British Drama in the Age of Self-Discovery: Significant Plays and Key Themes

Uncovering the hidden gems of 20th century British drama.

In last month’s issue we surveyed the two literary genres of poetry and the novel at the turn of the 20th century which we defined as an Age of Self-Discovery.

We saw how the tide began to change during the last two decades of Queen Victoria’s reign, when some writers sought a newer and fresher approach to literature.

We then surveyed the literature that developed with the onset of the First World War, which had triggered in man the awareness to see life as an abyss of incessant self-discovery.

British drama was not as thriving and dynamic as poetry and prose during the first decades of the 20th century. Following the successful era of naturalism during the end of the previous century, the theatre was left staggering to find its new identity and to shake off the brazen, banal and often exaggerated realism, which had contaminated the world of drama.

In the early 20th century some playwrights reverted to symbolism and dramatic fantasy with escapist plays like Peter Pan, by Sir James Barrie.

The Irish Literary Theatre

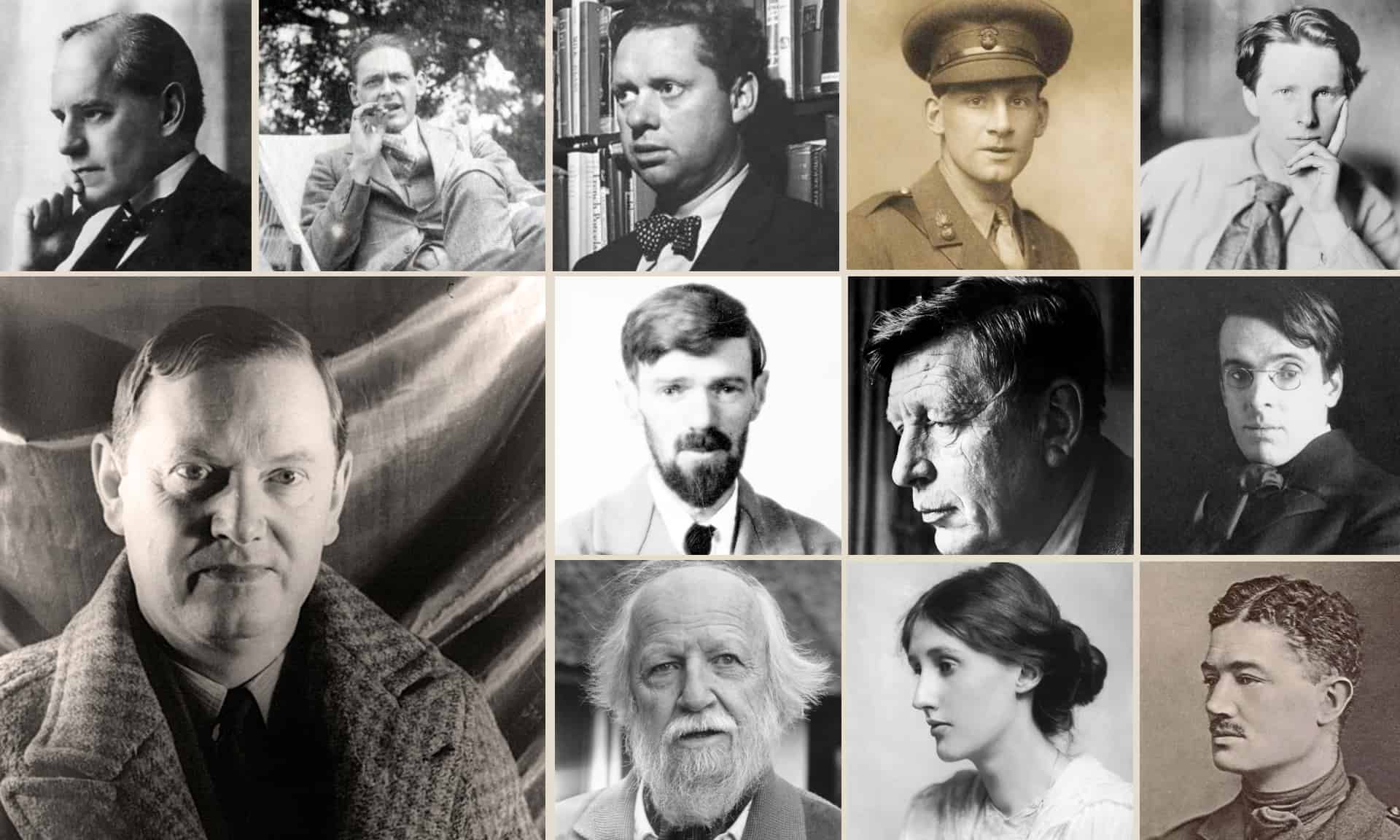

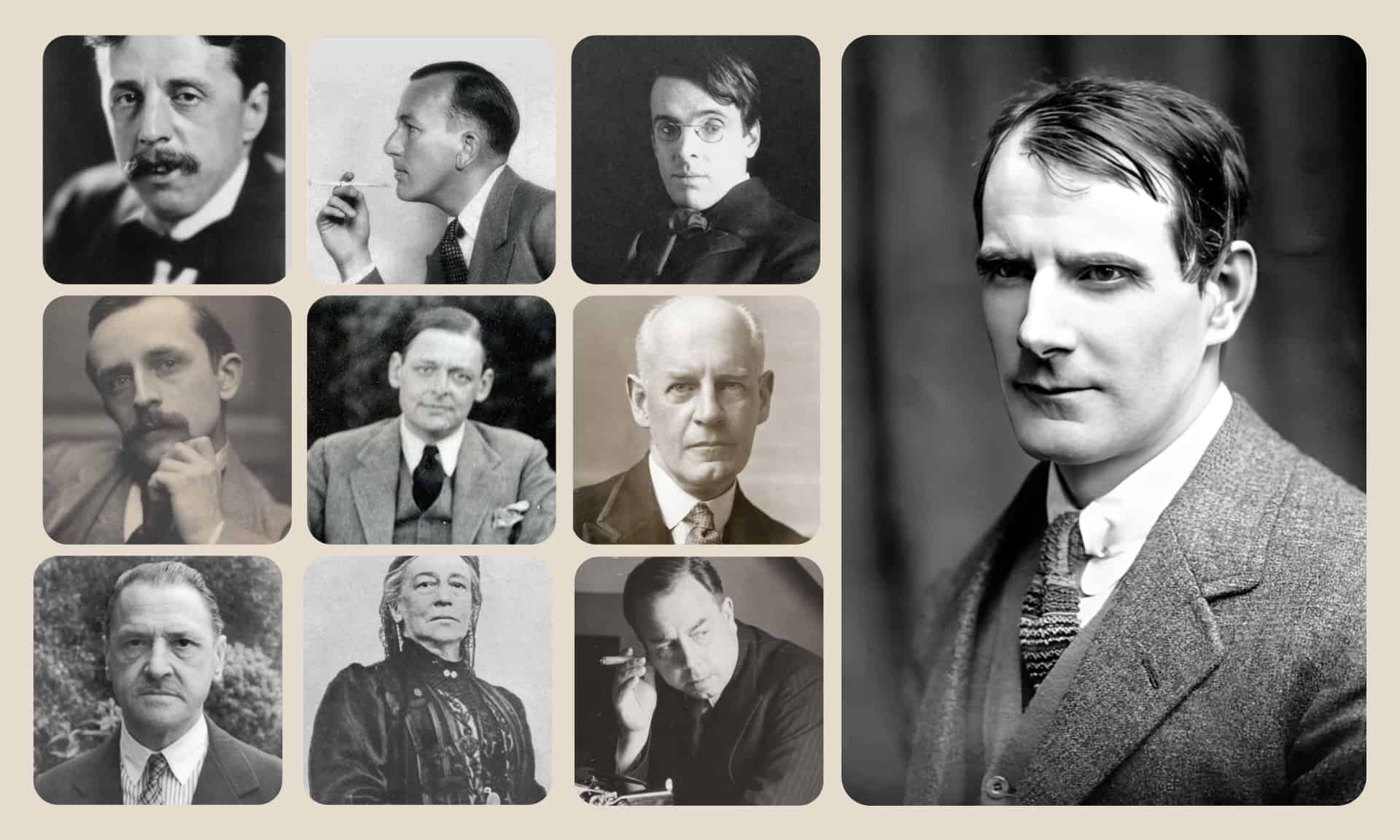

The most representative writers of this period belonged to the Irish Literary Theatre, and included W.B. Yeats, Lady Augusta Gregory and Sean O’Casey. They had their plays performed in the Abbey Theatre, which eventually became the fulcrum of the Irish acting tradition.

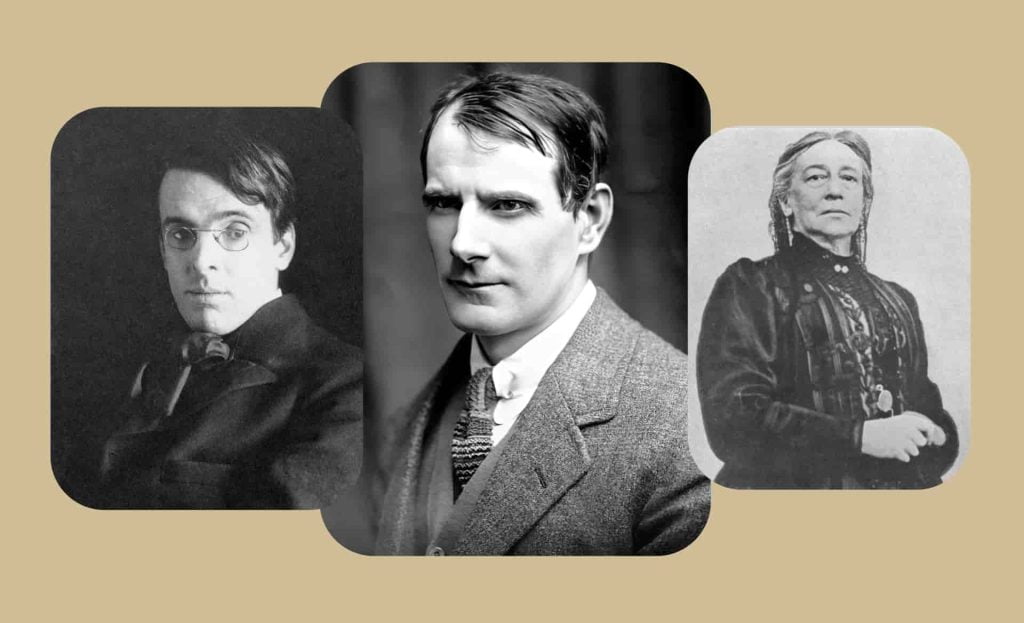

The Irish Literary Theatre was founded in Dublin, Ireland, in 1899. It proposed to give performances in Dublin of Irish plays by Irish authors. From left to right, W.B. Yeats, Sean O’Casey and Lady Augusta Gregory.

The literary career of Sean O’Casey commenced in 1923 with his involvement in the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. By that date he had written four plays: The Frost in the Flower, The Harvest Festival, The Crimson and the Tri-Colour and The Shadow of a Gunman.

The last of these plays proved to be a great success and received praise also by Yeats and Lady Gregory, who ran the theatre. Produced in 1923, it was accepted by the Abbey Theatre immediately, without any revision of the text.

It portrayed the devastating situation in Ireland, the problems of Irish independence and the psychological analysis of Seamus Shields, who pretended to be a daring, dangerous hero. In reality Shields was weak and cowardly. His words described the Irish condition thus:

The country is gone mad. Instead of counting their beads now they're countin’ bullets; their Hail Marys and Paternosters are burstin' bombs - burstin' bombs, an’ the rattle of machine guns; petrol is their holy water; their mass is a burnin' buildin'; their De Profundis is "The Soldier's Song”, an' their creed is, I believe in the gun almighty, maker of heaven an' earth - an' it's all for 'the glory of God an' the honour o’ Ireland.

