Voices That Shape Nations

Voices that shape us are all around us. In this issue of The Gordian magazine, we delve into the profound influence of diverse cultures and communities in the process of nation-building. From the tranquil mountains of Tibet to the vibrant streets of India, each article illuminates the unique contributions and challenges faced by these distinct groups in shaping the tapestry of our global society. This issue features articles by Alexander Stoney, Amy Church, Sunil Kumar Pariyar, Ellen Jones, Omar Alansari-Kreger and Carla Pietrobattista. The Editors are Ariana Yekrangi and Adrian Liberto.

Letter from the editors

Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi/UN-aligned

Welcome to this issue of The Gordian, titled “Voices That Shape Nations”. In this edition, we delve into the profound and often overlooked role that minorities play in the fabric of nation-building. Our world is a mosaic of cultures, each contributing uniquely to the narrative of history and the shaping of nations. This issue illuminates these diverse voices, offering insights into their struggles, triumphs and enduring spirit in the face of challenges.

The issue begins with Ariana Yekrangi’s piece, “How Tibet’s Peaceful Nation-Building Challenges Chinese Rule”. Here, we explore Tibet’s tenacious struggle for sovereignty, a testament to its enduring spirit and cultural heritage, standing resilient like the mountains that surround it.

Alexander Stoney’s “From Table Tennis to the UN: How Kosovo Used Sports for Nation Building” takes us on Kosovo’s unique journey. As a nascent nation, Kosovo has harnessed the unifying power of sports to carve out its place on the global stage, fostering national pride and international recognition.

In our editorial, “Bombing Civilian Areas & Killing Children is Wrong. Even for Revenge, Especially for Revenge”, we confront a harsh reality. This piece is a poignant reminder that the cost of conflict is often borne by the most vulnerable, urging us to rethink the consequences of revenge and violence.

Adrian Liberto’s “A Council in Deadlock: The UN’s Faltering Quest for Peace in Gaza” critically examines the UN’s struggles in Gaza. The article sheds light on the complexities and roadblocks in the path to peace, highlighting the limitations of international diplomacy in conflict resolution.

“The Green Divide” by Sunil Kumar Pariyar presents a thought-provoking perspective on Nepal’s conservation policies. It’s a narrative of conflict between ecological preservation and social justice, spotlighting the impact on marginalised communities caught in this delicate balance.

Amy Church’s “‘No Girl Left Behind’: How Taliban’s Ban on Girls’ Education Imperils Afghanistan’s Future” addresses a crisis of global significance. The absence of girls in Afghanistan’s classrooms symbolises not just a local issue but a worldwide failure, endangering the future of an entire generation.

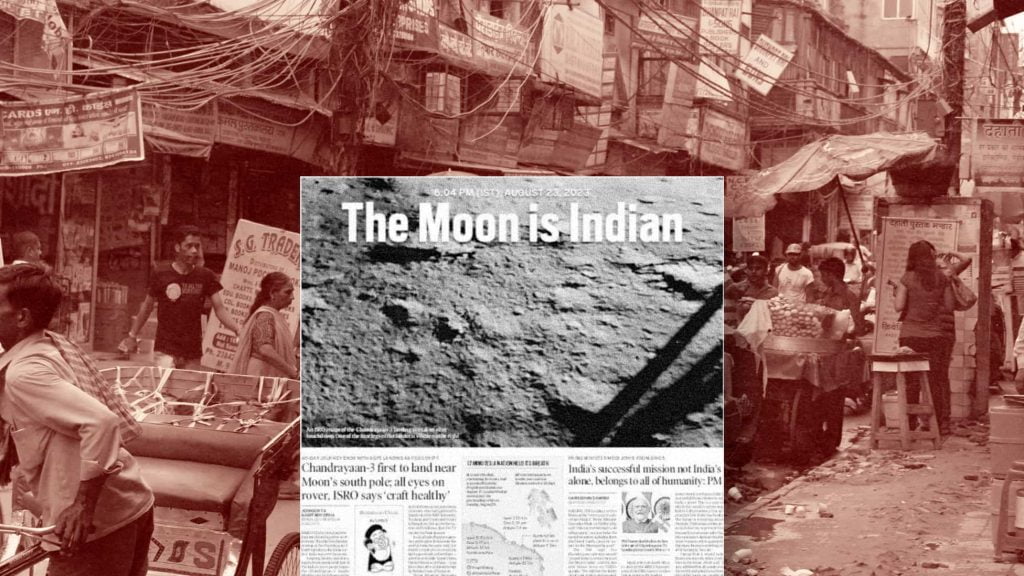

In “Behind the Headlines: India’s Rising Power, Lingering Poverty and the Quest for Balance”, Adrian Liberto takes us into the heart of India’s paradox – a nation soaring in global influence yet grappling with internal disparities. This piece explores the steps India must take to bridge this divide.

Ellen Jones’ “Nation-Building and Indigenous Struggles: Histories, Rights and Representation” delves into the land struggles of indigenous communities. From Palestinians to Māori, this article examines how these conflicts shape modern statehood and identity.

Omar Alansari-Kreger’s “Redefining Peacekeeping: The Case for a United Nations Corps of Peacekeeping Engineers” proposes a transformative approach to peacekeeping. This visionary piece suggests a shift from conflict containment to proactive infrastructural rebuilding.

Finally, Carla Pietrobattista’s “How Caravaggio’s ‘The Burial of Saint Lucy’ Transforms the Divine into the Earthly” offers an artistic interlude. This article explores how Caravaggio’s work reflects his personal struggles and his revolutionary use of light, grounding the divine in earthly realities.

Each piece in this issue of The Gordian offers a unique lens through which to view the intricate process of nation-building. Together, these voices shape not just nations, but our understanding of the world.

Thank you for joining us and happy reading.

How Tibet’s Peaceful Nation-Building Challenges Chinese Rule

By Ariana Yekrangi

Composite: Ariana Yekrangi

Despite relentless conquests, the struggle for Tibet’s sovereignty extends beyond the protection of its heritage; it’s a fight for the nation’s very spirit, enduring as the mountains that embrace it.

From Table Tennis to the UN: How Kosovo Used Sports for Nation Building

By Alexander Stoney

Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi/UN-aligned

As a young nation, Kosovo leveraged sports to establish international recognition, power, independence and national pride.

