The mirror and the light: Caravaggio and the enigma of Narcissus

When Narcissus emerged from obscurity in 1913, it reignited fascination with a timeless myth and the men who painted its tragedy. Whether born of Caravaggio's brush or not, it reveals the myth's core - the moment when reflection turns to obsession and beauty gives way to loss.

There are certain lights destined to shine beyond the temporal limits imposed by life; lights that transcend ordinary existence, rising above the confines of what is commonly lived or expected. These are lives untouched by convention, detached from rules they neither acknowledge nor feel as their own.

They are the lights of exceptional beings who, though sharing our human experiences, live parallel to us in different patterns, driven by different ambitions. They are the bearers of a beauty that transcends and overflows—a beauty that speaks only to them of the deepest mysteries, whose true essence remains hidden from most.

Amongst these, as custodians and interpreters of beauty and mystery, we find the great artists, especially those of the past, whose memory endures because their art continues to keep them alive and present today.

These are extraordinary men whose vision of reality was so powerful that it continues to speak through their refined works, capable of transforming the lives of those who gaze upon them and shaping the artistic journey of those who came after.

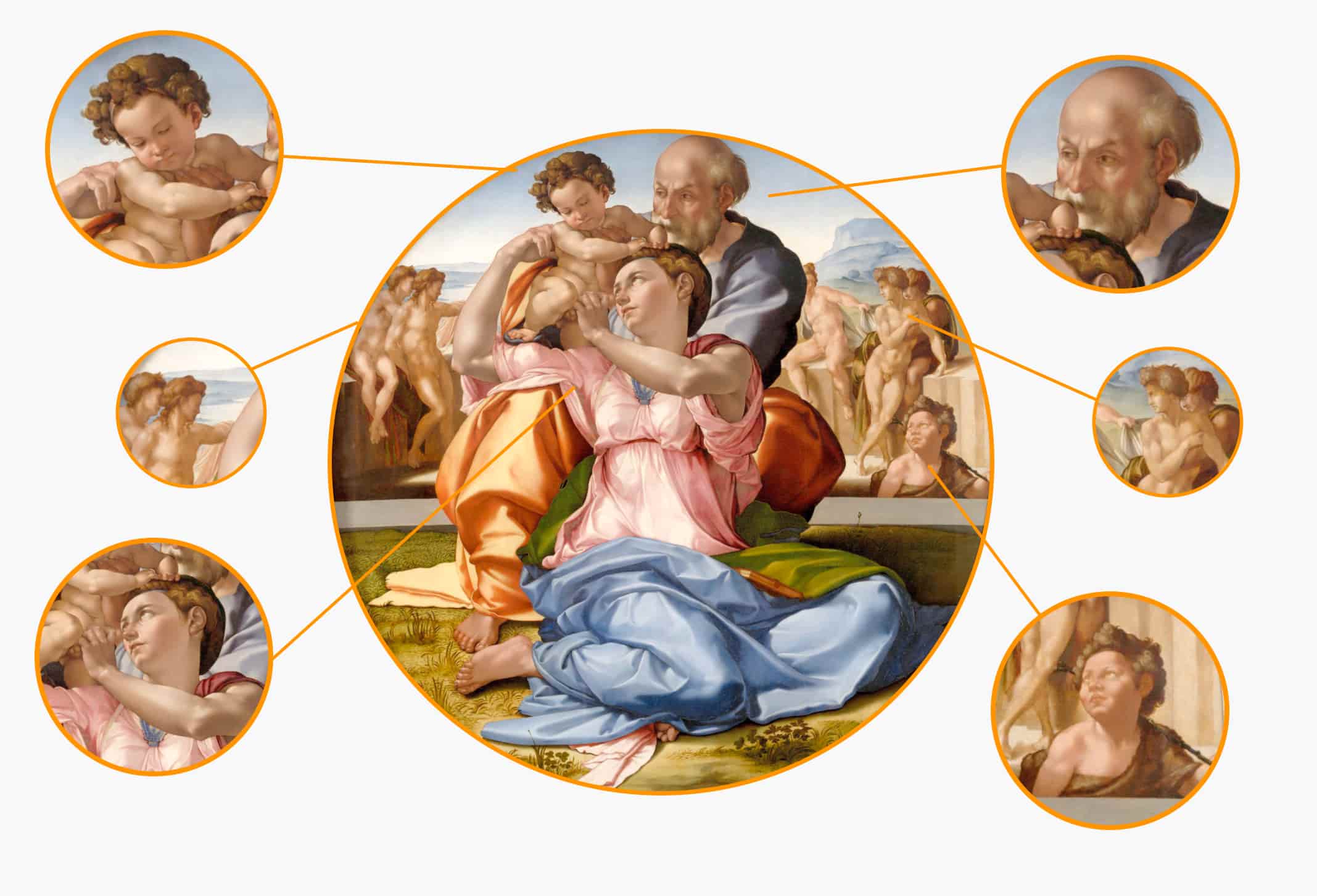

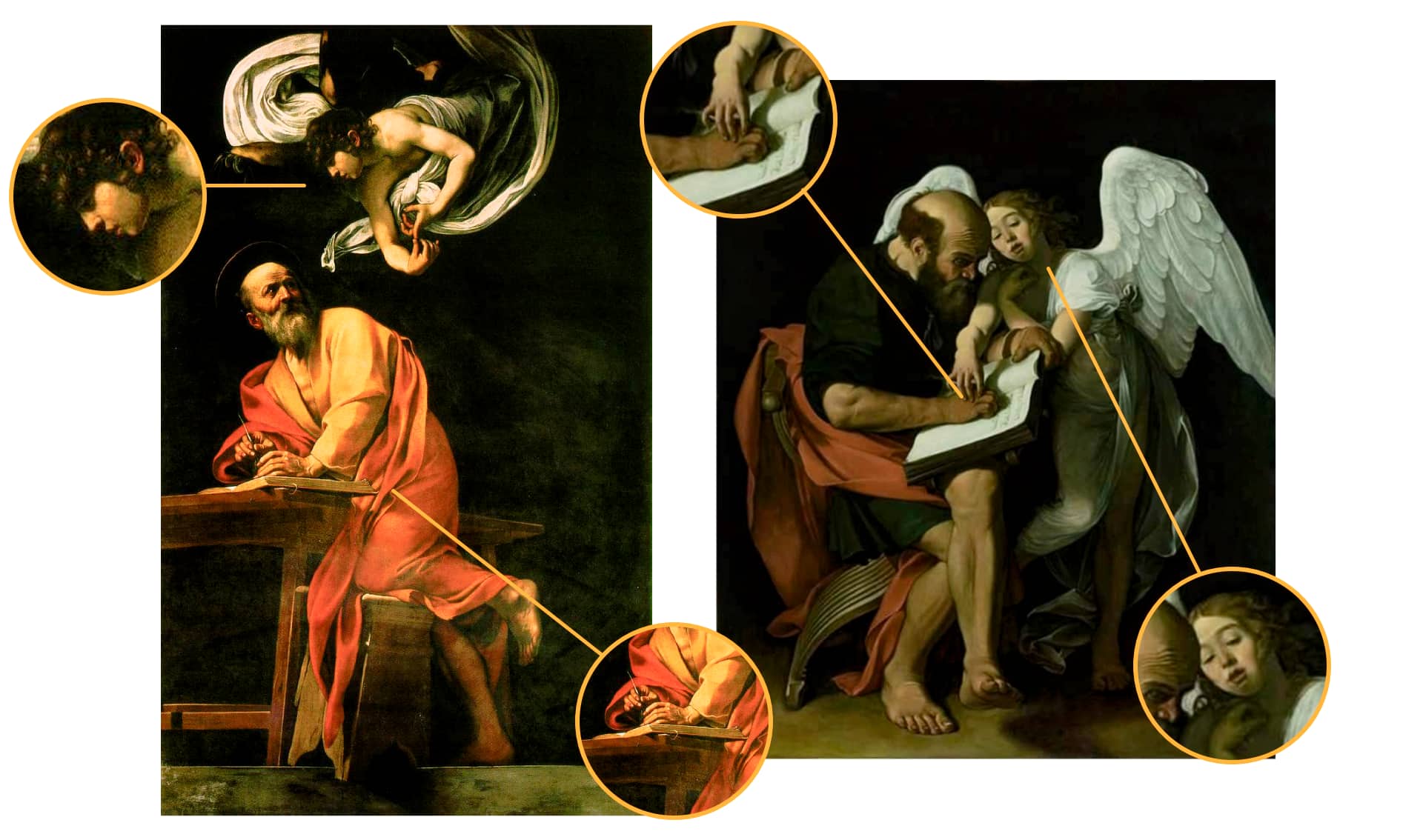

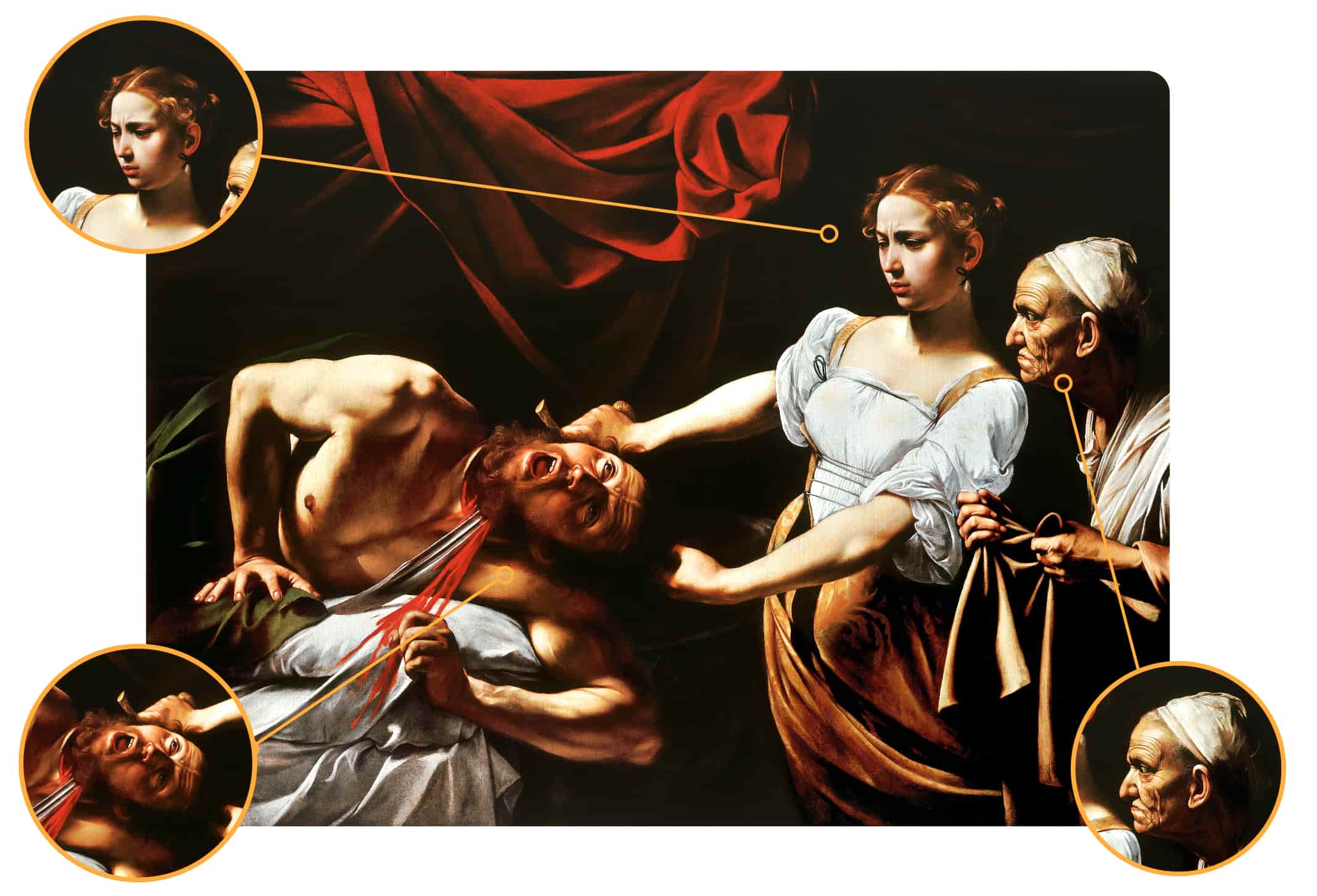

Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raphael are clear examples: countless artists followed in their footsteps. And then there was the other great Michelangelo, known to the world as Caravaggio, whose genius inspired an entire generation of painters, the Caravaggisti, who carried his revolutionary vision forward.

