Five nations, one failure: The Security Council's deadly indifference to hunger

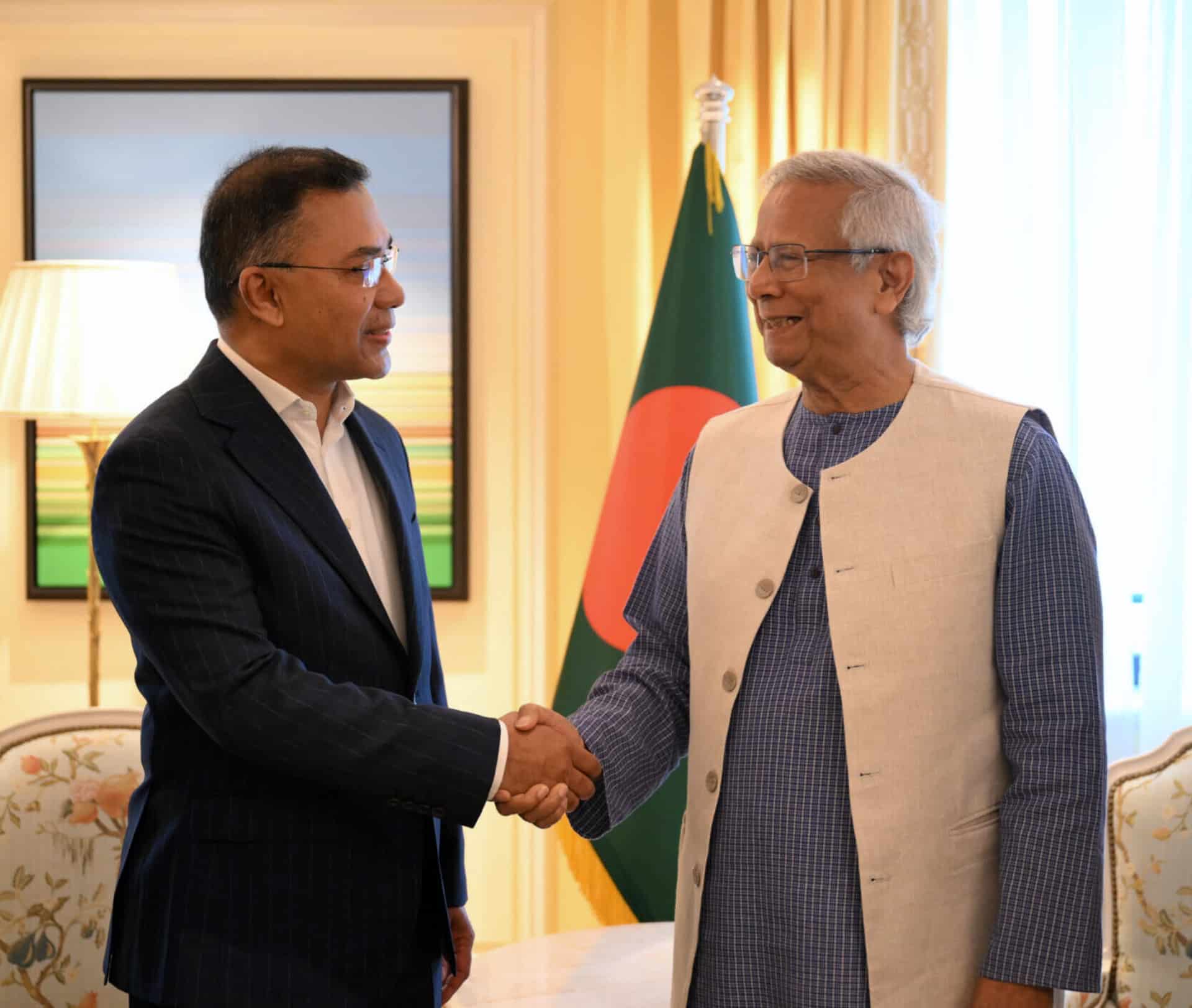

Born from the ashes of world war, the Security Council promised protection and peace. Today, its veto powers ensure silence as millions starve.

We are a quarter of the way into the 21st century – an age of unprecedented global connection, advanced consumer technology, and artificial intelligence. The first world has become an oasis of comfort and convenience, though the rest of the planet still struggles with basic needs. Hardship can be simply uncomfortable – some can’t cover unexpected costs or buy property – but for others, it is an agonizing fight for survival. These are the 295.3 million people experiencing acute food insecurity.

