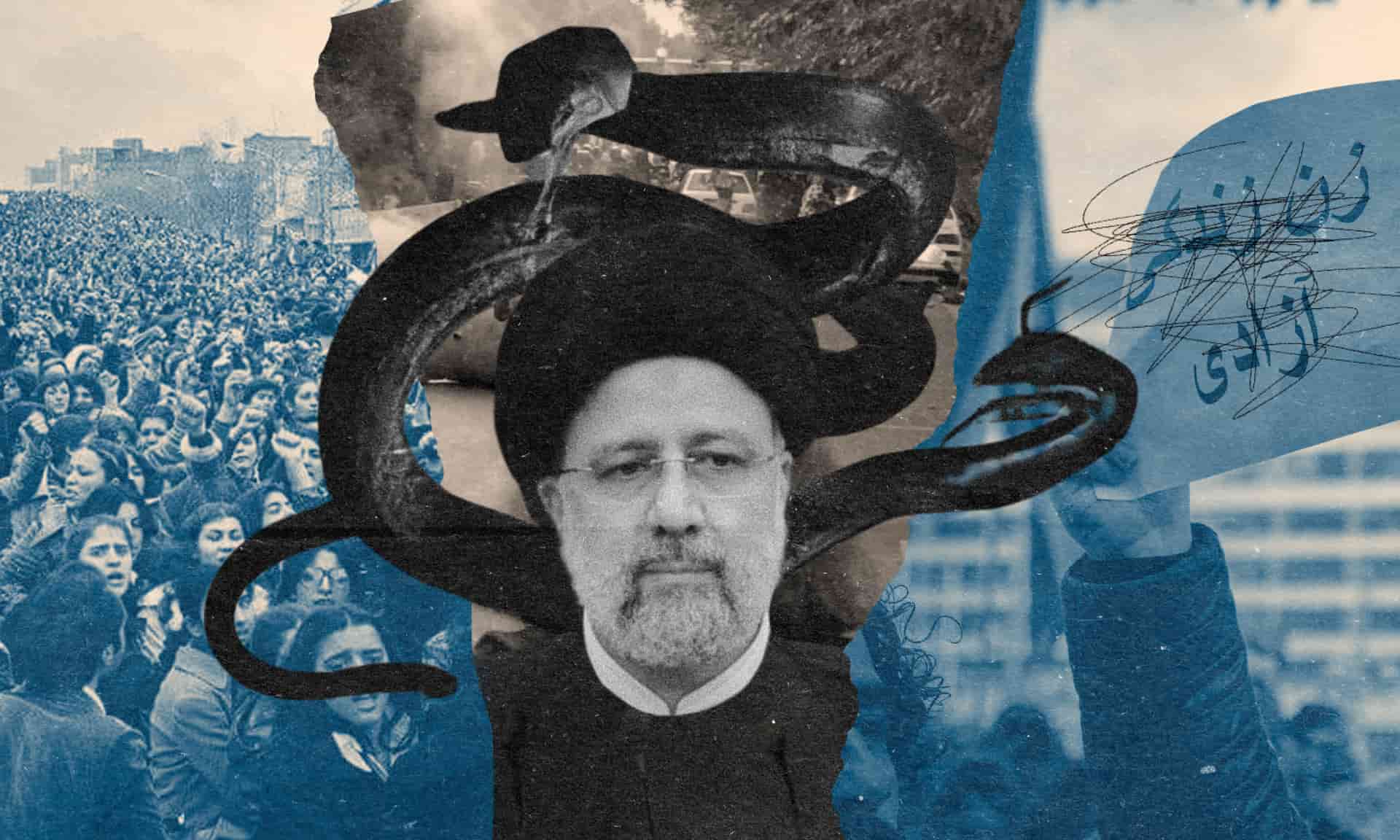

From Zahhak to the Islamic Republic of Iran: Has Ferdowsi prophesied the future of the republic?

In his national epic, the Book of Kings, Ferdowsi, tells us a story of a kingdom ruled by hungry snakes terrorising a nation. Little did the poet know that 1000 years later, his national epic would become a prophecy.

Zahhak was the evil king of Mesopotamia who conquered Iran and, together with his army and serpents that grew out of his two shoulders, terrorised the people of the land for thousands of years. It all started when in order to congratulate the new king on his new position, the embodiment of evil, known in the Book of Kings as Ahriman, disguises himself as the royal cook and asks to kiss the new king’s shoulders. Zahhak agrees and moments after Ahriman’s lips touch Zahhak’s shoulders two black snakes emerge.