Bombing Civilian Areas & Killing Children is Wrong. Even for Revenge, Especially for Revenge

Ariana Yekrangi, Editorial

Vengeance rains from the sky, leaving a trail of innocence lost. Composite: Ariana Yekrangi

Two wrongs don’t make a right, particularly when the price is measured in the lives of children and the fabric of communities torn asunder.

A Council in Deadlock: The UN’s Faltering Quest for Peace in Gaza

By Adrian Liberto

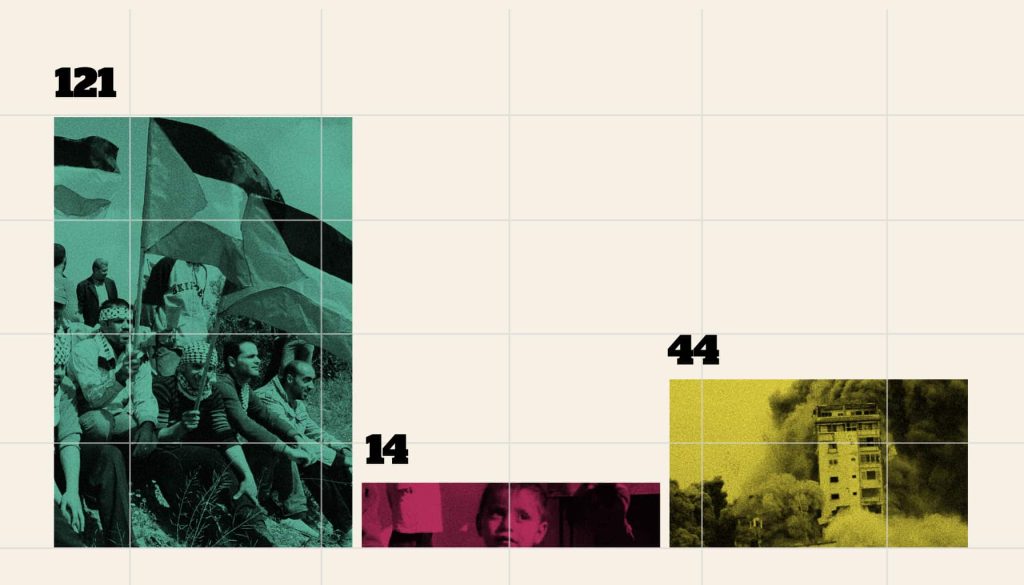

In a decisive vote for Gaza’s truce, 121 nations aligned for peace, with the US, Israel, and Hungary standing firm in opposition. The UK and Germany headed the list of 44 on the fence, marking a rift amidst global unity.

UN peace efforts in Gaza are criticised as Security Council vetoes block cease-fire moves and expose the General Assembly’s limited power.

Whilst the United Nations bats resolutions from one side of the Security Council’s court to another, people are dying in their thousands. This is not the United Nations; this is the Disunited Nations, failing in its primary mission of fostering world peace.

First, on October 16, a Russian-sponsored draft text, which had called for an immediate cease-fire, fell through because it did not manage to garner enough votes. Then, on October 18, the US vetoed a Brazilian draft that called for “humanitarian pauses” to allow unhindered humanitarian access.

On October 25, it was the US’s turn to be vetoed; this time by Russia and China. The draft was limited to just a pause to the fighting to allow humanitarian access, and the protection of civilians, but also pressed for a stop to the arming of Hamas or any Palestinian in the Gaza Strip. The same day, another Russian-sponsored draft failed.

In cases of paralysing stalemate at the Security Council, however, the United Nations General Assembly can step in… and so it did. On October 27 it passed a resolution tabled by Jordan calling for “an immediate, durable and sustained humanitarian truce leading to a cessation of hostilities” in Gaza and demanding that Israel rescind its order for the evacuation of northern Gaza.

The resolution passed with 120 votes for, 14 against, and 45 abstentions. There is nothing controversial about the ethics involved here, or the wording. Voting against such a ceasefire can only mean one two things: preferring war to peace, or wanting the obliteration of one or more parties. In this case it would seem as though the 14 countries who voted against the resolution, as well as the 45 who abstained, are quite happy to witness and support the genocide of the oppressed people of Gaza. The US, of course, not only votes against or vetoes anything aimed at resolving the situation fairly, it actively arms Israel and covers its back while it carries out its daily atrocities.

The passing of the resolution sent a clear message, but alas, unlike Security Council resolutions, General Assembly resolutions are not legally binding. So the good people of this world can only look on as the United Nations sits powerlessly in the face of this unfolding tragedy.

This is not to say that the organisation lacks people of goodwill who are doing all they can to stop the bloodshed. Secretary-General António Guterres is one of them. On October 24, he addressed the UN Security Council in no uncertain terms.

“It is important to also recognize that the attacks by Hamas did not happen in a vacuum. The Palestinian people have been subjected to 56 years of suffocating occupation. They have seen their lands steadily devoured by settlements and plagued by violence, their economy stifled, their people displaced and their homes demolished. Their hopes for a political solution to their plight have been vanishing. But the grievances of the Palestinian people cannot justify the appalling attacks by Hamas, and those appalling attacks cannot justify the collective punishment of the Palestinian people.”

His comments hit a nerve. Israel’s UN ambassador not only called for Guterres’ resignation, but also threatened to withhold the issuing visas to UN representatives… “to teach them a lesson.”

Not everyone, however, is willing to persevere in such a toxic atmosphere. Craig Mokhiber, for instance, who was the director of the New York office of the UN high commissioner for human rights, resigned after having written to the UN high commissioner in Geneva, Volker Türk, on October 28, lamenting the UN’s inability at stopping a “text-book case of genocide”.

The Green Divide: Social Fallout of Nepal’s Conservation Policies on Marginalised Communities

By Sunil Kumar Pariyar

Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi

Nepal faces a troubling conflict in its commitment to biodiversity conservation, as it struggles to balance ecological preservation with social justice amidst growing tensions between wildlife and local communities.

The value of protected spaces like National Parks is undeniable. Nepal’s journey with these parks began in 1993, when the Forest Act recognised certain ‘protected forests’ for their environmental, scientific and cultural value.

