"The Greatest Metaphysical Poet": Your Full Guide to John Donne’s Life, Career & Poems

Family background

John Donne was born in London in 1572 to a relatively wealthy family. His father, who died when Donne was only four, was a successful tradesman and his mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of the writer John Heywood. Both parents were Roman Catholics and were in obvious difficulty to come to terms with the newly established Church of England. Donne’s family, especially on his mother’s side, were persecuted for being Roman Catholics and for refusing to swear the Oath of Supremacy which acknowledged the English monarch as the Head of the Church of England.

This is the general atmosphere in which John Donne was brought up. As a child he was educated privately by Catholic tutors and at the age of twelve he was sent to Oxford University. The reason for attending Oxford at such a young age was due to the fact that all students had to pledge allegiance to the Queen and therefore to the Church of England by the age of sixteen. Donne’s mother was naturally hoping that her son would obtain a degree before that age. However this did not happen and the young student was eventually compelled to leave Oxford without a degree.

Hard choices

In the 1590s John Donne studied law at the Inns of Court. He was also very interested in theology and was extremely torn between the realities of the two religions which encompassed him.

He knew only too well that if he wanted to achieve any recognition and success he would have to convert to the Anglican Church. At the same time, he also realised that his mother’s family had undergone great suffering to be faithful to their Catholic faith.

The torment of this predicament came to an end after 1593, when his brother was caught harbouring a priest and therefore sent to prison where he died. The decision in favour of the Anglican Church must have cost Donne a great deal of suffering, but it certainly paved the way for social advancements. In 1595, his mother, who categorically refused to renounce her Catholic faith, abandoned London for voluntary exile.

In London Donne made many friends and soon became very popular in the fashionable society that mattered. He was described by a contemporary, Richard Baker, as “a great visitor of ladies, a great frequenter of plays, a great writer of conceited verse”. Donne also travelled to the continent, visiting Italy and Spain. He was on the right road to success.

In 1598 he was appointed Chief Secretary to the powerful Lord Keeper of England, Sir Thomas Egerton. By 1601 Donne was so well introduced that he managed to become a Member of Parliament. His success and future could have been, at this point, secured.

Part of the house where Donne lived in Pyrford.

Almost undone

Unfortunately, Donne’s greatest weakness, women, brought his downfall. In December of the same year Donne secretly married Lady Egerton’s niece, Anne More. When they were discovered, Donne was sent to prison and naturally lost his high position of Chief Secretary. The famous pun on the couple’s escapade portrayed their dismal situation: “John Donne, Anne Donne, undone”.

He was eventually forgiven but he was not given his job back. The couple had to leave London and lived in relative poverty, compared to their previous position. Donne’s situation changed after he decided to join the church as an Anglican Minister in 1615.

His life changed a great deal. Theology took the place of poetry. As he himself pointed out, he left “the mistress of my youth, Poetry” for “the wife of mine age, Divinity.” He still wrote some verse but his efforts were now focused on religious sermons and on preaching.

In 1621 Donne became Dean of St. Paul’s. He became very well-known for his fiery sermons and his sombre countenance. John Donne died in London on March 31, 1631.

His Literary career

Donne’s words on his rejection of “the mistress of my youth, Poetry” for “the wife of mine age, Divinity.”, exemplifies the development of his literary career. His early works, when he was seen as “a great visitor of ladies”, are made up of difficult and original love poems, some of which were even, at times, rather indecorous. The Elegies, the Satyres and the Songs and Sonnets were written during the 1590s and although not published (they were published in 1633, after Donne’s death), the poems circulated in manuscript form and became very well-known.

The most famous poems of this period, to mention but a few, are:

