The Montreux Declaration: An Alternative Vision for World Peace

The Montreux Declaration presents a coherent alternative to the UN's design flaws for achieving genuine world peace, argues Lukas Pfluger.

After two devastating world wars, the prospect of “universal death” was on everyone’s mind. It was time for global institutions to ensure genuine world peace. The United Nations was formed “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war”.

Its mission statement reflected the deep desire of war-ravaged humankind to put an end to international violence once and for all. Yet even before the foundation of the UN, activists and scholars had warned about the UN Charter’s design flaws. The criticism of the UN structure has lost nothing in relevance to this day.

Just like the League of Nations, the United Nations was not equipped with the tools to fulfil its purpose. Crucial decisions were hampered by the veto power of nuclear-armed superpowers, representation did not reflect the will or even number of the population of a state, and there was no independent budget or police force to act and enforce world law.

Inspired by bestsellers such as Clarence Streit’s Union Now, Emery Reves’ Anatomy of Peace, and Wendell L. Willkie’s One World, young people across the world formulated a coherent alternative to the status quo: world federalism.

The Montreux declaration

WWII saw many world federalist organisations spring up around the world, attracting hundreds of thousands of members. To accomplish anything, the need for unity amongst the activists became self-evident.

It was at this point in 1947 that the World Movement for World Federal Government held its first international congress in Switzerland. On the banks of Lake Geneva, it issued what would later be known as the Montreux Declaration.

Besides the weapons of mass destruction used in both world wars, the recent development of nuclear weapons raised the stakes of conflict to the unimaginable, the unacceptable. “We are convinced that mankind cannot survive another world conflict,” reads one of the first sentences of the declaration.

Far from picking a side in the ensuing ideological conflict that would later precipitate into the Cold War, the world federalists found the root of recurring wars and hardship in the existing system of absolute national sovereignty.

Unrestricted sovereignty leads to an international fight of all against all – a global anarchy. The solution: a global political system based on the principles of democracy, rule of law, and federalism.

“We world federalists are convinced that the establishment of a world federal government is the crucial problem of our time. Until it is solved, all other issues, whether national or international, will remain unsettled. It is not between free enterprise and planned economy, nor between capitalism and communism that the choice lies, but between federalism and power politics. Federalism alone can assure the survival of man.”

The world federalists put their finger on six issues that would hamper the UN’s work in the future.

1. Universal membership

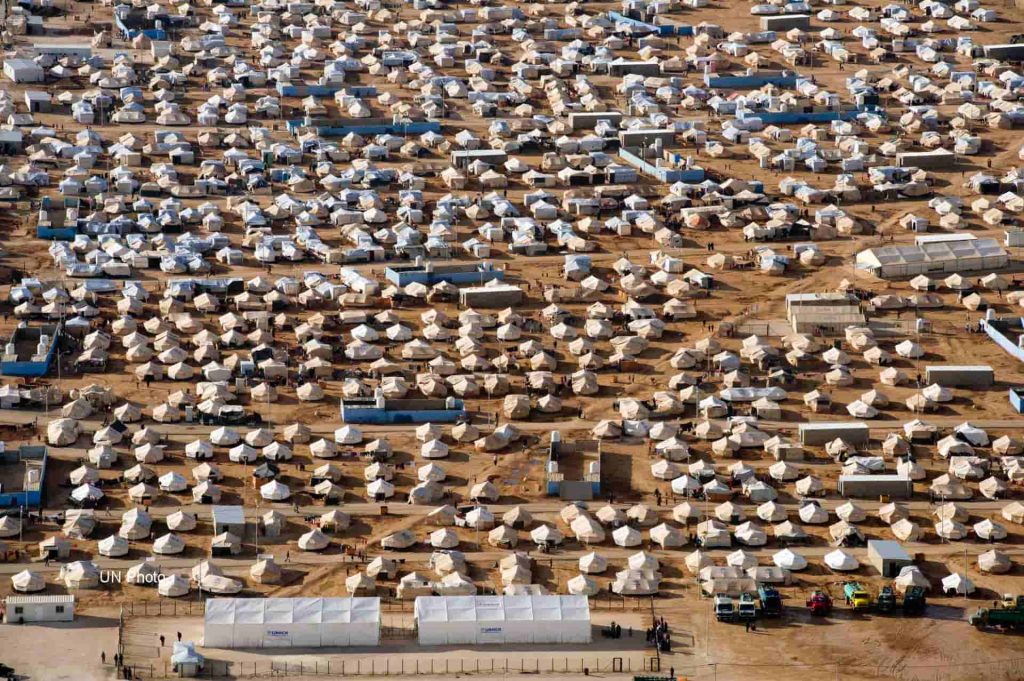

It is estimated that more than 10 million people in the world today are stateless. Photo United Nations Photo/Flickr

