Chapter 1: Transcending the Moon, a Democratic Encounter

The first chapter will take you on a journey to discover a utopia where war is abolished and where facts are sacred. But the encounter will raise more questions than answers, as it challenges our understanding of war, humanity, and the future of our world.

In this story, we postulate an interview with the representative of a more advanced civilisation; and within this setting, novel visions are juxtaposed to some of our pressing problems. Learn more.

I could scarcely believe that I was about to embark on such a venture. The prospect of meeting an otherworldly being – a genuine extraterrestrial – was almost too fantastic to contemplate. And not just any alien, mind you, but the Dengilaun ambassador to our very own Moon!

As the engines of our vessel came to life, signalling the commencement of our journey, I found myself overcome with a heady mix of excitement and nerves. This, I knew, would be a trip unlike any other, and I was determined to make the most of it. As I gazed out at the endless expanse of space through the window of the craft, my heart pounded. The idea of leaving Earth behind and venturing into the cold and darkness of the cosmos, was both exhilarating and intimidating. I tried to focus on my notes and questions for the interview, but my mind kept drifting to the sights and experiences that awaited me. I wondered what the Dengilaun ambassador might be like and what their perspective on the universe would be.

On the momentous day when we received the video message from the Dengilauns, I knew it was a moment that would be remembered for centuries to come. The message itself was unlike anything we had ever seen, transmitted through a form of holographic technology that seemed to defy all known laws of physics. As soon as we realised that the message was not of earthly origin, a frenzy of activity erupted. Governments and scientific institutions scrambled to decipher the message and find a way to communicate back with these mysterious beings.

The Dengilauns had made it clear that they wished to establish friendly relations with humanity, and had even invited us to a conference on the moon, where they hoped to establish a permanent embassy. As a journalist, I knew I had to be a part of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I applied to join the United Nations’ delegation and, to my great surprise and delight, was selected as chief press officer. Joining us on this historic journey were the Secretary-General, William Thompson and elected President of the United States of Aurelia, Madison Davis, who was the leader of the wealthiest and mightiest federation on planet earth.