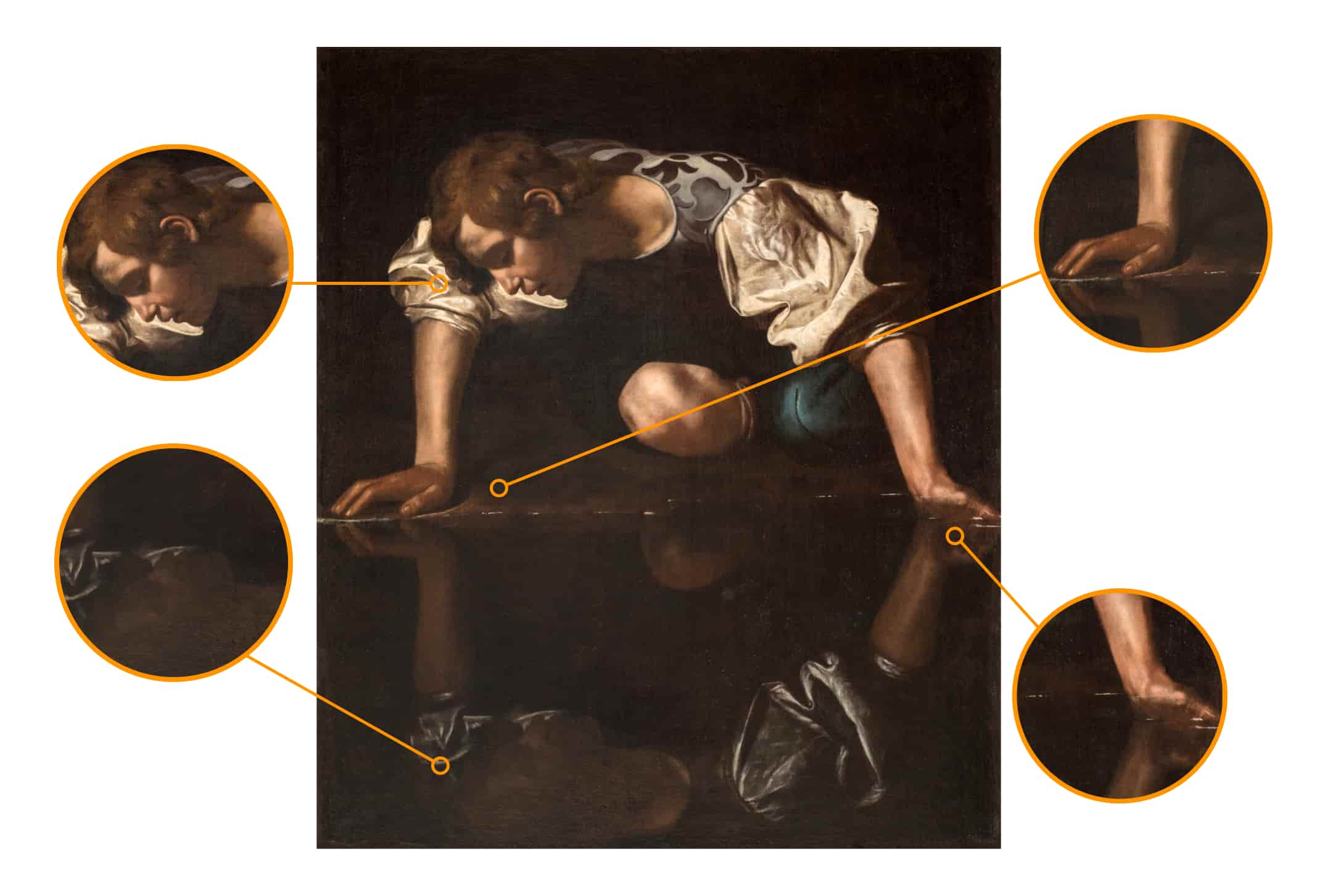

The painting I wish to discuss possesses a story as nebulous, controversial and fascinating as that of Caravaggio himself, to whom it has often been attributed: Narcissus. The complexity of this work’s history lies not so much in its aesthetic perception, since it can hardly fail to inspire admiration, but in the critical debate surrounding it.

