What is the World Atomic Weapons Disarmament Agency (WAWDA) and why do we need it

The IAEA has successfully preserved the spirit nuclear disarmament, but today we know that the enforcement of international law fails without a multilateral body of enforcement.

The International Atomic Energy Agency was established on July 29th, 1957, to relegate atomic energy exploits for peaceful purposes. The idea was to deny the militarization of atomic weapons, but how successful has the same agency been in working toward a future free of nuclear weapons?

Russia’s unilateralist war in Ukraine was a rude awakening as fears of nuclear war returned to the public discourse. Unfortunately, we live in a reality where not every concerned world citizen is also a world federalist. This is most evident in national societies inhibited by limited free assembly. In controlled societies where official state discourse assumes supreme precedence over the individual discourse of citizens, disconnects in communicating the mission of world federalism will remain a tremendous challenge for global audiences.

The collapse of Soviet communism brought us a world dominated by unilateral state actors best understood in the brutal language of realpolitik. The question is: are discussions associated with realpolitik practical concerns of world federalists?

Any discussion about the IAEA cannot be had without an overview of its origins. There remains wide-ranging debate about the sole progenitor of the agency, but it is widely believed Dwight Eisenhower is the agency’s first major advocate. During a speech to the United Nations General Assembly in 1953, he proposed an “atoms for peace” initiative. The focus of his speech stressed the demilitarization of atomic energy. Eisenhower affirmed to his Cold War contemporaries that a civilized world community would prioritize atomic energy for civilian use via advancements made in areas of power generation, medicine, and agriculture.