Once the royal hunting grounds, these spaces have evolved into critical conservation centres, forming a key part of Nepal’s forest management strategy. Today, Nepal boasts about 20 such protected spaces. However, while these parks aim for conservation, they also pose challenges, particularly for local communities with restricted access.

Living near these parks, locals face threats from wild animals, crop loss and human rights abuses, particularly amongst minorities and women. To address these issues, Nepal introduced ‘community forests’ around 25 years ago. These designated areas around the parks allow human activities, aiming to establish a harmonious relationship between humans and nature.

These areas also known as buffer zones sit between the parks and human settlements, reducing human-wildlife conflict and allowing sustainable forest resource use. Unfortunately, these buffer zones are far from perfect in addressing the issue.

The tragic reality of buffer zones

The community forest initiative, launched within buffer zones to support the Dalit community, has unfortunately fallen short of expectations. Its excessively protective approach has hampered effective implementation, making conservation and resource utilisation difficult.

Local women at the Baghamra community forest. Photo by Chandra Shekhar Karki/CIFOR/Flickr

In Nepal’s national parks and designated zones, groups such as Dalits and women who heavily depend on forest resources, not only wrestle with issues of gender-based violence but also face hostile treatment from park staff and military personnel.

The plight of these marginalised communities was shockingly underscored in 2010, when an incident in Bardiya National Park involving the assault and murder of three Dalit women laid bare the ongoing human rights challenges in these protected areas.

The management policy for these zones, ostensibly designed to conserve natural resources whilst supporting dependent communities, has unwittingly generated negative repercussions. By prioritising environmental issues, it overlooks the needs of Dalit women, thereby exacerbating inequality and restricting opportunities at the community level.

Local institutions, like the Management Committee and Users Group, prioritise park interests over those of community members, deviating from the government’s policy and operational process.

Even well-intentioned schemes, like homestays, stumble when trying to reach out to marginalised and impoverished communities. Homestays, a concept where tourists live with local families to experience their culture and lifestyle, were introduced in these zones as a means to boost local income. Yet, despite government efforts to elevate these living conditions for guests and subsequently increase local profits, the Dali and Madhesi communities often find themselves overlooked.

Local leaders justify this exclusion by citing these groups’ lack of financial capacity, while marginalised communities argue they have been deliberately left out of specific homestay training.

Wildlife vs livelihood: the struggle for resources

Communities within the buffer zone rely heavily on diverse professions like agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing and blacksmithing. However, park restrictions on forest resource use create significant resource access disparities, exacerbating the hardships of these already impoverished communities.

Dalits and Janajatis, in particular, face limitations in accessing resources and participating in decision-making within community forest programmes. This lack of access intensifies poverty and frustration, especially among the landless.

‘Community Forestry Meeting, April 2007: Dhading District locals discuss sustainable forestry and grassroots democracy against a backdrop of lush forests, despite a hiatus in local elections. Photo by Netra Sharma Sapkota, USAID/Nepal.’

Landless communities, particularly amongst the Dalit and Tamang groups, grapple with issues such as hunger and disease in their fragile, flood-prone homes and receive scant support from park authorities. Consequently, they find themselves pressured into low-income occupations due to their circumstances.

Furthermore, they bear the risk of wildlife attacks on their crops and livestock, a hardship that falls disproportionately on impoverished and Dalit communities.

Despite numerous compensation claims, responses are often dismissive or delayed. When compensation does arrive, it’s typically insufficient, stirring local suspicions of misappropriation.

Power, wealth and exclusion

Living in the buffer zones, communities are often reliant on forest resources, yet face considerable challenges. Antagonism from park staff and military personnel, combined with a skewed wealth distribution, places disadvantaged groups, particularly the Dalit and Madhesi Dalit communities, at a severe disadvantage.

Despite representation from diverse social strata, including upper caste Brahmin and Chhetri, as well as indigenous groups like Tharu and Janajati, the marginalised Dalit communities’ participation remains strikingly limited.

The current buffer zone community forest policy has significant implications for underrepresented groups, notably failing to consider the distinct needs of social groups such as the Dalit and Tamang communities.

These groups depend heavily on forest resources for survival, including sectors like agriculture, forestry and fishing. For instance, their reliance on firewood for cooking is not adequately addressed by the policy, which has not promoted alternatives like electricity-based cooking or biogas production sufficiently.

As a result, stark disparities in resource utilisation exist, exacerbating their frustrations over restrictive access to essential items like grass and firewood.

‘Dalit Women’s Land Claim Movement: 2.5 million Dalit women across 20 Indian states launch a major land rights campaign from April to December 2013, urging governmental action on National Land Reform Policy.’ Photo: ActionAid India - Campaigns/Flickr

Women, despite active roles in control, training and savings, are often confined to symbolic positions. Dalits and Madhesis, other disadvantaged groups, are mostly limited to savings and loan programmes, leaving them excluded from decision-making processes within the Community Forest Development Programme.

This reality contrasts starkly with the programme’s empowerment goals, revealing an undercurrent of protectionism that disproportionately affects the poorest and ethnic minority groups.

Our observations at Parsa National Park reinforced that bridging the participation gap in conservation programmes is essential. Therefore, the development of capacity-building initiatives aimed at empowering Dalits, women and other marginalised communities within the buffer zone holds immense significance.

The buffer zone policy currently prioritises natural ecosystems over human communities. Therefore, an urgent shift towards inclusive and socially equitable management strategies is required.

Such a transformation would foster active civil society participation in policy formulation and execution, moving away from the dominant exclusionary conservationist ideology towards a more holistic, inclusive approach to conservation policy.

Rethinking conservation

Addressing social issues within natural resource programmes in the agricultural and unequal context of Nepal calls for conceptualising and institutionalising social agendas at the governmental level.

This becomes particularly vital in the forest sector, where the political economy of aid and policy wields significant influence. My research and observations have triggered policy debates on strategies to counter the exclusionary outcomes of community-based natural resource management, including buffer zones.

https://un-aligned.org/climate-emergency/sunil-pariyar-on-dalit-and-danar-impact-in-nepal/

A pressing question that emerges is whether grassroots conservation interventions can truly benefit the poorest communities. This is especially pertinent when the existing institutional culture and knowledge system of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation may not be suitably equipped to manage conservation’s social issues.

