Preserving Peace and Heritage: Converting Woodrow Wilson's Vision into a UN World Park Service

Could Wilson's US National Park Service inspire a UN World Park Service to preserve ecological and historic sites, promote international cooperation, and appreciate cultural heritage?

Could Wilson’s vision for the US National Park Service inspire a UN World Park Service? This global agency, dedicated to preserving ecological and historic sites, could promote international cooperation, environmental conservation, and the collective appreciation of our cultural heritage.

Modern Internationalism with Wilsonian Idealism

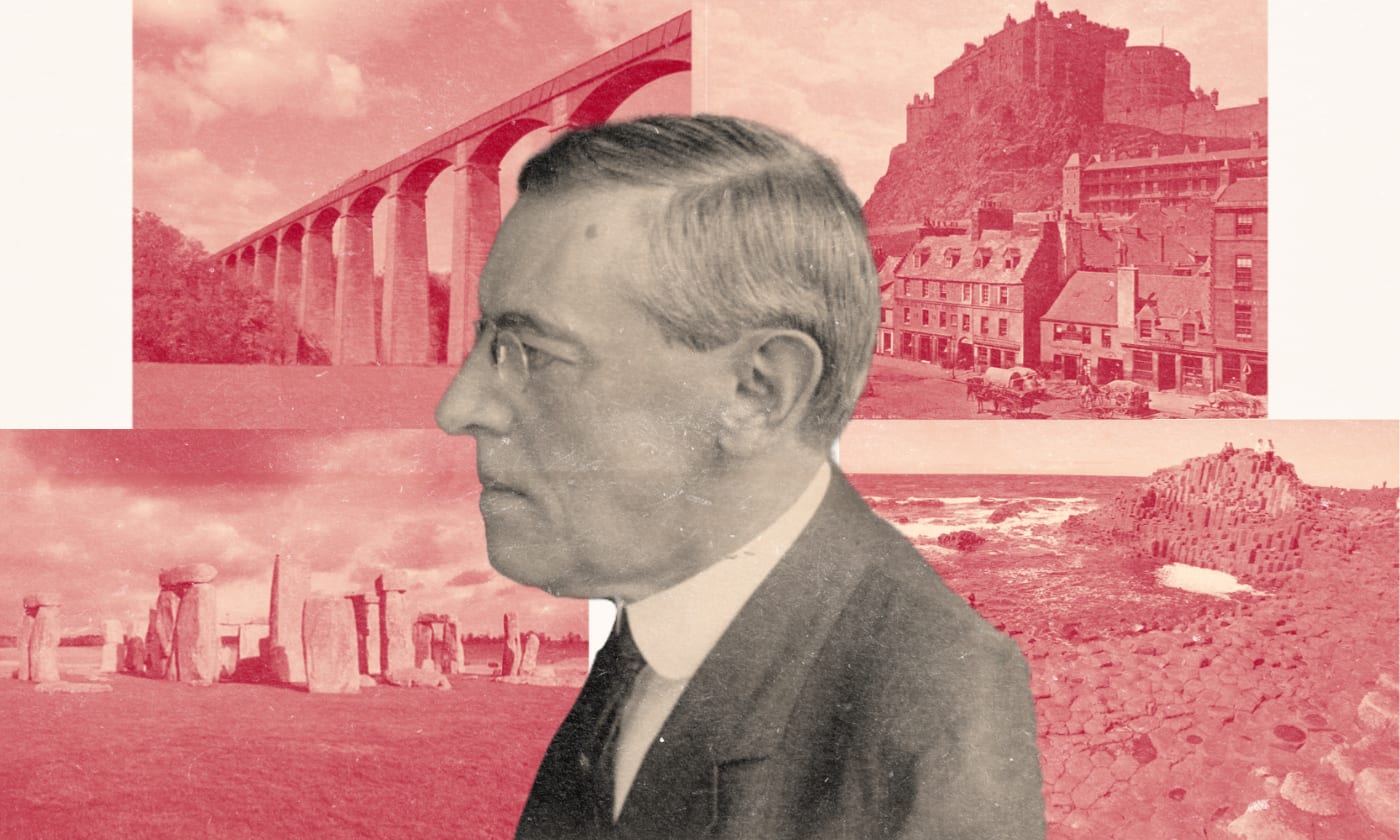

Woodrow Wilson left behind a legacy of would-be idealism most aptly characterised by his Fourteen Points speech he delivered before the United States Congress on January 8th, 1918. The end of World War I would arrive ten months later.

The armistice signed on November 11th, 1918 signified the “war to end all wars”. Euphemisms of never again resonated with the war-weary peoples of Europe. Nations like Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, seemingly born out of thin air, signalled a new era of self-determination for peoples formerly part of the great empires of Europe.

