Art, music and leisure: American creativity in the early twentieth century

The early twentieth century brought a surge of American creativity as artists embraced abstraction, architects reshaped cities and cinema became a national passion, capturing both ambition and unease in a rapidly changing country.

In the early years of the 20th century, a group of American artists sought to capture the eclectic vitality and colour of urban life. This avant-garde movement, known as The Eight, laid the groundwork for a distinctly American artistic voice.

However, it was soon overshadowed by the arrival of modernism, following the groundbreaking Armory Show — an exhibition of modern European art held in New York City in 1913. Since the Civil War, French influence had dominated American sculpture, with bronze becoming a favoured medium among artists.

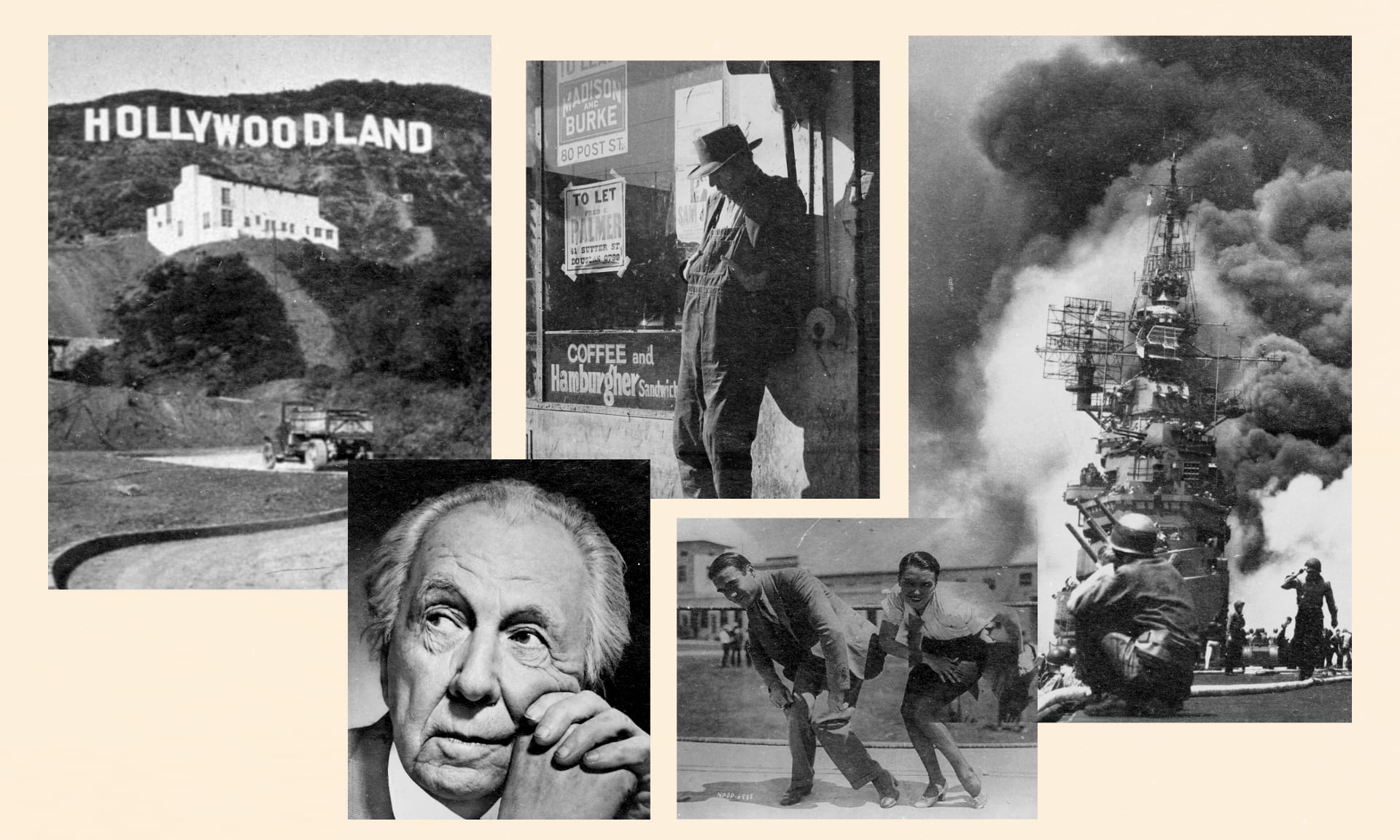

In the years following World War I (1914–1918), modern American art and architecture achieved international stature and recognition. Some architects began to explore modern, individual directions — most notably Frank Lloyd Wright, who pioneered organic architecture: a philosophy in which buildings harmonise with both their occupants and the natural environment.

Though critical of modern society, Wright became one of the most celebrated architects of the 20th century, admired for his ability to merge structure, purpose, and landscape into a cohesive whole.

By 1930, several German and Austrian architects introduced to the United States a design philosophy that emphasised the direct expression of function and structure. This approach, grounded in the principles of the Bauhaus school, evolved into what became known as the International Style, characterised by simplicity, abstraction, and the use of industrial materials.

