Diving Into the Enigmatic World of Deep Sea Creatures – A Photo Essay

Step into the captivating and unknown realm of the deep sea, where a vast variety of extraordinary creatures dwell, still largely unknown to humans.

Despite the challenging conditions of the deep sea, life thrives in this surreal world. The pressure can be unfathomable, temperatures can plummet to subzero, and darkness is all-consuming, yet a vast array of life forms, ranging from bioluminescent jellyfish to colossal squids, showcase exquisite diversity and beauty.

The deep sea is an enigmatic and mesmerising environment that never ceases to amaze us with its extraordinary inhabitants. Join us as we embark on an extraordinary expedition to the unfamiliar, as we unravel the wonders of the deep sea and the creatures that inhabit it.

Sea Spider

Welcome to the captivating world of sea spiders. These peculiar creatures, despite their name, do not belong to the arachnid family, but rather to the class Pycnogonida. They inhabit oceans across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and are distinguishable by their long and spindly legs, which can be up to ten times the length of their body.

A see spider on a bamboo coral that had been taken over by yellow parazoanthids at at 1,675 meters. Photo NOAA Ocean Exploration/Flickr © CC 2.0

These legs are not used for walking, as you might expect, but for breathing. Sea spiders lack respiratory organs like gills or lungs, so they rely on their long legs to absorb oxygen from the seawater.

Another curious feature of sea spiders is their tiny size. Most species are only a few millimetres in length, making them some of the smallest arthropods in the world. However, some deep-sea species can grow up to 0.3 metres in length, making them giants in the world of sea spiders.

Some species have evolved sharp, hook-like claws to capture small prey, while others have elongated proboscises to pierce and extract the juices from soft-bodied animals such as jellyfish.

An impressive sea spider (Colossendeidae) spotted at a depth of 1,495 meters. Despite their spider-like appearance, pycnogonids are not true spiders. Photo NOAA Ocean Exploration/Flickr © CC 2.0

Despite their size, sea spiders make a crucial part of the ocean’s ecosystem, and their distribution throughout various depths and environments is remarkable. As both predator and prey, they are preyed upon by larger creatures such as fish, crabs, and sea stars, but they themselves consume small planktonic animals, playing a significant role in controlling their populations.

Giant Isopod

Deep in the dark and inhospitable depths of the ocean, there lives a creature that belongs far beyond the reach of sunlight. Meet the giant isopod – a distant relative of the pill bugs found in our gardens, but much, much larger. Some can grow up to nearly 0.6 meters long, making them one of the biggest members of the isopod family.

Giant isopods can go without food for up to five years. This massive creature (Bathynomous gigantus) was photographed during a deep-sea expedition off the southeastern United States. Photo: NOAA Ocean Exploration/Flickr © CC 2.0

But what truly sets the giant isopod apart are its remarkable adaptations that allow it to survive in this harsh environment of 2,140 metres. Its tough exoskeleton protects it from the crushing pressures of the deep and from predators such as sharks and whales. It has a slow metabolism that enables it to go without food for months, a crucial trait in a world where resources are scarce.

Yet, the giant isopod is not defenceless. Its long antennae and large eyes allow it to sense even the faintest traces of light in the dark. It has hooked claws at the end of its legs that help stabilise it on the ocean floor, allowing it to patiently wait for food sources like crab flesh and marine worms that fall from the surface.

Thanks to its large size and hard exoskeleton, the giant isopod has few predators. Its slow metabolism also means it can wait for years to obtain the nutrients it needs to survive. Females of this remarkable species carry their eggs in a brood pouch located on the underside of their body. Once hatched, the young isopods are fully formed and ready to embark on their journey into the deep sea.

The underside of a male giant isopod. This creature was captured in the Gulf of Mexico in October 2002. Photo: NOAA © Public Domain

Glass Sponges

Glass sponges belong to the class Hexactinellida and are truly unique and captivating creatures. These sponges earned their name from their striking spicules, which are made of silica and have a glass-like quality.

Photo: NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

Some species of glass sponges have an extraordinary talent for producing massive spicules that interconnect in intricate patterns, creating a breathtaking “glass house”. Even after the sponge dies, this skeleton can remain intact for years to come, serving as a fortress against predators.

While the spicules and other chemicals offer defence against many predators, glass sponges still have their share of foes in the deep blue. Certain starfish, for example, are known to feed on these rare and fascinating creatures of the deep.

