The Hidden Curse of Babel: The Drawbacks of Language for Communication and Thought

This article highlights the drawbacks of language, not only in its cursed post-Babel scattered metamorphosis, but also in itself, as a means to communication and thought.

The biblical story of the Tower of Babel portrays God rather like the trickster Loki, more intent on mischief, than promoting harmony. Surveying the city and the tower that the descendants of Noah had started to build in order to achieve a level of security and prestige, God says: “If as one people, all sharing a common language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be beyond them. Come, let’s go down and confuse their language so they won’t be able to understand each other." (Genesis 11: 6-7) The final touch was scattering the people all over the world. (Genesis 11:8)

So there you have it: according to this account, our different languages are a curse, as is nationhood. Of course, the likely intention of the author was to justify a fait accompli, rather than to depict God as opposed to universal communication and unity. However, all things considered, languages and nationhood can be a bane; each in so many different ways.

The focus of the story of the Tower of Babel is language, at least it is in the popular imagination, and it will also be my focus in this article. My intention is to highlight the drawbacks of language, not only in its cursed post-Babel scattered metamorphosis (or polymorphosis), but also in itself, as a means to communication and thought.

Language per se

Language gives us wings made of multicoloured feathers, but every feather adds a heavy link to that chain that is the price of those wings. Most of us take language for granted. We use language to communicate and we use language to think: both uses have their pitfalls.

**Language as a means to communication**

When we use language to communicate, we give words an almost divine prerogative. If the word for what it is we wish to express does not exist, we can use other words to describe it. Even if speaking with someone who does not share a common language with us, we still resort to words, though much may be lost in the translation. Body language helps, particularly if we are aiming to relay emotions, but ultimately, words are the gods we worship. This rigidity to the spoken word makes automatons of us all. Sometimes brilliant and outstanding automatons, but automatons, nonetheless. If this were not the case, we would be able to reach out beyond words. Putin’s soldiers would see beyond his branding of innocent people as Nazis. This Big Lie, borrowed from the Nazis with such bitter irony, would be exposed because the words would just not stick.

People who slaughter animals, or happily pay others to do so, would be able to understand what the pig, cow or chicken are saying when they struggle to survive or to save their young or friends, though they cannot use words as such; a fish, even, wriggling and gasping for breath. The butcher shop, with its prized home-grown joints would be a morgue full of murdered corpses deftly mutilated for putrid morsels of carrion. The facts are the same, only the lustre of the words is different.

We literally feed on euphemisms

The same goes for society’s changing taboos which often come with vile and salient words. Yes, we tyrannise with words and let words blind us to what lies beyond. They condition us as powerfully as Pavlov’s bells and like all good things, they are quite dangerous when abused.

Also, if we were not so conditioned, we would see borders for what they really are: lines drawn on dry sand on a windy day. When laws are fair and respected, borders mean little. The EU is proving that, although of course its collective laws are far from perfect. So if we want to benefit from words, whilst being free from their tyranny, we must always be a few steps ahead of them and prioritise the concept, of which they are merely the messengers. After all, occasionally, messengers lie.

Language as a means to thought

In some ways, words are even more insidious when related to thought. This is because, unless we learn how to transcend them, they literally become a programme to which we are entirely bound. Indeed, they do work; just as the survival mechanism within an ant colony works, but evolution or self-development would be very slow, or even impossible in such a context. If we learn to let go of words, even if only occasionally, we will find that we can go much further; a bit like swimming without the armbands that helped keep us afloat. This is one of the reasons why many mystics put so much emphasis on meditation. Releasing ourselves from words opens up new potential. The Tao master, Chuang Tzu expressed this idea beautifully:

“The purpose of a fish trap is to catch fish, and when the fish are caught the trap is forgotten. The purpose of a rabbit snare is to catch rabbits. When the rabbits are caught, the snare is forgotten. The purpose of the word is to convey ideas. When the ideas are grasped, the words are forgotten. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words? He is the one I would like to talk to.”

