Petronilla Paolini: Her tragic life and daring poems

Born in 1663, Petronilla Paolini broke through society's patriarchal cage with the only weapon she had at her disposal, her art... writes Carla Pietrobattista.

Up to now, I have mostly shared my impressions on art intended as visual art, examining paintings or sculptures. I have rarely strayed into technical intricacies when writing about art because when I decide to talk about a topic, I do not follow particular selective criteria, I simply rely on my instinct, on the urgency to share emotions and these are almost always solicited by the great works of art history. This time I felt the same solicitations and emotions that I have just mentioned, and I discovered them in part thanks to a casual “encounter”.

A few weeks ago I was asked to write a short introduction to a book that will soon be published: a text that is a reworking, or rather a sort of “translation” of the diary of a writer from the past: Petronilla Paolini, whose memoirs are about to be made known to the public after a re-adaptation of the language that has been made more current and easy to understand.

Although Paolini’s literary works have always been commended by the literati and praised in the milieu of modern literary criticism, due to a historical process of forgetfulness, few people really know her output in-depth, and even fewer her personal history which will be the subject of my essay.

Petronilla Paolini in Magliano: In my case, Petronilla, or at least her name, has never been far, because the noble Paolini family owned a palace in my town: Magliano dei Marsi in Abruzzo. In the immediate vicinity of this building, which was destroyed by the Marsica earthquake of 1915, a street was named after her in order to keep the connection alive. However, apart from the familiar name, I only really got to know the poet later in life. After reading the intense and personal entries in her diary, I felt the need to share the story of Petronilla characterised by gross injustices but also, despite the historical distance that divides us, by a profound modern relevance.

Who was Petronilla Paolini?

The Piazza of Tagliacozzo. © Zitumassin/CC4.0

Petronilla Paolini was born in Tagliacozzo on Christmas Eve 1663 and died in Rome on March 3, 1726. She was the only and beloved daughter of Baron Francesco Paolini and the noble Silvia Argoli. The poet’s early years were quite peaceful, in her diary she describes herself as a happy, intelligent and curious child, keen to know and discover the world. This initial serenity was soon upset by a violent and unexpected event: the killing of the poet’s father on February 13, 1667, very probably for political reasons.

Early life

Petronilla, who as already mentioned was an only child, found herself inheriting a considerable legacy which was the main reason for all the misfortunes that characterised the young woman’s life. Her relatives, especially her father’s brother, began to show great jealousy towards the young woman and, in a strongly patriarchal society like that of the time, they did everything to manage her assets and forcefully replace her mother.

The mother of the young Petronilla did not know how to face the climate of hostility that had fermented around her after the death of her husband and she, therefore, decided to move with her daughter to the convent of Santo Spirito in Rome in 1667. Here the standard of living of the two changed substantially, not only due to the transfer, but because their roles within society had drastically altered. In fact, according to the mentality of the time, the two had simply become women in need of protection and alas they got it!

However, this was at a decidedly too expensive price for the young Petronilla who, on November 9, 1673, at the age of nine, had to marry the forty-year-old Roman nobleman Francesco Massimi, deputy castellan of Sant’Angelo.