Glass sponges mostly live attached to hard surfaces, where they filter small bacteria and plankton from the surrounding water. These intricate skeletons also provide a home for many other sea creatures in the ocean.

An eye catching yellow glass sponge at a depth of 2,479 meters (8,133 feet). Photo: NOAA Ocean Exploration/Flickr © CC 2.0

Perhaps the most famous of these glass sponges is Euplectella, otherwise known as the “Venus flower basket”. This sponge has a remarkable method of building its skeleton, creating a trap for a certain species of crustacean inside for life. Inside the basket, a pair of small shrimp-like Stenopodidea, one male and one female, live out their lives, breeding and cleaning the sponge.

As the offspring grow, they eventually escape the basket to find a new Venus flower basket of their own, while the original pair is forced to stay put for the rest of their lives. This remarkable and intricate relationship between the sponge and the crustaceans is just a small part of the marvels and wonders of the deep waters.

A glass sponge on a seamount outside Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Photo: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research © Public Domain

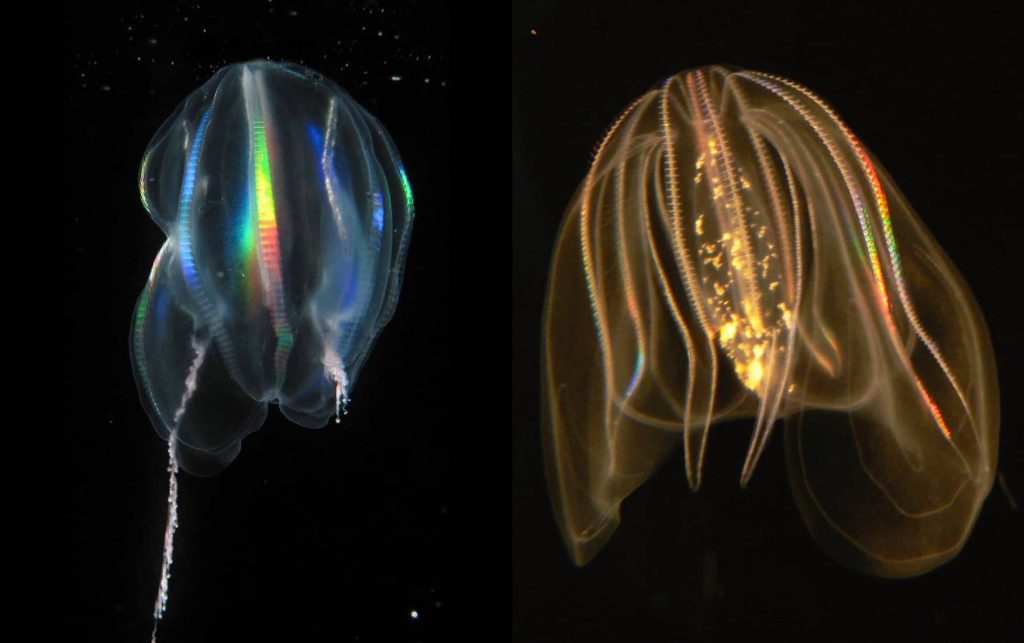

Comb Jellies (Ctenophora)

The comb jelly, a stunning creature with an oval shape, is equipped with eight rows of comblike plates that it uses to propel itself through the water. These rows diffract light as it swims, producing a beautiful rainbow effect.

Right: The species formerly referred to as “Tortugas red”, now identified as Nepheloctena spp, has tentacles that trail behind and visible secondary branches, also called tentilla Photos R. Griswold/NOAA. Left: An example of a ctenophore, Bathocyroe fosteri, which is a mesopelagic species Photo: Marsh Youngbluth © Public Domain

Some comb jellies can expand their stomachs to consume prey nearly half their size, making them fierce predators of other jellies.

Despite their simplistic biology, jellies are equipped with certain features that help them survive in their environment. For example, most comb jellies can detect chemical traces in the water to locate food, and they have a structure called a statocyst, which helps with orientation.

However, these unique creatures are also sensitive to changes in water quality during certain stages in their life cycle, making them an indicator species for larger environmental problems.

One fascinating aspect of the comb jelly’s biology is that it is made up of more than 95% water, allowing its thin skin to stretch and move with ease. Despite their otherworldly appearance, jellies are perfectly adapted to their environment and play an important role in the ecosystem of our oceans.

