What is the difference between the ICJ and the ICC?

Justice is not a relative term, but for much of our history we have manipulated it to such an extent that we have created a parallel sort of justice. More often than not, human justice is just a sinister doppelgänger of justice in its purest form. This is because human justice depends on laws, and as we all know, laws are biased. The justice of the Inquisition, a sharia court or the sham courts of dictatorial regimes are based on very different laws and therefore profess their own unique brands of justice. The one main thing that they do have in common, though, is that they are self-serving. Being tried by a self-serving court is not justice, but rather, quite the opposite, namely, injustice or anti-justice. However, laws are not the only factor influencing justice, as the mechanisms that are in place to apply these laws also play a crucial part in the administration of justice.

International Law

In this article I would like to focus on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC). Both are contingent on international law and the first test of their fairness lies in the validity and integrity of these laws. The main sources of international law are, according to the Statute of the ICJ as:

- International treaties and conventions;

- International custom as derived from the “general practice” of states; and

- General legal principles “recognized by civilized nations”.

These laws are also influenced by political and legal theories as well as expertise and interpretations offered by international law scholars. Many reflect the 1920 Statutes of the Permanent Court of International Justice, as part of the Covenant of the League of Nations. Indeed, it would take several experts to evaluate these effectively, nevertheless, one does not need to be an authority in this respect to identify some of the glaring weaknesses.

Where are the international laws to prevent ecocide or animal exploitation, for instance? Or where is the law that forces the 70 plus nations that discriminate against LGBTQ+ people to stop doing so? The United Nations argues that its Declaration of Human Rights is “unequivocal” when it claims that: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” This is nonsense! How else could over a third of its Member States get away with criminalising homosexual acts?

As for the mandates, mechanisms and functions of the ICJ and the ICC, they are very different, as are their successes and failures.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ)

Unravelling the UN

(This section on the ICJ is taken from my book Unravelling the United Nations)

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is “the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.” It took over from and “is based upon the Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice” that was established by the League of Nations in 1920. “The Court’s role is to settle, in accordance with international law, legal disputes submitted to it by States and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized United Nations organs and specialized agencies.

The Court is composed of 15 judges, who are elected for terms of office of nine years by the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council. It is assisted by a Registry, its administrative organ. Its official languages are English and French.”

Thus, the ICJ has two main roles, namely: settling disputes that are presented to it by the countries that are involved in conflict (contentious cases) and advising on issues referred to it through UN channels (advisory proceedings). It is therefore very different from the International Criminal Court [ICC], which only deals with individuals…

The ICJ can only adjudicate when all the States involved in the case in question have accepted the court’s jurisdiction. This may be done in three ways:

- “By entering into a special agreement to submit the dispute to the Court;

- By virtue of a jurisdictional clause, i.e., typically, when they are parties to a treaty containing a provision whereby, in the event of a dispute of a given type or disagreement over the interpretation or application of the treaty, one of them may refer the dispute to the Court;

- Through the reciprocal effect of declarations made by them under the Statute, whereby each has accepted the jurisdiction of the Court as compulsory in the event of a dispute with another State having made a similar declaration. A number of these declarations, which must be deposited with the United Nations Secretary-General, contain reservations excluding certain categories of dispute.”

After a case has been submitted to the judgement of the court, the States involved are expected to abide by its decision. Should a party wish to ignore the rulings of the court, the other party may call on the Security Council to intervene:

“If any party to a case fails to perform the obligations incumbent upon it under a judgment rendered by the Court, the other party may have recourse to the Security Council, which may, if it deems necessary, make recommendations or decide upon measures to be taken to give effect to the judgment.”