It’s no secret that former colonies – lands and peoples drained of resources and wealth for centuries – see the highest levels of poverty, disease, violence, and hunger. These nations fought the post-independence hurricane of statecraft, economic development, governance, and globalization with paper umbrellas. Production was minimal, governments overspent, corruption abounded, armed rebellions ensued… and if one remembers for the general disadvantage in competing with nations two-hundred years ahead, these countries could not be further from first-world comfort.

Despite the brutal aftermath of colonial rule, the primary obstacle to food security in 2025 is conflict. In fact, because of conflict-related displacement (movement restriction in the case of Gaza), a combined two million from Palestine, Sudan, South Sudan, Haiti, and Mali are at imminent risk of death from starvation. These are the kinds of outcomes that the United Nations was designed to prevent.

Following WWII, after years of global chaos and 60,000,000 deaths, the powers of the world formed the United Nations, determined to never allow history to repeat. In 1948, swelled with this resolve, the UN authored the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – rights deemed inalienable to everyone. These include:

- The right to life and the security of person (Article 3)

- Protection from torture or inhuman treatment (Article 5)

- The right to an adequate standard of living, including food (Article 25)

Actors of violent conflict, by preventing entire populations from accessing food, continuously violate the human rights of millions – and the United Nations Security Council lets them.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is the primary international body with the authority, means, and obligation to defend these rights. Through powers granted by the UN Charter, they can respond to events that challenge international security and peace with decisive force. These are the people with the power to move mountains.

Instead, what we see today is a handful of clueless, apathetic representatives from five nations that have turned the world’s shield against global crises into a forum for interstate bickering and leveraging political grievances. Life-saving resolutions are vetoed in the name of political theater, but those most impacted are completely uninvolved. The Security Council acts as such because it has grown to regard conflict as an acceptable constant, instead of a peril threatening four times as many lives as World War II. In fact, the P5 is proving in recent years that it may be the biggest obstacle to food security.

Let’s look at a few recent examples of the P5 preventing life-saving action by abusing their veto power.