The world federal government must be open to all peoples and nations. Whereas the UN Charter limits itself to member states, the world population goes far beyond that. Citizens of undemocratic countries and those favouring opposition parties are not represented by the government representatives in New York or Geneva.

Stateless people, refugees, indigenous people, migrants, nomads, and many others usually do not have the recognition of the states they find themselves in.

Universal membership would mean that disenfranchised people around the world would finally get the political participation they, by virtue of being fellow humans, deserve.

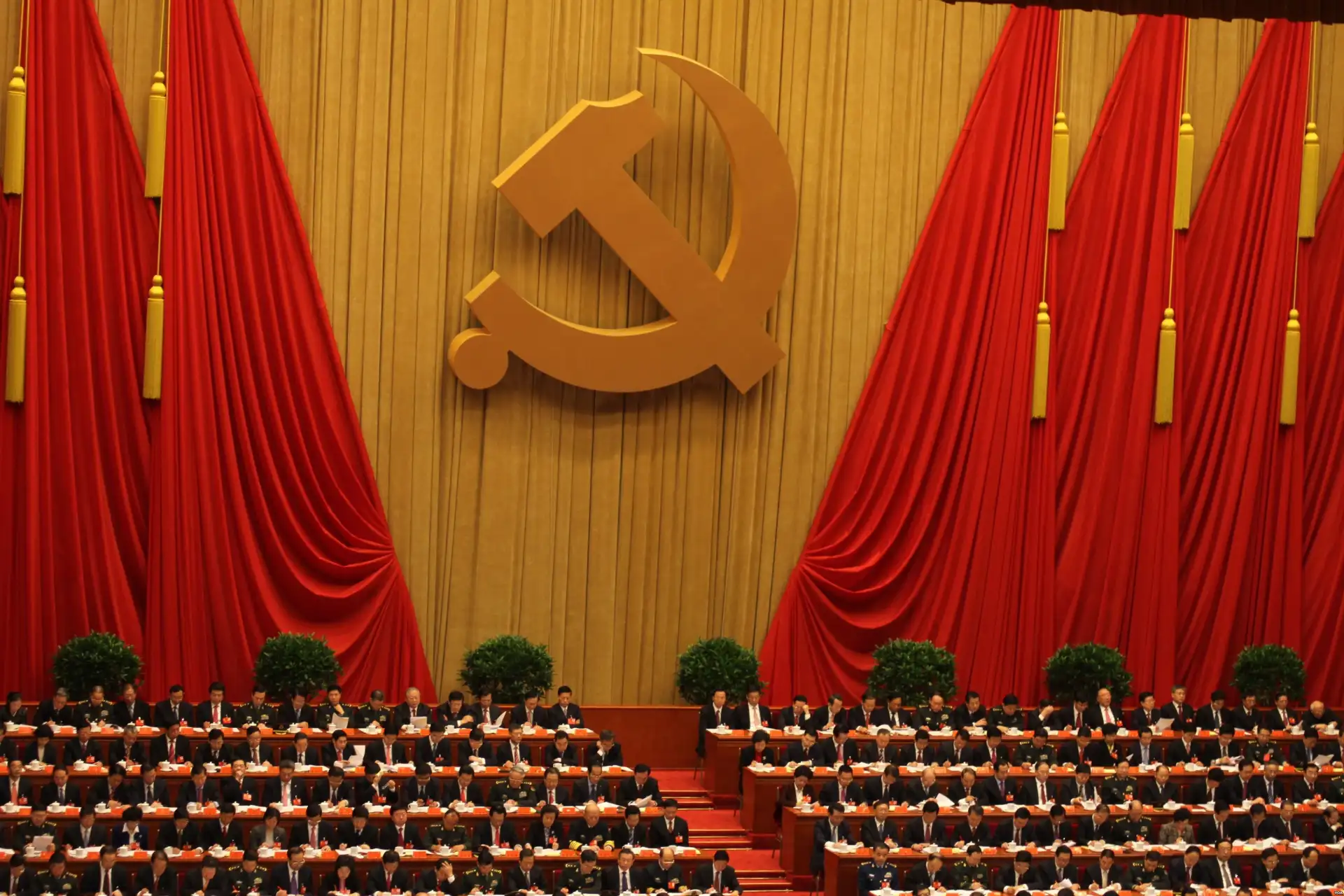

2. International government

Limitation of national sovereignty, and the transfer to the world federal government of such legislative, executive and judicial powers that relate to world affairs.

