It's barbaric and repulsive: Let's Axe the Death Penalty

Executing a human being is as coldblooded and premeditated as murder can get, writes Adrian Liberto

Put simply, the death penalty involves legally killing an alleged criminal. “Alleged”, not only because the person may not have committed the crime in the first place, but equally because the crime may have been labelled as such only due to the distorted perspective of the lawmakers. At times, this perspective is biassed in favour of jealousy, bigotry, the acquisition of wealth and power; or the neutralising of a rival or critic.

Only a few weeks ago, the junta in Myanmar did just that, by hanging four of its critics. History is full of such examples. In every age and every corner of the earth, people have been executed for simply saying the truth, expressing a belief or trying to stand up for their rights. Subversives, witches, sectarians, heretics… of course I am using the language of the enemy here. These were probably just enlightened or ordinary people whose death may simply have been of benefit to the powers that be. Sometimes even genocide was legal.

Death penalty in history and art

On the fresco of Santo Stefano Rotondo there are 34 large panels dating from 1572-1585. Commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII they depict realistic depictions of torture and suffering of the sufferings of the martyrs.

The unique and eerie church of Santo Stefano Rotondo in Rome offers an interesting representation of the death penalty with its 16th century frescos by Niccolò Circignani (Pomarancio) and Antonio Tempesta, commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII and portraying 34 scenes of martyrdom.

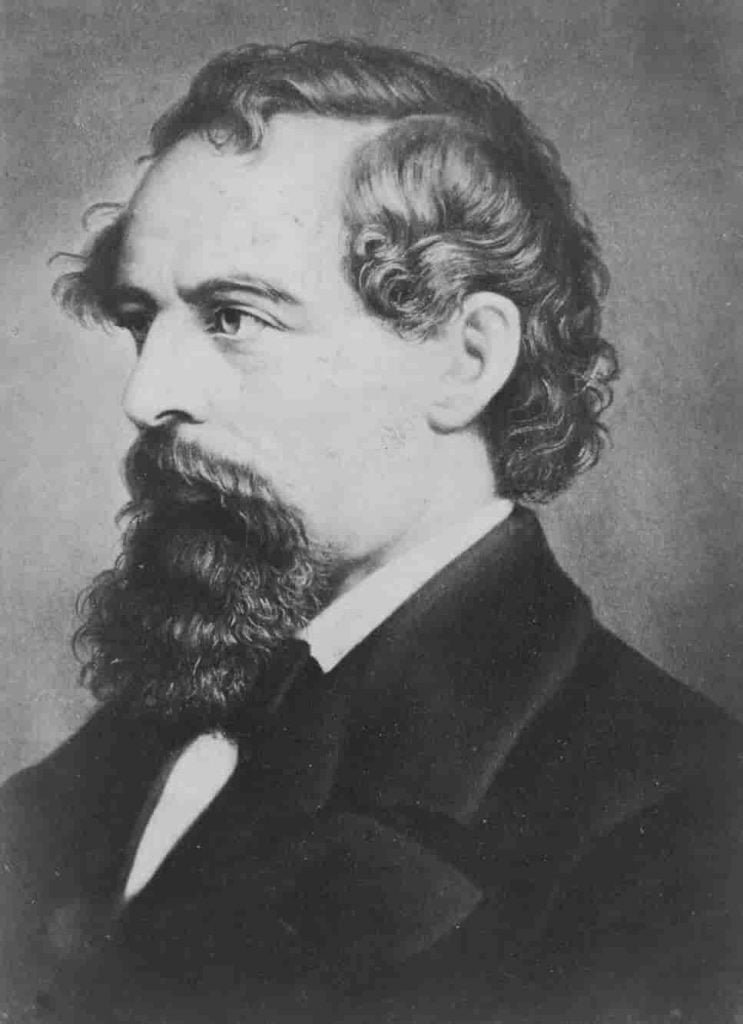

To say that they are gruesome would be an understatement, but Charles Dickens does a good job in describing them in his Pictures from Italy:

Charles Dickens © Public Domain

“To single out details from the great dream of Roman Churches, would be the wildest occupation in the world. But St. Stefano Rotondo, a damp, mildewed vault of an old church in the outskirts of Rome, will always struggle uppermost in my mind, by reason of the hideous paintings with which its walls are covered. These represent the martyrdoms of saints and early Christians; and such a panorama of horror and butchery no man could imagine in his sleep, though he were to eat a whole pig raw, for supper. Grey-bearded men being boiled, fried, grilled, crimped, singed, eaten by wild beasts, worried by dogs, buried alive, torn asunder by horses, chopped up small with hatchets: women having their breasts torn with iron pinchers, their tongues cut out, their ears screwed off, their jaws broken, their bodies stretched upon the rack, or skinned upon the stake, or crackled up and melted in the fire: these are among the mildest subjects.”