Given the historical presence of exclusion at state, societal and household levels, interventions in the buffer zone must address exclusion from a structural perspective. Structural inclusion could provide economic and political opportunities to disadvantaged groups.

All stakeholders, encompassing the government, donors and non-state actors, need to re-evaluate exclusion in buffer zone programmes from a broader perspective.

This approach should consider the knowledge and power dynamics among individuals within a conservation organisation, along with the organisation’s role in policy planning and implementation.

The primary challenge lies in ensuring that buffer zone policies and programmes are socially inclusive. The dominance of a technocratic ideology and reliance on single-sourced scientific data in policy spheres contribute to the conservation-oriented nature of buffer zone policies and programmes. Thus, the concepts of inclusion and exclusion need to be integrated within the governance of government agencies, extending to the grassroots level.

The establishment of community forest networks, federations or institutions within the buffer zone is crucial to combat gender-based violence and optimise the use of buffer zone community forests. The local community would greatly benefit from support to establish such networks.

- Sunil Kumar Pariyar is a Dalit Forest Activist, nature conservationist and author from Nepal, who has dedicated over 15 years to the country’s Forestry Sector.

‘No Girl Left Behind’: How Taliban’s Ban on Girls’ Education Imperils Afghanistan’s Future

By Amy Church

Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi

The empty chairs in Afghanistan’s classrooms don’t just signify a local crisis; they mark a global failure that jeopardises the future of an entire generation and country.

Afghanistan’s education system

Afghanistan is currently the only country in the world where girls are forbidden to go to school. The decision to stop women being able to access school and university by the Taliban in August 2021, has consequently denied millions of girls their fundamental right to education.

Afghanistan has a complex and turbulent history and this has had undeniable consequences on its education system. The department of education was established in Afghanistan in 1913, with the goal of a national education system.

Efforts to expand and improve this occurred over the next 40 years, with girls allowed to access education, but this was frowned upon in comparison to their male counterparts. Internal conflict began in 1978, with disagreements between anti-communist Islamic guerrillas and the Afghan communist government leading to the overthrowing of the government in 1992.

This had an immense impact on the education system as there was no longer a uniform curriculum. The schools and universities were frequently closed and equal opportunities were not provided for boys and girls. Libraries were destroyed, and learning was not prioritised amidst the difficult living conditions.

By 1996, the country was divided into two military groups, the Taliban and the Northern Alliance. After the events of the 9/11 attacks the US intervened in the state of Afghanistan joining with the Northern Alliance. Thousands of teachers became victims of the war or left Afghanistan leading them to have a significant brain drain.

Girls’ education was banned under the Taliban rule, but many women continued to teach in secret. Eventually an agreement was reached and Afghanistan finally had a chance to begin rebuilding its fractured education system.

Afghan girls brave the classroom, challenging the Taliban’s restrictive religious and cultural beliefs regarding female education. Photo: Alejandro Chicheri, USAID

During this pro-western period new schools were built and thousands of girls previously banned from education, once again had the opportunity to learn. Despite this, many families were still afraid to send their daughters to school, fearing the risk of kidnapping and sexual assault.

Gender disparities and cultural barriers

The gender gap in education therefore remained, it is evident from a young age, but it especially begins to widen around the age of 10, reaching a peak at the age of 14.

There are a number of conflicting factors that inhibit girls’ access to schooling. Girls from poor households in rural areas of the country were especially likely to drop out of school. It is worth noting however, that in Afghanistan there were also large numbers of girls from wealthy households in urban areas that were also not in school. This suggests that gender was the most significant factor in children being out of school, regardless of their financial situation.

Some religious beliefs in Afghanistan assume that girls are only meant to be protected inside the house and this has to an extent discouraged families from sending their daughters to school. Further to this, the problem is accentuated around adolescence as a result of Afghan cultural norms.

According to UNICEF, around 50% of girls are not aware of what menstruation is when they have their first period, this leads to them being confused and embarrassed. They are not aware of the normality of menstruation and are not provided with the support and facilities they need, and this consequently impacts their eagerness to attend school.

As a result of the previous conflict, there was a small proportion of female teachers within the education system even during the Western leaning leadership, and this means that young girls are lacking role models. It may lead to them viewing learning as something for boys, and something that is not suited to them, once again disillusioning them from education. Girls’ schooling remained a problem, but accessibility was improving during the Western leaning administration.

Consequences of the 2021 US withdrawal

The withdrawal of the US troops from Afghanistan in August 2021 once again placed the education system in a precarious place. Whilst the Taliban agreed that they would not place a ban on girls schooling, once the Taliban took back their control, a ban was immediately placed. At the moment, girls have no opportunity to pursue an education.

President Joe Biden meeting with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah. On the 8 July 2021 Joe Biden expresses doubt over the potential of a Taliban takeover, deeming it ‘highly unlikely.’

The impacts of this ban are detrimental and widespread. Young girls feel hopeless and demoralised, many of them are keen to have careers in the future such as being doctors or lawyers, activists or environmentalists, but these dreams have been stripped from them.

Girls have stated that ‘their life has no meaning without education’ and that every house is now filled with ‘pain and sorrow’. It is difficult for women to remain hopeful, when their right to education is repeatedly being taken away from them. It strips women and girls of their identity and purpose; they may feel as if they have no reason to carry on when the future looks so bleak.

Women are tied to their homes, unable to have the career they want or better themselves through a degree. Instead they have no choice but to be tied to men, unable to leave their houses without a male chaperone, they have little freedom or independence, and little hope for the future.

Broader impacts on Afghan society

It is not only women that are impacted by the ban on education, it risks severely affecting the country of Afghanistan as a whole. If half of the population remains uneducated, then far less people are able to work hence negatively impacting the economy of the country.

Educated women are able to contribute to problem solving for crises such as climate change, and would be fundamental in shifting social and cultural norms to ensure more equality within Afghan society. It has been suggested that Afghanistan risks a lost generation since educated women are fundamental for its development. It is impossible for the nation to advance if women continue to be excluded from education and public life.

