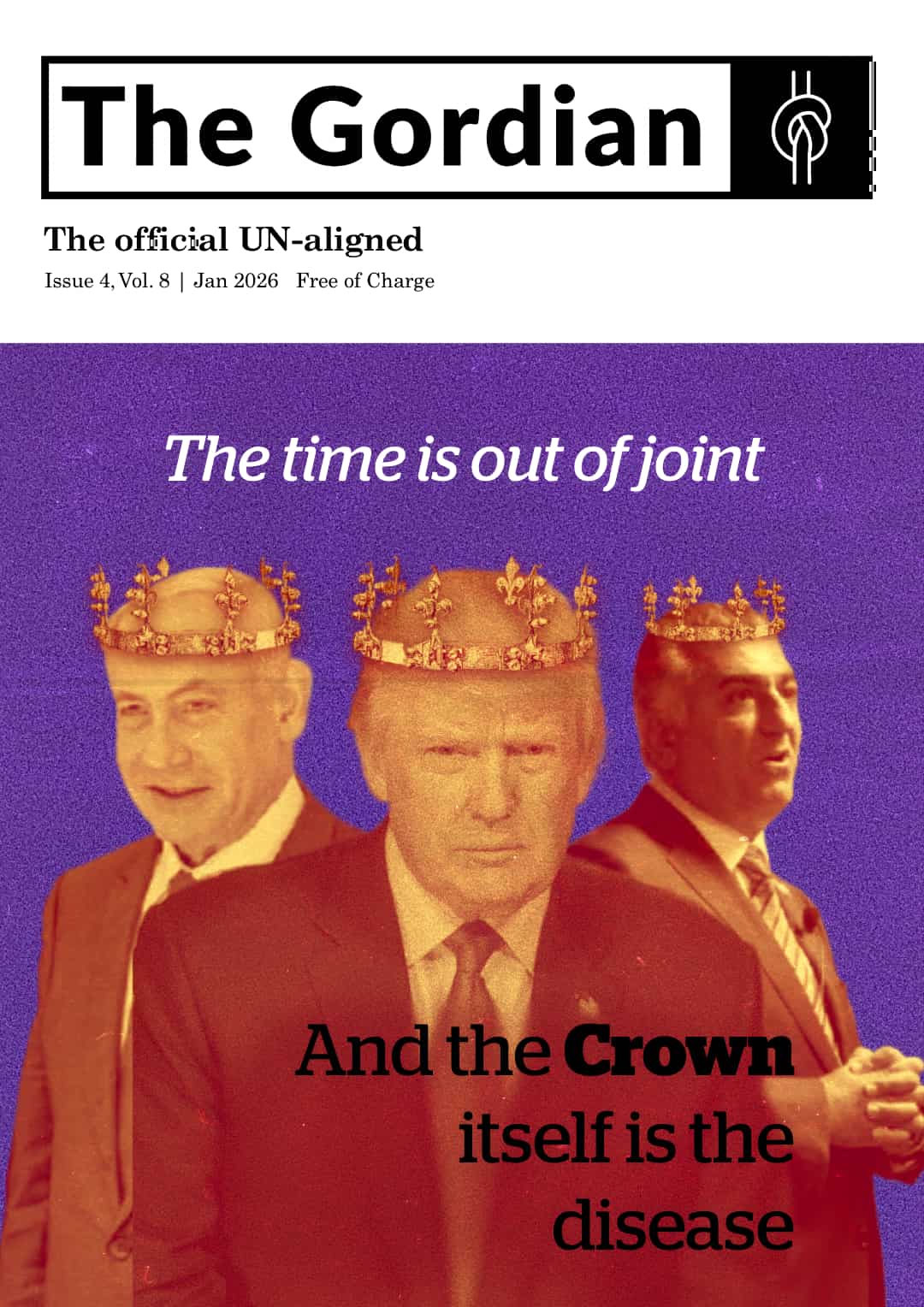

A world of paper promises: The betrayal of women from Gaza to Sudan

International agreements promised to protect them from violence, hunger, and inequality. But in the world's most brutal war zones, those promises are worthless, forcing millions of women to survive in a system designed to ignore them.

Life in the tumult of conflict is no life at all: surviving the immediate danger of shelling or gunfire only to be forced out of your home and community into unfamiliar, overcrowded places.

The danger has not passed. Food is harder to find, disease lurks around every corner and a new threat lives among you: those who seek every opportunity to sexually attack you, destroying your final shred of personhood.

Amidst the surgical ruination of their livelihoods, women are expected to muster up the strength to work and provide for their family.

But this expectation clashes with a wall of systemic barriers. A World Bank report on displacement cites a crushing combination of discrimination, lack of social networks, language problems and the devastating impacts of forced displacement on women’s physical health and socio-emotional well-being.

If they can find work, it’s beyond demanding for menial pay; they and their children will still go hungry.

They skip meals, though few and far between. They care for children, who themselves are constantly hungry and dealing with pain beyond their comprehension. They navigate unceasing political instability and normalised sexual violence.

This is all while following the inequitable walk of life that the institutions of this world created for them.

