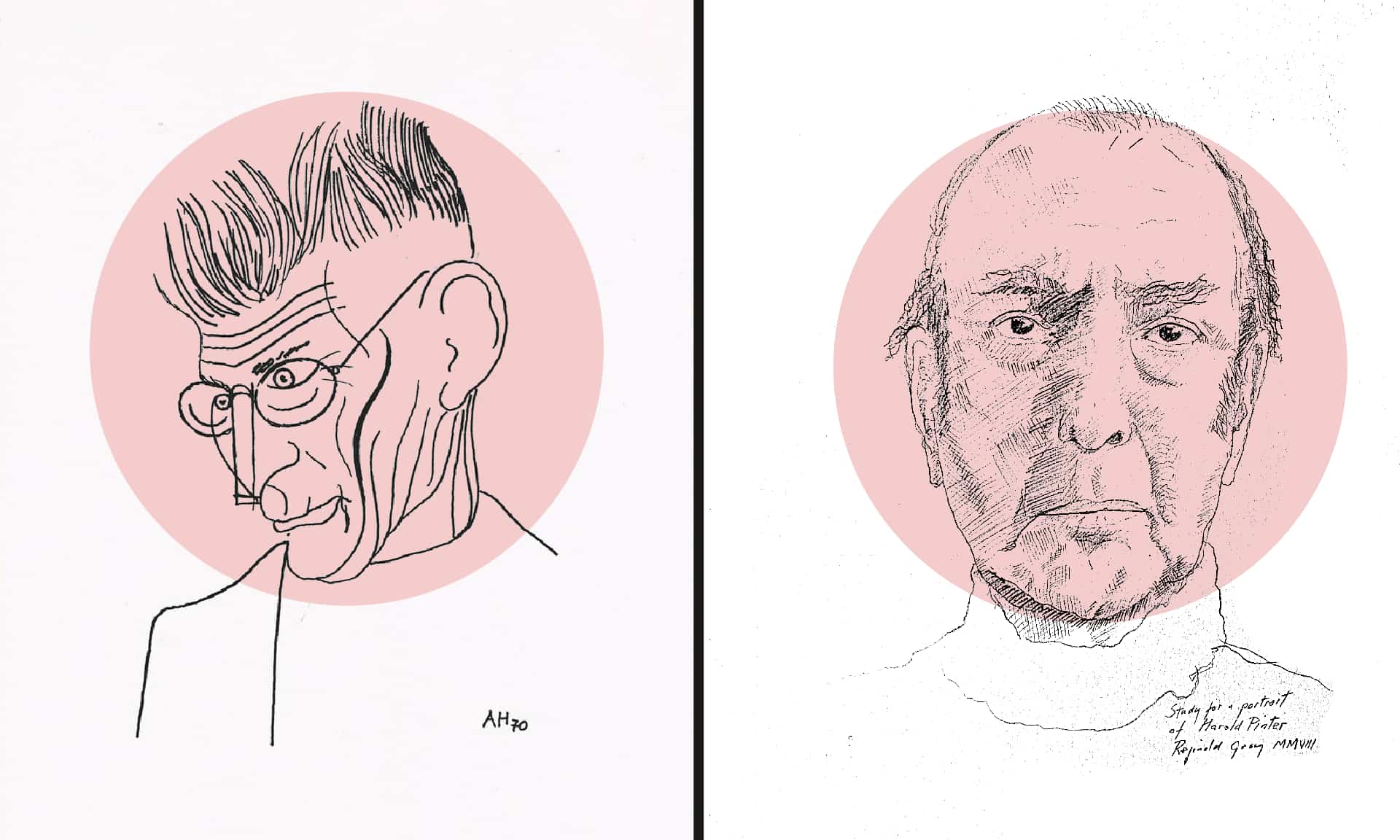

Samuel Beckett & Harold Pinter: 2 Giants of the Theatre of the Absurd

In the last issue we saw how some 20th century writers envisioned a dystopian future in reaction to the two world wars and to the dwindling human values. Protesting against society and the situation of man, but in a different way, were the giants of the Theatre of the Absurd Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter. Both playwrights developed a new drama which was characterised by features that had nothing in common with the prevailing criteria of the time.

Samuel Beckett: Waiting endlessly

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1952) shocked the traditional critics who desperately searched for plot, characterisation, orchestrated dialogue or just a plain simple story - and found none. This new drama, known as the Theatre of the Absurd, was in fact the incarnation of the imperceptible situation man found himself in during the post-war society; so imperceptible in fact, that the characters of Beckett’s play are surrealistic, as are their incoherent dialogues and the setting itself.

Time loses all sense and meaning. In two days, a dead, withered tree regains its full bloom. Two characters, Pozzo and Lucky, who were normal on the first day, both have disabilities on the second, Pozzo is blind and Lucky is dumb. What is more surprising is that we learn that they have been blind and dumb for a long time. This surrealistic quality of the play is also evident in the static development of the two main characters, Vladimir and Estragon. They talk to each other but they do not communicate. They take decisions which they never follow. They wait endlessly for Godot who never appears. The whole work is more like dramatised poetry, or music.

Herbert Blau, who directed the play for 1400 convicts at San Quentin penitentiary in 1957, compared the play to a piece of jazz music in which one could search for any interpretation of feeling or understanding. Referring to jazz, which is characterised by improvisation and not altogether harmonious rhythm, helps us understand the definition of Absurd which, in musical terminology, actually means out of harmony.