UNICEF reveals Afghanistan’s 2.5% GDP loss due to girls’ education exclusion, with potential US$5.4 billion boost if current three million girls complete secondary education. Photo by EC/ECHO/Pierre Prakash © CC BY-ND 2.0 Deed

Save the Children have also highlighted that child marriage rates and poverty will soar if the ban is not lifted. Uneducated girls are more likely to be forced into marriages against their will, and these can often be dangerous and limiting for them. Currently, 54.5% of the Afghan population live below the poverty line, and the number of people living in extreme poverty will only continue to grow if nothing is done to stop the ban on girls’ education.

Attempts at intervention and their limitations

Whilst unsuccessful efforts have been made to re-open access to schools and universities, the ban still remains. The power that the Taliban hold makes the situation extremely difficult to navigate for international organisations as well as individual activists.

The political nuances mean that there is not a straightforward solution to the problem. The United Nations attempted to intervene, given that the ban is a clear violation of human rights, however it was not successful. A ban on all non-governmental organisations within the country by the Taliban has further limited the help that other actors are able to provide.

The Malala Fund has offered $1 million in grants to help education champions and their families evacuate and resettle, they have also supported Afghan education activists and put pressure on the Taliban to reverse its decisions.

Our role in the crisis

We have an international responsibility to help girls and women in Afghanistan; the devastating situation cannot be ignored anymore. Attempts should be made to increase the pressure on authorities in Afghanistan in order for the ban to be lifted and so that a safe commencement of girls’ education can occur.

Additionally, if the ban is to be lifted immediate financial support will be needed in order to support a crumbling education system, organisations should work to ensure that they are able to provide this. Furthermore, where possible it is important to show solidarity with Afghan activists and amplify their voices so that they are able to share their demands for the future.

The severity of this situation, with millions of girls being denied their right to education, cannot be ignored. Currently, the Taliban is continuing to strip girls and women of their basic rights and the world is watching it happen. Some efforts have been made, but we must continue to push forward and demand change if the ban is to be lifted.

As individuals, we should use the freedom we have to ensure the same for others, this can be done by joining and sharing campaigns, supporting activists and writing to local members of parliament and leaders to ask what they are doing to help. Global leaders, organisations and individuals need to show up in this time of crisis, in order to ensure that no girl is left behind.

Behind the Headlines: India’s Rising Power, Lingering Poverty and the Quest for Balance

By Adrian Liberto

Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi/UN-aligned

India ascends on the world stage, projecting power and prosperity, yet within its borders, the stark reality of disparity and unfulfilled promises persists. What are the steps forward?

Nation-Building and Indigenous Struggles: Histories, Rights and Representation

By Ellen Jones

Aboriginal leader at the 13th Canadian Aboriginal Festival.

How do the enduring land struggles of Palestinians, Māori, Sami and First Nations define the modern state?

In an era where borders are drawn and redrawn, the quest for a homeland remains fraught with strife for many. Nation-building, the process of constructing a national identity and establishing political and social structures, is pivotal in this quest. It is not just about hotly-debated independence stories or drawing lines on a map; it involves acknowledging diverse histories, cultures and rights to create a cohesive and inclusive society. This is crucial for ensuring peace, stability and progress.

Cultural resilience in Canada, treaty negotiations in New Zealand, the defence of Arctic pastures by the Sami and the interplay of history and rights in Israel-Palestine — each of these scenarios paints a vivid picture of nation-building.

Israel-Palestine enduring conflict

On October 7, Hamas carried out a deadly operation on Israel, which the Israeli government described as the “worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust”, resulting in over 1,400 civilian deaths and 200 hostages on the Israeli side. In response, Israel declared war, conducting constant air strikes and blocking supply lines of basic necessities to the Gaza population. As of November 8, Palestinian authorities have reported that 10,515 individuals in Gaza have perished, with children accounting for nearly half of the victims. A humanitarian crisis is escalating as Israel tightens its hold on the territory.

Young girl holding a Palestinian flag at a rally. On Hamas’s October 7 attack in Israel led to over 1,400 civilian deaths. Israel’s response: war, air strikes, and Gaza blockades, resulting in 10,515 Palestinian deaths, nearly half children, escalating a humanitarian crisis.

Examining historical claims is essential for understanding the tensions between the two sides. Palestinians assert their historical connection having lived in those lands for countless generations, while Jewish claims are rooted in ancient and religious traditions that were born and nurtured in those territories from the dawn of their history until the diaspora.

Significant historical milestones, such as the 1917 Balfour Declaration issued by Britain sought to establish “a national home for Jewish people” in Palestine, leading to the drive for sole sovereignty over a nation that was predominantly Arab.

The conflict’s complexity is tied to political representation, influencing nation-building and conflict resolution. Discriminatory measures in Israel’s government (Knesset) limit the expression rights of Palestinians. The 2018 nation-state law established Israel as the state of the Jewish people, reinforcing inequality, integration and impacting resource allocation for Palestine.

International law plays a pivotal role in recognising indigenous and minority claims during nation-building. The 1993 Oslo Accords, an agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) established a Palestinian Authority (PA) which provided limited self-governance over parts of the West Bank and the Gaza strip. However, it failed to adequately address crucial issues like indigenous land and Palestinian rights, leading to unresolved conflicts and societal discord.

Various peace efforts have attempted to find a lasting resolution but have failed due to regional power dynamics and global influence, risking a wider regional conflict in the Middle East. For example, the 2000 Camp David Summit between US president Bill Clinton, Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak and the PA chairman Yasser Arafat failed to reach a final agreement. Additionally, the 2002 Roadmap for Peace presents the vision of the two states, Palestinian and Israeli, living side by side in peace and security. This, despite the difficulties involved, remains the best hope for a lasting solution to the conflict.

Māori rights and recognition

The ongoing conflicts faced by the Māori people in New Zealand highlight the challenges in recognising indigenous claims in nation-building endeavours. Their historical claims to ancestral lands originated 800 years ago and clashed with European colonisation, creating struggles for rights, land ownership, cultural heritage as well as political autonomy.

Maori assembly on the porch at Pāpāwai’s Kotahitanga Parliament House opening, with Richard John Seddon on the left. 1897. Pāpāwai, once the heart of the Maori Parliament, deteriorated post-World War One.

New Zealand has made commendable progress in acknowledging the Māori’s rights and cultural significance, granting them a degree of territorial autonomy through settlements and governmental partnerships.