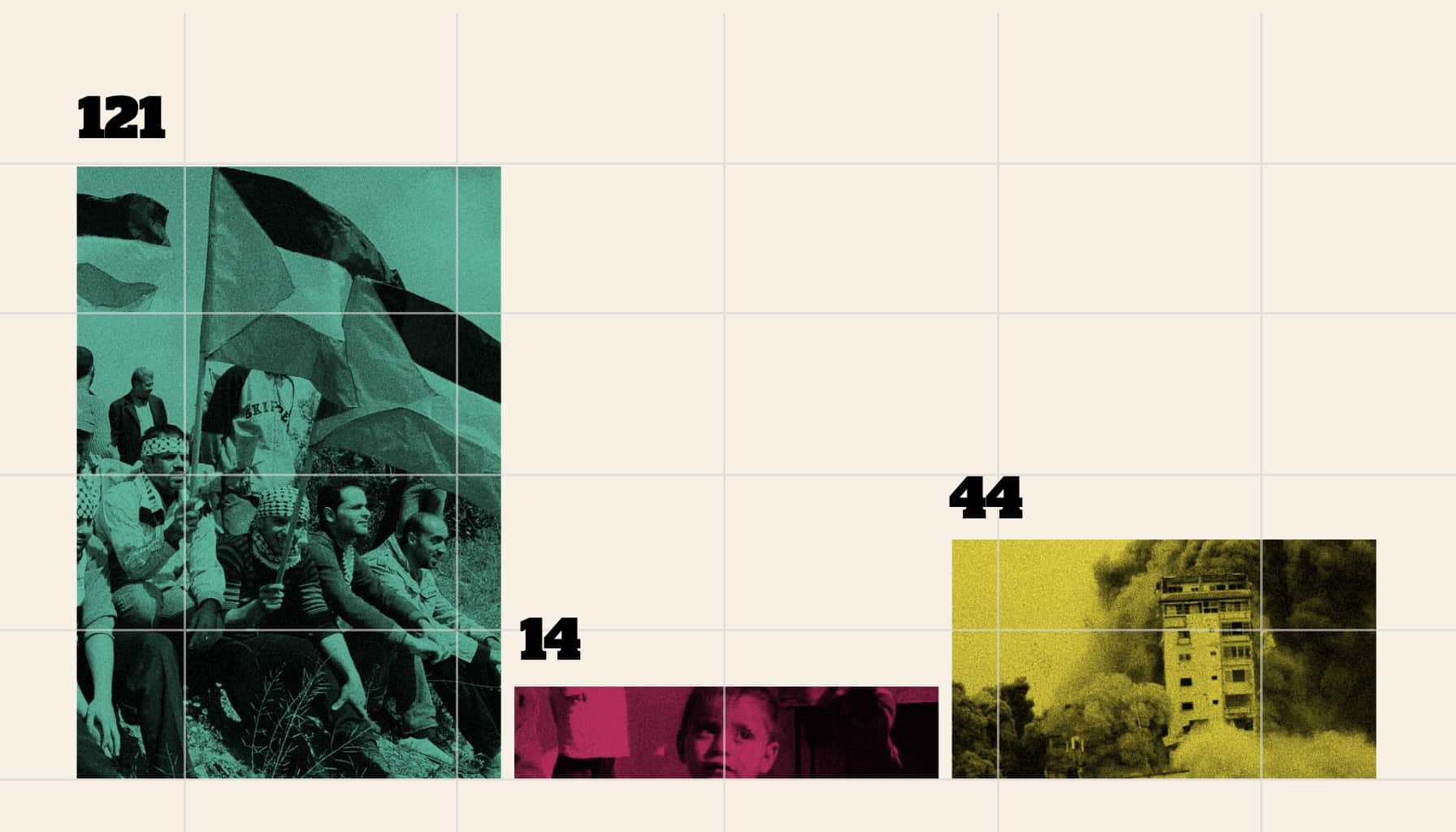

In 2020, Russia and China vetoed a resolution that would permit the delivery of necessary food and medical supplies to millions of Syrians – not in the name of international security or to offer a more strategic approach. It was simply an expression of learned disdain for the West and a strategic nod to Bashir al-Assad and his “authority” – which isn’t worth much today. Simply put: because of nostalgic anti-West sentiment and authoritarian insecurity, they decided that millions of lives were not worth saving.

In 2024, Russia vetoed a resolution that called for armed rebels to halt attacks against civilians in Sudan and allow aid to be delivered. Once again, it was out of Cold-War-era animosity and the deeply troubling misconception that the Security Council is “not obliged” to protect civilians. As a result, a resolution to effectively address the conflict fueling Sudan’s food insecurity was denied because of one nation’s selective interpretation of the Council’s priorities; millions of lives were disregarded because of the unrelated political sentiment of a single government – an issue having nothing to do with the ongoing crisis.

And most recently, in June of 2025, the United States vetoed a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza, where 100% of the population is experiencing acute food insecurity. The resolution demanded the release of all hostages and removal of all Israeli restrictions on aid. Now, with the recent confirmation of famine, it is clear that the US veto will result in thousands more preventable deaths. US Ambassador Dorothy Shea, despite a death toll of 60,000 and the complete ruination of Gaza, claims that more needs to be done to hold Hamas accountable. Translation: Israel wants more Palestinians to die. Therefore, as long as these veto powers exist, the entire UNSC will be influenced by the bloodlust of one genocidal nation.

Thus, because of the P5’s appalling abuse of veto powers, it is clear that the power should not exist in the first place. The council seems to have lost sight of why the United Nations was formed and what the role of the Security Council is. Instead of taking up a role of service and protection, staying true to the purpose of the Council, these delegations have reduced it to a room full of fake altruists that routinely overlook threats to millions of people and violations of their rights. What’s most insulting is that we have never – in all of human history – been better equipped to tackle such challenges. It’s a matter of choice.

The self-appointed P5 were simply the victors of WWII. They institutionalized their dominance in the context of the post-WWII world order. Now, in the face of 21st century challenges, it is increasingly obvious that this appointment is functionally arbitrary and inappropriate. If this power structure remains, the United Nations could be directly responsible for a scale of devastation larger than it was designed to prevent.

A Security Council with several rotating seats is not inherently problematic. As long as member states are appointed in a way that is fair, strategic, and promotes international security, effective resolutions can be drafted and agreed upon with a majority vote. Once resolutions can be approved without extraneous politics, and after the UNSC as a whole realigns with its foundational priorities, the world’s biggest crisis will finally be met with the best foot forward.