Healthy federalism rests on the principle of subsidiarity - handling issues at the lowest appropriate level. Some decisions are best taken by local or municipal administrations (e.g., urban planning), while others require larger cooperation on a regional (e.g., policing) or national level (e.g., minting currency).

By now we have learned that there are issues that even nations are too small and incapable to adequately address. Nations have been unable to stop greenhouse gas emissions in time to prevent unspeakable harm.

Some issues are inherently caused and exacerbated by the system of international rivalry: nations are unable to stop the cycle of violence originating from irredentism, imperialism, and impunity on the global scale.

These - and only these - are the competences that world federalists aim to transfer to a governmental level more suited to deal with them: global problems require global solutions.

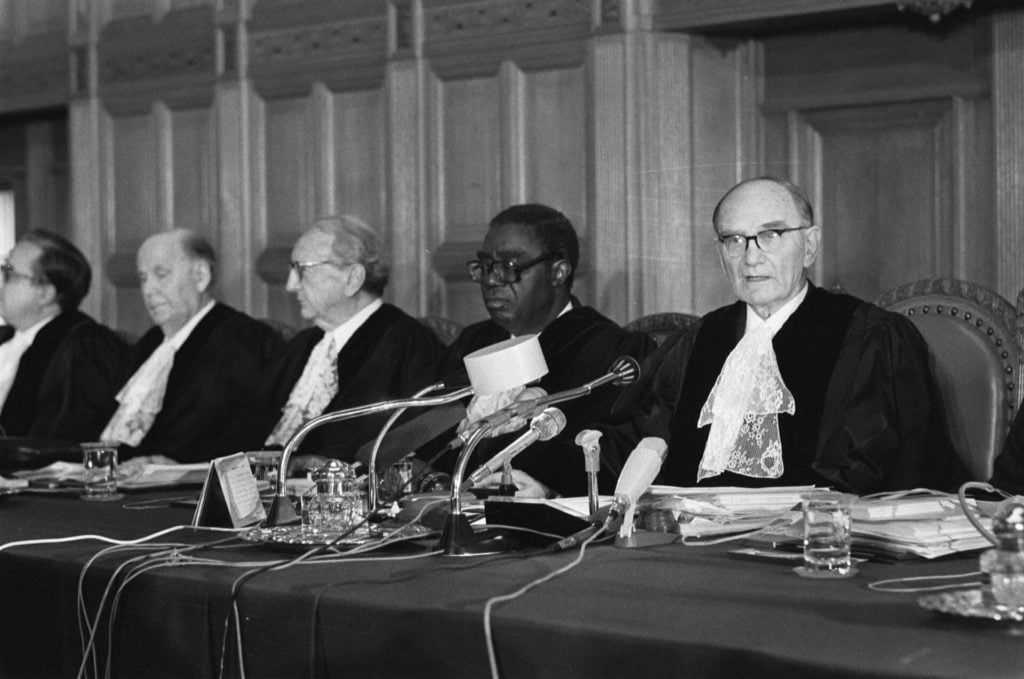

3. International law enforcement

Enforcement of world law directly on the individual whoever or wherever he may be, within the jurisdiction of the world federal government: guarantee of the rights of man and suppression of all attempts against the security of the federation.

The ICJ can only adjudicate when all the States involved in the case in question have accepted the court’s jurisdiction. This may be done in three ways.

Collective punishment is rightfully seen as archaic and inhumane. Yet out of necessity, we do still frequently engage in it even to this day. Economic sanctions are one of the few ways in which the world community can bring a rogue nation to its knees, to the detriment of the citizens already suffering under the regime.

Learn more: What is the difference between the ICJ and the ICC?

Far too often, sanctions do not reach their intended goal, but instead create a new breeding ground for vengeful nationalism, fuelling the regime the sanctions originally targeted.

