Iran is once again convulsed by mass protest. What is unfolding, however, cannot be understood as a single moment of unrest or a spontaneous eruption of anger. It is the accumulated result of years of social exhaustion, political foreclosure and economic suffocation, intensified by sanctions, war and authoritarian misrule.

The crowds in the streets are responding not only to a collapsing currency or the price of bread, but to the deeper realisation that life has become structurally unliveable and that no meaningful avenue exists through which to shape the future.

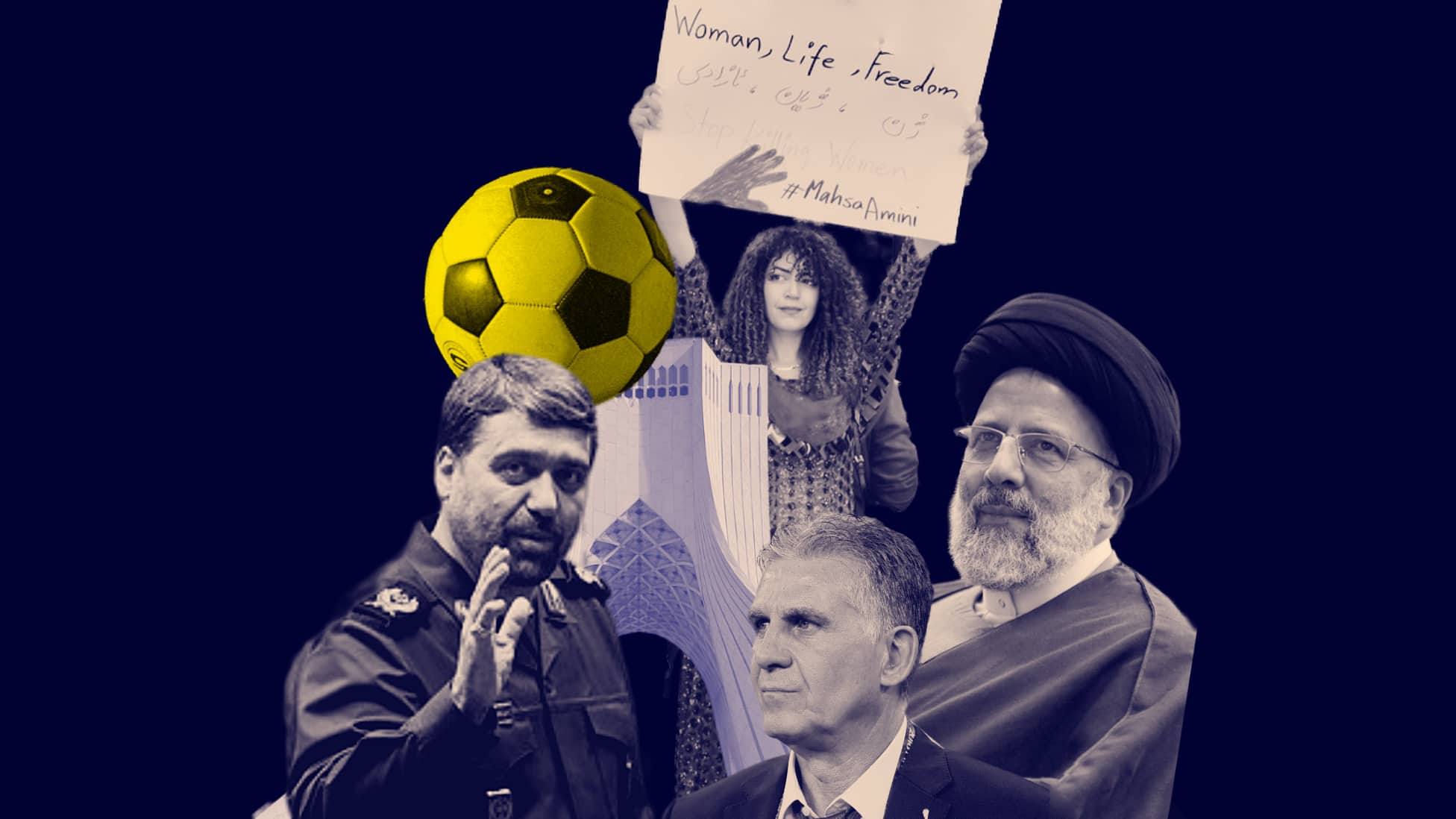

Protest has long been woven into the fabric of political life in Iran. Since the nationwide uprisings of 2017–18, it has taken on a new rhythm, cyclical, geographically expansive and increasingly politicised. Each wave has had its own immediate spark, fuel prices, water shortages, police violence, the killing of Mahsa Amini. Yet all have drawn from the same reservoir of grievance.

Rural and provincial poverty has deepened dramatically, inequality has become grotesque and corruption is openly flaunted. Inflation has hollowed out everyday life, with food prices surging, with over 70% increase in food inflation and over 110% inflation in the cost of bread. For many, survival itself has become precarious. Under such conditions, an economic protest rarely remains economic for long.

The current unrest began in the bazaars, first among electronics traders and then in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, before spreading rapidly to provincial towns and cities. What followed was not a narrow labour dispute but a challenge to the system itself and those who benefit from it.

When demonstrations returned to the capital in force, the state appeared visibly disoriented. Thousands have been arrested, dozens killed and internet blackouts imposed. Yet the protests have continued to cut across class and geography, drawing in the urban middle class as well as the very poor in peripheral regions. They are bound less by politics than by fatigue.

This exhaustion has been produced by design. Politically, the Islamic Republic is a system in which popular sovereignty is tightly managed and systematically diluted. Ultimate authority rests with the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, while elected institutions operate within narrow boundaries enforced by unelected bodies.