Scholars and art historians, especially in more recent times, have examined and re-examined the canvas, yet the question of authorship remains unresolved.

Since its rediscovery in 1913 within a private collection, Narcissus has captivated the attention of art historians, who, particularly in the early years following its unveiling, were inclined to attribute it to Caravaggio, following the intuition of the great art historian Roberto Longhi.

Indeed, the painting lends itself convincingly to such a hypothesis. tThe interplay of light and shadow, the textures of the garments and especially the folds of Narcissus’s shirt, all point toward a Caravaggesque hand. These stylistic elements also suggest a possible dating between 1597 and 1599.

However, more recent scholarship has proposed alternative authors and dates. Amongst the various hypotheses, the attribution to Orazio Gentileschi seems the least plausible. A far more convincing proposal is that of Giovanni Antonio Galli, better known as Lo Spadarino, which would place the work in the mid-seventeenth century.

This attribution is supported by the evident similarities between the figure of Narcissus and that of Ganymede in The Banquet of the Gods, a work unquestionably by Spadarino. When one compares the two figures—their torsion, proportions, and treatment of light—they align almost perfectly, even sharing a similar application of pigment.

The fact that Narcissus’s face is only partially visible, and thus lacks the dramatic expressiveness typical of Caravaggio’s figures, makes a definitive attribution all the more difficult.

It is, indeed, hard to bring such a debate to an end. Yet one thing remains certain: the very persistence of this discussion proves that, regardless of its author, this painting could only exist because Caravaggio transformed the course of art history. He created not merely a new way of painting, but an entirely new way of seeing, of constructing and understanding a scene.

Thus, the question is not who painted the work, but why it exists. Without Merisi, Narcissus would not have taken this form; its conception and its essence are indebted to his radical vision.