Songs and Sonnets

• The Flea, The Sunne Rising

• The Apparition

• The Good-Morrow

• Love’s Alchymie

• The Anniversarie

Elegies

• His Picture

• On his Mistris

• To his Mistris Going to Bed

Five Satyres,

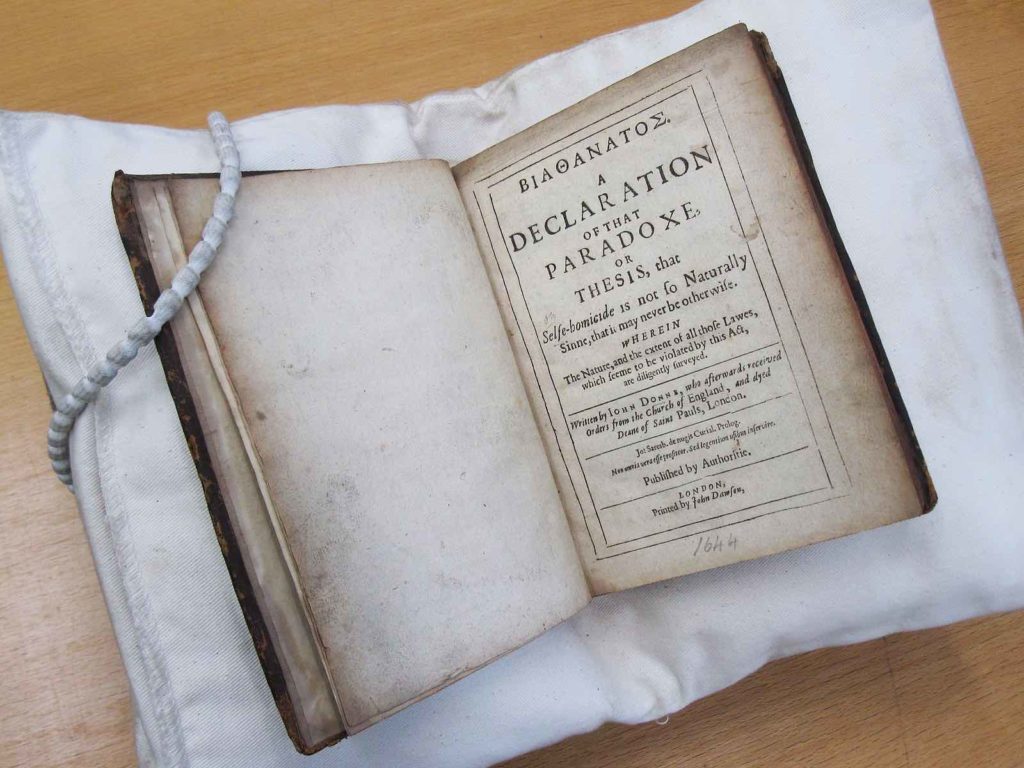

Biathanatos comes from the Greek and means “life and death”

Thematically, Donne’s poems take a twist for the Divine towards 1608, when he wrote Biathanatos, a treatise on the subject of suicide; Pseudo-Martyr, on the persecution of the Jesuits and their desire for martyrdom; and Ignatius his Conclave, written against the Jesuits.

The poems written in this period are known as the Divine Poems which include the Holy Sonnets or Divine Meditations. Among the Holy Sonnets the most widely read are certainly; Death Be Not Proud, a sonnet addressing death directly and challenging its ‘mighty’ powers; and Batter My Heart, a sonnet addressing the Holy Trinity. One of Donne’s most successful devotional poems on sin and forgiveness is A Hymnne to God the Father, in which the poet manages to blend humility with poetic force.

Donne’s sermons and meditations are certainly among the best ever written in this genre. As Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral, he preached magnificently and his considerations on death are clearly seen in his touching work, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions. John Donne’s final sermon at St.Paul’s, Death’s Duel, can almost be considered as being his own funeral sermon.

Style and Themes

Donne is the greatest of the Metaphysical poets and the acclaimed leader. The label ‘Metaphysical’ was coined for this school of poetry by John Dryden. In 1693, Dryden wrote about John Donne in his A Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire, stating that “…He affects the metaphysics, not only in his satires, but in his amorous verses, where nature only should reign; and perplexes the minds of the fair sex with nice speculations of philosophy, when he should engage their hearts, and entertain them with the softness of love.”

The Metaphysical poets wrote at a time when the world was witnessing a radical social and cultural revolution. All the truths and certainties of the Middle Ages had been shattered. The people who lived in the 16th century had been incessantly bombarded by new discoveries. In the late 15th century Christopher Columbus sailed beyond the horizon without ‘falling off’ the known world.

The earth, therefore, was not flat! A new world had been discovered. Other lands, therefore, existed beyond the horizon! Galileo challenged Aristotle and Copernicus challenged Ptolemy, declaring that the earth was not the centre of the universe and that, quite the contrary, it was just one of the many planets that revolve around the sun. The world, therefore, was not the be all and end all of existence! All these fallen pillars of what had been fundamental indisputable facts, left man disoriented.

The Metaphysical poets reacted to this disorientation by adopting a very realistic and intellectual poetic genre. The similes and metaphors used, were realistically extreme and often scientific. The poets sought to compare emotions with tangible realities that would never be confuted, as all the basic beliefs of the previous centuries had been. This type of simile or metaphor is called a ‘conceit’. Donne, for example, compares two lovers who are apart, to the legs of a pair of compasses and in another poem, he equates love to a flea.

The images chosen are all tangible realities, but unlikely comparisons. However, on closer examination all the images chosen have a distinct connection with what is being described. A compass draws a perfect circle, which is the symbol of eternity, so without mentioning anything so ethereal as infinity or eternity, Donne manages to express this through a scientific object, the compass. Furthermore, in order to exist, this drawing tool must be made up of two separate legs, hinged together. The two legs make the one tool. In this way he manages to express the ethereal notion of the oneness and unity of the lovers. To exist, they must be together.

The flea is another very strange image to use in connection with love. Yet here again Donne manages to show how this minute insect, after having sucked the blood of both lovers, represents their “marriage bed, and marriage temple”, and the oneness of their beings.

Another typical characteristic of the Metaphysical poets is their attitude towards love. The mellifluous lyric poetry of the Elizabethan tradition was certainly not for this literary school. Here again intellect and passion go on parallel tracks. Donne favours the sexual and physical element of love and only rarely does he praise platonic love. The Flea is a typical example of this, since in this poem Donne uses wit to attempt to persuade his mistress to have sex with him. A far cry from the sugary romantic poems of the cavalier poets of the 17th century.

Religious themes

The later religious poems of Donne, although thematically different, are similar in their use of conceits and in their dramatic introductions. The language naturally lends itself to religious and Biblical themes, often lifting directly from the Scripture. The terse direct style however remains the same. When he writes about death, for example, he does not use a sombre or overly spiritual tone. He addresses a personified death directly and rebukes him, calling him proud and belittling his power. The poet says that Death is a ‘slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men…’ Donne, therefore, maintains the metaphysical style even in his later religious poetry and in his sermons.

• We are delighted to announce that, following positive feedback, our literary column will now occupy a regular slot in The Gordian. The feature will be overseen by The Gordian literary editor, Alex Liberto and will include articles, literary pieces (including poetry), book reviews, interviews and competitions.