Juno and the Paycock (1924) and The Plough and the Stars (1926) followed and today are considered his most popular plays, with the latter often regarded as his masterpiece.

Juno and the Paycock

Set in 1922 during the Civil War between Irish republicans and supporters of the Free State settlement, Juno and the Paycock not only addresses political issues surrounding the Irish question, but also focuses on the poverty and slums of Irish life.

Sara Allgood and Kathleen O’Regan in Juno and the Paycock (1929) © Wardour Films

The literary critic Herbert Goldstone believed that this play could be ‘underrated’ or ‘overrated’. He wrote in his, In Search of Community:

“We can all too easily both underrate and overrate Juno and the Paycock, the brilliantly amusing but sometimes heart-rending portrayal of the disintegration of a Dublin tenement family, the Boyles. We can underrate the play if we merely think of it as a lively, free-wheeling comedy that suddenly takes a tragic turn at the end. While in some respects the tragedy is forced and sudden, the comedy remains an integral part of Casey’s vision in which folly, selfishness, and moral chaos have grim, tragic consequences. On the other hand, we overrate the play if we assert that its affirmation of responsibility and elemental family love, embodied in Mrs Boyle (Juno), is as sustained or powerful as the irresponsibility and selfishness embodied in Boyle himself (the paycock).”

The Plough and the Stars, which was set during November 1915 and during the 1916 Easter Rising, also went beyond the political issues, focusing on religion, sex and patriotism.

The story did not follow the parameters of the staunch nationalists who saw Ireland as flawless. The anti-heroic interpretation of life in that period made the play extremely unpopular in his days.

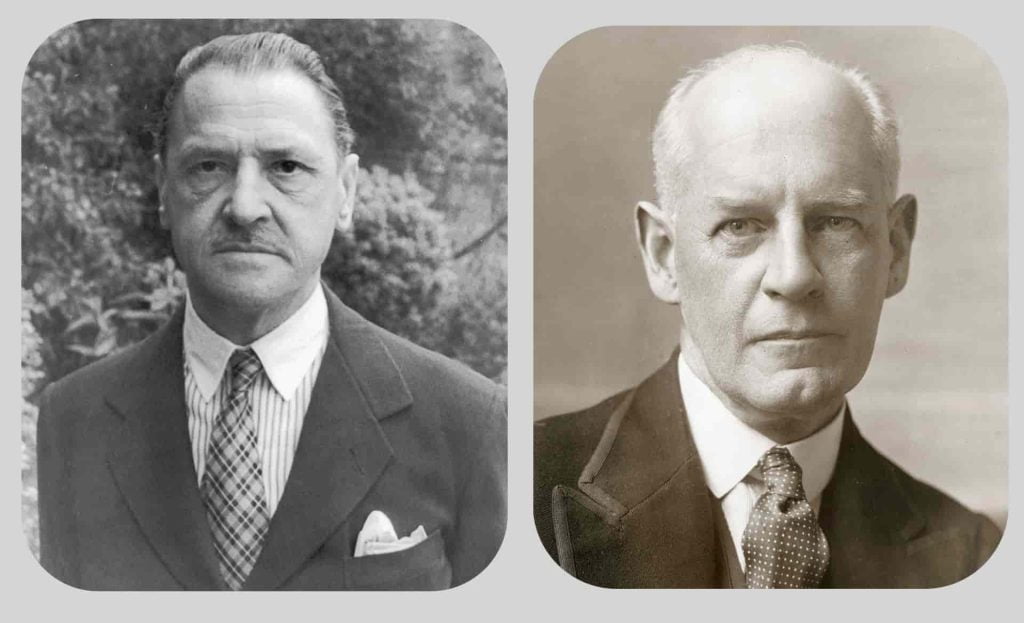

Right William Somerset Maugham, left John Galsworthy.

William Somerset Maugham and John Galsworthy as the writers of Of Human Bondage and The Forsythe Saga, were also very successful playwrights. Their works did not show any significant forms of experimentation or innovation, but nevertheless they excelled respectively in wit, satire and structural technique, and realistic social content.