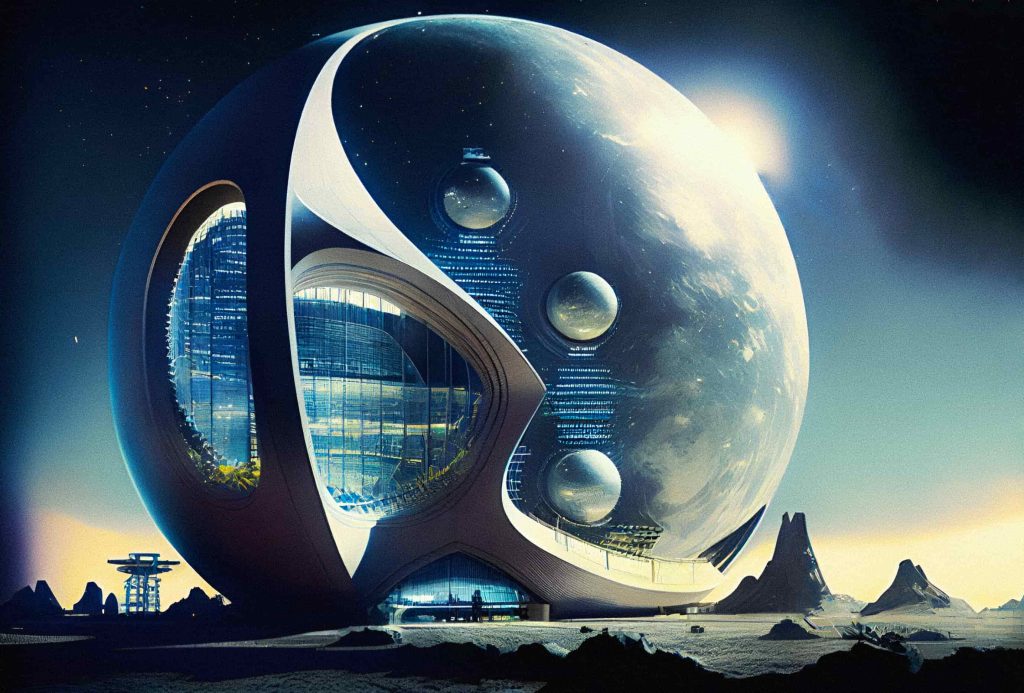

The Dengilaun embassy on the Moon. Photo: UN-aligned prompted via Midjourney

I stepped out of the lunar rover and onto the surface of the moon, my heart racing with excitement and trepidation. My eyes were immediately drawn to the Dengilaun embassy, a towering structure of gleaming metal and glass that seemed almost like a snow globe, filled with intricate structures and patterns. I took a deep breath and tried to calm my nerves as the doors opened, and we found ourselves face to face with the Dengilauns. They were nothing like I had imagined them to be. They were creatures of extraordinary poise and dignified bearing, their speech a veritable symphony of words unlike any that I had hitherto encountered.

“Emoclew, humans”, the ambassador said, their voice a harmonious yet gravelly timbre as they stood before a group of Dengilauns. “It is good to meet you. Please, do come in.”

Astonished by their command of the English language, we followed them inside. We were led into the ambassador’s hall, a spacious and well-lit room with tall windows that looked out onto the stark and barren landscape of the moon. The walls were adorned with paintings and large sculptures depicting scenes from Dengilaun history. The ambassador invited us to take a seat at the round table, pointing to the hovering cushions on the floor. The ambassador’s gaze flickered between us as we each introduced ourselves; their demeanour composed and serene.

The Secretary-General thanked the ambassador for the invitation. “It is good to meet you ambassador. We hope this conference will be the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship between humanity and Dengilauns.”

The ambassador nodded solemnly. “I share that hope, Mr. Thompson. We come to you in peace, seeking to build friendship and mutual understanding between our worlds.” They then turned to our delegation: “I know you must have many questions, so please do not hesitate to ask me anything.”

Mr. Thompson seized the opportunity to inquire about the reason for the Dengilauns’ journey to our solar system. “Please do tell us, Ambassador, who are the Dengilaun and what secrets of the cosmos do they possess? What prompted your decision to visit us?”

The Dengilaun ambassador let out a heavy sigh as they began to speak of their long journey to our solar system. “We hail from the galaxy of Dengilaun Prime, where equality, justice, and the common good are held in high regard. Our system is continuously evolving, a utopian democracy in which all members have a say in decisions that shape every aspect of our society. We have no politics and no politicians; we have an economy that has ethics at its heart and a planet that strives towards improvement. Our utopian thinking is the beating heart of our society, the driving force behind our many millennia of peace and prosperity.”

“But alas, despite our advanced understanding of the cosmos, we were forced to leave our planets behind as a massive black hole engulfed our galaxy and forced us to evacuate. While we left much behind, we are determined to rebuild and reclaim our place amongst the stars. We are not immune to the forces of nature, but we are as adaptable as we should be. It is our determination and resilience that brought us to your solar system and that has led us to choose Mars as our new home.”

The Dengilaun’s tale left us deeply astonished and fascinated. As we processed their words, the Secretary-General replied, “Ambassador, your story moves us deeply. Though Earth may seem insignificant, compared to your civilisation, it too is a world on the rise. We have a robust system of representative democracy and a global economy that is constantly improving. We are making great strides in science and technology and we are always working to address issues of inequality and injustice.”

As the Secretary-General was bragging on, I couldn’t help but reflect on the current state of affairs on Earth. Of course, Mr. Thompson was right to paint a rosy picture of earth, that was after all his job. However, there were details Mr. Thompson could not comfortably share.

Climate change, which we had been warned about for centuries, had caused food shortages, widespread famine and mass migration resulting in the deaths of more than half a billion people. Despite this grave threat to our very existence, the United Nations and its members’ response has always been slow and inadequate, as everyone constantly engaged in delays and pointless negotiations.