Universal membership of people, rather than nations, also means that individuals have standing in a global court of law. Rather than, for example, broad sanctions on Iran, the individual people responsible for the oppression of women there could be tried in a global court of law.

Russian war criminals could be held accountable for their atrocities in Ukraine. Their American counterparts could not torture any more with impunity. Multinational corporations could be sued for environmental destruction or tax evasion.

“Law Not War” had become the guiding principle of Benjamin Ferencz, chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials. The theme was even picked up by Dwight D. Eisenhower:

“The world no longer has a choice between force and law; if civilisation is to survive, it must choose the rule of law. There must be law, steadily invoked and respected by all nations, for without law, the world promises only such meager justice as the pity of the strong upon the weak.”

How is this world law to be invoked?

4. International defence force

Creation of supranational armed forces capable of guaranteeing the security of the world federal government and of its member states. Disarmament of member nations to the level of their internal policing requirements.

UN Peacekeepers, better known as Blue Helmets, operate under the direct mandate of the UN Security Council. Photo: United Nations Photo/Flickr

A recurring joke nowadays is that the UN is useless. The UN doubtlessly had successes: the eradication of smallpox and its contribution to ending world hunger, for instance. Yet when it comes to protecting people “from the scourge of war” and holding dictators accountable, the UN does unfortunately suffer from a lack of meaningful enforcement.

Enforcement is entirely in the hands of national governments. Yes, there are UN Peacekeepers. But relying on the willingness of national governments to equip, deploy and supervise them is dangerous for the people most relying on their help.

The Rwanda genocide should have served us as a wakeup call. The world needs a rapid reaction force that can actually be deployed to save lives, and that is accountable to a democratic world parliament.

In a political sphere that philosophers like Jürgen Habermas and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker described as “global domestic politics”, the need for weapons of mass destruction vanishes. The primary task of a world federal government would be to regulate and control the development and use of nuclear weapons and other technologies that have the potential for mass destruction, in order to ensure global security and stability.