I suppose we can now add the electric chair and the lethal injection to the mix. Still, my concern in this article is not so much the means, as the principle itself. Nor will I delve into its use by backward governments that apply it for bigoted or despotic reasons such as sodomy, adultery, atheism or, as in the case cited above of Myanmar, oppression.

Anyone with a shred of decency would know that such abuse of power is barbaric and repulsive. I will therefore focus on three points:

- I will discuss whether it is an effective deterrent;

- I will consider whether it is predominantly safe from error or abuse and finally;

- I will focus on whether it is morally acceptable even in the clearest cut case of a murder having been committed.

Spicing death up: Is the death penalty an effective deterrent?

Thankfully, nowadays many countries have abolished the death penalty. By the end of 2021, 108 had done so. They realised how open to abuse or miscalculation such a practice could be, but more importantly, the futility and injustice of the principle itself. Of course, the US is not in that category, with over half of its States allowing the death penalty.

A lethal injection room in Florida State Prison. Over half of the States in the United States allow the death penalty. ©Public domain

In 2021, the US had executed 11 people. Needless to say, it is not in very good company, as far as human rights go, with China topping the list of executions, followed by Iran, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Syria. According to Amnesty International:

“At the end of 2021, at least 28,670 people were known to be under sentence of death. Nine countries held 82% of the known totals: Iraq (8,000+), Pakistan (3,800+), Nigeria (3,036+), USA (2,382), Bangladesh (1,800+), Malaysia (1,359), Viet Nam (1,200+), Algeria (1,000+), Sri Lanka (1,000+).”

Clearly, these countries think that the death penalty is a deterrent and, in some instances, they may be right, but only if terror is added to the mix. Many people have a fatalistic view of death, or at least they have come to terms with it. Death of itself is not much of a threat when we are angry or motivated enough to want to kill someone. However, as the ancients understood, and the Santo Stefano Rotondo frescos highlight, by adding agony and torment to the equation, people are more likely to think twice.

As soon as the Christians moved from the arenas to the stalls, they too adopted the oppressive practices, burning people at the stake being one of their favourites, although by the 1800s the Papal States tended to opt for hanging, beheading and bludgeoning to death instead. Different cultures had different methods.

One of the most gruesome was certainly a Persian method known as scaphism, or the boats. This involved locking the unlucky victim within two boats after having over fed or force fed them so that their excrement could attract all kinds of insects, while the face arms and legs, which were left popping out, were covered in milk and honey to attract other insects. It was an extremely slow and excruciating death.

Building a whole culture around fear could therefore work as a boost to the death penalty in keeping people in check especially when the death penalty or severe sentences are imposed for harmless deeds or minor crimes because the spectre is forever hanging over one’s life. Despotic states like Iran function that way, but so did European countries, until fairly recently.

In England, for instance, the last people to be hanged for sodomy were James Pratt (1805–1835) and John Smith (1795–1835): they were convicted simply by the testimony of a landlord peeping through a keyhole.

Statistics indicate the truth about death penalty…

Remove the overall oppression and the horror, however, and statistics indicate that the death penalty is not really an effective means of keeping people from committing serious crimes like homicide. In the US, for instance, the statistics show that States that did not have the death penalty, had consistently fewer murders than those that did, with the gap widening consistently since the 1990s. So yes, when linked to barbarism and oppression, the death penalty can be a deterrent, but otherwise it is not. This is probably also because States that do not opt for the death penalty, such as Finland, invest more in prevention and education, and setting the example of valuing all human life.

Doubting all reasonable doubt: Is the death penalty safe from error or abuse?

According to data collated by Science, in the US, up to one in 25 people who are sentenced to death may actually have been erroneously convicted. The Equal Justice Initiative found that for every nine people executed in the US, one person on death row gets exonerated.

Sometimes these are bona fide convictions that just got it wrong… often they are not. The deceit and abuse involved in some of these cases is mind boggling, especially when prejudice is involved, as in the conviction of Walter McMillian (Johnny D.), a black man from Alabama.