Maugham’s The Circle (1919), The Constant Wife (1926) and The Breadwinner (1930) were perfect examples of his masterful use of language and wit, while Galsworthy’s The Silver Box (1906), The Skin Game (1920) and Escape (1926) reflected the playwright’s social awareness and acute perception.

Noel Coward also reached the heights of popularity during this period with his high-society comedies like Fallen Angels and Hay Fever, both produced in 1925.

Other two successful playwrights of the early 20th century were Arnold Bennett, who was also a typical realist novelist, and John Boynton Priestley, who reverted to the theatre with Dangerous Corner (1932) after achieving fame as a novelist. A particular type of Drama which could be termed as poetic drama or verse drama was also quite popular at the time.

The main exponents of this trend were T.S. Eliot, who in 1935 wrote Murder in the Cathedral; Christopher Fry, who wrote The Boy with a Cart in 1938, and A Phoenix Too Frequent in 1948; and W.H. Auden, who wrote in collaboration with Christopher Isherwood, The Dog Beneath the Skin, in 1935, The Ascent of F.6, in 1936 and On the Frontier, in 1938.

T.S. Eliot

Eliot in 1923 by Lady Ottoline Morrell © Open source

T.S. Eliot was definitely the most important of the poetic playwrights. He was already an established poet by the time he wrote Murder in the Cathedral. His Prufrock and Other Observations, published in 1917, and The Waste Land, published in 1922, won him not only respect as a major poet of the times, but also recognition as one of the most influential intellectuals of world literature.

Verse drama, which has its roots in the Renaissance period, was exploited to perfection by Eliot. In The Use of Poetry (1933), Eliot wrote that “the ideal medium for poetry […] is the theatre”, and by 1936 he concluded that poetry was “the natural and complete medium for the drama.” His theatre works were symptomatic of his theory.

The Rock (1934) blended eight different types of verse, varying from free verse to profound lyricism.

Among his other plays, like The Family Reunion (1939), The Cocktail Party (1950), The Confidential Clerk (1954) and The Elder Statesman (1959), Murder in the Cathedral was the most successful.

Murder in the Cathedral

Eliot wrote this play with the idea of the versification of Everyman, the 15th century morality play. He wrote it for the Canterbury Festival of June 1935.

The story is about the life of Thomas à Becket whose martyrdom in Canterbury was a very sensitive issue for the English.

Screenshot of Murder in the Cathedral (1951), directed by George Hoellering. Watch the full film on YouTube.

Henry ll was the cause of Becket’s assassination, which took place in Canterbury cathedral on December 29th 1170. The play is not only dramatic in its content but also in its structure.

The dramatic poetry is highly effective and the metrical form is very similar to the alliterative verse of Middle English. One of the best qualities of Murder in the Cathedral is the blending of highly poetic and dramatic speech with realistic everyday expressions.

Grover Smith, gives a perfect account of the essence of Eliot’s play in his T.S. Eliot’s Poetry and Plays, in which he portrays the intimate development of the character rather than the external plot that surrounds him.

“The play, though certainly taking its theme from the murder of St. Thomas à Becket in 1170, is not about “murder in the cathedral” but about the spiritual state of a martyr facing death, the spiritual education of the poor women who are witnesses to his sacrifice, and the wilful’ opposition of secular to eternal power [..] It is true that the historical personality of Becket gave the foundation to the plot. Eliot took a good deal of care to make the historical actions accord with the most trustworthy accounts of Becket’s contemporaries, but, since the play concerns rather what happens through the man than what happens to him, such details are largely incidental - as is all the action properly so called - to verbal expressions of various attitudes.”

Apart from the very popular Edwardian Plays, the Irish Literary Theatre, the handful of popular playwrights of the 1920s and 1930s, and the poetic playwrights championed by T.S. Eliot; British theatre had to wait for the post-World War Two period to witness true revolution and experimentation with the movements of Angry Young Men and the Theatre of the Absurd.