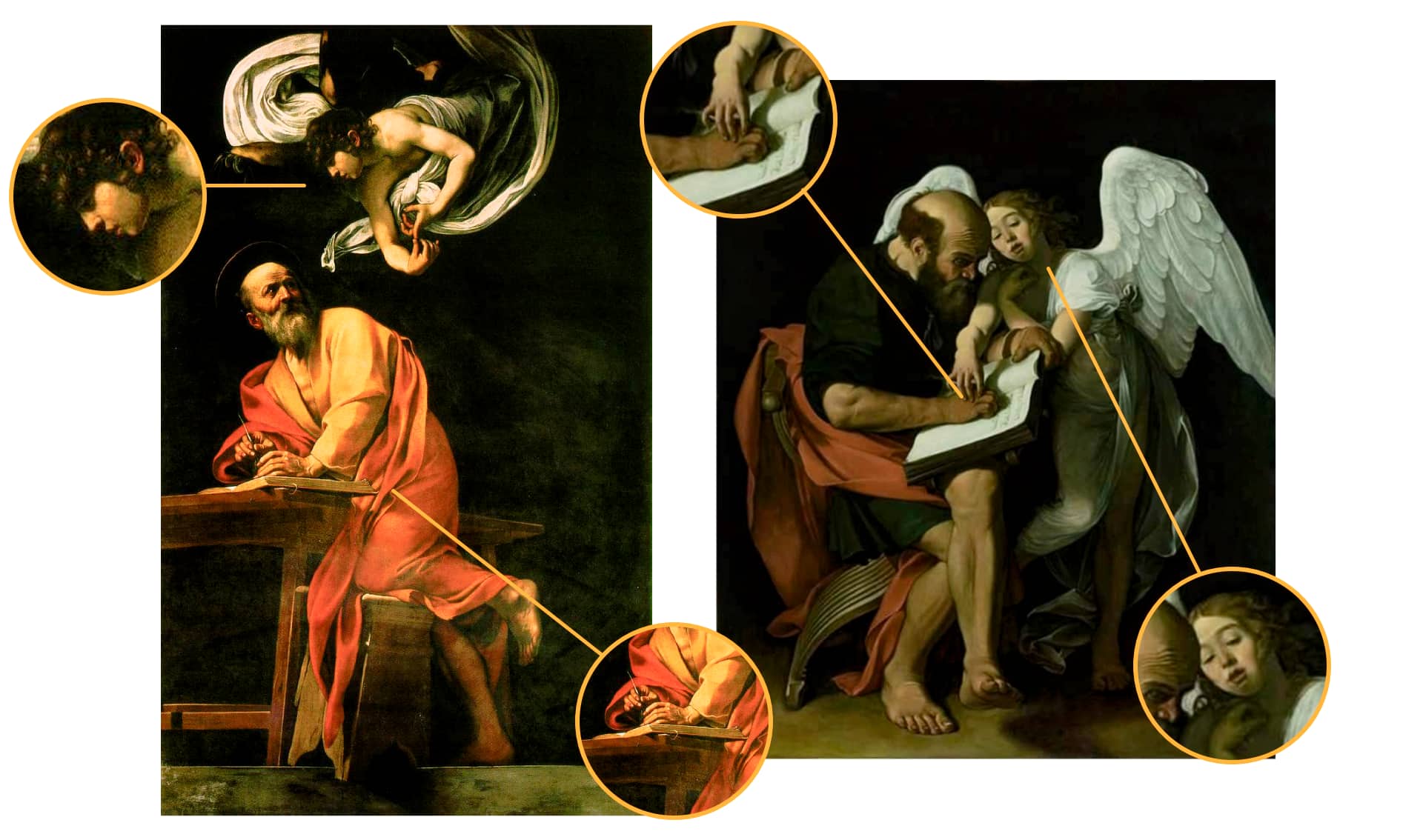

Caravaggio’s two Matthews: Realism rejected, revelation remade

Between 1600 and 1601, Caravaggio recast the scene: out went the coarse, patron-spurned Matthew and dominating angel; in came classical dress, a lighter touch and a writer in charge.

The Contarelli Chapel in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, preserves some of Caravaggio’s most celebrated works. Among them is the final version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, painted between 1600 and 1601. Yet before speaking of the painting we can still see, we must recall the one we cannot: the first version, now lost, rejected in its own day for being too unconventional, too starkly faithful to Caravaggio’s uncompromising realism.

That initial canvas showed Matthew—also known as Levi—not as a dignified saint, but as a simple, aging man of the people.

Dressed in a short tunic with a cloak around his waist, his legs and feet bare, the apostle sits awkwardly before a great notebook, transcribing his Gospel in Hebrew. His pose, especially the protruding feet turned toward the viewer and positioned directly above the altar, shocked the patrons.

The anatomical detail—the veins in his arm, the heavy hands—was masterful, but his coarse features and squat build clashed with expectations of saintly decorum.

Beside him, the angel was everything Matthew was not: graceful, refined, even sensual. With a flowing drapery and languid features reminiscent of Greco-Roman antiquity, the figure struck a dissonant chord.

More troubling still, the angel’s hand seemed to move Matthew’s directly, depriving him of any agency. The saint’s furrowed brow and shadowed face suggested not divine rapture but a man struggling under dictation.

What was missing, in the eyes of both patrons and public, was the sense of revelation—the divine message bestowed upon a worthy recipient.

Caravaggio’s intent, to underscore the weakness of man before God’s infinite wisdom, was clear but uncompromising, and it proved too much for contemporary taste. The painting was rejected, later passing into a Berlin collection, where it was destroyed in 1945.

Caravaggio returned to the subject with a second version, the one that survives today. The figures remain the same, but the conception is entirely different.

Here, the artist tempered his realism with a more idealized vision, in line with the expectations of his commissioners. Matthew is no longer bewildered or clumsy. His hand moves with autonomy, his expression focused. He is not simply a vessel for divine words, but an active, conscious participant in the writing of the Gospel.

The angel, meanwhile, is less imposing. His wings are smaller and more discreet, serving their symbolic purpose without overwhelming the scene. Where before he was pressed close to Matthew, here he hovers at a respectful distance, creating a dramatic but less intrusive entrance. The relationship between saint and angel is now one of collaboration rather than control.

Their garments, too, have been reimagined. Gone are the common clothes of the first Matthew and the diaphanous drapery of the angel. Instead, both figures wear attire and assume poses that recall the classical tradition so admired in Caravaggio’s time. The difference lies in color: the angel’s white drapery, as in many of Caravaggio’s works, symbolizes divine presence and eternity—truths that Matthew transmits through his Gospel.

Together, the two paintings—one lost, the other preserved—illustrate Caravaggio’s tension between his radical naturalism and the demands of his patrons. The first version reveals the artist’s uncompromising vision, the second his ability to channel that vision into forms acceptable to contemporary taste. In the dialogue between them, we glimpse both the daring honesty of Caravaggio’s art and the constraints under which it was created.