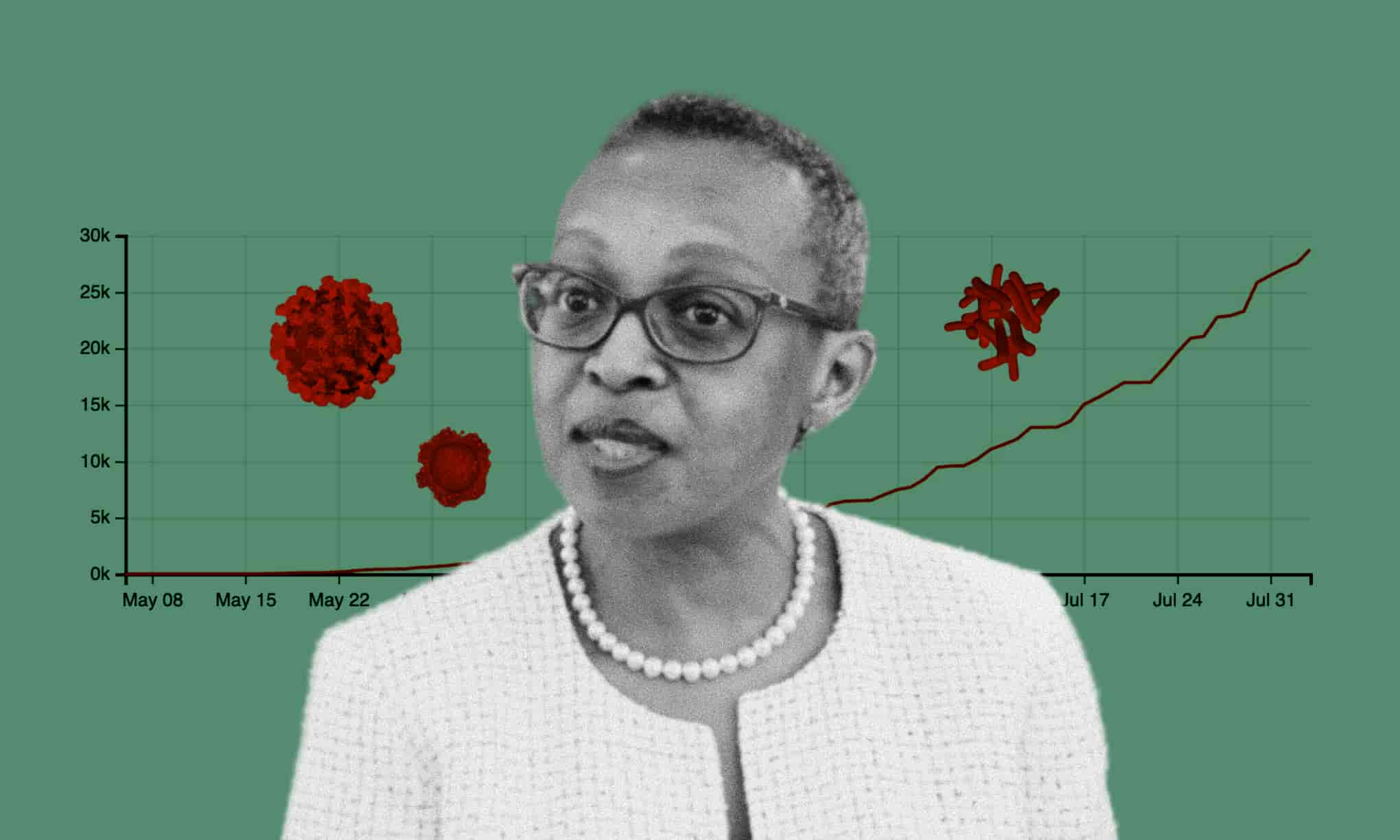

Only nine nations possess 12,700 nuclear weapons

The idea was to replace our view of the atomic mushroom cloud with something definitively more benign and beneficial to humanity. The work of the IAEA has successfully preserved the spirit of this mission to the present day, but the reality of mutually assured destruction did not disappear with the end of the Cold War. Rather, it merely dissipated into politicized obscurity. This fear has returned with a neo-Cold War vengeance as Russian president Vladimir Putin threatened nuclear war to compensate for Russian territorial losses in Ukraine. Yet, where do we go from here when prospecting a future free of atomic weapons, further liberating the world from nuclear war? According to data compiled by the Federation of American Scientists, it was estimated that nine nations possess 12,700 nuclear weapons as of 2022.

Vladimir Putin has stepped up his nuclear rhetoric, pledging to defend Russian territory with “all available means.”

This figure is drastically dwarfed by Cold War highs as seen in the 1980s, but considering the renewed geopolitical surge of revanchism turned unilateralism among single-state actors, how effective can the IAEA be in a world dominated by realpolitik? Did the findings of IAEA weapons inspectors dissuade the United States from unilaterally invading Iraq in 2003? Is a separate organization dedicated to dismantling nuclear weapons outside the jurisdictional controls of the IAEA necessary? Empirical observation confirms the actual enforcement of international law fails without a multilateral body of enforcement.

The basis for such an underlying reality will prove no different when tasked with managing campaigns dedicated to the elimination of nuclear weapons. The world of 2022 is a multipolar one seemingly marked by the endlessness of war. Hope and despair coexist in strange ways where the worst-case scenario can bring out the best in mankind. A total victory against atomic war cannot be achieved without the elimination of nuclear weapons. A separate supranational organization operating in concert with the United Nations without attachments to the Security Council can be tasked with this mission.

As much as we want to eliminate the possibility of nuclear war overnight, it must be realized that such an undertaking can only be achieved incrementally over multiple generations. The foundation for such an organization would be situated on a clause of chartered renewability. This will be measured by a minimum number of nuclear weapons decommissioned, dismantled, and recycled into civilian use every 5 years with reports made available every year.

Enter: The World Atomic Weapons Disarmament Agency (WAWDA). Perhaps the best introduction for the new agency would be renewing America’s Megatons for Megawatts Program, albeit on a worldwide scale, to reintroduce substance to Eisenhower’s dream of atoms for peace. The added focus would be on recycling the half-life of depleted uranium into renewable energy solutions in ways where the atomic structure of each quantity can be rearranged to deny re-weaponization if applied as an energy alternative for developing nations.

The leading nuclear powers must lead the way and WAWDA can provide the necessary guidance under the rule of international law for the unconditional benefit of mankind.