Photo: Orin Zebest/Flickr CC 2.0

Right: When the rows of combs on a Mertensia ovum diffract light, the tentacle on the left side is extended while the one on the right is pulled back © Public Domain. Left: Comb jelly from the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo Jennifer Krauel/Flickr

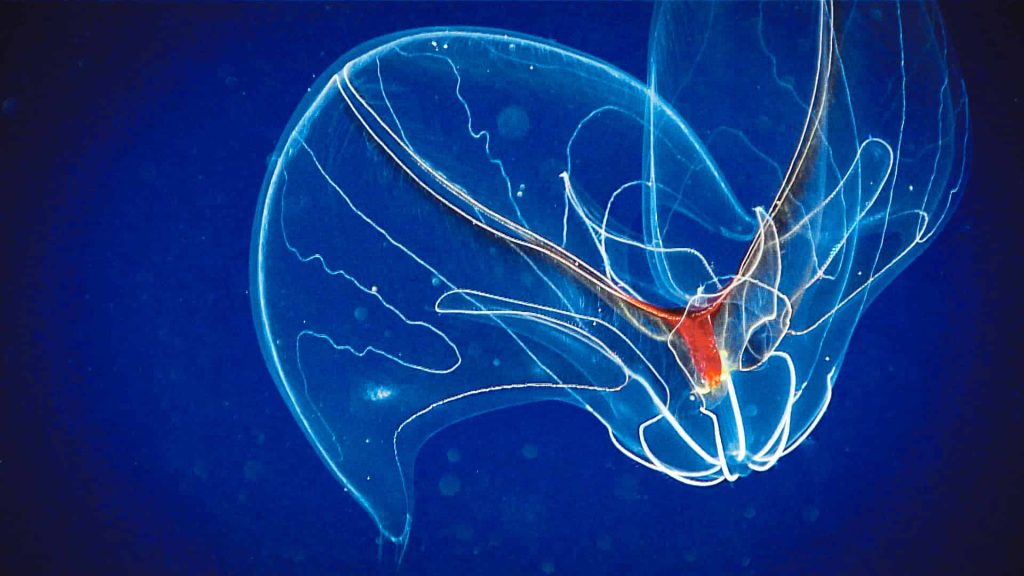

The ctenophore’s outer edge shimmered with iridescent greens and blues, caused by light refracting off the numerous combs or ctenes, which the creature employs to swim in the water column. These ctenes are composed of fused flagella, making ctenophores the largest animals that use flagella as their primary mode of locomotion. Photo NOAA Ocean Exploration © CC 2.0

A ctenophore, or comb jelly, photographed at the Gulf of Mexico 2018. In the photo, the ctenophore’s mouth is facing upward, and the converging white lines lead to the “apical sensory organ” that helps the ctenophore orient itself in space. Photo: NOAA Ocean Exploration © CC 2.0

Deep-sea Dragonfish

In the depths of the abyssal plains, there lurks a creature that appears to have plucked out of a sci-fi film. It is as though the fearsome Venom has been miniaturised into a fish form. However, this is no fictional fabrication. This is the real and extraordinary Deep-sea Dragonfish, every bit as captivating as its make-believe doppelganger.

The head of the Malacosteus niger, commonly known as the black dragon fish. Photo: ESRI, Dr. Beinart, Tracey T. Sutton © CC 4.0

The Deep-sea Dragonfish, also known as the Scaleless Dragonfish, is a real-life wonder of the deep. This fierce predator, scientifically named Grammatostomias flagellibarba, say that 10 times, may only measure around 15 centimetres in length, yet it possesses a large head and a mouth full of sharp fangs that can impale and grasp its prey with ease.

What truly sets the Deep-sea Dragonfish apart is its remarkable bioluminescence. The Dragonfish has photophores, specialised organs located on its chin and body, that emit a blue-green glow thanks to bacteria within them.

Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra © CC 2.0

The Dragonfish can even use its barbel, a protrusion from its chin tipped with that photophore, as a fishing lure to attract unsuspecting prey. These lights also serve to attract potential mates and disorient predators.

Living at depths of up to 1,500 metres mainly in the North and Western Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, the Deep-sea Dragonfish is a true survivor of the abyss.

It has a range of physiological and behavioural adaptations that allow it to thrive in an environment that is inhospitable to most other creatures. For example, its highly efficient metabolism helps it conserve energy in a resource-poor environment, and a specialised bladder helps it control its buoyancy.