He was accused of having murdered an 18-year-old white woman in 1986. Despite multiple witnesses confirming his alibi, he was convicted in 1988 after a trial that lasted only one and a half days. The predominantly white jury chose to ignore the overwhelming evidence in his favour and relied solely on the word of three witnesses who had testified against him.

The Alabama Judicial Building. Photo: J. Stephen Conn/Flickr

The sentencing verdict was life, but the judge, Robert E. Lee Key, overruled it and pronounced the death sentence instead. Johnny D. did not have a criminal record and was a respected self-employed logger. However, he was known to have had an affair with a white woman, which was enough to mark him as a target for enquiry by a racist institution that was struggling to find a lead. After about six years on death row, he was finally released in 1993, when irrefutable evidence, including a tape recording, proved that the witnesses had been coerced to falsely testify against him. The Equal Justice Initiative puts it plainly:

“Our death penalty system treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent. As a result, a stunning number of innocent people have been sentenced to death.”

Of course, not every convicted person can be as “lucky” as Johnny D. (if we can call someone who had to undergo six years of hell, lucky); many are forced to take their innocence to their graves.

Notable miscarriages of justice in the US include: Carlos DeLuna (convicted in 1983 and executed 1989) Ruben Cantu (convicted in 1985 and executed 1993) and Larry Griffin (convicted in 1981 and executed 1995).

So when it comes to the death penalty, we are left with a paradox: only a perfect system could ensure that errors in conviction are not made, but if such a system existed, it would certainly be rehabilitative rather than vindictive. In other words, by its mere existence, the death penalty excludes the possibility of a safe, evolved and fair justice system.

A life for a deed: Is the death penalty morally acceptable even in the clearest cut case?

The walls of the Santo Stefano Rotondo church portray 34 scenes of torture. Photo: ho visto nina volare/Flickr © Creative Commons

For better or for worse, things change. The church of Santo Stefano Rotondo changed for the worse when a recent renovation repaved the floor with glaring glossy tiles that would have been more at home in a fast-food restaurant than a church whose roots go back to Emperor Constantine himself.

People also change, unless they are killed, that is, and deprived of that chance, which is often what the death penalty does. “Often”, because sometimes it does give that chance: people are kept on death row for years, allowed to change, usually for the better, and then killed off irrespective.

A mugshot of Karla Faye Tucker

The case of Karla Faye Tucker is a perfect example of this. She committed a double murder in 1983 when she was 23 and in a bad place as she explained in touching interview to Larry King:

“A lot of drugs, a lot of anger and confusion, no real guidance, I was just out of hand, and had no guidance at a certain point in my life when I was most impressionable and probably could have been steered the right way. There wasn’t anybody there to steer me.”

Tucker was arrested a few weeks after her crime and sentenced to death late in 1984. She was held on death row until 1998 when she became the first woman to be executed in Texas since the Civil War. Within that time, she had become a born-again Christian and a completely reformed person, even marrying her prison minister, Reverend Dana Lane Brown, in 1995.

Revenge is better than redemption

There were, of course, many pleas for clemency, but these were rejected, right up to the 11th-hour appeal to block her execution made to George W. Bush, who was then the Texas Governor. In the minds of many legislators, revenge is better than redemption.

Spending agonising years in prison only to be executed years later is not uncommon in the US. Carey Dean Moore, for instance, who was sentenced to death in 1980 for the murders of two cab drivers, spent a whopping 38 years on death row before his execution in 2018. This is not justice, but abuse of power, plain and simple.

Coldblooded premeditated murder

St Augustine justified executions carried out according to the law, even though the law just over a hundred years earlier was condemning Christians to those gruesome deaths recorded on the walls of Santo Stefano Rotondo. He also exonerated the executioners:

“The agent who executes the killing does not commit homicide; he is an instrument as is the sword with which he cuts.”

Shaggy’s song It Wasn’t Me, springs to mind. Augustine’s are soothing words for an easily duped conscience.

The minute we allow ourselves to become “instruments” we have lost our humanity and are dangerous tools in the hands of any power that we would let ourselves be manipulated by, be it secular or religious. All said and done, executing a human being is as coldblooded and premeditated as a murder can get. It is not self-defence, because the danger has passed. It is not justice, because a person can always outweigh their deeds, and they can change, given the chance.

Taking that chance away is the true crime.