Since the end of the Iran–Iraq war, an authoritarian neoliberal order has taken shape, marked by privatisation without accountability, the erosion of welfare and the rise of quasi-state conglomerates that dispense patronage rather than justice. Healthcare and education have been commodified, social mobility narrowed and public trust steadily corroded. Independent unions have been crushed, civic mediation dismantled and dissent rendered synonymous with threat.

Repression, however, has not been total. The 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom uprising forced tangible changes on the ground. In many cities, women now move through public space without the mandatory hijab, a significant gain won through collective defiance. Political discussion, while still constrained, has widened slightly. These were not reforms offered in good faith, but defensive retreats by a regime acutely aware of its own fragility. They remain precarious, but they matter precisely because they were taken from below, not granted from above.

However, Iran’s internal political order is shaped as much by external pressure as by domestic control. Sanctions, particularly those imposed under Barack Obama and intensified under Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign, have devastated Iran’s economy while entrenching elite control. They have strengthened black markets, empowered parastatal networks and rewarded those closest to power, while ordinary people absorb the inflationary shock. To deny the role of sanctions is dishonest, and to use them as an alibi for domestic failure is equally cynical. The lived reality is that imperial pressure and internal authoritarianism have fused, producing an economy that enriches a narrow oligarchy while grinding down society.

Yet the Islamic Republic did not merely survive this pressure, it justified itself through it. The regime’s durability rests on a founding promise forged in opposition to foreign domination. The 1979 revolution was not only a revolt against monarchy, but against a longer history of hollow sovereignty, crystallised in the 1953 coup backed by Britain and the United States. Across ideological lines, the Shah came to symbolise subordination to imperial power. The Islamic Republic’s core claim to legitimacy was that it restored independence after decades of humiliation.

That narrative once mobilised society. Today, it disciplines it. The promise of independence has curdled into isolation, corruption and immiseration. A state that claimed to defend the nation against imperial domination increasingly appears unable, or unwilling, to defend its own population from hunger and precarity. Anti-imperial language remains, but its emancipatory content has drained away.