Closeup Image of a Dragonfish Jaw Photo: David Baillot © CC 2.0

The Dragonfish’s large teeth and ability to capture small fish and crustaceans in the dark depths of the ocean make it a fearsome predator. The walls of its stomach are even black to conceal the light produced by its prey as it digests its meal. As an external spawner, the female releases eggs into the water for fertilisation, and the larvae are left to fend for themselves until they reach maturity.

Despite its deadly hunting skills, much about the Deep-sea Dragonfish’s life cycle and habits remains a mystery. But its remarkable bioluminescence and sharp teeth make this creature a true wonder of the deep sea.

Nautilus

The Nautilus is an incredible living link to the ancient past, having been around for over 480 million years and cruising deep ocean reefs even before the time of dinosaurs.

This soft-bodied cephalopod lives inside an intricately chambered shell that can grow up to 20 cm in diameter. While its simple, pinhole-type eyes can only sense dark and light, the Nautilus has a highly developed sense of smell and can perceive water depth, current directions and speeds to help it keep its body upright and search for food and mates.

Photo: Manuae © CC 3.0

Found in the Indo-Pacific on reefs and pilings, the Nautilus preys on small fish and crustaceans and scavenges the remains of other animals. Its tentacles, which are coated with a sticky secretion and lack suckers or hooks, help it feel and grope along the reefs for food.

To avoid predators during the day, Nautiluses linger along deep reef slopes, sealing themselves inside their shells using a hood-like trapdoor for protection. At night, they migrate to shallower depths of about 70 metres to feed and lay their eggs.

Unlike other cephalopods, a Nautilus’s tentacles have grooves and ridges that aid in gripping and passing food to its mouth. It uses its sharp, beak-like mouth to break food apart, and its radula, a band of tissue lined with tiny teeth, to shred it further. To swim, the Nautilus uses jet propulsion, expelling water from its mantle cavity through a siphon located near its head.

While most cephalopods are short-lived, a Nautilus can live for over 20 years, reaching maturity in 12 to 15 years. Females lay relatively few eggs, between 10 and 18 per year, which take about 12 months to hatch. The Nautilus pumps fluids in and out of its shell chambers, connected by a tube called a siphuncle, to control its buoyancy and swim forward, backward, or sideways.

The rudimentary eye on the head of N. pompilius operates comparably to a pinhole camera.

Sadly, Nautiluses face threats from overfishing and habitat destruction. Collectors seek their shells for their beautiful mother-of-pearl linings and red-striped, cream-coloured exteriors.

This demand has resulted in significant declines in Nautilus populations. In 2017, the chambered Nautilus was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Siphonophorae

As we journey deeper into the shadowy and enigmatic depths of the ocean, we come across a captivating group of marine creatures known as Siphonophorae, belonging to the esteemed phylum Cnidaria.

Despite the World Register of Marine Species identifying a staggering 175 species, these colonies of specialised medusoid and polypoid zooids are nothing short of extraordinary. At first glance, Siphonophorae appear to be solitary beings, but they are, in fact, composed of numerous genetically identical zooids, each with its own unique function.

A beautiful siphonophore. Photo: NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

These zooids operate in harmony, utilising the process of budding to construct colonies capable of reproduction, digestion, buoyancy control, and even jet-like movement for propulsion.

These captivating creatures showcase an astonishing range of shapes and sizes, with some stretching to an impressive 40 meters in length. While most Siphonophorae call the pelagic zone their home, certain species have adapted and thrived in the benthic environment.

Siphonophorae are formidable hunters, employing their tentacles to ensnare small crustaceans, copepods, and even minuscule fish. Their distinctive propulsion method involves smaller zooids managing the colony’s orientation while larger individuals produce the necessary thrust for motion.

But what sets these creatures apart is their extraordinary ability to emit bioluminescent light. Certain species use this dazzling light display as a defence mechanism, while others utilise it to lure prey. Only a handful of Siphonophorae possess the capability to produce red light, which is a rare attribute in the animal kingdom.

© Public Domain

Siphonophores are frequently observed in the midwater region and have a unique colonial structure where individuals within the colony perform specialised tasks. Photo: NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

Barreleye

The deep, dark waters of the Pacific Ocean are home to an unusual and fascinating creature, the Barreleye fish. This fish belongs to the Osmeriformes order and is a relative of smelts. Typically growing up to 15 centimetres in length, this peculiar fish is known for its distinctive eyes, which are two bright green upward-pointing orbs visible through the transparent dome on its forehead.