5. Regulation of weapons

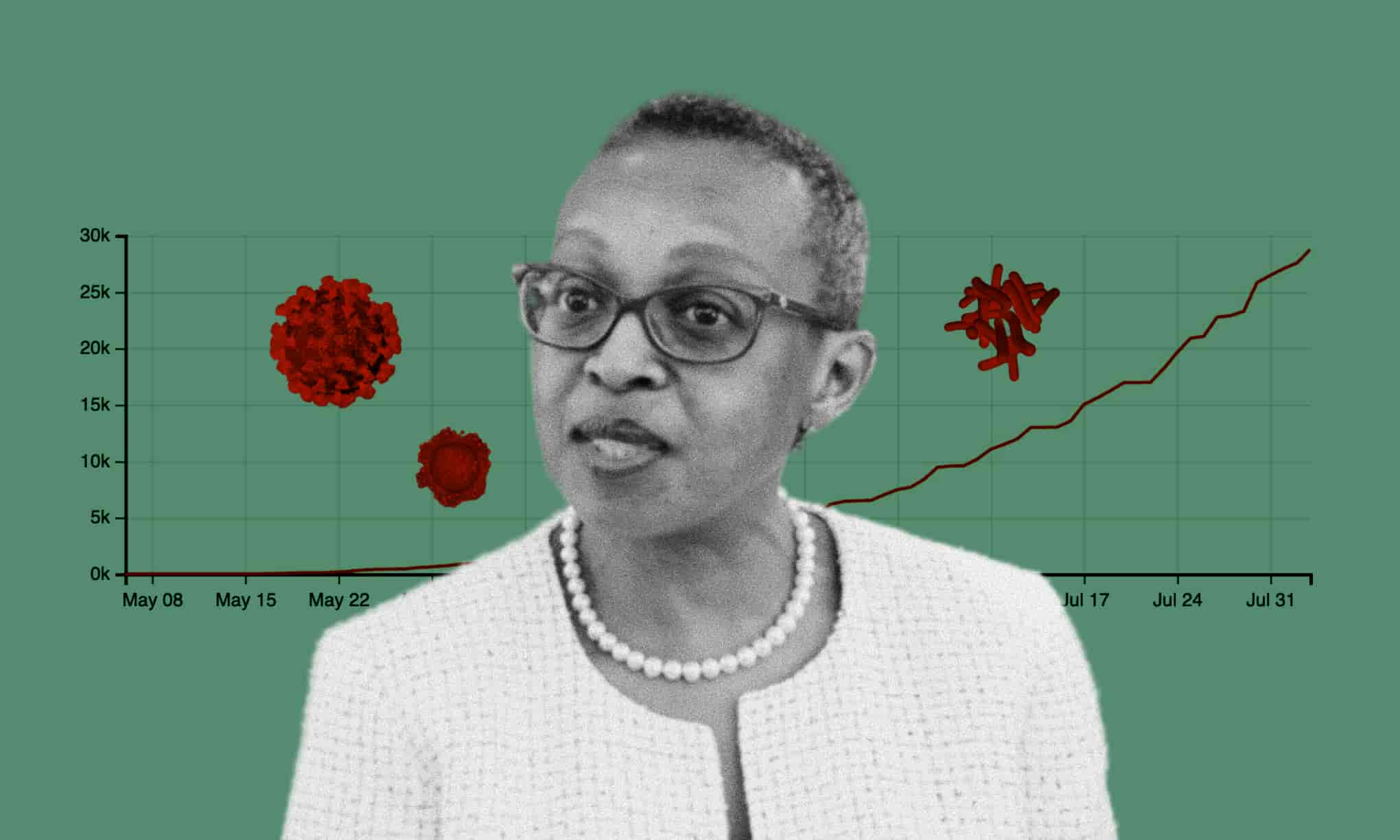

Any government costs money, and a global government would be no different. The UN and its diverse programmes are usually funded by member state contributions. The conditions of these contributions have caused problems and suspicions throughout history.

The claims of a bias of the World Health Organisation towards China or the United States is but one example of this. What a global government needs instead is the power to raise adequate revenues directly and independently of state taxes.

6. Maintaining world peace

Few people would disagree with the overarching goal - a world order based on peace and rule of law, rather than sheer force and tentative diplomacy. The more contentious question revolves around how to get there.

One possible way is unification at a continental level. The European Union, but also the United States or India serve as exemplary models for how political integration on an enormous scale can work. Maybe the World Federalist Movement (as the movement that drafted the Montreux Declaration would later be named) foresaw the Cold War and rising nationalism when they stressed:

"We consider that integration of activities at regional and functional levels is consistent with the true federal approach. The formation of regional federations – insofar as they do not become an end in themselves or run the risk of crystallising into blocs – can and should contribute to the effective functioning of federal government."

Another way is to demand a reform of the United Nations. After all, it already exists.

"The mobilisation of the peoples of the world to bring pressure on their governments and legislative assemblies to transform the United Nations Organisation into world federal government by increasing its authority and resources, and by amending its Charter."

The shortcomings of the UN Charter were well-known even at its inception. So well, in fact, that a provision for a comprehensive revision had been written into the Charter itself. Article 193 stipulates that:

(1) A General Conference of the Members of the United Nations for the purpose of reviewing the present Charter may be held at a date and place to be fixed by a two-thirds vote of the members of the General Assembly and by a vote of any nine members of the Security Council.

Notably, a single permanent Security Council member cannot veto such a Charter review. In case the article hadn’t been triggered by 1955, section (3) makes it even clearer:

(3) If such a conference has not been held before the tenth annual session of the General Assembly following the coming into force of the present Charter, the proposal to call such a conference shall be placed on the agenda of that session of the General Assembly, and the conference shall be held if so decided by a majority vote of the members of the General Assembly and by a vote of any seven members of the Security Council.

This section has become known as the San Francisco Promise. A review of the UN Charter could be a practical way to reform the United Nations from the ground up.

Promoting global unity and change

Beyond government and legal structures, any change must start in people’s minds. People themselves should be inspired to take part in drafting the constitution of a world they themselves want to live in.

Seventy-five years have passed since the Montreux Declaration was written. Not much has changed. The UN recognises the need for self-reform, especially in the face of threats of global scale. From the valid criticism of an often times weak UN, we must not fall prey to the nationalist narrative of discarding international organisations altogether.

Instead, we should work to improve them so that they are equipped to fulfil the task they are meant to do: save succeeding generations from the threat of war, protect human rights and promote social progress.

None of this is optional, and none of this is futuristic utopianism. The hardships and suffering of people, whether caused by war, hunger, poverty, climate change, diseases or abuse of power, are real and urgent.

“More than ever, time presses. And this time we must not fail.”