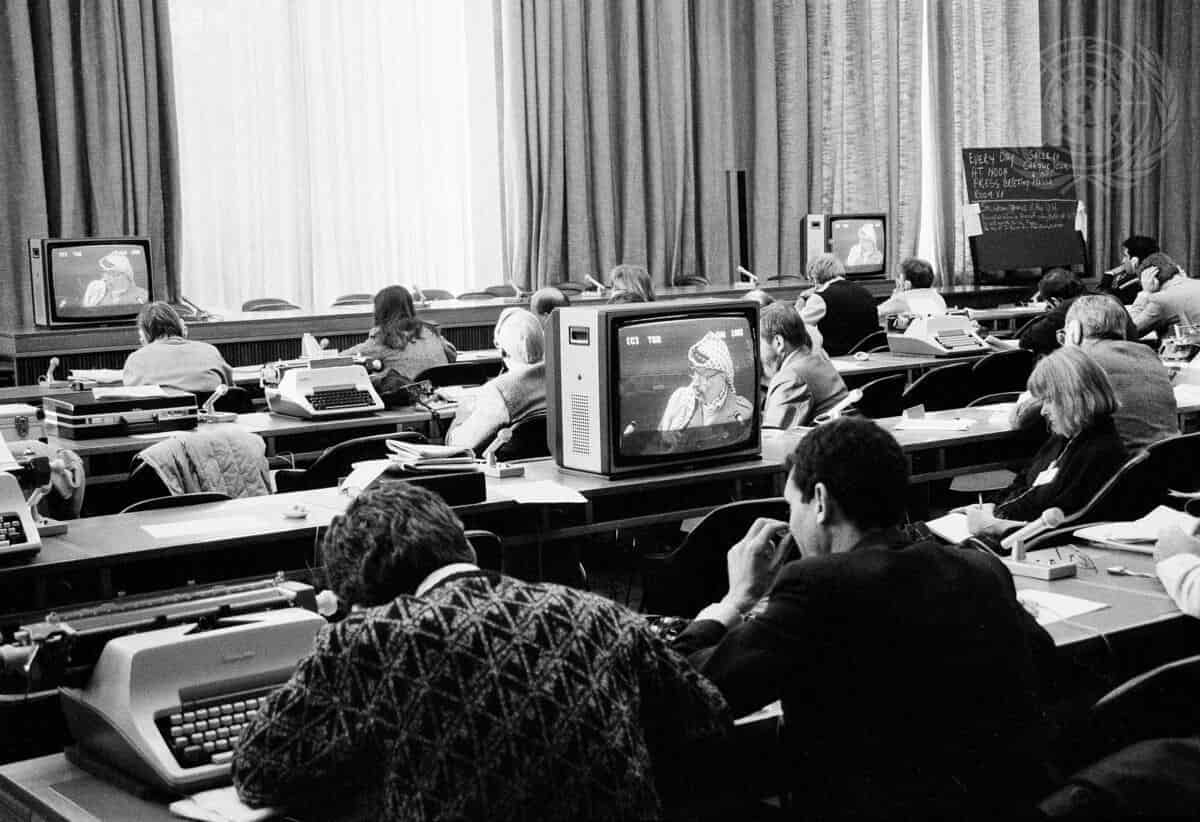

The General Assembly Hall in New York is usually a theatre of protocol, but on 2 December 1988 it became a stage for open defiance. The United States, as host of UN Headquarters under the 1947 Headquarters Agreement, had refused Yasser Arafat, then chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), a visa to attend. Rather than accept the absence of the Palestinian leader, 154 nations voted to take the Assembly elsewhere. Only the US and Israel stood in opposition. Britain abstained.

Zehdi Labib Terzi, the PLO’s veteran observer at the UN, emerged from the vote triumphant. “Once again, within hours, the international body in this community has stood together for what is right against what is wrong,” he told reporters.

A week later, delegates filed into the Palace of Nations in Geneva, once the seat of the League of Nations. Addressing the Assembly there, Arafat reflected on that remarkable 43rd session of the UNGA debates:

“It never occurred to me that my second meeting with this honourable assembly since 1974 would take place in the hospitable city of Geneva … I am both proud and happy to meet with you today after an arbitrary American decision barred me from going to you there.”

“The resolution passed by your esteemed assembly, with 154 member nations voting to move the session here, was not a victory over the American decision but an unprecedented landslide for the international consensus in favour of justice and peace. It is proof that our people’s just cause has become embedded in the fabric of the human conscience.”

That speech coincided with Resolution 43/177, which recognised the proclamation of a Palestinian state and allowed the Assembly to use the designation “Palestine” when referring to the PLO in UN proceedings.