Political representation acts as a catalyst for positive change thus empowering the Māori people in decision making processes and increasing the nation’s social cohesion. The Māori Representation Act in 1867 allotted four seats for Māori members, however this was still not proportional to their population, therefore in 2018 it increased to 29 Members of Parliament with Māori background. This aimed to foster integration and social cohesion within New Zealand.

International legal mechanisms, notably the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, paved the way for a nation state and was an agreement between the British Crown and Māori to build a British government giving Māori the ownership of their lands. Moreover, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), has significantly reinforced Māori rights, which has fostered harmony between indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

Despite these efforts, debates persist regarding the interpretation of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi. In recent years there has been a division between Māori and others, concerning the balance between indigenous rights and democracy in the nation.

Sami arctic struggles

The ongoing conflicts involving the Sami people and the Israel Palestine situation reveal shared struggles for indigenous rights and cultural preservation within the context of nation-building efforts. Both indigenous communities leveraged historical claims to their lands, the Sami in Arctic regions and Palestinians in Palestine. They have both experienced and confronted discriminatory policies that threatened their way of life; in regard to the Sami, this affects their livelihood, which revolves around reindeer herding, fishing and hunting.

Nation-building efforts for the Sami, as with similar groups, are hindered by limited political representation and fragmented political structures. However, efforts have been made to empower the Sami community leading to the establishment of Sami parliaments in 1999. This serves as vital bridges between Sami communities and governments.

Sámi Parliament of Norway © Sámediggi Sametinget/Flickr

The Sami parliaments showcase the resilience and cultural richness of the Sami people, demonstrating how Indigenous governance can thrive in the modern era. However, despite their endeavours in education, cultural, and environmental protection, debates over land use and the forced assimilation of the Sami still stand.

The contemporary struggle for resources and pressure of global economic demands has driven profit-driven industries to clear and log forests located in the Sami land for timber. This exploitation threatens one of Europe’s most indigenous communities, eroding their identity, land, and culture through endangering species such as lichen, a vital source of food for reindeer.

Sami leaders say that their right to self determination and identity is being seized by a lack of progress on land rights. This diverts their attention from other serious environmental issues that also threaten their way of life and their very existence. The pressure of the green energy transition and the attractiveness of the open northern tundra increases pressure on the Sami community. Finding a balance between economic development and the preservation of indigenous heritage is crucial in resolving the conflicts faced by the Sami people.

First nations identify quest

The conflicts between First Nations in Canada and those facing Palestinians share similarities. In both cases, historical claims underpin the conflicts, with indigenous peoples asserting their connections to their ancestral lands through cultural practices and religious traditions. These claims have been critical in justifying their presence and shaping international recognition. However, dismissals of these assertions have fuelled tensions and ongoing disputes.

These challenges in political representation impact nation-building and conflict resolution. This is exemplified by Canada’s treatment of its indigenous populations, characterised as “cultural genocide” by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015. In 1920, Duncan Campbell Scott, the Canadian Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, stated the government’s policy: “Our objective is to continue until there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.” They thus expected that this minority group would eventually disappear.This restricted the autonomy of First Nations communities, limiting their authority over indigenous territories, and essential services like education and healthcare. Here too, then, the resulting inequitable socio-political landscape exacerbates conflicts and hinders an inclusive nation.

First Nations Protesters Drumming at Vancouver Women’s March. Photo: William Chen © Wikimedia

Historic peace efforts, such as the 1899 Treaty 8, are significant as they illustrated attempts at lasting resolutions with the colonial government who promised to protect their rights to hunt, fish and trap. The 1973 Calder case played a crucial role in recognising indigenous claims and emphasised the first recognition of First Nations’ historical claims to the land. However, implementation challenges persist due to historical injustices and territorial disputes.

Similar to many other treaties in Canada, these have been a subject of ongoing debate and legal interpretation concerning the rights and responsibilities of both Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government. Today, systemic discrimination persists and there is a lack of support for First Nations in adapting to the growing concern of food scarcity related to the impacts of climate change.

In conclusion, the histories and ongoing struggles of indigenous and minority groups in nation-building processes across various regions, from the Palestinians and Māori to the Sami and First Nations, highlight the critical importance of recognising and integrating their distinct rights and cultural identities. These examples underline why nation-building that is inclusive of minorities is not just an idealistic pursuit but a necessity for creating peaceful, stable, and equitable societies. As these groups strive for recognition and representation, their struggles serve as a reminder of the need for a more inclusive approach to nation-building that respects diversity and fosters genuine harmony.

Redefining Peacekeeping: The Case for a United Nations Corps of Peacekeeping Engineers

By Omar Alansari-Kreger

Graphic: UN-aligned design team.

A proposed UN Corps of Peacekeeping Engineers could shift the focus from mere conflict containment to active infrastructural revival in war-torn states.

Civilisation cannot be achieved without modern infrastructure. In one way or another, there will always be infrastructural failures impacting the development of nations. Can one nation have too much infrastructure? How do nations overbuild themselves to points of sprawling ostentation? The image of the United Nations peacekeeper is routinely overshadowed with powerlessness and melancholic despair.

Their purpose is to keep the peace under shaky truces prolonging geopolitical stalemates as things in society go from bad to worse in failed state realities. UN peacekeepers are not builders. They are placeholders with little to no power to influence the restoration of peace. Is it possible to “civilianised’’ military power for peaceful purposes in conflict zones steeped in crises?

Revival of world federalism depends on ideas that make supranational cooperation possible. Once this is achieved, strides toward actual union become increasingly possible.

Ezequiel Padilla, Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs, signs the UN Charter on 26 June 1945 at the Veterans’ War Memorial Building. This followed the San Francisco Conference where fifty nations unanimously agreed on the Charter, which took effect on 24 October 1945. Photo: UN/Flickr

Since the ratification of the United Nations Charter on June 26th, 1945, how many world federalists were daring enough to imagine a United Nations Corps of Peacekeeping Engineers? Is it possible for such a supranational body to be equally answerable to the General Assembly and the Security Council simultaneously in lieu of the current organisational structure of the United Nations?

The Security Council has done everything but prevent war in the interest of world peace. It has continued the work of divide and rule, inspired by former European colonial powers by supporting authoritarian regimes to advance their competing national interests.