Beckett’s Style and Themes

Although Beckett wrote many novels and extremely interesting experimental fiction, his acclaimed works are his plays. The innovative nature of his style and content resulted in controversial critical analysis. The term, Theatre of the Absurd, was coined by the Hungarian-born critic Martin Esslin, in the light of the study of Albert Camus on the human situation during the socio-political tumult and existential turmoil of the 1940s. Camus had described the separation between man and his environment in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). This is how he diagnosed the disharmony in an alien world:

A world that can be explained by reasoning, however faulty, is a familiar world. But in a universe that is suddenly deprived of illusions and of light, man feels a stranger. He is in an irremediable exile, because he is deprived of memories of a lost homeland as much as he lacks the hope of a promised land to come. This divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, truly constitutes the feeling of Absurdity.

The situation that man found himself in was one in which all ideals and values had vanished. Millions of Jews were killed by the Nazis. Hundreds of thousands were killed by the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hundreds of thousands were killed in their own home or in the air raid shelters by the falling bombs. There was no comfort in religion.

Nietzsche had once proclaimed that “God is dead” and the situation after the second World War was so bleak that his ominous words were taken to be true. Beckett saw man as “a scrap of life surrounded by death, a something encircled by nothing”. This desperate and disharmonic situation is clearly portrayed through the Theatre of the Absurd, which presents the exact opposite of how traditional plays should be structured.

A good traditional play should have a well constructed plot, Beckett’s plays do not. A good traditional play should have intelligent dialogue and subtle characterization, Beckett’s characters ramble on mechanically and incoherently. A good traditional play should develop a theme from an introduction to a conclusion, Beckett’s plays have no introduction and no conclusion.

Judged by the standards of the Theatre of the Absurd, Beckett’s plays were masterpieces. They seemed to be chunks of dreams, or nightmares, stolen from the subconscious and re-presented in writing. From those dreams and nightmares Beckett shed light on themes of loneliness, isolation and suffering. He exposed the difficulties in which humans found themselves; isolated, faithless, and without any ideals or values to help bear the pain and solitude.

The dreamlike surrealism of Beckett’s plays makes them more of tangible “ideas” than anything else. Even his play Endgame wallows in surrealism. It is about a blind man with legless parents who live in dustbins and a son-cum-slave who incessantly endeavours to run away but, like Didi and Gogo, is helpless and cannot act.

Beckett purposely intended his plays to be the tangible representation of the isolation and suffering of man. He therefore wanted to avoid style and high-flown language which he thought would shift the focus from the real essence of his aim. To do this he first wrote his plays in French, an acquired language, and then he translated them into English. In this way he was forced to concentrate on syntax and clarity of language.

Thanks to Beckett and to the other avant-garde playwrights of the Theatre of the Absurd, the theatre no longer had that sophisticated middle-class traditional setting and that conventional development which was so typical until then. Playwrights like Beckett, Ionesco, Genet and Pinter took the theatre beyond the parameters of convention into a world with no God, no ideals, no values, no logic. An absurd world.

Harold Pinter: “A way of being able to look at the world…”

Harold Pinter’s plays belong to the Theatre of the Absurd in that they express visually what is felt poetically. His characters, like Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, speak in non sequiturs and are unable to explain their actions.

Pinter’s characters are even more inconsequential when they converse. They just talk for the sake of talking. This Pinteresque style of dialogue, as it has come to be known, is really typical of the disharmony Pinter wanted to portray. He saw man as an object that simply existed. He echoed Beckett’s description of man as “a scrap of life surrounded by death, a something encircled by nothing”. In The Homecoming one of the characters attacks his family with words which could very well have been expressed by Pinter himself in relation to man.

You wouldn't understand my works. You wouldn't have the faintest idea of what they were about [...] It's nothing to do with the question of intelligence. It's a way of being able to look at the world. It's a question of how far you can operate on things and not in things [...] You're just objects. You just [...] move about. I can observe it. I can see what you do. It's the same as I do. But you're lost in it.

Pinter’s Styles and Themes

Pinter belongs to the Theatre of the Absurd and owes a lot to Beckett. However, he has his own original characteristics which make him quite unique. Most of Pinter’s earlier works studied the themes of contrasting situations based on the known and the unknown. The “known” expresses tranquility and uncomplicated existence while the “unknown” is the threat which undermines that existence. Due to this threatening outside situation, his early plays were called Comedies of Menace. As the unknown loomed over the characters they became increasingly more vulnerable and disorientated. Thus, through their struggle to re-establish their safe and uncomplicated existence, Pinter dissects existential themes of loneliness, death, meaninglessness of life, communication, sexuality, and human relationships.

A typical characteristic of Harold Pinter is his ability to describe the raw reality of life’s stereotypical repetitive nature, highlighting at the same time the sense of doom and danger hovering overhead.

Pinter is also quite unique in his use of language. He skilfully zeroes in on the lack of rationality in man’s life through the use of language, or many a time, through the absence of language, hence the renowned expression, ‘Pinter pause’. This extreme use of silence as a tool to convey certain messages is evident in many plays. In _A Slight Ache_, for example, the growing tension between a husband and wife is exasperated by the use of unbearable silence. He also uses outside effects like sudden banging or calling, to obtain that threatening feeling of doom.

The Pinteresque language is generally colloquial and repetitive and the dialogues are inarticulate and often banal. It is, however, this banality of natural speech which enhances the depth and strength of the emotional potency.

Harold Pinter’s original portrayal of common people, who attempt unsuccessfully to communicate and whose existence seems to be totally futile, represents a milestone in the history of drama.