At the time, the symbolism was impossible to miss. Even the Los Angeles Times, reporting from New York, described the relocation as “a slap at Washington” and noted the isolation of the United States and Israel as they stood alone against the overwhelming majority. The episode suggested that, when pushed far enough, the international community would assert itself—even against the host nation of the UN itself.

Today, once again, Palestinian leaders have been denied entry to the United States. In August 2025, the State Department revoked the visas of PLO chairman Mahmoud Abbas and around eighty other officials, silencing their voices even as Gaza endures what UN experts and jurists describe as genocide.

The State Department defended the move as “in our national security interests,” while also urging Palestinians to abandon legal efforts to hold Western perpetrators of genocide and annexation of Gaza and the West Bank accountable, dismissing these as “lawfare campaigns”.

Having provided the Israeli military with the ammunition to kill what Secretary-General António Guterres has called “the highest number of aid workers in UN history”, the US has also imposed sanctions and threatened Francesca Albanese, the Special Rapporteur on human rights in the occupied territories, as well as judges and the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

“There are people inside the Trump administration who are working closely with the right-wing Israeli government, and their goal is to simply remove the Palestinian liberation movement from the international agenda,” says Matt Duss, executive vice president at the Center for International Policy.

“They do not recognise the Palestinian people’s right to a state, and they’re both trying to prevent that on the ground in Palestine and now they’re trying to remove them from the international agenda in New York.”

Inside the UN, the tone is more restrained. Spokesman Stéphane Dujarric says only: “It is important for all states and observers to be represented at the summit. We obviously hope that this will be resolved,” adding that discussions are under way with the State Department about the Headquarters Agreement.

These carefully measured words stand in stark contrast to the boldness of 1988, when, after polite protests failed, the Assembly packed its bags and took its session abroad. The logistics were costly, but the principle was priceless: no state should dictate the UN’s agenda.

The difference between then and now reveals more than a loss of nerve. It speaks to the ways in which the United States has tightened its grip on the global order and ensured that even allies are too timid to resist.

In the late Cold War years, there was still a sense of balance, of blocs that could at least mount symbolic opposition. Today, the US arsenal of coercion is vast and varied.

Economic blackmail has become routine, with the threat of tariffs, withdrawal of trade privileges, or exclusion from financial markets hanging over governments that step out of line.

This power is reinforced by America’s dominance of the dollar and its sway over institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which turn financial lifelines for countries in desperate need into political levers.

Loans and aid come with strings attached, and policy prescriptions often open markets for US companies while shackling debtor states with reforms that serve Washington’s interests.

Entire economies can be strangled through secondary sanctions, and even allies are not exempt, as Europe discovered during Trump’s tariff wars when threats of duties on steel and cars were wielded to bring leaders to heel.

Military dependency runs even deeper. Washington’s rhetoric about NATO “burden-sharing” has become a conveyor belt for its defence industry. The European Union is poised to spend hundreds of billions on American arms under the pretext of arming Ukraine and reinforcing its own security.

Sitting alongside European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen on 27 July, Trump set out what these future EU military investments would be.

“But that’s one number we’re not determining,” he said. “It’s going to be whatever it is, but they’re going to be purchasing hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of military equipment.”

Reliance on allies for arms is not unusual. No European state can feasibly duplicate the entire industrial base of the United States, and some degree of dependency is inevitable. What is striking today, however, is the scale and the political terms of that dependency.

“Historically, there’s this notion that greater cooperation is questionable for sovereignty, and you’ve got to be careful not to share too much of your defence industry with your neighbours,” says Guntram Wolff, a senior fellow at the thinktank Bruegel, speaking to the Guardian.

“But the counter-argument that many are pushing is that at the moment we have a huge dependency on the US. And that means sovereignty doesn’t sit in Europe – it’s in Washington.”

In this climate, the hesitancy of United Nations members is less mysterious.

Palestine has become the UN’s broken mirror: its treatment reflecting not only the silencing of a people but the decay of the institution itself. For decades, the Palestinian cause has been the stage on which the UN rehearses its principles—self-determination, human rights, the end of occupation—only for those principles to dissolve under American vetoes and Israeli bombs.

The contrast with 1988 could not be sharper. Then, the Assembly dared to defend its principles. In 2025, as Palestinians are murdered, it looks away.

Arafat’s words in Geneva still echo, when he said that peace must be made “far from the arrogance of power”. Yet arrogance has seeped into the very heart of the institution meant to contain it. The credibility of the UN is not measured in the number and quality of its speeches but in its willingness to act on its own principles.

- On 22 September, the 80th session of the General Assembly will open in New York, co-hosted by France and Saudi Arabia.