A forced marriage

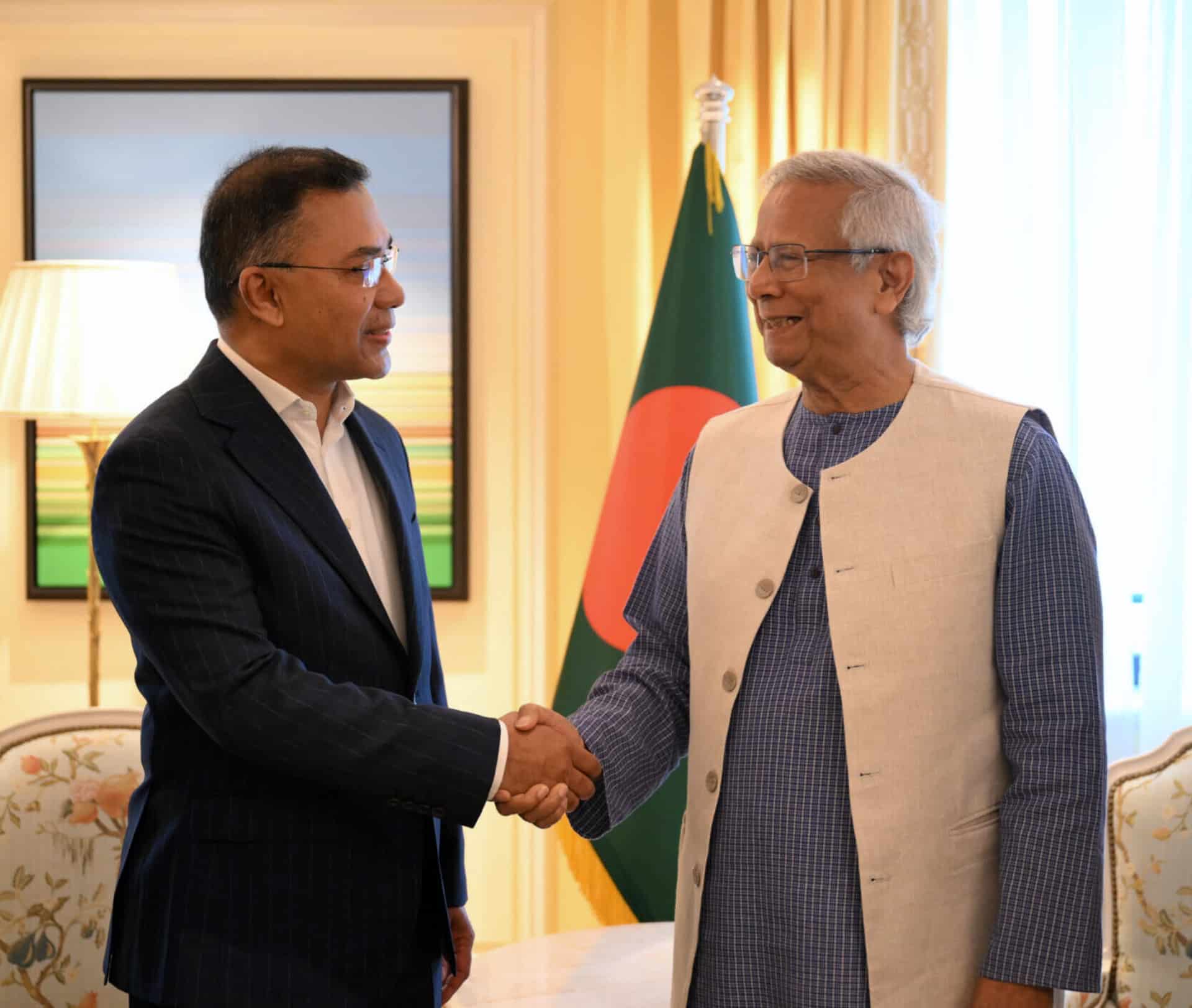

Clement X and his nephew married Marquis Francesco Massimi, who, at the time, was the keeper of the Castel Sant’Angelo.

This was anything but a marriage of love, resulting from the noble feeling of protection. The child bride did not feel love for obvious personal reasons, nor did her husband, who was only driven by economic gain. More than a marriage, I find that in fact, we are talking about a wicked pact masked by respectability and nobility of purpose. A wedding where all the male protagonists of the event skilfully wore a mask, even before the one worn by the “saviour and protector” groom. The most important mask was worn by those who made the celebration of this union possible: Pope Clement X, a relative of the Massimi, who gave a special marriage licence to Francesco.

The strong hand of fate, joined the fair April of my years, to alien old age…

Petronilla moved to Palazzo Massimi in 1675, and then followed her husband to Castel Sant’Angelo in 1678. It is here that the poetess wrote: “Under an illustrious title in closed horror I stepped beyond the most beautiful hours.” The only consolation, the only freedom for the young woman was writing, however, her despotic and jealous husband prevented her from writing and composing poetry.

Petronilla had three sons from Massimi, but becoming a mother did not improve her position at all, on the contrary, the constant harassment and humiliation became so difficult to bear that, on November 16, 1690, she left her husband and children to return to live with her mother at the convent where she grew up.

Resurgence

The vengeful husband, on the strength of a court order in his favour and motivated by the usual feelings of hatred, prevented Petronilla the use of the assets that should have been her due by right, in accordance with paternal inheritance; nor did he allow her to visit or attend to her sick son, Domenico, who later died (1694).

Away from her husband, Petronilla found consolation in her faith, but above all in poetry. Now free to write, the woman began to compose sonnets and other works (see a full list here) that made her known outside the walls of the convent that housed her. In a historical moment in which writing was often the prerogative of men, Petronilla became a member of the “Accademia degli Insensati” of Perugia, of the “Accademia degli Infecondi” and of “Arcadia” in Rome. She was identified by the name of Fidalma Partenide.

In 1707, on the death of her husband, Petronilla left the convent and moved to Palazzo Massimi where she could get back her possessions and, above all, she was able to get close to her children once more. Strengthened by this new freedom, the poet continued to compose and in 1709 she returned to visit the places of her childhood in Abruzzo.

Petronilla Paolini died in Rome on 3 March 1726, and was buried in the Church of St. Egidio. Photo: Rodrigo Soldon/Flickr © CC 2.0

Petronilla died in Rome on March 3, 1726, she was buried in the church of Sant’Egidio in Trastevere where she is commemorated by a small funeral monument.

A women of courage

Reading the official story of this woman, but especially the pages of her diary, I began to see Petronilla with new and different eyes.

I saw in her a woman who lived two distinct lives. In the first, she was a beloved daughter, orphan, child bride, unhappy wife, and mother while, in the second, she was a woman capable of redeeming herself. In this second phase, she was a woman of faith and a mother capable of detaching herself from her children, aware of the fact that time would again allow her the possibility of living her life as a mother. She was not willing to continue being an unhappy prisoner, just to carry out their parenting role.

Nevertheless, it is remarkable how much of Petronilla’s life took place behind closed doors; first those of the convent, then those of Castel Sant ‘Angelo. Yet these cages did not really lock her up; Petronilla broke through them with the only weapon she had at her disposal: her art.

Through her works, she has been able to teach us that no one should be crushed by their own destiny. Everyone can decide to write their own story with the same courage, the same conscious determination of Petronilla, a woman and a poet.