A Security Council would make sense if each member state was bound by international law to a commitment of peace regardless of national interest wherever and whenever there is war. Realpolitik is governed by the dog-eat-dog psychology of the enemy of my enemy is my friend resulting in obscure geopolitical entanglements, where peace is sold as an empty commodity to the highest bidder so long as authoritarian leaders organise their totalitarian governments to fall in line.

No peacekeeping mission is complete without an unconditional commitment to a failed state’s civilian infrastructure reconstruction and development. Inspiration for a possible UN Corps of Peacekeeping Engineers is derived from the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

In forward operating areas, army engineers perform vital services such as detecting environmental hazards and demining operations to protect advancing forces while building fortifications to protect vital field assets such as communication and medical centres.

On 19 August 1945, the 1269th Engineer Combat BN docks in Antwerp Harbour, Belgium, ready to board a troopship for their journey home. © CC BY-SA 4.0

During World War II, the United States 1269th Engineer Combat Battalion, in conjunction with the 101st Airborne Division, successfully recovered looted art treasures found in Hermann Goring’s home in Germany on May 5th, 1945; everything from rare paintings to fine carpets were recovered and returned. The corps was routinely tasked with finding stowaways hiding vital war resources and Nazi war criminals themselves in newly captured territory.

Their findings testified to the murderous greed of the Nazis in their insane efforts to rewrite European history. What could a UN Peacekeeping Engineer Corps achieve in failed states, active war zones, and no man’s lands when applied in similar capacities? Such a proposition cannot be entertained without raising a series of successive questions related to the “infrastructural comeback” of failed states:

Could conventional peacekeepers provide the security necessary for a team of peacekeeping engineers to repair and rebuild bombed out bridges separating cities, communities and their families?

Could peacekeeping engineers be tasked with building water wells and desalination centres in rural areas steeped in drought?

Could peacekeeping engineers rebuild, renovate and expand over capacitated power plants to minimise brownouts to improve quality of life where there is critical infrastructure underdevelopment?

In the United States, the army corps of engineers has as many civilian roles as it does military, with one of its central missions dedicated to maintaining the socioeconomic wellbeing of the nation. According to the United States Bureau of Reclamation, 1200 dams, 153 hydroelectric power plants, and 25000 miles of navigable waterways throughout the continental United States, is managed and maintained by the US Army Corps of Engineers as of 2022.

United States Army Corps of Engineers headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia in 2016. © CC BY-SA 4.0

This is suggestive of “nation building psychology,” but the big picture question is: how can the same psychology be applied and reimagined as a pillar of world peace to build a better, more responsive United Nations to deny causes for war in a final bid to end geopolitical crises at their source? How can the Security Council successfully make that transition by becoming a true supranational peacekeeping organisation via the UN Peacekeeping Engineer Corps, unhindered by rivalrous foreign policy interests?

How Caravaggio’s ‘The Burial of Saint Lucy’ Transforms the Divine into the Earthly

By Carla Pietrobattista

Caravaggio’s portrayal, St. Lucy forsakes heavenly glory for a gritty burial scene, which reflects the artist’s personal struggles and innovative use of light. Graphic: Ariana Yekrangi/UN-aligned

Caravaggio’s portrayal, St. Lucy forsakes heavenly glory for a gritty burial scene, which reflects the artist’s personal struggles and innovative use of light.

Breaking from iconic traditions

Both artistic and sculptural representations traditionally depict St. Lucy in celestial grandeur. She is often shown holding the palm of her martyrdom, which occurred in Syracuse in 304, in one hand, and a saucer containing her eyes in the other.

This iconographic element is a nod to her role as the protector of sight, although it bears no relation to the martyrdom she endured. The origin of this specific veneration is tied to her name: Lucy, or Lucia, derives from the Latin term ’lux,’ meaning light—an element naturally associated with eyesight.

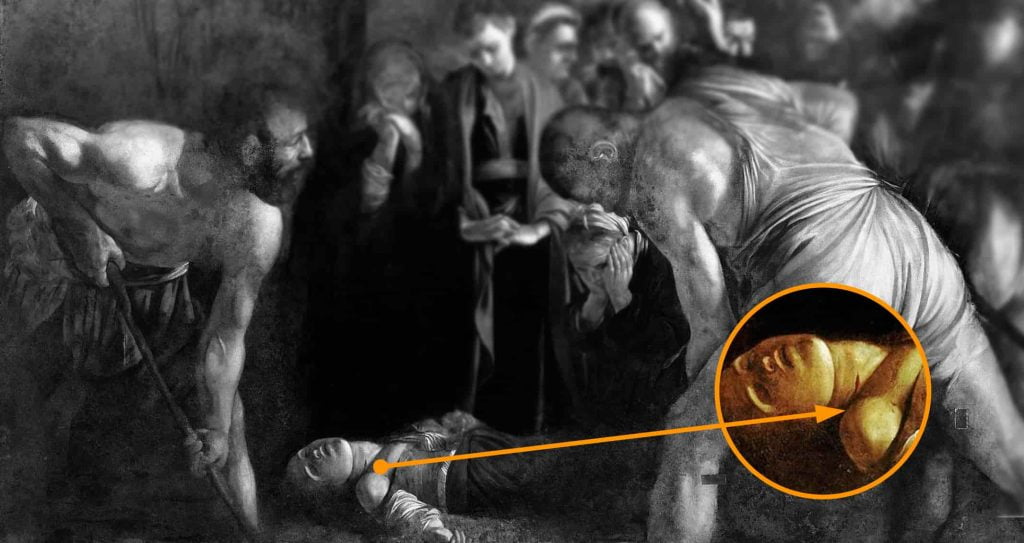

Breaking away from this established tradition is the Burial of Saint Lucy by Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio. Painted for a church dedicated to the saint from Syracuse, this masterpiece marks a stark departure as it presents St. Lucy not in heavenly glory but in the solemn moment of her burial.

Santa Lucia Alla Badia Church, the home of Caravaggio’s ‘The Burial of Saint Lucy. Photo: Zde/Wikimedia

Personal struggles shape art

Considering that Caravaggio’s presence in Syracuse is documented shortly after his departure from Malta, where he had taken refuge following his death sentence in Rome, the work was almost certainly created in 1609.

This period coincides with a particular moment in the artist’s life, in which the dramatic evolution of his complex personality is widely witnessed in his final works, in which he actually overturns his own vision and conception of artistic construction.