When ideological promises collapse without being replaced, a vacuum opens. The Iranian Revolution is often imagined as a clean rupture between monarchy and theocracy. In reality, it marked a reconfiguration of power rather than its dismantling. The Pahlavi state imposed a top-down nationalism rooted in a narrow, Persian-centric vision, marginalising clerical authority and suppressing ethnic diversity. The Islamic Republic rejected that language only to replace it with an equally absolutist framework, subordinating belonging to ideological conformity and reframing dissent as heresy. Across both eras, civic life was steadily dismantled. When identity is suppressed for decades, it does not disappear. It returns under strain, often in distorted form.

And then “restoration” becomes the solution…

Today, both inside Iran and across the diaspora, national identity is resurfacing in reactive forms, shaped by nostalgia, emotion and exclusion. The Pahlavi period is being reimagined as an era of dignity and order, stripped of its repression, inequality and dependence on foreign power. Historical accuracy matters less than psychological repair. Restoration, rather than transformation, becomes the imagined solution.

It is in this context that Reza Pahlavi has re-entered the foreground. The son of the deposed Shah, he declared himself crown prince in exile after his father’s death in 1980 and has remained largely marginal to Iranian politics ever since. More recently, he has sought to recast himself as a “transitional” figure, issuing calls to action from abroad and benefiting from saturation coverage on exile media, most notably Iran International, a channel widely understood to reflect Israeli intelligence perspectives, particularly during Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Some protesters have chanted his name, alongside slogans such as “death to the dictator” and “long live the Shah”. This points less to a coherent monarchist project than to a desperation shaped by political paralysis. Nostalgia here functions less as endorsement than as symptom.

The limits of this restorationist current are stark. Pahlavi has no organised structure inside Iran, no grounding in the social movements driving the protests and no relationship to the lived realities of those risking their lives in the streets. His open alignment with Israel, an ethnocratic state that claims democratic legitimacy while practising apartheid and ethnic cleansing, and whose leadership now faces pursuit by the world’s highest criminal court, deepens suspicion rather than trust. Among Iranian monarchists, however, Israel is admired for different reasons. It is not valued as a democratic model, but as an aesthetic of force: military dominance, impunity and unwavering Western backing, even while sadistically suppressing an indigenous population.

The United States, meanwhile, remains characteristically opportunistic. While rhetorically supportive of “the Iranian people”, its record suggests a preference for stability, pliability and access to resources over genuine democratic transformation. The lesson of places such as Venezuela is not that Washington backs popular sovereignty, but that it favours insiders prepared to ensure continuity by offering strategic resources on terms overwhelmingly favourable to empire. None of this aligns with the aspirations of those protesting over hunger, dignity and exclusion.

Democracy requires structures capable of holding contradiction

Crucially, any imagined future that depends on erasure is doomed from the outset. Iran will remain a society with a significant Islamic population, regardless of whether restorationists welcome this reality or not. A democratic future cannot be built on the fantasy of purging religion from public life any more than it can be built on clerical domination. Projects that define belonging narrowly, whether in religious, civilisational or ethnonational terms, reproduce the very authoritarianism they claim to oppose. Democracy requires structures capable of holding contradiction, difference and conflict without coercion.

Foreign powers will undoubtedly seek to exploit Iran’s crisis. Intelligence operations are a constant presence and the threat of renewed regional conflict hangs over the country. But the Islamic Republic’s reflexive habit of blaming all dissent on external enemies now rings hollow. Responsibility for this moment lies first and foremost with a state that has combined repression, corruption and economic mismanagement for decades and now finds its founding promise collapsing under the weight of its own failures.

The people in Iran’s streets today are confronting real deprivation and exclusion, demanding a life with dignity and a voice in shaping their future.

A politics that offers them only crowns, clerics or custodians will fail them equally. What is at stake is the creation of democratic structures capable of holding difference without repression, structures that neither empire nor nostalgia can supply.

Anything less will merely reproduce the disease under a different name.