The Macropinna microstoma fish has a unique tubular and upward-facing eyes protected by a transparent hemispherical capsule, which can create the illusion of a transparent head. The indentations at the front of the head are olfactory organs, not eyes, and the true eyes can rotate forward. Photo: Kim Reisenbichler © CC 4.0

While the Barreleye’s eyes primarily point upwards to spot prey swimming above it in the water column, the fish can also rotate its eyes forward to see its food while eating.

Barreleye fish live in the ocean’s twilight to midnight zones, usually between 600 and 800 meters. This depth range is where sunlight from the surface fades into darkness, creating the ideal habitat for these ultra-sensitive-eyed fish. They feed primarily on zooplankton, including crustaceans and siphonophores.

Despite their small size and elusive nature, the Barreleye fish’s unique adaptations have fascinated scientists for decades. Their large, flat fins allow for precise manoeuvring and near-motionless hovering in the water column. However, this fascinating creature remains a mystery in many ways, with little known about their reproduction and life cycle.

Goblin shark

The Goblin shark is an unusual species of shark that inhabits the depths of the ocean. With its shovel-like snout, flabby body and a tail with a weakly developed lower lobe, the Goblin shark is a unique sight to behold.

Photo: Dianne Bray/Museum Victoria

One of its most distinctive features is its protrusible mouth, which can retract under the eye or extend forward under the snout. This is an adaptation that allows the Goblin shark to quickly capture its prey, which includes bony fishes, squids and crustaceans.

The Goblin shark’s long, pointed teeth and heavily pored underside of the snout are features that allow it to hunt using its highly developed electro-sensory system. The ampullae of Lorenzini, which are the external openings of the electricity detecting organs, help the Goblin shark to detect electric fields and track its prey in the dark waters.

A Goblin shark. Photo Kelvin Aitken

Despite its fearsome appearance, the Goblin shark is not considered dangerous to humans, as it lives in deep water and is rarely encountered.

The Goblin shark, which is named after Alan Owston, an English collector of Asian wildlife, is found in scattered locations across the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. It typically lives close to the ocean floor in marine waters up to a depth of 1,200 meters. In Australia, sightings of the Goblin shark have been reported off the coasts of New South Wales, Tasmania, and potentially South Australia, as per the Atlas of Living Australia.

Dumbo Octopus

The Dumbo octopus, known for its elephant-like ears, is a deep-sea dweller that lives in the open ocean at extreme depths of at least 4,000 metres and possibly much deeper. These depths present harsh living conditions that include cold water and the complete absence of sunlight.

Photo NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

Despite this, Dumbo octopuses have specialised behaviours to increase the likelihood of successfully reproducing when a mate is found. Female Dumbo octopuses carry eggs in various stages of development, and can store sperm for long periods of time after mating with a male, transferring it to their most developed eggs whenever environmental conditions are optimal. They lay their eggs on the seafloor, attaching them to rocks or other hard surfaces.

Dumbo octopuses are primarily foraging predators and feed on pelagic invertebrates that swim above the sea floor. They move by flapping their ear-like fins and steering with their webbed arms. Large predators are rare in the deep sea, so Dumbo octopuses’ primary predators are diving fishes and marine mammals like tunas, sharks and dolphins. Due to their preference for extreme depths, they are only very rarely captured in fishing nets and are not considered threatened by human activities.

The dumbo octopus use their ear-like fins to slowly swim in variuos directions. Photo NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

The Dumbo octopus is the deepest-living of all known octopus species, and they are named after Disney’s Dumbo the elephant character, famous for its large ears.

Unlike most octopuses, the Dumbo octopus lacks an ink sac since it encounters predators rarely in the deep sea. The largest Dumbo octopus ever recorded was 1.8 metres long and weighed 5.9 kg, but most species have an average size of 20-30 centimeter long.

This dumbo octopus, known as Cirrothauma murrayi, is a rare species commonly referred to as the Blind Octopod because its eyes lack a lens and retina, rendering them incapable of producing visual images and only allowing them to detect light. Photo: NOAA Photo Library © CC 2.0

In the depths of the ocean, life takes on a different form, with adaptations that seem almost otherworldly. The above creatures remind us of the incredible diversity and resilience of life on our planet, and their fascinating features continue to astound and intrigue scientists around the world.

So perhaps next time you find yourself by the seashore, take a moment to appreciate the wonders that lie beneath the waves.