This year, as I participated in COP 127, I couldn’t help but wonder how many lives might have been saved if we had just followed the science and acted more decisively sooner. It is a question that is impossible to answer, but it is also a question that is far from academic. I wondered whether our current system of representative democracy, with its complex and often ineffective decision-making processes, is truly the most effective way to address such challenges.

As I listened to the ambassador describe the utopian democracy of their homeland, I was struck by the stark contrast with the democracy on my own planet, a system which has bred turmoil, inequality, climate change, poverty and war. I couldn’t help but wonder: could a different system be more effective in addressing these complex issues? As I listened to Mr. Thompson speak, I jotted down a few questions on my notepad that I hoped to ask later.

President Madison Davis, noticing the ambassador’s nod to the Secretary-General, confidently posed a question of his own: “Ambassador, I must confess my curiosity about your system of government. You speak of a utopian democracy, yet you mention the absence of politicians or leaders. How can this be reconciled? On earth, we rely on politics and representative democracy to give voice to the people and address their needs.”

“I see your point, President Davis, but allow me to express my scepticism - how can a system that relies on the selection of leaders through a politicised process truly represent the will of the people? Are you not concerned that the interests of powerful groups would take precedence over the needs of your population?”, asked the Dengilaun ambassador.

“There is a possibility of that happening,” President Davis admitted. He furrowed his brow in thought. “But our system is designed with checks and balances and an independent judiciary to prevent it. In our democracy, people can choose to dispose of their leaders if they are not satisfied with their performance. This ensures that the needs of the people are met eventually, even if the system is not perfect.”

“I see,” said the Dengilaun ambassador, his voice tinged with understanding. “The absence of politicians in our utopian society is not a result of disdain, but rather a recognition of the inherent flaws in such systems. Corruption and the unequal distribution of power are but a few of the maladies we have observed in the political structures of other civilisations. Our society strives to avoid such pitfalls.”

“The Dengilauns have learned that we cannot rely on a few leaders to make decisions for the whole of society, for when there is disagreement about who should lead, the process can become more about justifying policies than finding solutions. So, we rely on the collective wisdom of our citizens through direct democracy. This allows us to decide on policy initiatives without intermediaries, which fosters a sense of political engagement and renders each vote invaluable.”

“However, even the most virtuous of us can sometimes err in their judgement. That is why we constantly review a manifesto of ethical norms, a beacon to guide our decision-making and ensure that our actions uphold the values of liberty, fraternity and equality, preserving the delicate balance of our world and avoiding harm at all cost.”

President Madison Davis replied: “That is certainly an intriguing alternative, ambassador. But I would argue that our representative democracy, while not without its flaws, is the better system as it ensures the long-term stability and prosperity of our society. As a great leader on earth once said: ‘democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others’.”

As President Davis recycled these ancient words of Churchill, I couldn’t help but feel a surge of outrage at the lack of understanding displayed by the president. How can we accept the idea that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others, while at the same time striving for a better system? Are we truly striving for a better alternative, or are we resigned to accepting flawed systems?

President Madison Davis, the democratically elected President of the United States of Aurelia. Photo: UN-aligned, prompted via Midjourney

President Davis readjusted himself on his cushion, his arms crossed over his chest as he continued. “Ambassador, I must know - how do you possibly manage to guide your civilisation through crises like the mass migration across the galaxy? It seems absurd to me that you would involve every single member of your society in such important decisions. Won’t this take forever? Do you not have any leaders to turn to in times of crisis? Enlighten me.”

“That is a good question, President”, said the ambassador, who went on to explain: “We use citizen juries to address significant decisions. These are small groups of randomly chosen individuals who are given access to all the relevant facts and science and are able to discuss and decide on the issue at hand. We have found this to be the most effective way to consider a diverse range of perspectives during urgent matters.”