Wilsonian idealism cannot be understood without first having a working understanding of internationalism; what does it mean, and how can it be achieved based on what we know about its historic failures?

A war to end all war requires an unbreakable peace. Post-1918, this was punctuated by making examples out of Germany’s “Teutonic Warlords” materialising in the Treaty of Versailles laying out punitive reparations for the defeated, with Weimar Germany bearing the brunt of its cost.

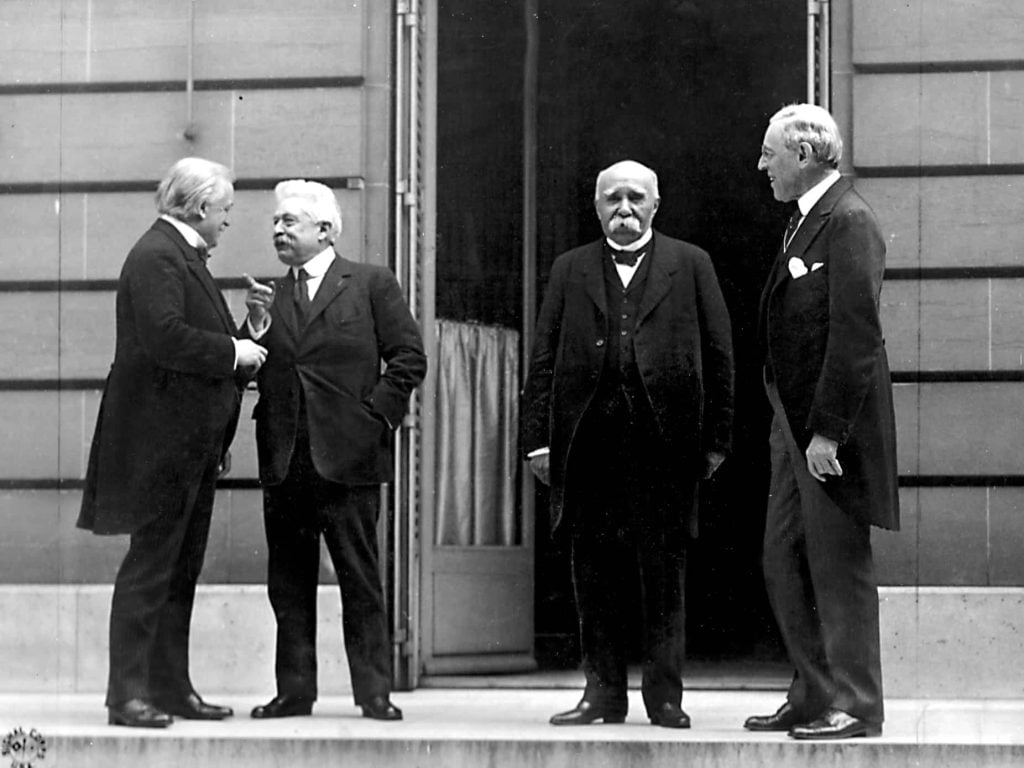

Caption: The four leaders of the biggest nations at the Paris Peace Conference on May 27, 1919. In order from left to right: David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau, and Woodrow Wilson.

One of the greatest legacies of World War I culminated in a certain “tumultuous idealism” birthing the League of Nations, the world’s first supranational organisation as we understand the post-Westphalian concept today. Recognising the shortcomings of the League, the framers of the United Nations Charter sought to create a more effective supranational organisation. Yet, the question remains: has the UN fared any better in achieving its goals?

History seemed poised to repeat itself when full-scale warfare returned to Europe on February 24th, 2022 with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Returning to 1921, when Woodrow Wilson departed the presidency of the United States, he eventually reneged on his idealism and became a realist favouring isolationism. Out of sight, out of mind; the quintessential thinking supporting the dedicated isolationist!

This became the new mantra of American diplomatic thinking during the postwar period of the last century. If the Versailles Treaty taught us anything, it is that peace cannot be achieved, let alone shared by starving the vanquished into a state of existential denial. Yet, any student of history cannot resist wondering: is an armistice the same as unconditional surrender?

The squalor of Weimar Germany is suggestive of a greater reality of sociological purgatory permeating Europe. This made ideal breeding grounds possible for fascists like Adolf Hitler to communist revolutionaries that originated the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic.

The lesson here is that conceptual catechisms like national destiny can go horribly wrong when romantically conjugated as ideologies of national salvation. However, there is another aspect of Wilson’s legacy that offers a more positive and constructive vision: the origins of the United States National Park Service, which is often overlooked as a minor footnote in world history.

