Your guide to T.S Eliot poems - April is the cruellest month

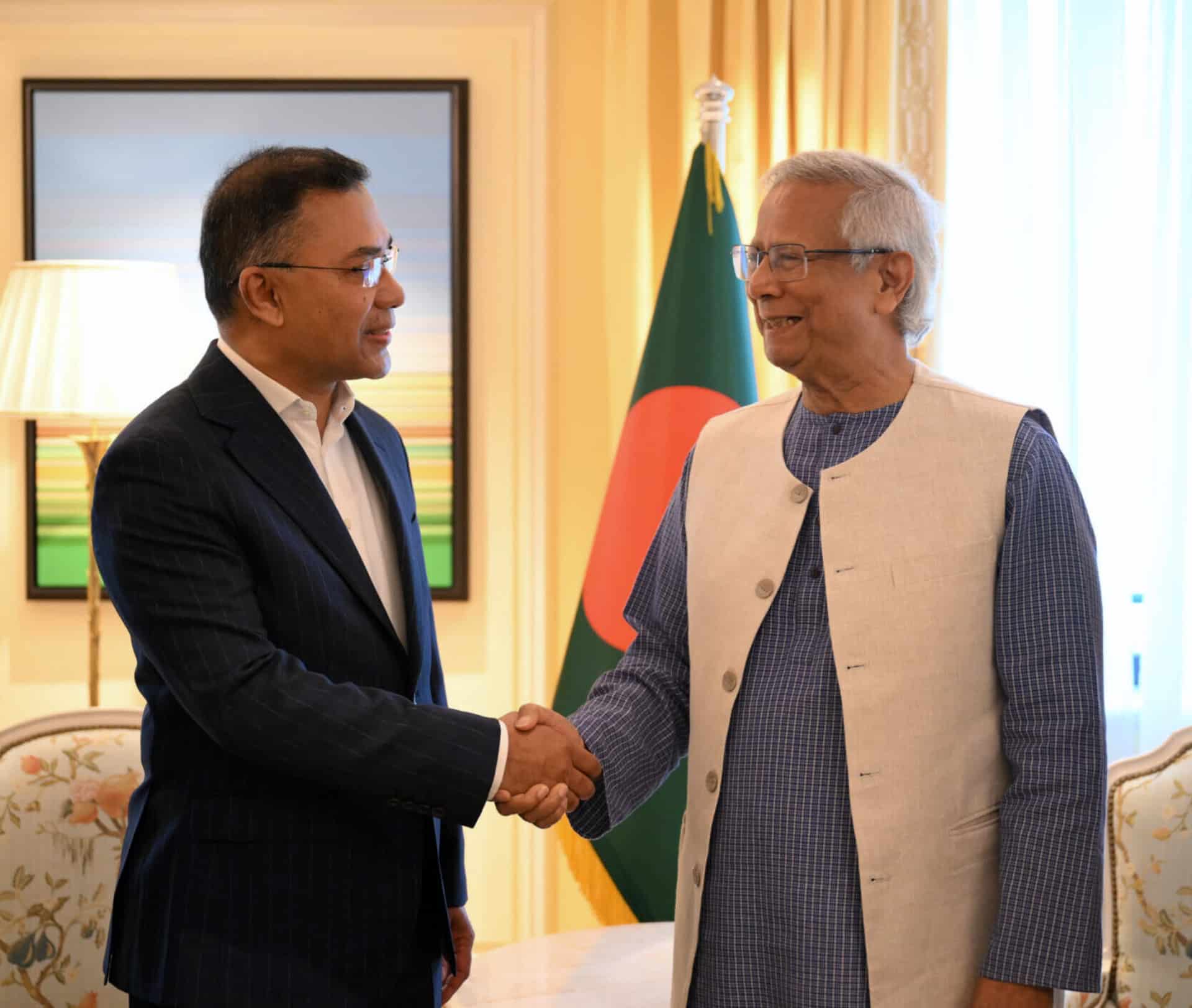

T.S Eliot is perhaps the best example of the modern metaphysical poet. Like the 17th century poet, John Donne, Eliot veered from the ethereal world of romance and idealisation, to head directly towards a concrete reality through conceits and extended metaphors.

His work reflected the upheaval of the social order in the aftermath of World War I, and the failure of all of man’s social, political and philosophical aspirations. On the wake of death and destruction, all seemed to flounder on the crags of a festering humanity that had turned to superficial desires and material gain. Ethical and moral values were reduced to a vast expanse of ash and aridity; a waste land void of any humanity. Humankind had lost its soul.

Portrayals of an arid society

In 1917, Eliot published his first book of Poems, Prufrock and other Observatories and later in 1922, The Waste Land. His reputation as a poet grew quickly and with such great attention came harsh criticism. His poetry blended free verse, rhyme and highly structured poetic compositions. It was a revolution both in style and in content.

Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, portrays an arid society that had become fake and materialistic. The main character, Alfred Prufrock, a middle-aged self-conscious and awkward man, is well aware that his society is flawed and phoney. Despite his insecurity and self-consciousness,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair –(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Prufrock still realises that the people around him are fake and lack the values of humanity. He is the antihero who knows that he should intervene in order to change his diseased society, but is too weak and insecure to do anything about it. He tries to “force the moment to its crisis”, but fails miserably. He avoids the issue and procrastinates:

Do I dareDisturb the universe?In a minute there is timeFor decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

Eliot’s portrayal of Prufrock’s society is a bleak one. There seems to be no hope for redemption, no hope for change. Prufrock’s realisation of the dire dearth within humanity is sterile and feckless. He will continue his own sterile existence with this superior knowledge lodged within him, and he will do nothing about it. He will continue to attend the shallow parties and the women will continue to “come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.”

The Waste Land

The Waste Land reiterates and emphasises this desolate picture of early 20th century society.

It is a narrative poem that deals with the squalid condition of Europe after the First World War. Eliot draws inspiration for this poem from Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, and from the anthropologist Jessie L. Weston’s From Ritual to Romance. The latter, especially, shows the influence of ancient rituals and vegetation myths on Christian literature. Examples of this influence are the legends of the Holy Grail and the Fisher King. The Holy Grail is the cup used by Jesus Christ during his last supper which, according to the legend, was brought to England and then lost. The legendary search for the Holy Grail is an iconic literary symbol for unattainable perfection. The Fisher King, on the other hand, characterises the ruler of a barren country, whose knights search for the Grail in order to restore fertility and rebirth.

The Waste Land depicts these myths within contemporary England.

The poem, in fact, takes on the form of a quest through a desolate land, in search for the possible solutions that could regenerate it. The solutions which this quest provides, however, are only partial. The whole poem is divided into various sections, each investigating different aspects of the spiritual dearth that pervades this barren land.

In this arid landscape, London appears to be a surreal city, where men are spiritually dead and trapped in an endless rut, unaware of their condition. Through references to Dante’s inferno and Baudelaire’s 19th century “swarming city”, Eliot highlights the fact that this condition is emotionless and spiritually putrefied.

In this context, April is the cruellest month, because it is associated with new life. It stands for rebirth, both in the natural world and in the human world. April prompts man to act and to escape from the spiritual barrenness in which he has been condemned. It is cruel because it reveals a rebirth that cannot be. The desolate land of ashes and sterility will prevail. Man has become a robot, callous and emotionless.

The Fire Sermon

A perfect example of this robotic existence, where all values are lost, is The Fire Sermon taken from Section III of The Waste Land. Here Eliot portrays the lack of social, spiritual and emotional values. Even basic communication between lovers is absent. Human beings have become robotic and numb to emotion. Here is a telling extract from this section:

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove and lays out food; in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun's last rays,

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest--

I too awaited the expected guest.

He, the young man carbuncular, arrives,

A small house agent's clerk, with one bold stare,

One of the low on whom assurance sits

As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

Endeavours to engage her in caresses

Which are still unreproved, if undesired.

Flushed and decided, he assaults at one;

Exploring hands rencounter no defence;

His vanity requires no response,

And makes a welcome of indifference.

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

Bestows one final patronising kiss,

And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit...

She turns and looks a moment in the glass,

Hardly aware of her departed lover;

Her brain allows one half-formed thought to pass:

“Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over.”

When lovely woman stoops to folly and

Paces about her room again, alone,

She smoothes her hair with automatic hand,

And puts a record on the gramophone.

In this extract we are introduced to a clerk and a typist who are lovers. Eliot wants to show us how both love and sex have become arid and emotionless. The typist lives in a dreary and untidy little apartment. She prepares a meal for her lover, but it is not a candlelit romantic dinner. On the contrary, she “…lays out food; in tins” within a disheartening backdrop. There is nothing romantic about the setting.

The sexual encounter is representative of a barren relationship in a world where all are dead and dying.

At this point one would imagine that, if the romance is missing, perhaps the sex will make up for it. After all, sex itself can be a positive value if enjoyed reciprocally by the lovers. However, even the sexual encounter is representative of a barren relationship in a world where all are dead and dying. The clerk only wants to perform the physical act of sex and is not concerned with the feelings of the woman he is with. What is worse is the woman’s reaction to his advances. She is completely frigid and unresponsive. His response to her frigidity is also surprising. Rather than being upset or hurt, the clerk “makes a welcome of indifference”. He is content because this means that he can have sex without any effort to interact or to woo his partner. There is no human interaction and both accept this. He could be making love to a mannequin, “His vanity requires no response”, and she is completely oblivious of what is going on. Her zombielike reaction after the act is over, is even more gruelling. All she has to say is, “Well now that’s done: and I’m glad it’s over.”

Both man and woman are here wrapped up in the same aloof monotony, detached from all emotional contact. Her final robotic action of playing a record on the gramophone is symptomatic of the mechanical cycle of modern life, that has been stripped of all humanity.

The ultimate alienation

As Burton Blistein wrote in his Design of The Waste Land:

“Men and women are in [Eliot’s] view hardly more than automata or ‘crawling bugs’ that spawn and die… Just as a record always repeats the same tune, so we encounter repeatedly ‘Birth, and copulation, and death.’ Sustained by craving…”

Blistein points out here that there is no love or sexual intimacy involved in this exchange. We only have primal cravings and urges that are recognised by the most basic forms of life.

The dehumanisation of the modern world is complete.