Meanwhile, American painters working in Paris in the early 20th century experimented with abstraction through Cubism, a movement that represented objects as geometric forms. The cubes and planes replaced realism with an exploration of form and perception.

Pablo Picasso, one of the leaders of the movement, famously said, “Cubism is no different from any other school of painting… it is an art dealing primarily with forms.”

During the 1920s, many American painters turned their attention to scenes of rural life, depicting farms and small-town America. This localised focus evolved into a broader movement known as Regionalism.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, this artistic attention to social reality gave rise to Social Realism — a movement concerned with poverty, inequality, and the struggles of ordinary people. Artists employed under federal relief programmes were commissioned to create murals for public buildings, ensuring that art remained accessible to all, even in times of hardship.

In sculpture, academic styles continued to dominate in the first decade of the century. Initially marked by simplicity and directness, American sculpture later absorbed the influence of Cubist abstraction around 1916.

By the late 1930s, Constructivism, brought to the United States by émigrés from Germany, introduced a new concept: sculptures created from multiple manufactured elements rather than a single solid medium.

As for leisure, the most revolutionary pastime of the early 20th century was undoubtedly the cinema — or, as it was known then, the talking motion picture.

The first film made in Hollywood was D.W. Griffith’s In Old California, released on March 10, 1910. At the time, few believed in the future of film; The Independent newspaper wrote a week later, “It is probable that the fad will die out in the next few years.” They could not have been more mistaken.

