco

- Casablanca: 41.63% rejection rate

- Rabat: 12.28% rejection rate

Nigeria

- Lagos: 30.88 rejection rate

- Abuja 1.86% rejection rate

You would be justified in thinking that the huge discrepancy between consulates in the same country reflects the demographics of the area. However, this is not necessarily the case. There is so much subjectivity in the process and so little in the way of clearcut guidelines, that some consulates are known to be stricter than others (more racist?).

People are often aware of this and learn which consulates to avoid. Official reasons for rejections range from incomplete or not fully legible forms to lacking evidence regarding the suitable funds for the journey or having a criminal record. Whilst many rejections may be valid, many rejections are arbitrary and a blatant abuse of human rights.

When I lived in China, I was horrified at the amount of decent hardworking people I knew who were turned down for visas to Europe. The discrepancy between consulates in the same city is telling. Whilst the Italian Consulate in Guangzhou turned down 21.58% of applicants, Germany’s consulate in the same city only turned down 2.96% and France’s 2.53%.

Every case involving rejection is blow to the hopes, aspirations and prospects of the applicant. Perhaps they wanted to see the Pope or the Leaning Tower of Pisa; visit a friend or a relative; find out about business opportunities… Every case is a story.

The story I would like to briefly recount here involved my dear friend and colleague Ariana Yekrangi, co-founder of UN-aligned. A few years ago, his younger brother died tragically in China. His mother went to China from Iran to sort out the funeral arrangements and offer comfort to her other son, the twin of the deceased. She then tried to go and visit Ariana, who was living in Finland and was only 24 years old at the time. Despite the fact that she travels widely (as photo galleries in The Gordian testifies to this), her application was turned down.

Respect for private and family life are enshrined in Article 7 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, and yet for no apparent reason, her application was turned down. Political reasons prevent Ariana from visiting his mother in Iran, so they will have to meet in a third, non-EU country because some EU bureaucrat thinks it wise to keep the family apart. There are thousands of Ariana’s, with stories that are equally or even more absurd and moving.

The Golden Curtain is turning the EU into a fortress, a type of Noah’s Arc that cares little of nothing for the lives of others. If this is its idea of justice, it had better think again.