Health in focus

Even in 2025—a time when the world seems consumed by health and wellness—millions of women and girls are experiencing worsening health due to deepening food and nutrition crises in conflict-affected regions.

Globally, in 2024, the Food Security Information Network (FSIN) reported that 295.3 million people, 22% of the analysed population, faced high levels of acute food insecurity across 53 countries.

The 2025 outlook from the same report is even bleaker. In the 26 territories experiencing nutrition crises, an estimated 37.7 million children aged six months to five years suffered from acute malnutrition, with Sudan, Yemen, Mali and the Gaza Strip facing the most severe crises.

The impact on mothers and infants is particularly severe.

Between 2012 and 2023, rates of anaemia in women and girls in Africa steadily increased. Acute malnutrition among pregnant and breastfeeding women rose by 25% from 2020 to 2022 across 12 hardest-hit countries, including Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, Mali and Yemen.

In 2024, FSIN estimated that 10.9 million nursing mothers in 21 countries were malnourished. Their children face a higher risk of illness, undernutrition and death, with physical and cognitive consequences that are lifelong and visible early in stunted and wasted bodies.

The psychological toll is equally severe. Exposure to violence, family disruption and confinement in displacement camps produces some of the world’s highest rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety.

In conflict environments, women are often the backbones of their families: caregivers, gatherers, providers. An inability to find work in such dire circumstances increases the element of despair – something that sexual predators delight in.

AP News recently released a piece about an unnamed woman in Gaza who, struggling to keep her husband’s business afloat, turned to a man promising a contract as an aid worker. After being lured and physically trapped, she was forced to comply with the man’s sexual demands before being allowed to leave. She fearfully recounted, “I had to play along because I was scared, I wanted out of this place.” For the price of her bodily autonomy, she received a meager sum of money and a few supplies. There was no aid worker job.

Such stories are far from rare. In Sudan, sexual violence has been normalised by both sides of the war. Women living in war-torn Omdurman have spoken to the Guardian about the widespread practice of exchanging sex for food. And this is not a one-time occurrence; those who refused or stopped having sex with soldiers have described being tortured in retaliation.

A resident in west Omdurman described how soldiers use abandoned homes, making women “come and queue outside our neighbourhood” before selecting them. The soldiers then “choose those they like the look of to enter houses,” he explained. “I sometimes hear screaming but what can you do? Nothing.”

Even if they can escape the warzone, there is nothing guaranteeing women’s safety in a displacement setting. In 2023, 42 women in Nigeria were kidnapped outside of a displacement camp by Boko Haram insurgents while gathering firewood in exchange for ransom. Since the start of the Boko Haram insurgency in 2009, approximately 8,000 women, including many children - boys as well as girls - have been abducted in Nigeria.

In Haiti, kidnapping for ransom is also essential revenue source for armed forces. In 2022, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, published a damning report on how women and girls in Haiti are publicly violated as a tactic for gangs to demonstrate their authority and force compliance. In some instances, the report notes, the kidnappers use recorded videos of the rapes to press the parents or other family members to pay the ransoms.

Each day that conflicts persist, women and girls remain trapped in this cruel cycle. This isn’t life—it’s a suffocating fate the world allows them to endure.

International (in)action

The rights of these women are theoretically guaranteed by a web of international commitments, from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) to the African Union’s 2003 protocol on women’s rights.

Yet this architecture of rights crumbles upon contact with reality. Nations like Sudan, Ethiopia and Yemen are signatories to these very treaties, even as they preside over some of the world’s worst violations.

The fundamental flaw is not in the principles, but in their deliberate toothlessness. These conventions are there to measure, true, but they were designed without mechanisms to compel accountability. They have become mere tools to observe and report on inequality, not to enforce change.

This pattern of failure extends to the United Nations’ own Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Two goals in particular—SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality)—directly address the crises faced by these women.

However, as the 2030 deadline for achieving the SDGs looms, it is becoming increasingly clear that, far from making progress, the global community is actively regressing.

This systemic failure to enforce laws and meet goals has fostered a climate of total impunity. It is a climate that allows the horrors in Sudan and Haiti and has reached a devastating peak in Gaza, where Israel’s military assault has killed more than 28,000 women while starving an entire population—all without consequence.

Compounding this landscape of institutional collapse is a crisis of focus within modern feminism itself. While women in conflict zones endure these life-or-death struggles, much of the movement, particularly in the Global North, has become preoccupied with obscure culture wars, diverting energy and attention from where it is most needed.

A solution will not come easily. It is not enough to listen to women’s voices or include them symbolically in leadership. Conflict itself, and the impunity surrounding it, must be addressed first. Declarations and conventions cannot remain ceremonial; they must evolve into instruments of real protection.

Women and girls should never have to navigate such chaotic and uncertain lives. Yet today, they are left treading water—watching as those in the rescue boat debate the quality of the life preservers rather than throwing them.

They continue, against all odds, to keep their heads above water. And that resilience—the quiet persistence of women who refuse to sink—should be the world’s call to act, not merely to grieve. Because their survival should never depend on endurance alone.