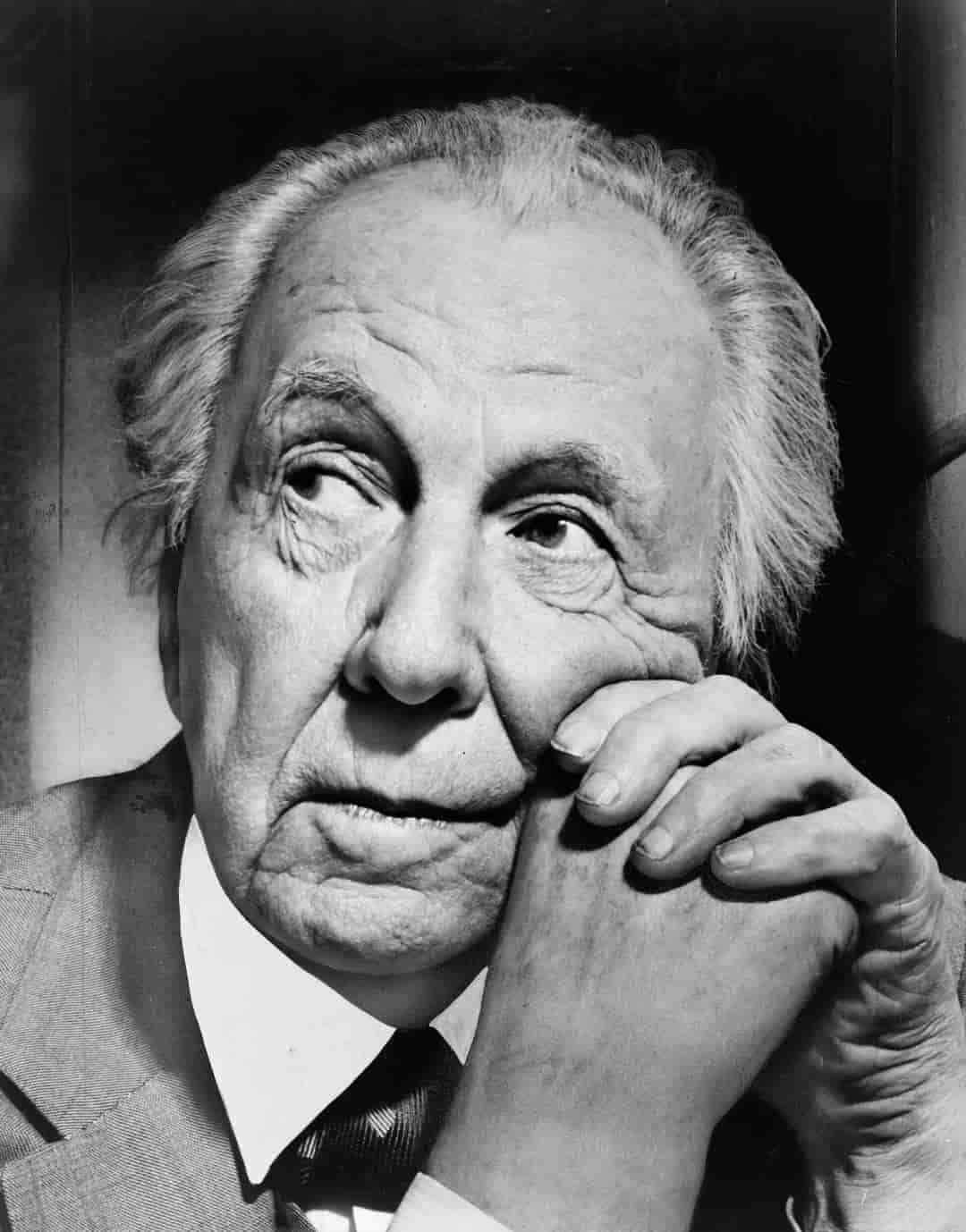

By the 1920s and 1930s, cinema had become a national obsession. Hollywood’s golden age produced timeless classics such as Gone With the Wind, and the star system was born. Film icons like Clark Gable and Gary Cooper became symbols of American glamour, admired and idolised by millions.

Music, too, defined the era — particularly the exuberant spirit of the 1920s. Known as the Roaring Twenties or the Swinging Twenties, the decade was marked by a dazzling joie de vivre that often bordered on excess.

