Michelangelo's Saint Matthew and the beauty of the unfinished

In the sculptural figure of Saint Matthew, Michelangelo Buonarroti reveals a radical vision of art, one in which beauty lies not in polish or completion, but in the struggle of form emerging from raw matter.

I have always been fascinated by completed, defined, finished art — the kind that allows me to reflect, to search for the countless messages hidden within it through small details that are only apparently accidental.

It is as if every work from the past represents a refined intellectual game, whose true purpose is not merely to convey beauty, but rather to share its deeper meaning and inspiration, to be sought and read precisely in the colours and forms that are projections of the artists’ thoughts and souls.

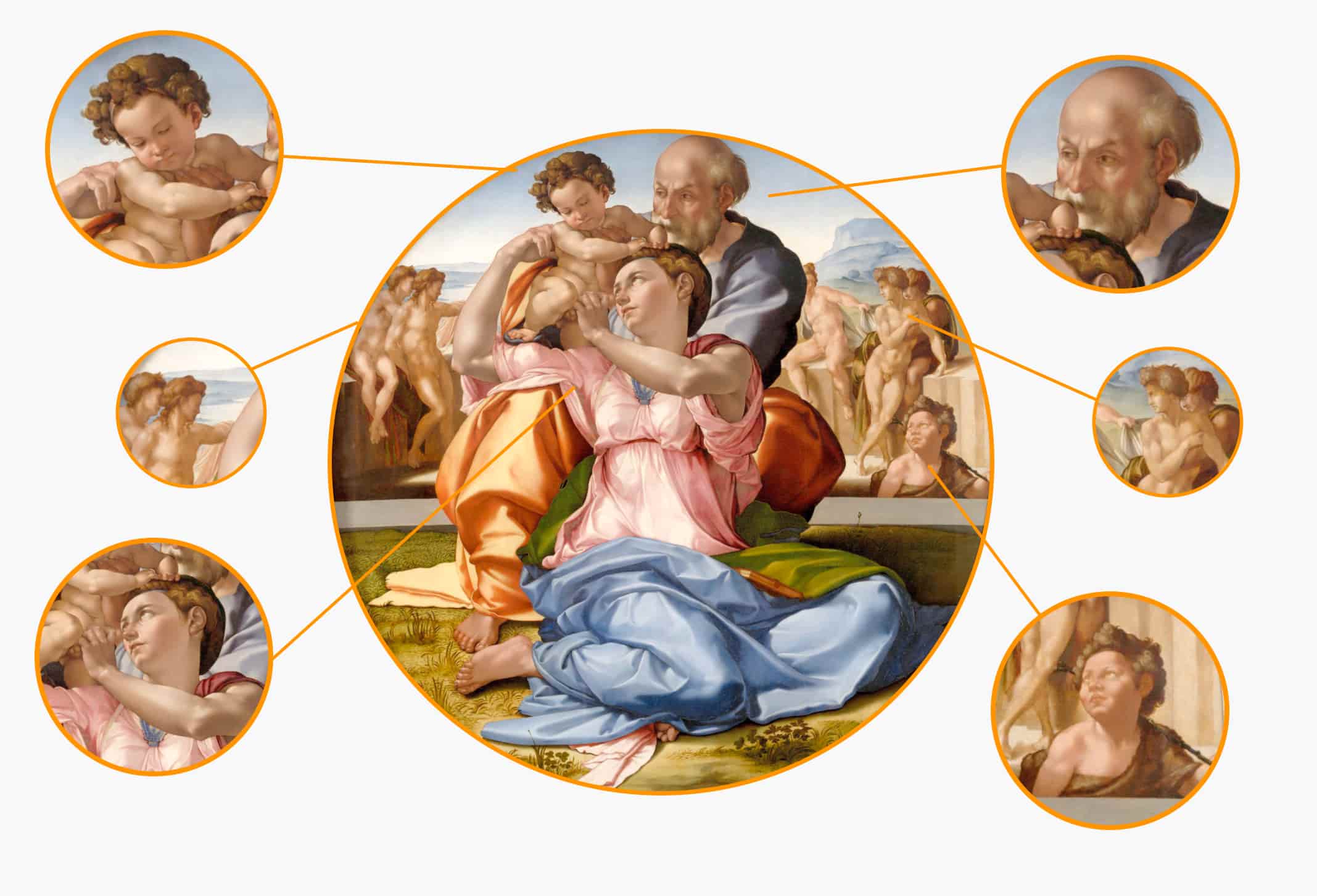

Many of these messages are undoubtedly contained in the works of Michelangelo Buonarroti, whose genius was able to range across every artistic and cultural field of his time. The artist’s philosophical training meant that, more than others, he felt the need to hide symbols rich in meaning within his many works of art.