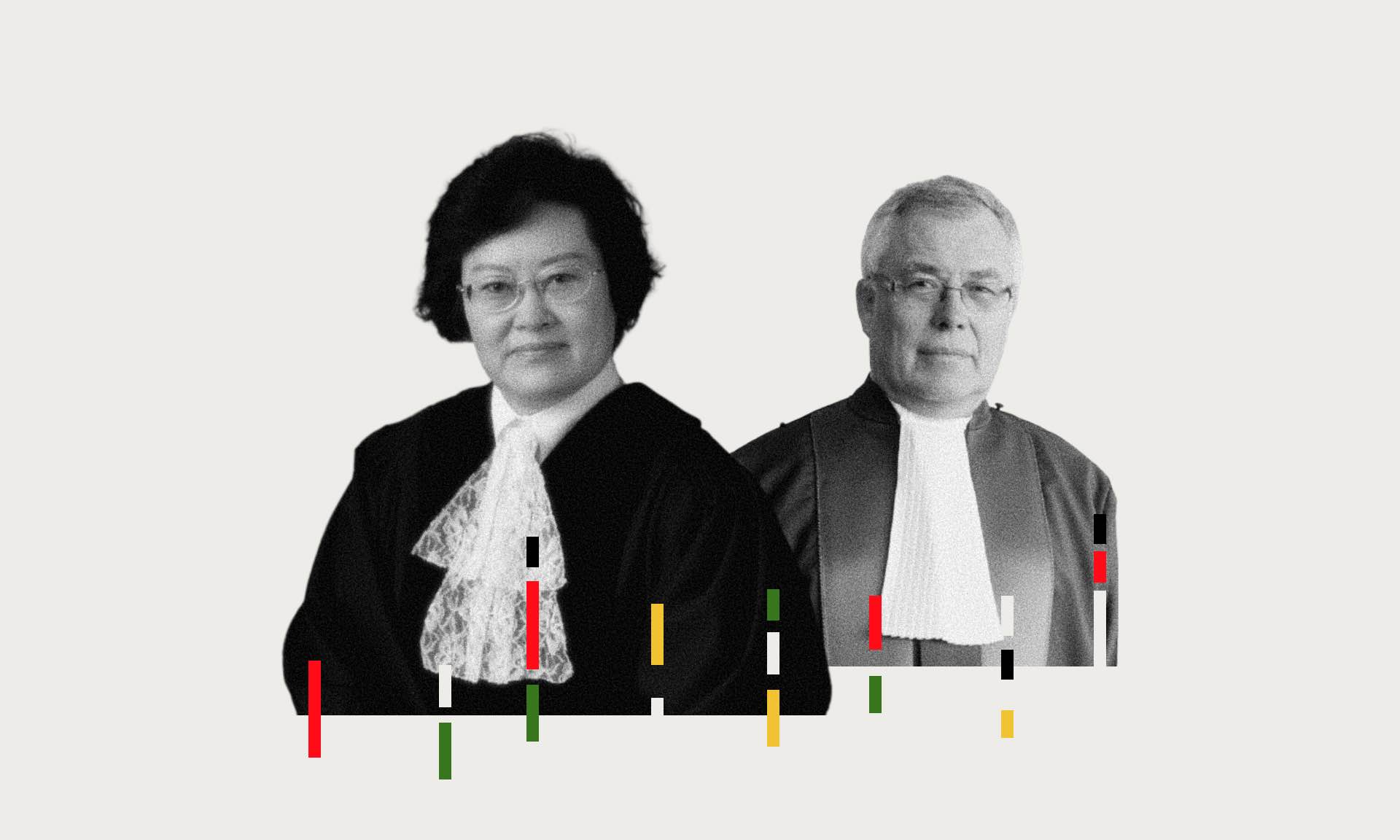

Permanent members fo the Security Council, can easily dismiss the decisions ICJ

The Security Council, however, may also choose to dismiss the decisions of the court through one or more of its permanent members, even if these members had previously submitted to its jurisdiction. This happened spectacularly in 1986, with the case of Nicaragua versus the United States. Nicaragua had filed a case against the USA accusing it of mining its ports and of supporting the Contras in their attack on the legitimate government of Nicaragua. Owing to the USA’s previous acceptance of the Court with regards to the jurisdiction over such disputes, the suit was considered valid, despite the USA arguing against this. The ICJ had the final word because its Statute specifies that in case of doubt, it is up to the ICJ to decide whether its jurisdiction was lawful or not.

The US withdrew its previous commitments that were applicable to the case, but the ruling went ahead. The USA was ordered to terminate its aggression against Nicaragua and to pay reparations. The US refused to comply and “vetoed” the ruling on 28 October 1986. Two other permanent members of the Security Council – the United Kingdom and France – abstained, as did Thailand. A few days later, on 3 November, the General Assembly voted by a majority of 94 to 3 on a resolution (A/RES/41/31) calling for the USA to respect the ruling. Only El Salvador and Israel joined the USA in voting against the resolution.