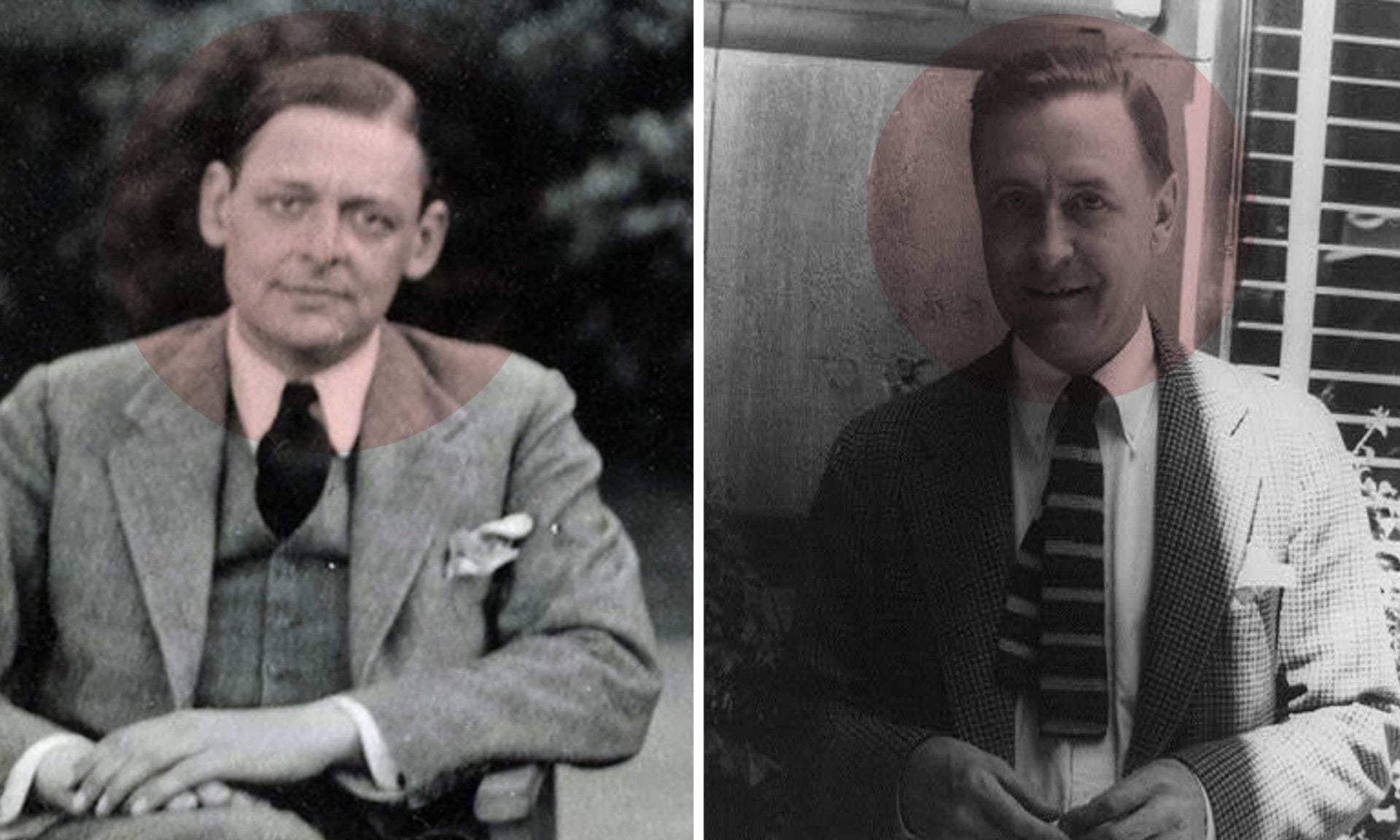

The Charleston was the dance of the moment, and nightclubs pulsed with jazz and energy. Parties were extravagant, and the culture of pleasure was captured brilliantly by F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby.

His short novel epitomised the glittering yet hollow pursuit of wealth and status that characterised the decade. T.S. Eliot praised the book, saying, “It has interested me and excited me more than any new novel I have seen, either English or American, for a number of years.”

This splendour, however, came to an abrupt end with the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The Great Depression that followed transformed the nation’s spirit: prosperity gave way to struggle, and survival replaced celebration. Relief programmes became the new focus of national life.

The advent of the Second World War soon shifted attention to global conflict. Americans united against a common enemy, channelling their energy and resources into the war effort against Japan and Germany.

The optimism and subsequent struggles of the pre-war years were replaced by determination, resilience and solidarity.

- In the next article we shall be surveying the historical and social background of the 20th century before eventually zooming into the vibrant literary innovations born from the creativity of 20th century American writers.

- Part 1: The making of American culture

- Part 2: The birth of American literature