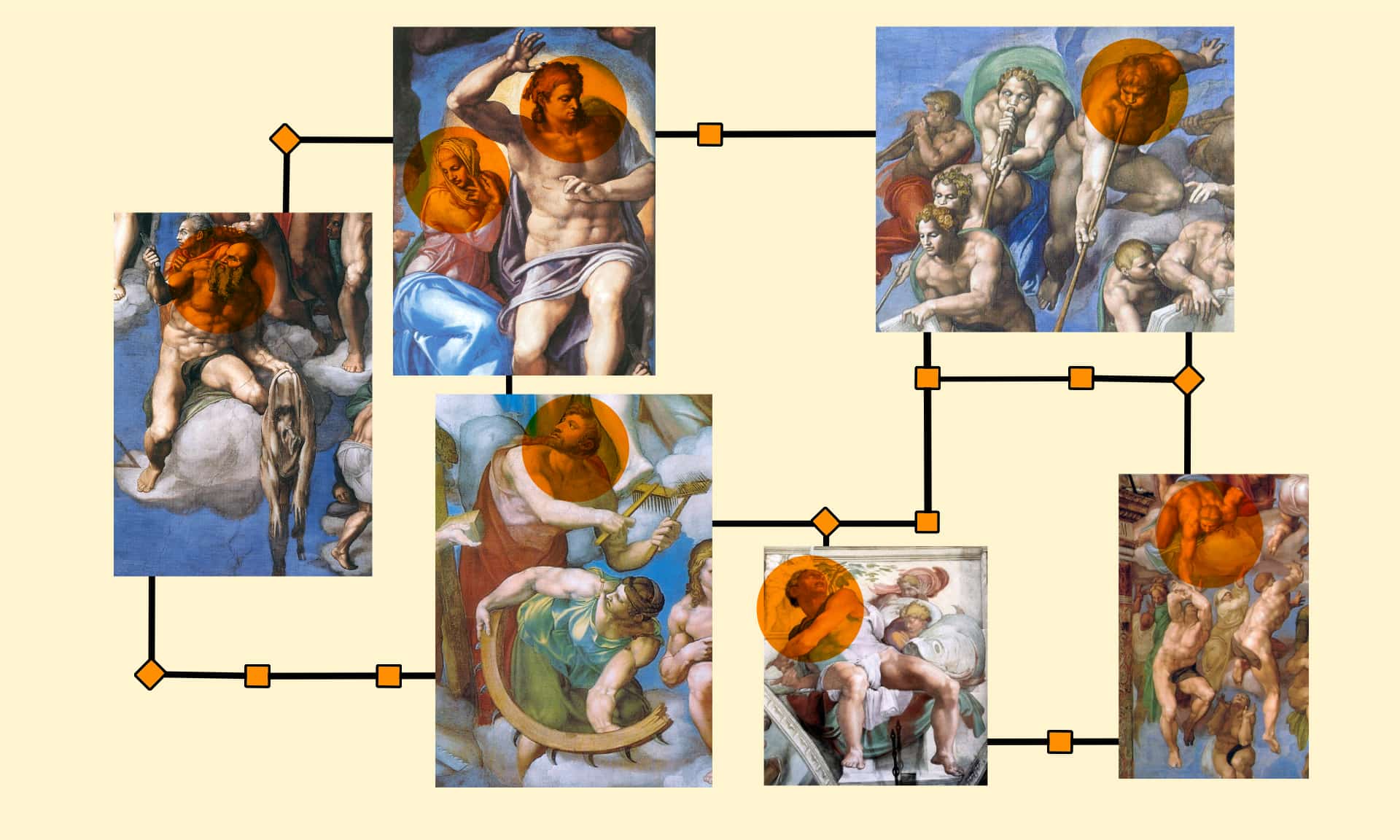

A perfect example is the Sistine Chapel: on its frescoed walls, beauty seems to be the dominant element, yet within so much evident beauty lie complex symbols and images, ready to reveal and narrate messages to those who are able to look beyond the fleeting appearance of outward form.

Despite the evident intellectual richness of every painted work by Michelangelo, I find that many elements to be identified and deciphered should instead be sought within his sculptures, whose perfection of form clearly testifies to a perfection of thought and culture.

Many of the artist’s sculptural works, in fact, bear learned references drawn from writers, philosophers and scientists. Each sculpture tells of inspiration and mastery, but above all of Michelangelo’s vision of art, matter and the life concealed and contained within it.

In 1506, two years after completing his famous David, Buonarroti created a sculptural work whose marvelous unfinished quality not only reflects and anticipates his later artistic evolution, but also expresses his search for and vision of every form already inherent in raw matter — matter that others perceived merely as a shapeless mass.