The UN list of ICJ rulings does not even include the Nicaragua versus the United States case. This is because, in 1978, the ICJ decided that only cases that were accepted by responding parties should be included. As such, it only publicises its successes. The same does not apply for advisory proceedings, however, and the Court’s opinions are listed in these cases, as the recent conclusions on the issue concerning the Chagos Archipelago indicates.

The Chagos Archipelago, the largest island of which is Diego Garcia, remained under British control when Mauritius received its independence in 1965. The British proceeded to change its name to the British Indian Ocean Territory [BIOT], deport all of its residents (about 1,500 people) and set up a US/UK military base.

The UK was “under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago”

On 25 February 2019, the ICJ found that “the process of decolonisation of Mauritius was not lawfully completed when that country acceded to independence”. It therefore concluded that the United Kingdom was “under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible.” The UK Government, however, made it immediately clear that it would disregard the advisory verdict. Soon after the decision, Karen Pierce, the UK Permanent Representative to the UN, declared that: “the United Kingdom has no doubt about our sovereignty over British Indian Ocean Territory”.

These affairs do not only exemplify how self-interest can take precedence over justice; they also highlight how UN institutions can be undermined by the very nations that helped create them. They also expose the weakness of the Court, in as much as it depends on the goodwill and the willingness to comply of all the parties involved.

The International Criminal Court (ICC)

The ICC is very different from the ICJ, although it is easy enough to confuse the two courts. The fact that both are headquartered in The Hague, in the Netherlands, has added to the confusion. The ICC was set up by the Rome Statute in 1998 and only began operations in 2002. Its purpose is specifically to judge individuals accused of committing serious crimes, namely: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes of aggression and offences against the administration of justice. While all UN member States “are ipso facto parties to the Statute” of the ICJ, the ICC is not an organ of the UN, nor is it universally recognised. Nevertheless, the UN Security Council is one of the authorities that can trigger a trial; the others being a State party and the actual Prosecutor.

When it comes to defining specific crimes, the ICC is unambiguous, which is not surprising considering the extent of violence involved. In all, however, the ICC has only managed to indict 45 people, although most are tried in absentia and never brought to justice. Many cases are also dropped due to a lack of sufficient evidence. Successful convictions include the first in 2006, that of Thomas Lubanga Dyilo for war crimes committed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the last, Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi (in 2016), a Tuareg Islamist responsible of war crimes in Mali.

One of the main problems is that State cooperation is necessary for the ICC to mount successful cases. Without this, the court would face several problems, including reaching the convict and the necessary witnesses. Cases are therefore often cherry-picked, with many centring around Africa. Another problem is that when people in power are convicted in absentia, they then become desperate to cling on to power at all costs in order to avoid being extradited to face justice, as was the case with Omar al-Bashir of Sudan. Most concerning is the fact that investigations can take decades to conclude. This is obscene. No wonder so many of those indicted die before their case is concluded.

In 2012, Jon Silverman, writing for the BBC, highlighted the main issue:

“The International Criminal Court (ICC) currently has an annual budget of over $140m (£90m) and 766 staff. Since its inception, its estimated expenditure has been around $900m (£600m). With only one completed trial to show for a decade of effort and expenditure, the ICC has faced regular criticism that it sucks in investment with few results to show for it.”

The situation is no better today. The ICC’s budget for 2021 is €148,259,000, and with about 14 ongoing investigations, that is over €10.5 million a case. Moreover, six of those cases date back to over a decade since the investigation opened. The overall cost per case is therefore a good deal higher. One may argue that the existence of the court itself serves as a deterrent and that its value should therefore not be judged by the number of investigations alone. However, with so few success stories to speak about, it is highly unlikely that the ICC constitutes much of a deterrent.

International Justice: Are we better off without the ICJ and the ICC?

On the one hand, until we have a better system to replace them, the answer is ‘no’; but on the other, if they lead us to sit back complacently thinking that they are the solution to international justice, the answer is ‘yes’. Something better is clearly needed: a justice system that is founded on clear ethical principles that do not need decades to unravel and effective mechanisms that cannot be undermined by Nation States.

How to achieve a robust legal system? Solutions towards comprehensive global justice