“As for leadership, we are not opposed to it, but leadership in the Dengilaun society is more fluid and dynamic, with individuals stepping into leadership roles as needed and stepping back once their task has been completed.”

“Jurors you say?”, said Mr. Davis with an unusually loud tone, we are too familiar with those, and know better not to trust them for important decisions like that. We know that the process of appointing them does carry serious faults. How do you, for example, ensure that a diverse range of perspectives are considered in these citizen juries?" President Davis enquired.

“To ensure that our juries are representative and diverse, we have implemented a variety of measures.” The ambassador continued: “We have made efforts to make our recruitment practices more inclusive and have worked to ensure that the jury selection process is reflective of our community. In addition, jurors are provided with comprehensive education and information about the issues at hand, as well as training on how to recognise and mitigate their own biases.”

“We encourage jurors to use techniques like deliberation prompts to think critically and consider different viewpoints. By doing so, we aim to ensure that our juries are able to make informed and fair decisions that take into account a variety of perspectives.”

“And how do you ensure that facts do not become politicised?”, asked President Davis.

The ambassador paused, a thoughtful look on their face. “For the Dengilauns facts are sacred and truth is constant, alternative facts are nothing but falsehood.”

The ambassador’s words were like a breath of fresh air. I was struck by the thought and care that went into their democratic process. The idea of citizen juries, where small groups of randomly chosen individuals came together to discuss and make decisions on critical issues, was particularly interesting to me. It seemed like a more efficient and effective way of reaching a consensus than traditional parliamentary systems.

It was now my turn to put my questions to the otherworldly being.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with me, Ambassador, I said, trying to contain my excitement. Earlier, you mentioned that one of your society’s guiding principles was to avoid causing harm to others at all cost. On Earth, we too strive to create a society free from war.

However, despite the efforts of multinational organisations and our international laws, wars continue to devastate communities and claim the lives of countless innocents. From the bloody trenches of World War I to ongoing conflicts, which has resulted in a record-breaking number of refugees, the history of Earth is marked by a seemingly vicious cycle of violence and destruction.

Some people believe that we have a natural tendency towards violence and aggression. Can you tell me more about how your utopian society addresses this issue?

The ambassador paused, their fingers steepled in front of their face as they considered my question. “I am sorry to hear about these dreadful conditions on earth. Our path to a society without war was not an easy one. Like your society, we too grappled with the devastating repercussions of war. However, we made the conscious decision to prohibit war and abolish the concept of ‘soldier’, acknowledging them as destructive forces that cause immense suffering and pain for all involved.”

“We did not stop there. To further strengthen our efforts to maintain peace and justice, we established an international police force that was always better resourced and equipped than local groups in the Dengilaun society. This police force is supervised by a multinational ethical body and structured to withstand abuse, as a safeguard against attempts to undermine, exploit or hijack the system.

“By taking these steps, we have been able to create a society that is free from the horrors of war and dedicated to the well-being and prosperity of all its members.”

I could not believe what I was hearing. Surely, the solution of abolishing war cannot be as simplistic as making it illegal…

Then it dawned on me, humanity has never truly been invested in ending war. Throughout history, from the religious and ideological battles of old to modern conflicts over resources and influence, we have consistently sought to rationalise and legitimise the use of force and violence as a means of resolving conflicts. Even our so-called “defensive” measures are often excessively aggressive, leaving one to question the true nature of our actions.

Despite the devastating consequences of war, we continue to see it as a necessary evil, something that is inevitable and even necessary in ‘certain circumstances’. This obsession with justifying war has had a profound impact on our history and our world, shaping the way we think about conflict and violence and leaving a lasting legacy of suffering and destruction.

In contrast, the Dengilaun society has succeeded where the United Nations has failed. Rather than merely trying to regulate the use of force in warfare, it has made the bold decision to eliminate war altogether. Recognising the inherent cruelty and devastation of armed conflict.

I took more notes as the ambassador spoke. That is certainly very interesting, Ambassador, I said, my pen scratching across the page.