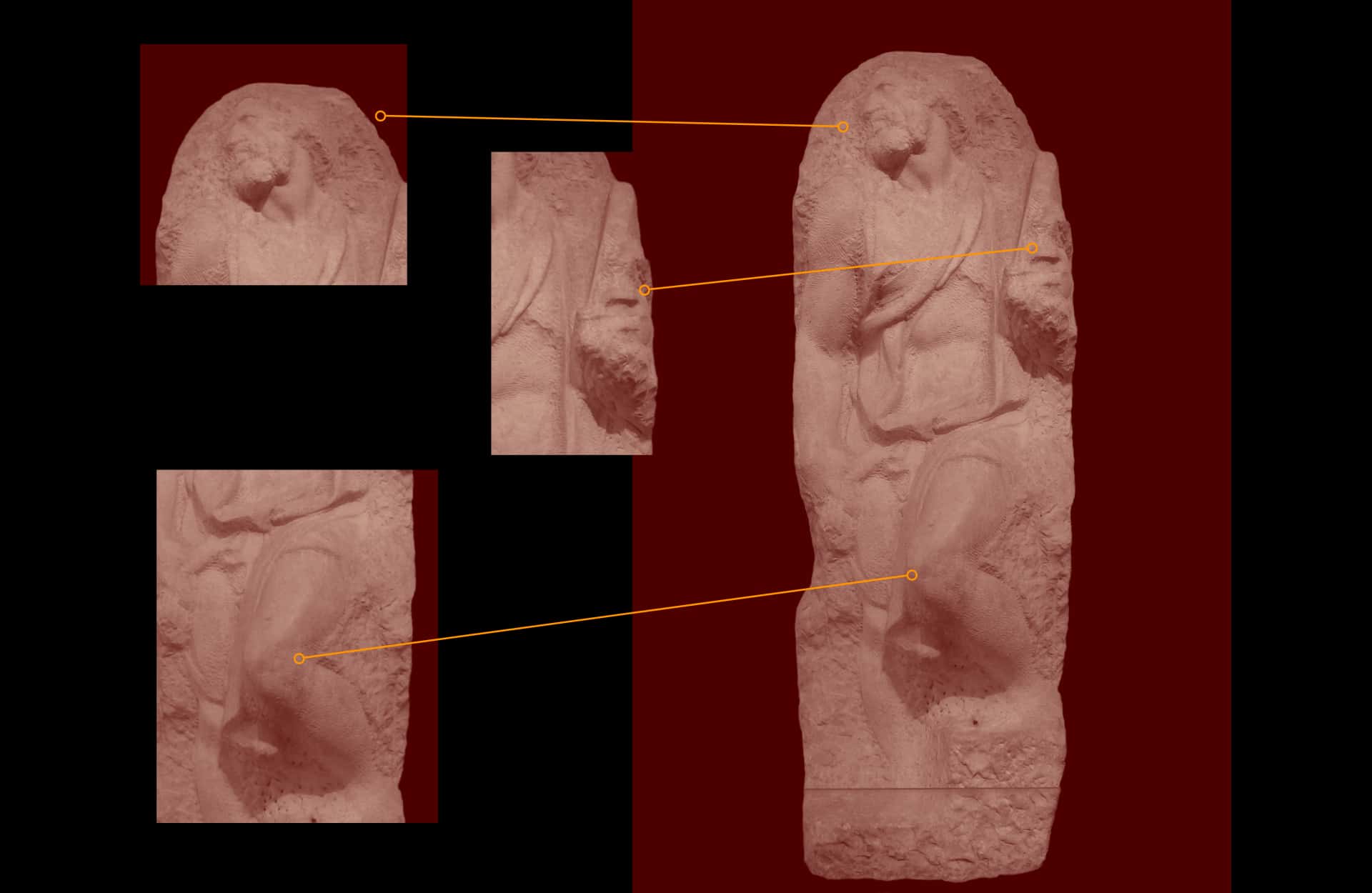

I am referring to Saint Matthew, the only one of twelve sculptures commissioned to him as pillars for the dome of Florence Cathedral. Michelangelo never finished the work because he had to leave for Rome. In light of this historical fact, Saint Matthew might appear to be simply an unfinished piece due to lack of time, yet what it truly reveals is a radical transformation in the very conception of sculpture.

While in the David beauty takes shape through attention to detail, in Saint Matthew true beauty lies precisely in the lack of definition and polished surfaces.

The physical and inner tension of David, which foreshadows an act of strength about to occur but not yet in motion, gives way to a force already expressed and enacted by the figure of Matthew, who emerges from the marble, depicted at the very moment of freeing himself from the matter that imprisoned him.

This moment concretely embodies the artist’s belief that sculpture is the art of subtraction, of seeking the form already expressed and complete within the material itself. Despite the lack of refinement and finish in the apostle’s figure, the image conveys not only a perception of matter, but also Michelangelo’s deep knowledge and admiration for classical art.