Lessons from the United States’ National Park Service for Global Ecological Preservation

Aside from his advocacy of idealism turned internationalism, Woodrow Wilson was also one of the founding fathers of the National Park Service. The stated mission of the agency is to preserve the ecological and historic integrity of places like the Grand Canyon in Arizona and the Albert Einstein House in Princeton, New Jersey for maximum accessibility to the public and for of future generations.

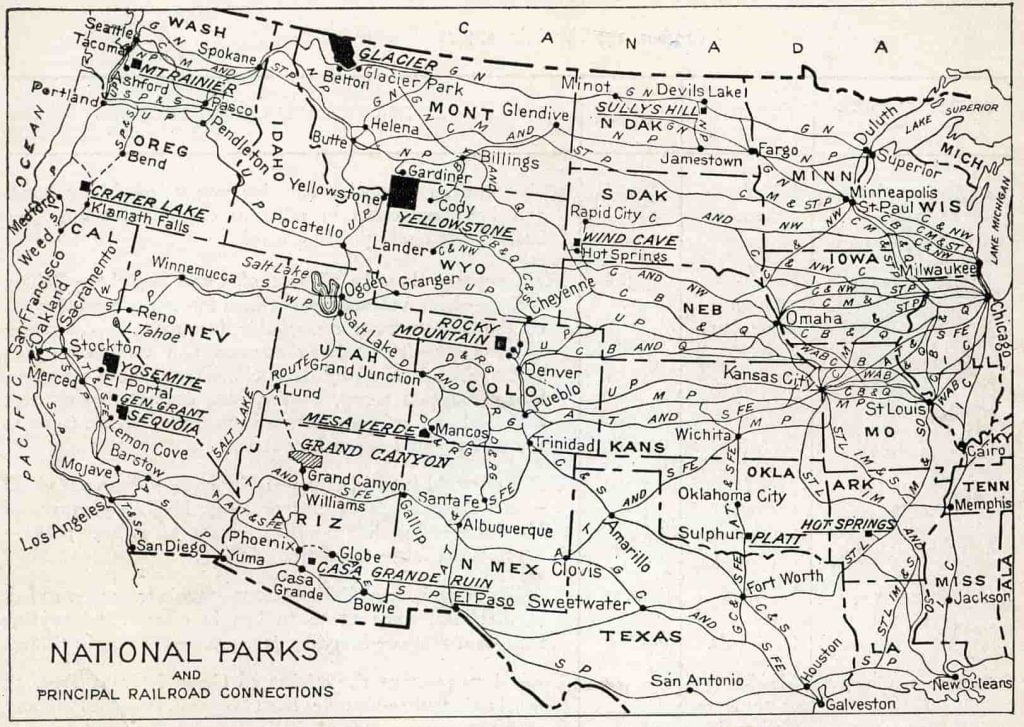

To promote interest in national parks, a portfolio of nine major parks was created in 1916, complete with maps showcasing the parks and their main railroad connections.

The National Park Service actively oversees 85 million acres of protected land and historic places, made possible with an annual budget of $3.265 billion to fund the agency’s mission. However, there isn’t a United Nations equivalent to such an agency. Implementing movements for ecological peace under the working jurisdiction of a supranational authority could help save and preserve natural and man-made wonders of the world, thereby maintaining and extending humanity’s shared heritage.

Creating a UN-led Global Park Service Initiative

Imagine the United Nations developing an organisation similar to the United States’ National Park Service, but as a more expansive supranational project: the World Ecological and Historic Park Service. The feasibility of such an area of supranational governance being competently and effectively instituted by the United Nations in its current configuration is up for debate.

A proposed supranational agency would likely focus on “at-risk nations” throughout the Global South, which are plagued by corruption, economic collapse, and deteriorating infrastructure. National governments might be asked to relinquish sovereignty over their wildlife reserves to invest in their sustainable development and protect against illegal activities. In exchange, an outstanding balance of national debt could potentially be hedged or forgiven by an issuing body like the World Bank or International Monetary Fund, offering tangible incentives to developing nations in the Global South.

As these ideas evolve into potential implementation, more questions arise regarding the practicality of such a system. For example, securing a wildlife preserve in a volatile nation recovering from a recent civil war might necessitate deploying United Nations Peacekeepers to maintain security. Furthermore, these “benign supranational interventions” could serve as havens of socio-economic stability and renewal, incrementally evening out the developmental playing field in the Global South and using United Nations aid to build rather than handicap.

An agency like the World Ecological and Historic Park Service could assist with managing everything from wildfires and protecting our shared historic heritage to replenishing natural resources for the benefit of each nation hosting a site. The question remains: where should such an ambitious initiative begin?