The curse of different languages

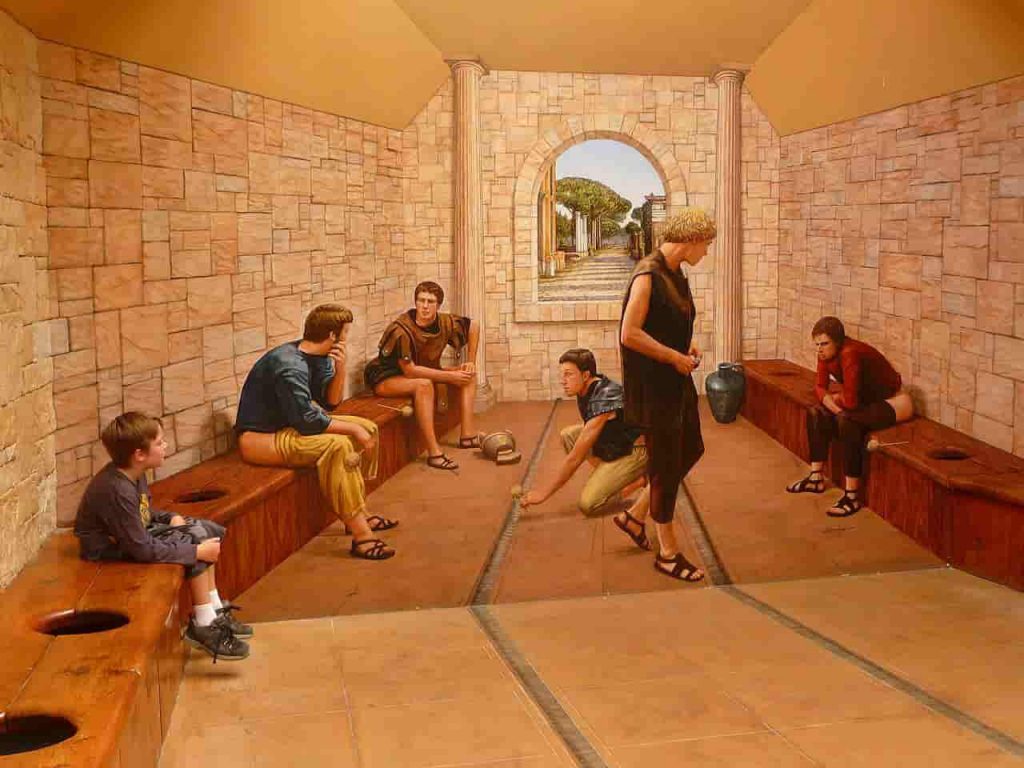

Nowadays, there are over 7,000 languages spoken worldwide. Each one carries its own particular cultural twists. Italian, for instance, has words for pasta that is over cooked (scotta) or food that has not got enough salt (sciapa), highlighting the importance Italians place on culinary delights. However, they do not have a word for ‘privacy’; which is perhaps not that surprising when one thinks of the toilets of ancient Rome.

No privacy in sight: A model of the toilets of ancient Rome. ©Pixabay

All these languages form a rich cultural heritage and we should do all we can to preserve each and every one of them. Sadly, many only have a few speakers left and are rapidly becoming extinct. Every year a few are lost and this year we have already lost one: Yahgan, which was spoken in Chile’s Tierra del Fuego. This said, the downside cannot be overlooked, namely the fact that the lack of a lingua franca for all nations and races results in serious communication problems. UN-aligned proposes to have English as a lingua franca that can be taught as a second or other language all around the world. Whilst English may not be the most widely spoken native language (that privilege goes to Chinese, with Hindi and Spanish high on the list) it is the language with the most speakers overall. Teaching English as a first or other language in all schools around the world would facilitate communication and promote understanding. As the biblical account says, with a common language and a common goal “nothing” people “plan to do will be beyond them”.

Power loves the status quo

The purity of language and its ability to evolve freely is a matter of justice. This is more than just a matter of freedom of speech or about words that relate to our individual human rights, such as labels and pronouns. It is about truth. I am not referring to the blatant lies many politicians love to indulge in, particularly before a general election or an assault on civil liberties. I am talking about an accepted nomenclature that is based on deceit. So let us redefine a few words as an example.

1. Immigrant: Someone who is exercising their right to settle where they please.

2. Meat: Flesh in an early state of decomposition that belonged to an individual who was captive, abused and finally murdered.

3. Religion: A belief, shared by many, which often becomes a tyranny towards those who do not share the same belief.

4. Marriage: A social contract that is bound to the arbitrary laws of the land.

5. War: A convention that allows people to kill each other and anyone who gets in their way, and to cause havoc and destruction. A war crime is something that further legitimises the above by identifying only certain extreme atrocities as unlawful.

6. Circumcision: Removing the foreskin of a penis and an almost universally accepted form of child abuse when the decision to perform this is imposed on boys unnecessarily, thereby mutilating them and reducing their full potential for sexual pleasure.

7. Border: A convention that often allows governments and people to treat people on the other side of an imaginary line as inferior and less worthy of compassion.

8. Soldier: A person whose country gives them permission to kill and destroy in the context of war (see above), as opposed to a defender (to which the term is often incorrectly applied) or a police officer.

9. Terrorist: Someone who perpetrates or promotes terror. As an adjective it can apply to many of the United Nations member states and to organisations, as well as to people.

- The economy: The intricate web of dealings that often make the rich richer and the poor poorer and to which most governments would sacrifice all decency and honour.

In conclusion, then, do not let words be your master because it is you who should be fully responsible for them and if you understand their magic, they can be veritable incantations for a brighter world.