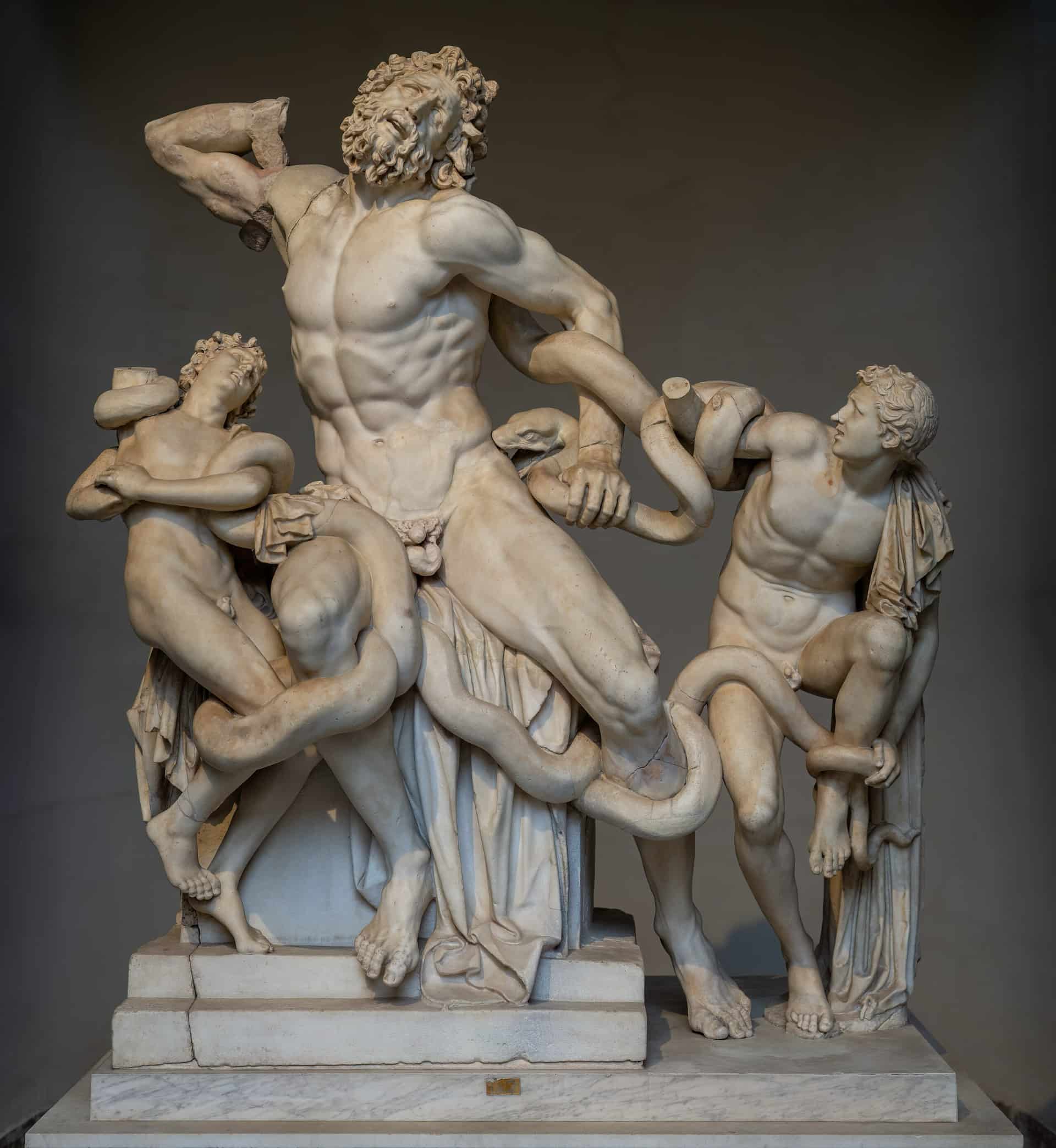

The twisting motion of the emerging figure is in fact a learned reference that clearly recalls the pose of the Laocoön, the marble group discovered in 1506 and admired by Michelangelo in that same year.

The statue of Matthew was worked only on the front; the back is still held within the marble that contains it. The apostle’s body displays all its power, all its force, in the act of freeing itself and rising upward.

A simple step, at the lower left of the figure, serves a technical purpose, as it allows the evangelist to bend his left leg and gain the necessary momentum to emerge. This architectural element also functions as a lever for the left leg, which appears flexed, while the right arm is perfectly extended, enabling Michelangelo to apply the balance typical of the so-called contrapposto pose.

Even in its unfinished state, the statue clearly presents the identifying attribute of Matthew: the apostle holds his Gospel in his left hand, further emphasizing the sense of movement expressed almost exclusively on that side.

The head, instead, is turned to the right, thus breaking the rigid and predictable frontal view of the statue. The drapery of the garment defines and highlights Matthew’s tense muscles, in keeping with the characteristics of almost all the figures in Michelangelo’s extraordinary works.

The dramatic sense of expectation, of beginning and ending, expressed in all of Michelangelo’s unfinished — but by no means incomplete — sculptures would later find its highest expression in the final work created by the artist for his own tomb: the Rondanini Pietà.

In this piece, where the fusion of bodies conveys the dramatic and multifaceted reality of pain, it is clear that although Michelangelo’s physical strength had waned, he had never ceased his personal search for form, and above all for the messages that the creative spirit had hidden within matter itself.