All attempts to remove the snakes from Zahhak’s shoulders proved futile, for as soon as one snake head had been cut off, another would take its place. The king was counselled and the only solution was to keep the snakes well fed, but these snakes summoned by Ahriman were no common snakes; they did not crave mice, but rather lusted for human brains. In fact, two young men’s brains were prescribed as daily food to keep the serpents happy and satisfied, or else the beasts would feed on king’s own brain.

According to Ferdowsi, Zahhak’s reign over the kingdom was a bleak and cold time for the land during which the sun refused to shine:

“Zahhak reigned for a thousand years, and from end to end the world was his to command. The wise concealed themselves and their deeds, and devils achieved their heart’s desire. Virtue was despised and magic applauded, justice hid itself away while evil flourished; demons rejoiced in their wickedness, while goodness was spoken of only in secret.”

The story of the Islamic Republic of Iran is eerily similar to Ferdowsi’s national epic. Much like the serpents on Zahhak’s shoulders, religion has been sitting on one side of the Islamic Republic’s shoulders and power lust is parched on the other, both feasting on terror and torture for over 40 years.

A new wave of protests: “Women, Life, Freedom”

In November 2022, a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa Amini, was on a family trip to Tehran when she was stopped by the morality police, who enforces the Iranian government’s conservative dress codes for women. Despite her family’s stentorian protests, she was nevertheless driven to prison. Amini was admitted to the hospital “without any vital signs and brain-dead” within hours after that and was pronounced dead three days later. Authorities say Amini died of a heart attack caused by underlying health problems, but her family has fiercely refuted such assertions.

Though the story is distressing, for many women in Iran, being abused and, both literally and figuratively, beaten by the words of “god” is a daily occurrence. I have lost track of the number of times my mother and female friends have been arrested and bullied by the Iranian police. Since the 1979 revolution, torture and public executions have been rife in the country.

Amini’s tragic death wasn’t unique: it was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Soon after Amini’s death, nationwide protests spread as far as 80 cities. According to some reports, hundreds may have been killed and many more have been imprisoned, while the Iranian government has blocked access to the internet and social media.

Iran has a long history of policing what women can and cannot wear; first prohibiting the hijab in the 1930s and then making it mandatory after the 1979 revolution. The details and implementation of the required dress code have changed over time, however, regulations have been tougher under the hardline President Ebrahim Raisi.

Protests have previously been successfully suppressed by the Iranian authorities. When claims of election fraud pushed millions to the streets in 2009, the military opened fire on the demonstrators. Many were killed, others were jailed, and dissidents were tortured and raped. Reuters reported that protests against rising oil prices in 2019 were met with an even harsher response, with the Revolutionary Guards killing 1,500 people.

What happened to Zahhak will one day happen to the Islamic Republic of Iran

So back to our story about what happened to Zahhak. One day, imperial orders were issued requiring Kaveh Ahangar, a common blacksmith, to sacrifice the brain of his last daughter for the king’s snakes. Kaveh and his wife were already bereaved, Zahhak had already taken 16 of their 17 children.

Having spent all night on the roof of his house seeking solutions to save his last daughter from Zahhak’s snakes, inspiration struck. Instead of sacrificing his daughter, Kaveh sacrificed a sheep and put its brain into the wooden bucket. Those who were aware of the ruse were utterly surprised as the snakes did not notice the difference. The trend grew popular and following the same trick, the town managed to save the lives of hundreds of other children.

Of course, these children had to be pronounced dead, so spared children were sent to the safety of the Zagros Mountains, where no one would find them. It was hoped that one day they would return to their homeland and save their families from the tyranny of Zahhak.

That day eventually came. The destiny of the demon snakes was to be unveiled. Kaveh and the children drew near Zahhak’s castle and both men and women left their fields to join them in the fight against evil. The large crowd surged forwards and smashed the castle gates. Kaveh raced down the winding stairs straight to Zahhak’s chamber and, with his blacksmiths’ hammer, cut off the evil snake-king’s head, thus putting an end to his demonic tyranny.

The news of Zahhak’s demise spread across the land and men and women drank and danced to the sound of flutes and drums, their arms outstretched like eagles soaring to the skies. They were now free. The day that Kaveh defeated Zahhak is celebrated in Iran as Nowruz, the ‘New Day’ or the Persian New Year.

Much like Ferdowsi’s story, religious leaders in Iran have been tyrannically ruling over the country taking away human rights, in particular those of women, the LGBTQ+ community and those belonging to religious minorities. For Ferdowsi, Zahhak’s story is a metaphor for a despotic regime that has to take lives every day in order to secure its survival.

Despite the Iranian government’s efforts to suppress dissent, an increasing number of people are uniting in the condemnation of authoritarian oppression, with demonstrations becoming normal and accelerating at a fast pace.

The death of forced religion and with it, the Islamic Republic, will mark another chapter in Iran’s history, which will no doubt be celebrated.