In this canvas, every single scenic or technical element testifies to and amplifies the strong inner turmoil of the artist. The artist is fully aware of his death sentence, and makes death, in particular the beheading to which he was sentenced, an element that is not only conceptually unavoidable but also indispensable in his artistic production.

Evolution of light and shadow

The space in which the burial scene is set has nothing in common with the “full” and dense spaces of his Roman works.

The environment is deliberately empty, both to fully convey the idea of the arcosolium of the catacombs present at the site of Lucy’s martyrdom and to focus the observer’s attention on the protagonists of the painting, all positioned in the lower part of the canvas.

As in the case of ‘Conversion of Paul’, where immediate attention is directed more at the horse than the saint; here too, the gaze falls more on the two men positioned next to her body, busy digging the grave that will receive the young woman’s corpse.

Two men dig a grave, seemingly detached, as Lucy appears with a near-severed head from a stab in the throat.

Lucy, killed by a stab in the throat (jugulatio), appears with her head almost severed by the force of the blow, ending up, albeit less conspicuously, among the many severed heads obsessively depicted by Caravaggio in the last years of his life.

The two men mechanically perform their movements without the slightest emotional participation, just as had already happened in the Roman painting depicting the martyrdom of Peter, where the executioners seem focused only on the material operation of raising the apostle’s cross, without an awareness, or at least cognisance, of their act.

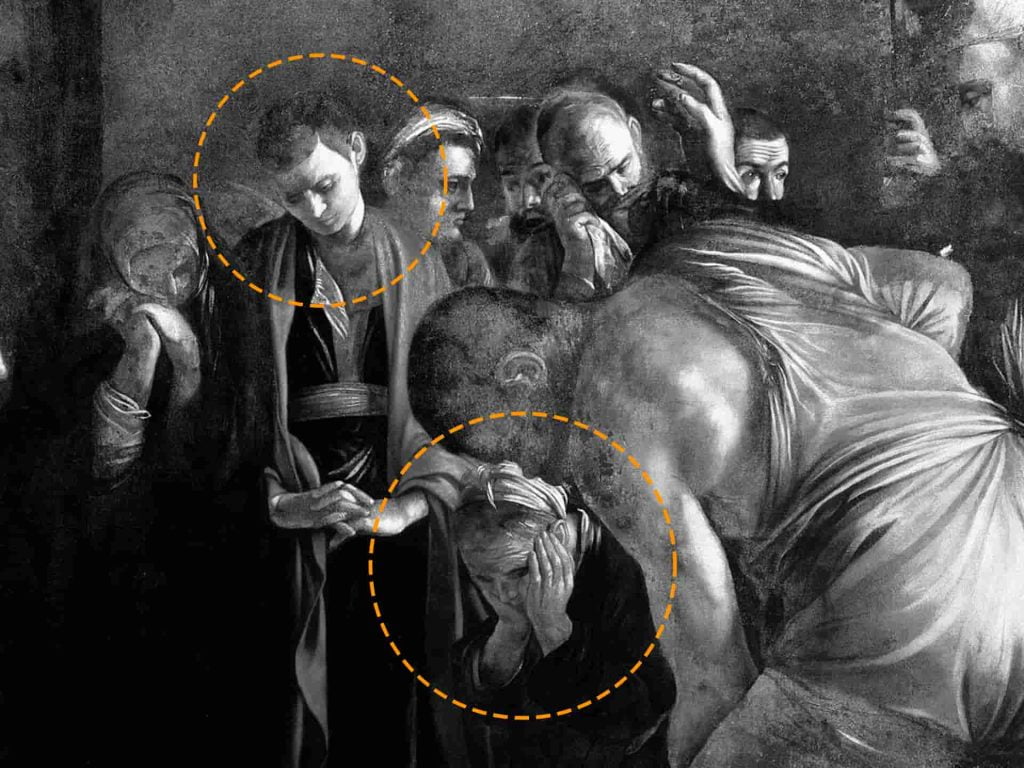

In the Syracusan canvas, rather than expressing pain, the characters surrounding the blessing bishop display a calm displeasure mixed with resignation. The feelings appear so superficial that they cause most of the characters to lose their individuality and definition in the composition.

The only person who seems to experience genuine grief is an elderly woman, kneeling beside Lucy’s body, who, in disbelief and dismay in the face of the saint’s violent death, has her hands on her face, with a gesture very similar to one already proposed by Caravaggio in a female figure present in the scene of the ‘Beheading of the Baptist’.

Elderly woman displays genuine grief amid stoic onlookers, mirroring a similar pose in Caravaggio’s ‘Beheading of the Baptist.

Caravaggio, always free from any pre-established schema, only cites himself in his works of artistic maturity. Hence, Lucy’s body, devoid of vital strength, is depicted without the serene composure, ideal and idealised, of the martyrs present in the works of other artists, but with the exposed shoulder and the same abandonment, the same dramatic truthfulness of the Virgin in the canvas ‘Death of the Virgin’.

Just as the events of the artist’s private life reveal more than one Caravaggio, his works exhibit the same versatility. It is as though within a single man, a single body, several souls and personalities find space, capable of generating beauty and death with the same intensity.

Caravaggio, in his art, never looks outside himself but draws from his own soul, his own feelings, his own art. Each of his paintings not only tells the stories of its characters but becomes a clear reflection of the evolution of the author’s character and experiences.

Caravaggio’s flight and torment are not only manifested in the repetition of beheading scenes, but also find expression in the new way of presenting and perceiving light, the principal element and guiding thread of his entire artistic production.

Unlike his earlier art, where light and shadow were clearly separate, here they blend together. This shift in lighting style mirrors Caravaggio’s personal struggles, creating an atmosphere where life and death feel equally present.

Compared to the Roman works, the light in his last works loses intensity, becoming dramatically and inexorably rarefied, as if it were no longer distinct and opposed to darkness.

In Caravaggio’s early works, shadow and light, even if clearly defined and in a certain sense distinct, were at each other’s service. In the artist’s final works, however, these same elements become one, merging into a single entity, where it is not evident where the shadow gives way to light.

This is much more than an expressive technique; it is the reflection of a soul where the immediacy of life and the absolute certainty of death coexisted with equal strength and urgency.

Thank you for reading The Gordian Magazine.