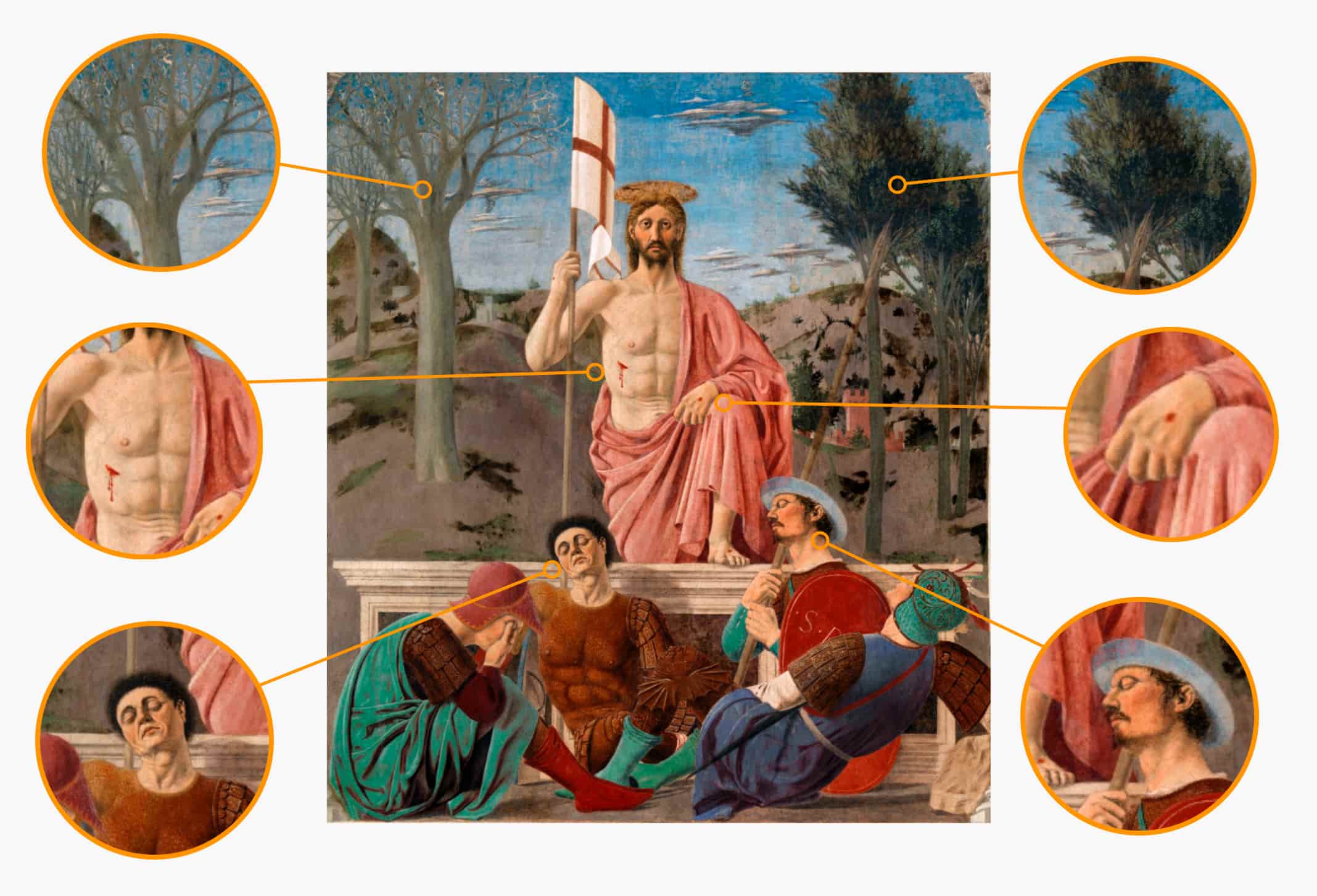

The very interpretation of an intense drama such as that of Narcissus, as told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, stripped of every superfluous iconographic element in order to reveal its essence, would have been unthinkable without Caravaggio’s bold example.

Whoever painted this canvas began, of course, with the myth itself—but eliminated all its traditional attributes: the figure of Echo, the rejected suitors, the wooded setting where most of the episodes unfold and the deer that Narcissus hunts. What remains is the distilled essence of the myth—the pivotal moment of self-discovery.

As so often happens, the revelation of truth becomes the source of tragedy, for truth exposes our fragility. Before it, we are left naked—revealed for what we are, not for what we wish to be. In that instant, our perception of ourselves and of others collapses.

Here, the story of Narcissus is expressed not through his legendary beauty, the cause of others’ desire, but through the fulfillment of the prophecy that defines his fate because one cannot escape destiny.

The seer Tiresias had foretold to the nymph Liriope, Narcissus’s mother, that her son would live a long life only if he never came to know himself. After scorning the love of many, as divine punishment, Narcissus one day gazed into the clear waters of a spring—and in that reflection, came to know himself.

In that instant of recognition, the prophecy was fulfilled. According to classical tradition, Narcissus fell in love with his own image, condemned to an unrequited passion for himself, a love he had denied to others.

Unable to part from his reflection, he wasted away, and from his body sprang the flower that bears his name.

Ovid tells us that Narcissus died of hunger and sorrow; yet here, the moment of death is portrayed differently—shaped by Tiresias’s prophecy.

Narcissus seems to reach for the object of his love, seeking contact. But the touch is impossible. His pose—the bent leg, the tension of the arm pressing downward—foreshadows his impending fall into the water, where he will not find love returned, but death.

His left arm is already partially submerged in the calm, clear surface: the tragedy is imminent, though rendered without the overt dramatism often used to depict youthful death.

The perfect symmetry of the composition is reinforced by the varied tones and intensities of the same colours, softer in the realm of reality, where Narcissus kneels, deeper and more saturated in the water, the essential element through which his destiny unfolds.

The perfection of the design narrates and embodies the illusion of an unfulfilled love—a vain, futile and unreal passion defined by an all-consuming self-adoration.

In this obsessive exaltation of the self, perception of reality dissolves, and love transforms into death.