How about defence? How does your society defend itself against threats or aggression, given that you do not have a military or engage in war?”

“As a society, we firmly reject the notion of engaging in war and the use of military force as it is a destructive practice that causes suffering and hardship for all involved,” the Ambassador responded. “Instead, we have a defence force that is not only trained and equipped to protect our society and its members, but also guided by a strong ethical code to ensure they act in the best interest of peace and non-violent conflict resolution.

“In our eyes, there can be no justification for war, be it defensive or otherwise. We hold the pursuit of peace in the highest regard, recognising that many conflicts arise from the desire for power and resources. To mitigate this, we have implemented a system of resource sharing and cooperation, guaranteeing all members of our society access to life’s essentials.

“Furthermore, our society does not believe in physical barriers or borders between communities, promoting the free flow of people, ideas, and resources. This inclusivity and openness has led to a harmonious and prosperous society.

“We are always on the lookout for non-violent ways to handle conflicts and protect our society. We strive to cultivate a culture of peace within our communities and societies by promoting understanding, compassion and cooperation. By doing so, we believe that we can prevent conflicts from escalating into violence and create a society that is just and harmonious for all.”

As the ambassador spoke, I couldn’t help but be struck by the passion in their voice. It was clear that they truly believed in the principles they were describing, and that their society had created something truly unique and special. I jotted down notes feverishly, trying to capture every word and detail of the utopian society the ambassador was describing.

From Plato to modern utopian thinkers, the idea of a world completely devoid of war has been an elusive concept, with many positing that war fought for a just cause and conducted in a just manner can be justified. Even in the acclaimed Utopia by Thomas More, society is not depicted as completely pacifist. Humanity just does not seem capable of imagining a world without war.

The Dengilaun base on Mars. Photo: UN-aligned, prompted via Midjourney

The conference was coming to an end and I only had one question left. I had been giving it much thought. I looked up at the ambassador with curiosity. “Your society has achieved a level of peace and harmony that is truly admirable. What guidance would you offer to other societies, such as ours on Earth, that are struggling to create a more just and harmonious world?”

“We recognise the importance of being vigilant against the usurping of democracy by the existing social orders,” the ambassador said. “That is why we place a strong emphasis on the development of a critical utopian sensibility, which involves being attuned to the ways in which our political and social institutions limit our imagination and prevent us from realising alternative futures.”

“One thing that I would recommend is to constantly question and challenge the status quo,” the ambassador said. “Don’t be afraid to envision and work towards alternative futures. And be attuned to the ways in which your political and social institutions may be limiting your imagination and preventing you from realising those alternative futures.

As the day’s conference came to a close, I couldn’t help but wonder if a utopian society like the Dengilauns’ was really possible on Earth. While it seemed like a distant dream, the ambassador’s words had sparked a flame of hope within me. Could we really create a world free from conflict and dedicated to the well-being of all its citizens? It would be a difficult journey, but certainly one that was worth striving for.

We left the ambassador’s hall and stepped outside into the large garden of the embassy. I turned to the Secretary-General and the President, eager to hear their thoughts on the conference. “What did you think of the conference?” I asked.

“It was certainly an eye-opening experience,” the Secretary-General said, a thoughtful expression on his face. “The Dengilauns have much to teach us about the importance of peace and non-violent conflict resolution.”

“I agree,” the President said. “Their approach to governance and defence is certainly worth considering. But we must also remember the strengths of our own system and the progress we have made on Earth.”

Upon our return to the main building, I was eager to see what the following days would bring. It would be a challenging journey, no doubt, but one I was determined to undertake. As I retired to my room at the embassy, which was kindly provided to me during my stay, I resolved to absorb as much knowledge as possible and bring back new ideas and solutions to our world on Earth.

My reporting of the second day of the conference will be published next month in February 2023. Make sure to subscribe to The Gordian Magazine, so you won’t miss it.

Do you have any questions that you would like me to ask the ambassador? Let me know!